Читать книгу Living by Stories - Harry Robinson - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

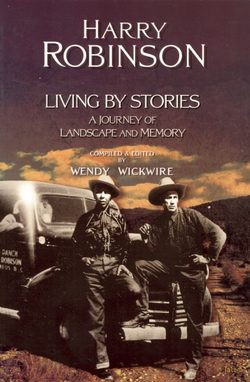

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Harry Robinson lured me into Coyote’s world. It happened on a baking hot day in mid-August 1977, during the initial leg of a week-long road trip through southern British Columbia. I was with three friends.1 Our first stop was Harry’s place just east of Hedley. As we pulled into his driveway, a series of stark contrasts came into view: in the distance, the mellow Similkameen River flowing through the dry valley dotted with sagebrush and ancient sunscorched formations of volcanic rock; in the foreground, the frantic Highway 3, lined with heavy transport trucks and cars winging their way to points east and west. These contrasts became more apparent in Harry’s front room where a large floor-to-ceiling picture window framed the details in glass.

Except for the hum of traffic, it was a tranquil scene. Harry’s tiny, 1950s bungalow was one of only two houses for quite a distance. And, other than a few cats, his “boys,” he was on his own. He was surprisingly agile, energetic, and independent for a man of seventy-seven. And he clearly enjoyed having visitors: he had prepared extra beds, anticipating that we would spend the night at his place.

When we had gathered around the Arborite table in his front room, one of us asked why there were no salmon in the local section of the Similkameen River. “That’s a long long story,” Harry explained. “It’s all Coyote’s fault.” Suddenly it was as if Coyote was right there. Harry’s easygoing demeanour changed. He stiffened, cleared his throat, and began telling us about Coyote’s antics along the local rivers, peddling salmon in exchange for wives. All went well, Harry explained, until he encountered the Similkameen people who rejected his offers. Miffed, Coyote drove the salmon permanently out of the lower reaches of the river by creating an impassable barrier.

Except for the occasional cigarette break, Harry told this story without interruption or props beyond a continuous series of striking hand gestures that were choreographed to the narrative. As the blazing sky cooled into dusk while the earth continued to radiate the day’s heat, the story consumed the evening. We sat transfixed, enjoying the travel back in time—who knows how far—to when the world was young and the landscape was first being formed and peopled. Harry broke from the storyline to point out tangible remains of Coyote’s trip along the river, such as his pithouse near the present-day town of Princeton.

By the end of the evening, I was hooked on what felt like a direct encounter with Coyote—a living Coyote linked to Harry by generations of storytellers. Harry portrayed him as a bit of a pest. As he put it, “Coyote was a bad bad boy!” But I figured he could not have been all bad because Harry laughed endearingly while telling us of his “bad” doings. I wondered about common English terms for Coyote: trickster, transformer, vagabond, imitator, prankster, first creator, seducer, fool. A generation of established writers such as Paul Radin, Gary Snyder, Barry Lopez, and others had used these;2 and yet Harry had not used a single one of them.

As we said our farewells late the next day, Harry invited us all to return. I assured him that I would. And I promised myself to first survey the ethnographies and oral narrative collections for this region to see how Harry’s forebears had depicted Coyote. A number of anthropologists—James Teit, Leslie Spier, Charles Hill-Tout, Walter Cline, Rachel Commons, May Mandelbaum, Richard Post, and L. V. W. Walters—had travelled through the Okanagan region between 1888 and 1933 collecting stories.3 So too had the Okanagan novelist Christine Quintasket (Mourning Dove) recorded traditional stories among her relatives and friends.4 Franz Boas and Teit had also published several collections of stories of neighbouring Salishan-speaking peoples.5

I was pleased to discover numerous fragments of Harry’s Coyote story scattered throughout the early collections. But the extensive variations among them made it impossible to find anything close to a single storyline. It was clear that Harry’s predecessors had held conflicting views about Coyote’s travels along the Similkameen. I skimmed the hundreds of Coyote stories featured in these collections: “Coyote Juggles His Eyes,” “Coyote Fights Some Monsters,” “Coyote, His Four Sons, and the Grizzly Bear,” “Coyote Steals Fire,” “Coyote and the Woodpeckers,” “Coyote and the Flood,” and so on. At the end of this survey, I did not feel particularly enlightened. In fact, Coyote seemed more contradictory and elusive than ever.

The print versions of these stories were short—on average, a page or two in length—and lifeless. Most lacked the detail, dialogue, and colour of Harry’s story. Many were also missing some vital segments. Coyote’s sexual exploits along the Similkameen River had been excised from the main text of an 1898 collection, translated into Latin and then transferred to endnotes.6 Such editing seriously disrupted the integrity of the original narrative. Names of individual storytellers and their community affiliations were also missing, thus making it difficult to assess the roles of gender, geographical location, or individual artistry in shaping the stories. In many cases, collectors had created composite stories from multiple versions, which erased all sense of variation in the local storytelling traditions.

Despite these problems, merely surveying the published sources prepared me for my next session with Harry—or so I thought until I turned up at Harry’s house exactly two years later. I was with Nellie Guitterrez, a Douglas Lake elder who was also an old friend Harry had not seen in years. He was delighted to see us. I was relieved that he remembered me. At the end of this visit, I arranged to return the following week on my own.

During the latter visit, I brought up one of my favourite topics—James (Jimmy) Teit, a Shetlander based at Spences Bridge on the Thompson River. I wondered if Harry had met Teit before the latter’s death in 1922. Teit had worked with New York-based anthropologist Franz Boas between 1894 and 1922. He had also served Aboriginal chiefs throughout the province in their campaign to resolve their land problems with European and American newcomers. I obviously struck a nerve because Harry began reconstructing the days of the “big meetings” (as he called them) attended by Teit at the behest of these chiefs. “Nowadays they call it the Land Question. Still going, you know.” There was a problem with these “big meetings,” he explained. Everyone had ignored how “Indians” had come “to be here in the first place”:

The Indians, they don’t say,

they don’t say how come for the Indians

to be here first before the white.

See?

They never did tell that.…

They never say how come for the Indians

to belong to that what they have claimed…

How come the Indians to own this place

and how come to be here in the first place?

Underlying this statement was the implication that the Indians belonged to the land, not vice versa, and that no justification was needed for their presence.7 Harry insisted that current disputes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples over land were flawed because people continued to avoid the issue of how these lands had been originally assigned. The answers, he explained, were contained in a story.

In a now familiar pattern, Harry sat upright, cleared his throat, and began telling the story. Once again Coyote loomed large. But much to my surprise, so did my first ancestor. The story featured a pair of twins charged to undertake a series of important tasks related to the creation of the earth and its first inhabitants. The elder twin performed his duties exactly as instructed, but the younger twin stole a written document—a “paper”—he had been warned not to touch. When confronted about his actions, he denied having done this. Because of this, he was immediately banished to a distant land across a large body of water. The elder twin was left in his place of origin.

The younger twin, Harry explained, was the original ancestor of white people; the elder twin was Coyote—“the Indians’ forefather.” “That’s how come,” Harry explained, “the Indians [were] here first before the white.” He then stressed that “that’s why the white man can tell a lie more than the Indian.… ” Part of the deal struck with the younger twin (my first ancestor) at the time of his banishment was that his descendants would one day travel to the home of the elder twin’s descendants to reveal the contents of the written document.

Time passed and all proceeded according to plan. The descendants of the elder twin multiplied and populated the North American continent while the descendants of the younger twin did the same in their designated homeland across the ocean. Eventually, after many years, the latter made their way to North America. But, things went badly astray when, true to their original character, the descendants of the younger twin began killing descendants of the elder twin and stealing their lands. They also concealed the contents of the “paper.” When the conflicts between the two groups escalated, Coyote travelled to England to discuss ways of resolving these problems with the king of the younger twin’s descendants. Harry recalled a segment of Coyote’s speech to the king:

Your children is coming.

