Читать книгу Ruud Gullit: Portrait of a Genius - Harry Harris - Страница 8

CHAPTER ONE âIâm not a foreigner â Iâm a world travellerâ

ОглавлениеRuud Gullit loves to talk. He is knowledgeable on a wide range of subjects, of which football is not top of the list. But he doesnât just talk for the sake of it. He sees himself as a teacher and nothing seems to give him greater pleasure than an appreciative audience. He likes nothing better than to impart his wealth of, knowledge about the game to others, whether they are team-mates or journalists. In his company I have been riveted by his wide range of subjects â including adoption, surrogate mothers, and environmental issues. Ruud would rather switch on the television to watch a fascinating documentary than bore himself with an uninteresting football match.

I followed Jurgen Klinsmannâs one and only glory season in English football and there are numerous similarities. There are also some stark contrasts. The smiling German symbolised English soccer, season 1994/95. Every magazine, newspaper, radio and television programme featured Jurgenâs endearing features. The World Cup star came to English football with a reputation of diving, but he did the right things, said the right things, smiled, and won the hearts and minds of the footballing nation. But after a while Klinsmannâs interviews seemed to merge into one. Then he âbuggered offâ, as Alan Sugar put it succinctly, after just one season, and the Spurs chairman raised suspicions about the Germanâs motives. Things came to a head during an interview for BBCâs Sportsnight programme, when Sugar threw Klinsmannâs Tottenham shirt to the floor in disgust.

Whether or not Klinsmann came for the money and to rekindle a diminishing career, the Premiership felt it would be poorer for the loss of the Football Writersâ Footballer of the Year. But the following season, Gullit and many more foreign stars arrived to play in the Premier League.

When the news of Gullitâs free transfer move from Sampdoria broke in the summer of 1995, there was the usual media speculation about the salary he would be earning in England. It was believed his original two-year deal with Chelsea amounted to around £1.6 million, a sum which would prove to be a bargain for the club, as the wages were spread over the duration of his two-year commitment without any transfer fee, at a time when prices were soaring. And now they have a successful manager as well as a player for virtually the same amount of money.

When Gullit first arrived at the Bridge, Ken Bates recalls how money was the last thing on the Dutchmanâs mind. âIâll tell you a little secret about Ruud which sums up the man perfectly. Ruud had been at the club a couple of months and he still hadnât bothered to open an English bank account. Colin Hutchinson called him over and said to him: âIâve got your wage cheques here.â Ruud told him, âDonât worry, Colin, youâre my banker. Keep the cheques in the drawer until I need them!â

âHeâs got a lovely dry sense of humour. He is also very polite and respectful. One match day he spotted me before the game at my table and came over. I looked up at his dreadlocks and got out a comb. He just burst out laughing.

âRuud is really the perfect diplomat. He never puts a foot wrong. The only trouble heâs experienced occurs when heâs been misquoted. His influence goes much deeper than the superficial. There was annoyance within the club when he first joined that Gullit was the superstar and the rest didnât matter and that they were not good enough. It was patently untrue, but it hurt. Then, when Gullit was injured, the team won as many games without him as they did when he was in the team. Thatâs not belittling his contribution in any way. In fact itâs a compliment to him because it reflects his overall influence on the team whether he is playing or not. The truth is that Gullit was largely responsible for helping Glenn to get the younger players around to the managerâs way of thinking.â

But there is not a hint of indulgence at the Bridge. Ruud works as hard as anyone in training and on the pitch. His influence has been immense, his sincerity unquestioned. A testimony to his sheer genius came from England and former Chelsea manager Glenn Hoddle. âHe is enjoying his football. In this game you learn by example. The players are becoming better because of him. When I was at Chelsea we signed Ruud as a sweeper, but later in the season we moved him into midfield and a lot of that credit has to go to David Lee. He took over as sweeper and did well. Then we started getting the ball to Ruud as quickly as possible. In some games in England, midfield can be like a tennis match. But we tried to build from the back and get it to Ruud and that allows him to go and influence the play. I knew he had another three years in him when he came to Chelsea. He is fit, got the talent and is still in love with the game. While heâs got that, he is going to be a big influence at any club.â

His influence on players like Newton, Myers, Duberry, Sinclair and Furlong grew more important as the months went by and they got to know him better. Bates pointed out: âHis total indiscrimination towards colour has made a great impression on our black players, particularly the young ones.â Ruud has always been outspoken on issues of racism in soccer, and attended the FA backed âKick Racism Out of Soccerâ campaign just a couple of months after arriving in England.

Although it is widely assumed that Ruud is more effective in midfield, his first awards came as a result of his superb displays as a sweeper. Mirror Sport readers voted him the FA Premier Leagueâs Most Valuable Player of the Month for September 1995. He was also the first McDonaldâs/Shoot Player of the Month, averaging 8.25 ratings for his performances, including five man-of-the-match nominations in his first eight games. Shoot said: âHe was awarded a mark of nine out of ten in four of those great games and was head and shoulders above the rest of the Premiership stars.â

But you will never meet a more modest chap. When he was awarded the Evening Standardâs Player of the Month award for January 1996 â as an outstanding midfield player â the newspaperâs chief football correspondent Michael Hart, hardened by years in the cynical world of this particular tainted sport, was almost shocked by Gullitâs reaction. He wrote: âYou would think that someone who has touched the heights of the world game might not rank winning the Evening Standard Footballer of the Month award too highly among the golden moments of an epic career. Yet Ruud Gullit turned out to be one of the most gracious recipients of the last quarter of a century. Not just gracious, but genuinely grateful. âI couldnât have won this without the rest of the team,â he said. âThey make a lot of jokes about me in the dressing room but Iâm very happy with the guys.â To prove the point, he insisted on including the rest of the Chelsea team in the photograph and publicly thanked his colleagues who have come to appreciate the enduring influence of one of the worldâs great players. âThe first thing you want is that the team plays well,â said Gullit. âA team is like a clock. If you take one piece out, it doesnât workâ.â

Gullit became a born-again player in his first year at Chelsea. âI seem to have gone back in time. Iâm playing like itâs the beginning of my career again and that Iâm an 18-year-old again. The child in me can play on because I am still enjoying it, and if I enjoy it I can express myself better.â He also much prefers the attacking style of play over here compared to the often negative attitude back in Italy. âIn England you donât just stay back and defend,â he says. âYou are not a slave to tactics and results.â

To watch Gullitâs long-range passing is a delight. It used to be the hallmark of Hoddle himself, but somehow Gullit has a far greater degree of consistency in his passing. That is what should be meant by the long ball, instead of the kick and rush, or kick and hope. Gullit plays the short passes with carefree simplicity and the long-range missiles with uncanny accuracy. As Michael Hart wrote: âGullitâs job, wherever he plays, is quite simple. His presence, his ability on the ball, his vast stride, his vision, his range of passing ⦠all were essential to Hoddleâs doctrine. With Gullit in the side the Chelsea players had the conviction they needed to successfully interpret Hoddleâs tactics.â

A huge debate erupted during the course of the 1994/95 season over the value of imported stars, their quality and the influx as a result of the Bosman case. Gordon Taylor, of the Professional Footballers Association, was at the sharp end