Lots of them.

They come halfways already from the coast to the coast.

And they don’t do right to my children.

Seems to me they’re going to run over them.

And they don’t care much for them.

Now we’re going to straighten that up.

And we’re going to make a law.

And the law that we’re going to make

is going to be the law from the time we finish.

Together Coyote and the king produced a book that outlined a set of codes by which the two groups were supposed to live and interact. “When they finish that law,” Harry explained, they call it the “Black and White” because “one of them was black and the other was white.” They made four copies, three of which they agreed to distribute to the descendants of both groups.

Harry’s sources for this story were able to trace the movement of the “Black and White” from England to various points in Canada. One man, TOH-ma, told Harry in 1917 that he had travelled with a man who was charged with delivering a copy of the “Black and White” to the legislature in Victoria. Another of Harry’s acquaintances, Edward Bent, had gained access to the book. Having attended residential school, he could read English. But he died before he could reveal its contents to his colleagues.

By now I was very confused. This Coyote story had so little in common with the quaint and timeless mythological accounts in the published collections. I wondered about the references to my first ancestor. I had not encountered anything like this among the published accounts for this region. The Coyote at the centre of this story was not portrayed as the trickster/seducer/pest that he had been in the story Harry had recounted for us two years earlier. Rather, this original ancestor of the “Indians” was the obedient twin who dutifully followed the orders of his superior. In this story he represented goodness. My first ancestor, by way of contrast, represented the opposite: he was a liar and a thief. Even more surprising was Coyote’s ability to travel freely between prehistorical and historical time zones as revealed in the segment of the story about the meeting between Coyote and the king. Such movement was uncommon in the early collections.

Because I had encountered so few references to whites and other postcontact details among the published “myths/legends” I had surveyed, I bracketed this story as an anomaly. The theoretical literature on the subject supported this move. For example, Claude Lévi-Strauss’s The Savage Mind, one of the leading sources on myth at the time, had divided “myths/legends” into two separate zones—“cold” and “hot”—depending on their cultures of origin.8 “Cold” zones were associated with Indigenous peoples with a mythic consciousness that tended to resist change; “hot” zones, on the other hand, were associated with Western peoples with a historical consciousness that thrived on constant, irreversible change. As Harry was immersed in a cultural zone which Lévi-Strauss would have classified as “cold,” it followed that his corresponding narrative repertoire should be predominantly timeless and ahistorical.

But Harry’s stories did not fit this pattern. Immediately after recounting his story about Coyote’s origins and his meeting with the king of England, he proceeded to tell a series of four narratives situated squarely in the early twentieth century. Analyzed according to the Lévi-Straussian model, therefore, his repertoire was more “hot” than “cold.” There was certainly nothing timeless about it.

Harry told the four historical narratives to illustrate the importance of the special power given to “Indians” via Coyote at the beginning of time. The first was about Susan Joseph, an Okanagan woman who had used this power to “doctor” a seriously injured man. The other three were about various individuals who had used it to cure themselves during times of crisis. Harry stressed that this power was intimately connected to the natural world:

You got to, the kids, you know,

they got to meet the animal, you know, when they was little.

Can be anytime ’til it’s five years old to ten years old.

He’s supposed to meet animal or bird, or anything, you know.

And this animal, whoever they meet, got to talk to ’em

and tell ’em what they should do.

Later on, not right away.

I wondered why I had not encountered any such historical narratives among the early published collections that I had surveyed.

By September 1980, I was back again in Hedley. At Harry’s urging I began to extend my visits. If I wanted to hear stories, he explained, I had to stay for more than just an afternoon:

There’s a lot of people come here just like you do.

Some of them stay here two, three hours only.

Well, I can’t tell them nothing in two, three hours.

Very little.

But some people, one man, we talk, I and he, for over twelve hours.

So they really come to know something of me.

It takes a long time. I can’t tell stories in a little while.

Sometimes I might tell one stories and I might go too far in the one side like.

Then I have to come back and go on the one side from the same way,

but on the one side, like.

Kinda forget, you know. And it takes time….

He also warned me that if I were truly serious about his stories, I should not waste time: “I’m going to disappear and there’ll be no more telling stories.”

He was right about the value of longer visits. In addition to making time for more storytelling, extended visits enabled us to spend afternoons doing other things such as meandering through backroads at leisure, visiting people here and there, and running errands which served to prompt further memories and stories.

As always, Harry surprised me with his stories. He opened our first evening session in September 1980 with a long story about white newcomers. After establishing the story’s setting at the junction of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers, Harry noted that it was a very old story that had taken place “shortly after when it’s become real person instead of animal people” but before the arrival of whites. The focus was a young boy and his grandmother who had been abandoned by the rest of their community because of the boy’s laziness. One day they were visited by an old man whom they invited to share a meal. This man taught them new and more effective methods of hunting and fishing in return for the gift of a patchwork blanket composed of the feathered hides of bluejays and magpies, which was all the boy and his grandmother had to offer.

Before departing, the visitor revealed that he was “God” in disguise and that one of his reasons for visiting them was to convey that “white-skinned” people would arrive someday to “live here for all time.” He explained in detail how these newcomers would give the land a patchwork appearance with their “hayfields” and “gardens.” But they would never take ownership of the land because “this island supposed to be for the Indians.” God told the boy and the woman, “This is your place.” As a testament to this statement, God placed the patchwork blanket on the ground, whereupon it transformed into stone. Harry explained that one of his lifelong goals was to travel to Lytton to find this important stone which had been concealed by an earlier generation to prevent discovery and possible theft by whites.

As with the earlier story about the twins, I decided to bracket this account. Although I had found numerous variants of the story among the old sources, the latter included no references to God or whites. Instead, the central figure was “Sun” or “Sun man” who gave the boy and his grandmother things like bows, arrows, and cooler weather.

I continued to visit Harry regularly throughout the rest of the fall. And Harry continued telling stories. After recounting the story about God’s visit with the boy and his grandmother, he initiated a long cycle of Coyote stories. Again, God turned up in these stories. Having overseen the creation of the world and its first people, this “God” was always lingering in the background of the stories. Although Harry often referred to him as “God,” he occasionally called him by other names. For example, in his story about how Coyote got his name, Harry used the term “Chief”: “that supposed to be the Creator, or the Indians call him the Big Chief. Could be God in another way.”

Harry’s point was that this “Chief” had also endowed Coyote with both a name (“Shin-KLEEP”) and special powers:

I can give you power

and you can have power from me.

Then you can go all over the place.

You can walk everywhere….

And there’s a lot of danger,

a lot of bad animal and monster in the country

and I want you to get rid of that.

One of the stories was about Fox, who could revive Coyote from death. While some of the stories focussed on Coyote’s good deeds, for example, his elimination of vicious cannibalistic monsters—spatla—who preyed on people, others highlighted Coyote’s “prankster/seducer” tendencies, for example, his plot to snatch his daughter-in-law by enticing his son to climb to a world in the sky, thereby exiling him to another level of existence. His son eventually returned and sent his lecherous father running. Coyote had few restraints on his power until he encountered God (in disguise) whom he challenged to a duel. Annoyed by Coyote’s hubris, God banished him to a remote place. “Just like he put him in jail,” Harry noted. Harry ended his Coyote series with an expanded version of his story about Coyote’s visit with the king of England. Except for the last story, all of these Coyote stories were firmly rooted in the deep prehistorical past—the time of the “animal people.” (Harry called these “imbellable” stories. When I asked what he meant by “imbellable,” he explained that when he asked for the English word for chap-TEEK-whl—the Okanagan term for stories from “way back” during the time of the animal people—someone had given him the word “unbelievable.” Harry heard this as “imbellable” and applied it to his chap-TEEK-whl thereafter.)

At last I could see some tangible parallels between these stories and those that I had surveyed in the published records. However, just as I began to relax in this timeless zone of relative familiarity, Harry suddenly shifted back to the historical period. He told eight stories about recent human encounters with power. I wondered if he intended these to illustrate contemporary manifestations of Coyote’s powers—they appeared to me as having much in common.

The first of these historical narratives was about foreknowledge. Just as God had forewarned a boy and an old woman about the transformation of the landscape by white agriculturalists, a man in the 1920s had forewarned his people about the alteration of the landscape by multiple highways. Another story was about powerful transformations in contemporary times. Just as Coyote transformed monsters such as Owl Woman to stone, so a group of Indian doctors, disturbed by the intrusion of the first trains through Sicamous, used their power to stop the train in its tracks. Just as Coyote and his colleagues had been endowed with special relationships with animals, so their descendants shared a similar relationship as revealed in the stories about hunters saved from death by wolverines and grizzly bears. Just as God had introduced the boy and his grandmother to easier means of procuring food, so a couple of cranes provided two hunters with similar skills. Just as Coyote could transform himself into whatever he wished, so could a man called “Lefty,” who transformed himself into a wolf, a grizzly bear, and a frog to track a group of people who had abducted his sister. Just as there were monsters roaming around in Coyote’s time, so too were monsters roaming through the landscape in more recent times, as evidenced in the story about a squirrel that turned himself into a “gorilla” and then picked up a boy and carried him on his shoulders from Hedley to Yakima.

By late 1980, Harry and I had established a lively written correspondence to fill in the gaps between our visits. Having been taught by a friend to read and write English, he enjoyed writing letters. Although the process of writing was always slow (it took several days and many jars of correction fluid to produce a short letter), Harry derived great satisfaction from it. He carefully filed all of his incoming letters so that he could re-read and savour them. In turn, I enjoyed receiving letters from Harry. “Oh say,” he wrote on 7 February 1981, “I was going to tell you. I was verry Happy to hear from you. Last month you got here on 8th of January. When you left Im kind missin you Im still missin you tell I get a words from you that is why I was Happy than I get to started and writing letter.” Once, he offered advice that showed his appreciation of good penmanship and a well-turned phrase. He advised me to write clearly so that he could decipher every word: “You write it so fast. Is not clear. Should do like I did clear to every shingle letter and clear. Can be much better. Better for me to read” (7 February 1981). Sometimes his letters were long: “I could not Help it for written a long letter,” he wrote at one point, “because Im storyteller I always have Planty to say” (n.d.).

Harry included many personal reflections in his letters: “I can never forget for long time the good time we have when we together. Hope its going to be some more good times for you and I” (1 March 1981). Sometimes he advised me on issues of cultural protocol. Until around this time, I had been paying Harry standard consulting fees. In his letter of 7 February 1981, however, he suggested that I stop doing this. He was obviously uncomfortable with being “paid” for sharing stories: “Im willing to tell you a stories at any time. You don’t have to pay me. If you happened to be around I might need your help or may not. Just depends.” Likewise, I much preferred this new arrangement that enabled me to run errands with him in lieu of dealing in cash.

The winter of 1981 was a highpoint in our relationship as I had rented a cabin in the Coldwater Valley, south of Merritt, for the year. With only an hour and a half’s drive from there to Hedley, we were able to get together regularly. In addition to visits at Hedley, Harry and I spent time at my Coldwater cabin. It was a busy year with lots of trips to see all his old friends throughout Nicola Valley, the Fraser Canyon, and Douglas Lake. In January and February, we travelled through northern Washington to take part in winter dances.

During this period, Harry opened my eyes to yet another new line of stories: historical narratives but with a strange twist. Each featured an extraordinary encounter with a lake monster, a devil, a strange snake, a talking cat, or another such being. According to folklore scholar Stith Thompson, such stories were common. And yet, they were rare in the published collections for British Columbia. I wondered if collectors, in their search for “authentic” mythological accounts, had glossed over such accounts because they were too Westernized.9

A number of these stories focussed on strange occurrences in and around lakes. For example, there were several stories about Palmer Lake. One involved a monster that swallowed a horse and released it a year later; another was about a herd of cattle that emerged from and then disappeared into the lake; and a third was about a man and his canoe swallowed by the lake. Okanagan Lake was the setting for a story about two men who disappeared mysteriously. And Omak Lake was the site of a number of strange happenings. One involved a blind calf that walked into the lake and never returned.

Other stories featured talking cats that could change at will into other forms. Some of these cats duped and killed nasty monsters or people who had insulted them. Others came to the rescue of those in need. For example, in one story, a cat used his power to endow a local man, Sammy, with cash. In another, a spotted cat warned a man against committing suicide. In still another, a cat took revenge on a woman who hated cats and treated them badly.

On concluding this series of stories, Harry took another sharp turn by recounting what he called “murder stories.” Many of these were set in the nineteenth century: for example, the story of a woman named Madeleine, who murdered a white man who attacked her while she was travelling alone on the trail. Harry had been in touch with Madeleine until her death at ninety in 1918. Another featured a man named Joseph of Chopaka, who in the mid-1800s killed a white man suspected of surveying lands for whites. Another story involved a man named “Polutkin,” who in 1845 was ordered by a chief to retrieve his wife who had deserted him for another man. There was also a story of Alexander Chilahitsa who took revenge on a man who had killed his wife while she was alone at their ranch; and another about Narcisse Tom Louis, who at the end of his life confessed to murdering a Chinese man. Few of these stories were straightforward accounts of conflict. For example, one story about George Jim, a local man who was captured, tried, and imprisoned in the 1880s, was more about the aftermath of a “murder” than the murder itself. According to Harry, Jim was abducted from the New Westminster Penitentiary midway through his sentence and taken to England where he served as an outlaw Indian in a sideshow. Harry also included numerous accounts of more recent “murders,” many of which were still well-known and controversial.

Then, during the winter of 1982, Harry retold his story about the creation of the world and the first people. On hearing it again, I began to question my earlier reaction to it. Harry obviously considered it important enough to be told a second time. And it was, after all, the story that he claimed was missing at the political meetings of his youth—that is, the story that explained “how come Indians to be here in the first place.” The story also explained why Indians and whites derived their power from two completely different sources. For Indians, power was located in their hearts and heads; for whites, it was located on paper. Harry elaborated again on the process required for Indians to gain power:

Long time ago, the Indians just like a school.

When they got to be bigger,

they send ’em out alone at night or even in the daytime.

And left ’em someplace.

Leave ’em there alone, by himself or herself.

It’s got to be alone.

The animal can come to him or her and talk to ’em.

And tell ’em what he’s going to do.

And that’s their power.

They give ’em a power and tell ’em what they’re going to do

what work they going to do….

This power, they call it shoo-MISH.

That’s his power.

That was the animal they talked to ’em.

Doesn’t matter what kind of animal.

Any animal—bear or grizzly or wolf or coyote or deer—

any animal can talk to ’em.

To illustrate this connection between the shoo-MISH and humans, Harry told another long series of stories. He began with the story of his wife, Matilda, who encountered a dead cow that gave her a song and told her, “You going to be a power women.” He then told the story of another woman, Lala, who encountered a dead deer with a similar message and accompanying song.

Harry’s story of Shash-AP-kin typified the stories in this cycle. Left alone at the age of ten or eleven by his father and a group of hunters, Shash-AP-kin began to play with a chipmunk. In an instant the chipmunk turned into a boy, who told him, “This stump … you think it’s a stump but it’s my grandfather. He’s very very old man…. He can talk to you [and] tell you what you going to be when you get to be middle-aged or more.” At that moment the boy turned into an old man who told him that he would give him power to withstand bullets. He then sang a song and the boy joined him in the singing. The boy then fell asleep. When he awoke, “he knows already what he’s going to be when he get to be a man.” Harry says that when the white people arrived, “they all bad, you know. They mean. They tough.” They shot Shash-AP-kin. But the latter was able to withstand their bullets by using this power he had received from the smooth stump. He lived to be an old man, Harry explained. “They never get him. They never kill him.”

This last set of stories marked the end of our relaxed and easygoing visits. During the spring, Harry’s health took a sharp downturn when a nagging leg ulcer required his hospitalization for six weeks in Penticton. It was a miserable time for Harry who had little faith in white doctors and their medicines at the best of times. Convinced that his ulcer had been caused by plak, a form of witchcraft, he believed that white doctors could not cure it. His view was that because a member of his community had triggered this ulcer problem in the first place, it would require an Indian doctor to heal it.

He found the hospital culture cold and alienating. Everything about it was antithetical to his ways—bedpans left standing in the washroom, windows locked in a closed position, enforced bedtimes, and so on. After six weeks, when he could stand it no longer, he checked himself out of the hospital on the grounds that it was “too dirty … [and] no good for an Indian like me” (letter, 12 September 1982).

At home, he grew worse by the day. As he wrote on 27 September 1982, “Im really in Bad shape.” As I was by then based in Vancouver, I urged him to consider a Vancouver-based Chinese herbalist. He was keen on this idea: “If I can only see that Chinese Doctor it don’t mather much about the cost. Is to get Better. That’s the mean thing” (letter, 27 September 1982). When the herbalist died partway through his treatments, Harry became thoroughly discouraged and depressed.

Throughout the next two years, he remained at home in Hedley where he tried to manage his ulcer on his own, supplemented by the occasional treatments by Indian doctors. He was happy to find a local Keremeos physician, a woman who was willing to work with his beliefs about the cultural source of his problems. I visited often, but our daily drill was very different from what it had been in earlier years. He now slept through most of the day and evening. Then he was awake and up all night, often moaning in pain. I made meals and drove him to his medical appointments. We resumed our storytelling sessions whenever he felt in the mood for them.

During a visit in mid-April 1984, Harry became so ill that he worried that his death was imminent: “Now I’m sure I’m not going to live any longer … I could have died last night … or maybe tonight. Never know.” Nevertheless, he propped himself up, cleared his throat, and told a cycle of four stories. Each one was about an individual who could predict his/her own death. Although telling these stories sapped his energy, he seemed determined to get through them. I perceived that he had a larger motive in mind.

At the end of this cycle Harry sank back into his pillow and announced that “you can still hear that when I dead.… And that way in all these stories. You can hear that again on this (points to the tape recorder) once or twice or more.” He continued,

And think and look

and try and look ahead and look around at the stories.

Then you can see the difference between the white and the Indian.

But if I tell you, you may not understand.

I try to tell you many times

But I know you didn’t got ’em.…

So hear these stories of the old times.

And think about it.

See what you can find something from that story.…

He stressed again that he feared that he was approaching the end of his storytelling, “I’m not going to last very long.”

So, take a listen to this (points to my recorder)

a few times and think about it—to these stories

and to what I tell you now.

Compare them.

See if you can see something more about it.

Kind of plain,

But it’s pretty hard to tell you for you to know right now.

Takes time.

Then you will see.

He then stated, “That’s all. No more stories. Do you understand?” Shocked and saddened, I replied, “Sort of.”

It was a relief to hear that Harry had expected me to listen to his stories many times before drawing any conclusions. He stressed that they contained hidden messages and connections that would take time to decipher. I reflected on how passionately he had told his stories about whites and how quickly I had dismissed these as anomalies. Harry’s comments suggested that he may have had more of a prior plan than I realized.

At this stage, however, there were more pressing concerns for all of us than analyzing the deeper meanings of his stories. Harry was growing weaker by the day. In desperation, he finally asked his neighbour, Carrie Allison, to call an ambulance. He was quickly admitted to the Princeton Hospital. After several months of treatment, he had improved enough to be discharged. But it was now clear to everyone that he was not well enough to live at home by himself. As he and Matilda had had no children, he was unable to draw on immediate family members for assistance. So he moved to Pine Acres Home, a seniors’ residence operated by the Westbank Indian Band.

Institutionalized living, however, did not agree with him. Many of the residents were suffering from dementia so he could not carry on conversations with them. And he missed the familiarity of the Similkameen Valley. After a year, he transferred to Mountainview Manor, a seniors’ complex located in the heart of Keremeos. He was happier there in a self-contained, ground-floor unit which felt more like home. His band also provided twenty-four hour home care which gave him a continuous sense of companionship and support. As with his earlier routine, he slept during most of the daytime hours and sat up all night. Worried about his digestive system, he ate almost nothing. I visited regularly and he continued to tell stories. But the old vigour and enthusiasm were diminishing.

There was one project during this period that kept his spirits high, however. In 1984 while he was living at Pine Acres Home, we began discussing the possibility of turning his stories into a book. He felt that the book should be widely disseminated throughout “all Province in Canada and United States, that is when it comes to be a Book” (letter, 27 January 1986). The project kept his mind occupied. And it also gave him a set of daily goals as he struggled to think of gaps. The best part was that it inspired him to tell more stories.

Many of these new stories focussed on his life history. He was very proud of his ranching experiences and wanted some of these to be included in the book: “I get to started feed stock from 2nd Jan. 1917 till 1972,” he wrote on 15 May 1985. “50 years I feed cattle without missed a day in feeding season rain or shine. snowing or Blazirt. Sunday’s. holirdays. funeral day. any other time … 50 winter’s that should worth to be on Book if is not too late.”

Harry explained that he was twelve years old when he got his first paying job. It was with a crew of workers hired to thresh wheat and oats at Ashnola. He recalled every detail of the experience—driving the horses, cleaning up the straw, pushing all the grain into place, and piling it into baskets. Unfortunately, he hated it so much that he quit after a couple of months to try another job—pitching hay for fifty cents a day. When he quit the second job after just a few months, his mother, Arcell, took him aside, and scolded him for his poor work habits. She must have made an impact because he recalled that he took his next jobs as ranch hands much more seriously. The first of these was with family friend, Indian Edward, who gave him his first horse as payment for his work. Under Edward’s tutelage, Harry quickly became a skilled horseman and cattle hand.

Harry spoke constantly of horses and their place in his early life. “Those days the horses was a big business because no tractor, no truck, no nothing but only team of horses. And saddle horse and wagon and buggy. Use the buggy to go to town, kinda fancy. Wagon, more like a tractor, trailer, something. Heavy work, hauling rails, hauling hay, hauling something heavy with the horses.” Among his most poignant memories was the 1930s government campaign to exterminate the wild herds that roamed through the Similkameen.

He obtained his first ranch in December 1924, through his marriage to Matilda Johnny, a widow. Together Harry and Matilda established a good working relationship—buying, selling, and trading cows and horses. They bought and sold property until they had four large ranches between Chopaka and Ashnola. At one point, Harry employed a large crew to assist with his sixty horses and 150 head of cattle.

After Matilda’s death in 1971, Harry cut his ranching operation back to fifty head of cattle. A nagging hip injury forced him to retire completely two years later. He sold all of his ranches and rented a bungalow owned by his longtime friends, Carrie and Slim Allison. The hip injury turned out to be a good thing for his storytelling. Although he had spent lots of time listening to his grandmother and her contemporaries tell stories, he did not begin to tell stories until he was immobilized by the injury. While running his ranches, he simply had no time to sit for hours telling stories. “When I get older,” he explained, “and nothing I can do but tell stories.” He explained that the stories all came back to him much like “pictures” going by.

Many of these dated back to his early childhood when he was left for long periods to assist his blind grandmother, Louise Newhmkin. Among the stories of her family history was a special one about her aunt from Brewster, Washington, who married a prominent white man, John P. Curr. Harry’s grandmother adored this uncle whom she described as a highly respected “government man.” Curr had lived with the Okanagan Indians for five years until his Okanagan wife died. Louise passed on many of Curr’s stories to Harry. One of the most heart-rending stories chronicled the vigilante style murder of a prominent Similkameen chief by two members of Curr’s brigade in the 1830s.10

By now I had assembled a representative sample of stories for the book. I had hoped that Harry would assist with this, but he declined: “That’s really up to you,” he wrote in a letter of 27 January 1986. “Don’t have to ask me about it. I wrote the some of it or I mention on tape and you do the rest of the work. The stories is worked by Both of us you and I.” I included Harry’s story about the creation of the world and the twins as well as his account of God’s visit to Lytton. Along with a selection of Coyote stories, I included a number of stories about early and more recent human encounters with their shoo-MISH. I concluded the volume with a selection of historical narratives dealing with Aboriginal interactions with whites. Unfortunately the publication process took more time than we expected. By 1987, Harry was worried that he might not live to see the release of the book: “Im in Hospital but I can’t write…. We might see that Book yet I hope. Its all moste 2 years since we got start about that Book. Please let me know all you have know about for that Book” (letter, 8 March 1987).

Write It on Your Heart: The Epic World of an Okanagan Storyteller was finally released in late October 1989.11 The timing was perfect. Harry was frail but able to study the book’s contents. He was also well enough to attend the book launch celebration on 13 November in Keremeos. From his wheelchair, he was feted by a crowd of approximately one hundred friends and relatives, some of whom had come from distant points in Washington State. In addition to signing books, he made speeches, sang, and played his drum. In return, the local drumming group performed in his honour. This was his last formal outing. Harry died just over two months later on 25 January 1990.

Harry was very pleased with the book. His only concern was that it had not included all of his stories. I explained that we had recorded too many stories for one single volume and that presenting his words in poetic form had also consumed extra space. With Harry’s concerns in mind, however, I moved quickly to assemble a second volume of stories. Entitled Nature Power: In the Spirit of an Okanagan Storyteller,12 it featured stories about human encounters with their shoo-MISH. Although I had not fully met Harry’s objective to have all of his stories in print, I nevertheless felt the two volumes gave a representative sense of the whole.

Over the next few years, however, I continued to reflect on the stories that I had left out of these two volumes—stories such as Coyote’s meeting with the king and others about talking cats and disappearing cows and horses. The latter were so unusual and so unlike anything in the Boasian collections that I had decided to put them aside. But then I began to wonder how much of Boas’s editorial decisions had influenced my own selection process.

My timing for such questioning was ideal. In the early 1990s the Boasian research paradigm had become the subject of intense critical scrutiny.13 The poststructuralist turn in the social sciences was partly responsible for this review. It had spawned a new generation of scholars intent on exposing the ideological foundations of anthropological practice. The Boasian project was an easy target. Critics such as James Clifford, Rosalind Morris, Michael Harkin, David Murray, and others focussed on a number of issues, in particular the Boasians’ fixation on the deep past. Although the Boasians had recorded hundreds of Aboriginal oral narratives, they had limited themselves to a single genre: the so-called “legends,” “folk-tales,” and “myths” set in prehistorical times. They had little interest in the fact that many of their narrators were horsepackers, miners, cannery workers, missionary assistants, and laborers who maintained equally vibrant stories about their more recent past. As Harkin explained, the collectors’ goal was to document “some overarching, static, ideal type of culture, detached from its pragmatic and socially positioned moorings among real people.” Thus they “systematically suppressed … all evidence of history and change.”14 Such erasure had serious long term consequences for Aboriginal peoples.

Anthropologists working in South America were pursuing a similar line of argument at this time.15 Their target was Claude Lévi-Strauss, who had used Amazonian examples to test his theories of “cold,” mythic societies. As Terence Turner explained, “To base one’s entire analysis of social consciousness … on one or a few traditional rituals and narratives and then to conclude that the culture as a whole is in the mythic phase, lacking a concept of history, may reflect a lack in the investigative procedure more than a lack in the culture.”16 Emilienne Ireland endorsed Turner with her study of “white man” stories of the Waura peoples of Brazil. She stressed that myth was important for its ability to “mak[e] statements about the present and the future.” The Waura “myth,” she explained, took “a historic tragedy of monstrous proportions and transformed it into an affirmation of their own moral values and of the destiny to survive as a people.”17 Charles Hill-Tout, a British ethnographer who worked among the Okanagan in 1911, was particularly entrenched in the salvage paradigm. His position on the “mythology” he collected was that it was valuable for revealing “the mind of the native as it was before contact with white influence.”18 “In no other way now,” he wrote, “can we get real and genuine glimpses of the forgotten past. They are our only reliable record.… ”19 Never mind that the “minds” in question were several generations removed from precontact times or that the tellers of the myths had not experienced life without whites.

The impact of this fixation on “myth” hit home one day when I was sifting through some fieldnotes sent to Franz Boas from British Columbia by his colleague, James Teit. Among the latter’s notes was a version of the story Harry had told me about God’s appearance at Lytton to trade his knowledge of whites for a patchwork blanket. According to Teit’s account the visitor was “Sun” who traded four items—a gun, a bow, an arrow, and a goat-hair robe—for the old woman’s “blankets of birds-skins.”20 Yet, when Boas edited the story for publication, he had removed the word “gun” from this list, thus transforming what may have been intended as a historical narrative into the more desirable “precontact” myth.21 Boas was familiar with the story as he had recorded a Nlaka’pamux version at Lytton in 1888.22 I was curious to see that just as Harry had told me that story during one of our first sessions, one of the Nlaka’pamux storytellers had similarly told it to Boas during his first session at Lytton.23

Such examples raised questions about the messages that collectors gleaned from their narrators’ stories. Could Boas have mistaken a contemporary— even quasi-Christianized—story for a traditional “myth/legend”? Could he have edited a historical account to make it fit his vision of a prehistorical myth? And what about the Nlaka’pamux storytellers? Could they have selected this story for Boas, as Harry did in my case, to convey a political message—that whites were, and would always be, visitors on “Indian” land? Could they have told it to establish their superiority in relation to whites, that is, that they had had knowledge about the arrival of whites before their actual arrival? Did their “Sun” have associations with Harry’s “God”? The Sun of the 1888 Lytton session was, after all, “a man” who lived in the sky above an “ocean” somewhere far to the east.

Determined to resolve some of these issues, I scoured the old collections hoping to find further references to guns, whites, and other such things. Although Boas was preoccupied with suppressing such “impurities,”24 I knew that one of his most active field associates, James Teit, was not. Teit was fully immersed in the contemporary lives and languages of Aboriginal peoples through his Nlaka’pamux wife, Antko, and his work as a translator for the Aboriginal political protest organizations.25 Through such cultural immersion, he was more aware than many of his colleagues of the full range of stories in their natural settings.

I quickly found a little-known Teit collection featuring seven stories literally peppered with cultural “impurities.”26 It was exactly what I needed. Even better, these were Similkameen stories. They were published as “Thompson Indian Tales,” but this was in fact an error. Teit’s fieldnotes had indicated clearly that some of the stories had originated with “Bert Allison,” a prominent Similkameen chief.27

The opening story was perfect. Entitled “Coyote and the Paper,” it featured an encounter between “Old One or Great Chief” and Coyote in which the former tried to replace Coyote’s excrement (from whom Coyote often sought counsel) with paper so that Coyote would have an easier time carrying it around. Coyote accepted the paper but then lost it a few days later. The narrator considered this a major loss. “If Coyote had not lost it [the paper],”he explained, “the Indians would now know writing, and the whites would not have had the opportunity to obtain written language.”28 In the context of this story, Harry’s accounts of the twins and the paper, and others about meetings between Coyote and the king were not so unusual after all.

There were references to whites scattered throughout this collection. Several stories featured groups of young men—brothers/companions—who travelled to “towns” in search for work: blacksmithing, carpentry, farmwork, cowboying, and splitting wood. Life was not easy as they had to deal with nasty employers and landowners who made impossible demands on them. For example, in one story, a boy named Jack encountered a man who so objected to his marriage to his daughter that he threatened to kill him if he could not clear a dense piece of forest in a single day, or if he could not make water flow instantly from a distant creek to his house.29

Several stories targeted white authority figures. In one account, a young man, Jack, was challenged by his employer to steal the priest from the next village. So he concocted a grand plan. He dressed himself up as a priest, went to the church in the next village, lit the candles, and began to perform mass. When the resident priest saw this, he knelt down and prayed. Jack told him that God had sent him to tell the priest that he was so pleased with his work that he wanted him to go to heaven without dying. All he had to do to get to “heaven tonight” was to climb into a sack and allow himself to be carried to a designated spot. The priest did as he was told. Jack then carried the sack to his uncle’s place. Once there, he told the priest that when he heard “the cock crowing, [he would] know that heaven is near, and [he would thus] be taken up soon after that.” When the people arrived the next day, they found the priest in the sack crying, “Let me be! The cocks have crowed and I will soon ascend to God.” On realizing that it was all a trick, the priest returned home.30

I could see many connections to Harry’s stories. But what interested me most about this collection was its 1937 publication date. Since this was fifteen years after Teit’s death, I deduced that these were stories that Boas had withheld from publication due to their “impurities.” He must have changed his mind toward the end of his career because he assigned Lucy Kramer to the task of editing the stories for publication in the Journal of Folklore.31

These little-known Okanagan stories provided a rich historical context for Harry’s stories. Finally there was tangible evidence that Harry’s forebears were not strictly “mythtellers” locked in their prehistorical past. I was now keen to look more closely at how Teit had handled the issue of individual variation in his earlier publications. His 1917 presentation of three Okanagan creation stories offered some valuable insights on this. Instead of following the usual pattern of turning the three stories into one composite story, Teit presented each story on its own.32 The end result was a set of three very different perspectives on how the world and its first peoples came into being. The first, entitled “Old One,” explained creation as follows:

Old-One, or Chief, made the earth out of a woman, and said she would be the mother of all the people…. Old-One, after transforming her, took some of her flesh and rolled it into balls, as people do with mud and clay. These he transformed into beings of the ancient world…. (80)

The second story, told by a Similkameen narrator, offered a different view:

The Chief above made the earth…. He created the animals. At last he made a man, who, however, was also a wolf. From this man’s tail he made a woman. These were the first people. They were called “Tai’en” by the old people, who knew the story well, and they were the ancestors of all the Indians. (84)

Later, “Old-One” made “Indians” in much the same way. He blew on them “and they became alive.” Teit noted that this story evolved into “the story of the Garden of Eden and the fall of man nearly in the same way as given in the Bible.”

The third story, entitled “Origin of the Earth and People,” had some obvious links to the first one, but it was still quite different from the other two:

The Chief (or God) made seven worlds, of which the earth is the central one. Maybe the first priests of white people told us this, but some of us believe it now.… Perhaps in the beginning the earth was a woman.… He transformed her into the earth we live on, and he made the first Indians out of her flesh (which is the soil). Thus the first Indians were made by him from balls of red earth or mud.… Other races were made from soil of different colours.… (84)

An Okanagan creation story published in 1938 by anthropologist Leslie Spier shed more light on the issue of individual variation. Collected by L. V. W. Walters, one of five students in Spier’s anthropological field school, the story was attributed to Suszen Timentwa, chief of the Kartar Band. Like Harry’s origin story, Timentwa’s story included references to whites, books, and laws. “[I]n the beginning as in the Bible,” explained Timentwa, “God created the world, and created animals.” This God gave Coyote a “little book” that he explained would “get you help to watch you from today.”33

Like Teit’s second account above, Timentwa included Adam and Eve in his story:

After Adam and Eve did wrong, God took away one land from the top and put it to one side for the Indians-to-be. God took the laws with the Indian land and left the other land without laws. Then God built an ocean to separate these lands: one land was for the Indians, another for the white people. Indians did not need books because they knew things in their minds that they learned from the creatures. About the time of Christ, God made the creatures. This was before Christ was born, so that Christ could preach about the other land.… When the white people came to the Indians here, the priest told the Indians what they had forgotten. (177)

It was difficult to determine a common storyline among these stories.

A survey of neighbouring Nlaka’pamux creation stories collected by Teit revealed a similar range of diversity. According to one, “Old One” took some soil from an upper world, formed it into a ball, and threw it into a lake. On hitting the surface of the water, it shattered and became “a broken mass of flats, hollows, hills and islets” much as we see now.34 According to another, Earth was a woman who lived with Stars, Moon, and Sun long before the world was formed. Because of her constant pestering, Sun abandoned her. Eventually, Stars and Moon did the same. “Old One” then took pity on her by transforming her into the present earth who gave birth to “people, who were very similar in form to ourselves.” But they knew nothing until “Old One” travelled around teaching them things.35

An elderly “shaman … from Sulus” told Teit that his grandfather had told him that “Old One” descended on a cloud from an upper world to a large lake. He pulled five hairs from his head and threw them onto the surface of the lake, at which point they became five “perfect” women who were endowed with “speech, sight, and hearing.” He asked each what they would like to be in life. The first said she would like to be “bad and foolish, and … seek after my own pleasure.” She claimed that her relatives would “fight, lie, steal, murder and commit adultery. They will be wicked.” The second wished to be good and virtuous and have children who would be “wise, peaceful, honest, truthful and chaste.” The third wanted to be the “earth” upon which her sisters lived. The fourth wanted to be “fire.” And the fifth wanted to be “water,” from which people drew “life and wisdom.” He then transformed them. The third daughter “fell backwards, spread out her legs, and rolled off from the cloud into the lake, where she took the form of the earth we live on.” The children of two of the women were male and female. They married “and from them all people are descended.” According to yet another account, “Old One” encountered a woman who was alone and very unhappy about her situation. To make her happy, “Old One” transformed her into “the earth, which he made expand, and shape itself into valleys, mountains, and plains.” Her blood dried up and became “gold, copper and other metals.” Then “Old One” moved on to “make the Nicola country.” He then created “four men and a woman,” (some thought “four women”) who became the first inhabitants. After teaching them how to survive, he left. But before doing so, he promised to return at which point “your mother, the Earth, from whom all things grow will again assume her original and natural form.”36

The collections were just as divided on the subject of Coyote. In fact, Teit recorded so many varied Okanagan perspectives on Coyote that he added a note to highlight this point:

Some think Coyote belonged to the earth, like other people. He was an Indian, but of greater knowledge and power than the others. Some think he was one of the semi-human ancients. Others think he did not belong to this world, but to some other sphere, such as the sky or spirit-land. Still others think he was a kind of deity or chief, or helper of the Chief, before he came to earth. In the opinion of some Indians, Coyote acted with a purpose, and knew that he had been sent to fulfill a mission. Others think he did not know, but that his actions were prompted by some other power, and that he did not transform the monsters or perform other acts for the purpose of benefiting mankind. All agree that he was selected for the mission he performed; but whether he was living in the sky when selected, or on the earth, or elsewhere, is not certain.37

Teit’s emphasis on cultural fluidity, however, was offset by others’ efforts to draw hard conclusions. Hill-Tout, for example, had claimed in 1911 that Coyote was “not a native product of the mythology of the stock” at all, but rather adopted from elsewhere.38 Heister Dean Guie, a newspaper journalist, concluded that Coyote was better understood as a children’s storybook character. With this in view, he edited and sanitized a collection of adult stories collected by Christine Quintasket. In the process, Guie turned Coyote into a generic “Imitator/Trick Person”—a fairy tale figure of sorts—who rarely acted in truly offensive ways. The book sold well. But Coyote suffered badly in the process.39

Viewed against this backdrop, Harry’s stories assumed much greater significance. His account of the twins, for example, was now one of a series of diverse creation stories maintained by his people over a long period. Similarly, his account of Coyote’s meeting with the king of England was just as distinctive a version as numerous others. Harry’s historical narratives— about unusual employees who turned up to work in local ranches—were part of an established genre of stories set in towns, farms, and ranches and featuring all sorts of people in search of jobs as blacksmiths, farmworkers, and carpenters. That Harry’s stories of white/Aboriginal conflict had few parallels in the early collections did not mean that his predecessors had not told such stories. Early collectors simply did not have any interest in them.

Comments by both Teit and Boas revealed that Aboriginal peoples were extremely eager to exchange stories about contemporary political issues. In 1916, Teit explained that his success as a salvage ethnographer depended on listening to stories about local political issues:

For many years back when engaged among the tribes in ethnological work for American and of late for the Canadian government, the Indians almost everywhere would bring up questions of their grievances concerning their title, reserves, hunting and fishing rights, policies of Agents and missionaries, dances, potlatches, education, etc. etc. and although I had nothing to do with these matters they invariably wanted to discuss them with me or get me to help them, and to please them and thus to better facilitate my research work I had to listen and given them some advice or information.”40

Although he assisted the chiefs in disseminating their contemporary histories, in political contexts, he was unable to incorporate these into his ethnographic collections.41

Boas also noted in his field diaries and letters that many of his interviewees were eager to engage him in discussions about current issues. A Squamish chief, for example, saw Boas’s interview session as an opportunity to air some of his current political concerns:

“Who sent you here?” “I have come to see the Indians and to tell the White people about them.” “Do you come from the Queen’s Country?” “No, I come from another country.” “Will you go to the Queen’s Country?” “Perhaps.” “Good, when you get there go to the Queen and tell her this. Now write down what I say: Three men came [i.e., the Indian agent and two commissioners] and made treaties with us and said this is the Queen’s land. That has made our hearts sad and we are angry at the three men. But the Queen does not know this. We are not angry at her.”42

Little of this sort of discussion made its way into his publications. Boas also noted inconsistencies among storytellers and often worried that many were telling him nothing but “nonsense.”43 Comments on this issue from his assistant, George Hunt, did not help: “You know as well as I do,” he wrote to Boas, “that you or me can’t find two Indians tell a storie alike.”44

In all of this I could see the potential for a new Harry Robinson volume highlighting the breadth of his stories. Whether they were old (i.e., “myths” about Coyote and others) or new (i.e., stories about recent murders or floods) was not of great concern to Harry. What mattered most to him was “living by stories.” He wanted to show the cultural importance of maintaining a full range of stories. If people—whites and “Indians”—knew that stumps could turn into chipmunks and that chipmunks could turn into “grandfathers,” they would cultivate a very different relationship to the land. If they knew about people like George Jim of Ashnola who had been wrongly abducted from the New Westminster prison in 1887, and Tom Shiweelkin who was wrongly killed by an early brigade of whites, they would carry a different view of their history. Knowing about large birds that could carry humans, lake creatures that could swallow horses, and grizzly bears that could shelter travellers in distress would show people that the world around them consisted of many different forms and layers of life.

Through disseminating such narratives, Harry was promoting an awareness that would generate more storytelling. That others told these stories with different twists and turns was not a concern. In fact, Harry often incorporated their twists into his own stories. And although he would never tamper with storylines or fictionalize any part of a story, he incorporated seemingly extraneous details where he felt they belonged. For example, when he learned that whites had landed on the moon, Harry immediately incorporated this detail into his story about Coyote’s son’s trip to and from an upper world.

While assembling the first two volumes, I had not appreciated the full scope of Harry’s perspective on storytelling. Along with several generations of scholars and others, I had been seduced by the Boasian paradigm which reified the mythological past and promoted the stereotype of the “mythteller”—the bearer of the single, communal accounts rooted in the deep past. Harry’s stories about Coyote’s meeting with the king and others about cats, cows, horses, and everyday animals doing supernatural things did not fit this model. But no amount of editing would make a “mythteller”45 of Harry Robinson. He would have been insulted had the label been applied to him. He was a storyteller in the broadest sense of the term.

Harry had stressed in 1984 that he was “going to disappear and there will be no more telling stories.” At the time, I assumed that he was referring to the demise of his stories. However, when I re-listened to this comment, I realized that I had missed his point. He perceived his death as a blow to the process of storytelling. He had worked hard over the years to ensure its well being. In the 1970s he had painstakingly adapted all of his stories in English to accommodate a growing number of listeners who spoke little or no Okanagan. Through the 1980s he had submitted these English versions of his stories to audio tape so that they could carry on without him. He had also spent afternoons in his local band office telling stories in his Okanagan language. His final move was to release his oral stories in book form so that they would reach a broad audience “in all Province in Canada and United States” (letter, 27 January 1986).

Living by Stories brings Harry’s objective closer to fruition. And once again, Coyote looms large. The way Harry put it, everything hinged on the book produced by Coyote and the king. Although he never read its contents, he knew the story about it and that was what mattered. He would pass the story on through his own book. And its message would be clear to all: that whites were a banished people who colonized this country through fraudulence associated with an assigned form of power and knowledge which had been literally alienated from its original inhabitants.

NOTES

1. Two members of our party, Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy, knew Harry well. They had notified him in advance of our visit. The third member was Michael M’Gonigle.

2. Paul Radin, The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology (New York: Schoeken Books, 1956); Gary Snyder, The Old Ways (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1977); and Barry Lopez, Giving Birth to Thunder, Sleeping with His Daughter, Coyote Builds North America (New York: Avon Books, 1977).

3. James A. Teit, Marian K. Gould, Livingston Farrand, and Herbert J. Spinden, in Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes, ed. Franz Boas (New York: Stechert & Co., 1917); Charles Hill-Tout, “Report on the Ethnology of the Okanaken of British Columbia, an Interior Division of the Salish Stock,” in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 41 (1911): 130–161 (reprinted in Ralph Maud, ed., The Salish People: The Local Contribution of Charles Hill-Tout, Volume 1: The Thompson and the Okanagan [Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1978], 131–159); and Leslie Spier, ed. (with Walter Cline, Rachel S. Commons, May Mandelbaum, Richard H. Post, and L. V. W. Walters), The Sinkaietk or Southern Okanagon of Washington (Menasha, Wisconsin: George Banta Publishing Co., 1938).

4. Mourning Dove, Coyote Stories (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Publishers, 1933; reprint, Jay Miller, ed., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990).

5. Franz Boas, Indianische Sagen von der Nord-Pacifischen Küste Amerikas (Berlin: A. Asher & Co., 1895); for a recent English translation of this work, see Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy, eds., Indian Myths & Legends from the North Pacific Coast of America (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2002); James A. Teit, Traditions of the Thompson River Indians of British Columbia (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1898); and id., “Mythology of the Thompson Indians,” vol. 8, part 2 (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1912), 199–416.

6. Teit, Traditions, 28. The Latin segment appears in footnote 73 on p. 105.

7. I am grateful to Lynne Jorgesen for this comment.

8. Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966).

9. Stith Thompson, The Folktale (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 9.

10. A quick survey of the historical records uncovered nothing about John P. Curr. Historian Richard Mackie concluded on the basis of the pack train, the men with uniforms, the mention of a few white men living here and there, and the execution of the chief that the setting for this story was probably circa 1858–62. He noted that it seemed typical of “the American overland militaristic migration to the Fraser or Cariboo gold rushes.” Mackie explained that the chief would not have had a letter from Ottawa before 1871; however, he could well have had such a letter from a surveyor or a government employee from Victoria or New Westminster by then. He dated it at 1858–59 (e-mail correspondence, 1 August 2005). Historian Dan Marshall offered a similar view. He suggested that Curr’s brigade may have consisted of miners. “Starting in 1858,” he explained, “large companies of miners, many of them old Indian fighters, took the Columbia-Okanagan route to the BC goldfields. These companies ranged in size, many of them amounting to hundreds. The number of deaths that occurred on either side of the border during that year suggests that 1858 may be the time period in question, references to Ottawa and Vancouver aside” (email correspondence, 5 August 2005).

11. Vancouver and Penticton: Talonbooks and Theytus Books, 1989.

12. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1992; reprint, Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2004.

13. See, for example the following: James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988); David Murray, Forked Tongues: Speech, Writing and Representation in North American Indian Texts (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991); Michael Harkin, “Past Presence: Conceptions of History in Northwest Coast Studies,” Arctic Anthropology 33, no. 2 (1996): 1–15; Judith Berman, “‘The Culture As It Appears to the Indian Himself’: Boas, George Hunt, and the Methods of Ethnography,” in George W. Stocking, Jr., ‘Volksgeist’ As Method and Ethic: Essays on Boasian Ethnography and the German Anthropological Tradition (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), 215–256; Rosalind Morris, New Worlds from Fragments: Film Ethnography, and the Representation of Northwest Coast Cultures (Boulder: Westview Press, 1994).

14. Michael Harkin, “(Dis)pleasures of the Text: Boasian Ethnology on the Central Northwest Coast,” in Gateways: Exploring the Legacy of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, 1897–1902, eds. Igor Krupnik and William W. Fitzhugh (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 93–105.

15. Jonathan D. Hill, ed., Rethinking History and Myth: Indigenous South American Perspectives on the Past (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988).

16. Terence Turner, “Ethno-Ethnohistory: Myth and History in Native South American Representations of Contact with Western Society,” in Rethinking History and Myth, ed. Jonathan D. Hill, 174.

17. Emilienne Ireland, “Cerebral Savage: The Whiteman as Symbol of Cleverness and Savagery in Waura Myth,” in Rethinking History and Myth, 172. In British Columbia, anthropologists Julie Cruikshank and Robin Ridington were drawing attention to similar issues. See Julie Cruikshank, Life Lived Like a Story: Life Stories of Three Yukon Elders (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990) and id., “Images of Society in Klondike Gold Rush Narratives: Skookum Jim and the Discovery of Gold,” Ethnohistory 39, no. 1 (1992): 20–41. See also Robin Ridington, Trail to Heaven: Knowledge and Narrative in a Northern Native Community (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1988) and id., Little Bit Know Something: Stories in a Language of Anthropology (Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1990).

18. Hill-Tout, in Maud, The Salish People, Vol. 1, 137.

19. Ibid., 149.

20. James A. Teit, New York City: Fieldnotes, Anthropology Archives, American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

21. Teit et al., Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes, 34.

22. Boas, Indianische Sagen, 52.

23. Ronald Rohner, ed., The Ethnography of Franz Boas: Letters and Diaries of Franz Boas Written on the Northwest Coast from 1886–1931 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 99–100. For a more detailed examination of this story, see Wendy Wickwire, “Prophecy at Lytton,” in Voices from Four Directions: Contemporary Translations of the Native Literatures of North America, ed. Brian Swann (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 134–170.

24. For more on this, see Judith Berman, “The Culture As It Appears to the Indian Himself.” See also Charles Briggs and Richard Bauman, “‘The Foundation of All Future Researches’: Franz Boas, George Hunt, Native American Texts, and the Construction of Modernity,” American Quarterly 51, no. 3 (1999): 479–527.

25. For more on James Teit’s political activism, see Wendy Wickwire, “‘We Shall Drink from the Stream and So Shall You’: James A.Teit and Native Resistance in British Columbia, 1908–22,” Canadian Historical Review 79, no. 2 (1998): 199–236.

26. Teit, “More Thompson Indian Tales,” Journal of American Folklore 50, no. 196 (1937): 173–190.

27. Teit, Philadelphia: Fieldnotes, American Philosophical Society (APS).

28. Teit, “More Thompson Indian Tales,” 170.

29. Ibid., 180.

30. Ibid., 184.

31. Ibid., 173. Footnote 1 explains that “the following hitherto unpublished tales have been taken from manuscripts by the late James A. Teit and edited by Lucy Kramer.”

32. Teit et al., Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes, 80–84.

33. Spier et al., The Sinkaietk, 197–198.

34. Teit, Mythology of the Thompson Indians, 320.

35. Ibid., 321.

36. Ibid., 323–324.

37. Teit et al., Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes, 82.

38. Hill-Tout, in Maud, The Salish People, Vol. 1, 134.

39. Mourning Dove, Coyote Stories. See also Alanna K. Brown, “The Evolution of Mourning Dove’s Coyote Stories,” Studies in American Indian Literatures 4, nos. 2 & 3 (1992): 161–179. A new collection of stories recorded by Darwin Hanna and Mamie Henry—Our Tellings: Interior Salish Stories of the Nlha7kapmx People (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1995)—helped to reverse this trend. Herb Manuel’s presentation of Coyote was never static or abstract. In fact, Manuel described Coyote so vividly that one would think that he had met Coyote: “He was kind of always undernourished. He was, in human flesh, a skinny, tall man with drawn-in cheeks [who] … spoke with a drawn-in voice. He spoke funny. You knew it was him when you heard his voice” (32).

40. National Archives, RG10, vol. 7781, file 27150-3-3, Teit to Duncan Campbell Scott, 2 March 1916.

41. One notable document, a “Memorial to Laurier,” presented by the Interior chiefs to Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier at Kamloops in 1910, was a history of the nineteenth century from the perspectives of the chiefs. For more on this, see Wickwire, “James A.Teit and Native Resistance,” 1998.

42. Rohner, The Ethnography of Franz Boas, 86.

43. Ibid., 38.

44. Ibid., 239.

45. British Columbia poet Robert Bringhurst has recently introduced the term “mythteller” to the British Columbia anthropological lexicon. Based on his study of the Haida oral narrative collections of Boasian ethnographer John Swanton, Bringhurst concluded that the storytellers were “mythtellers.” See A Story As Sharp As a Knife: The Classical Haida Mythtellers and Their World (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1999).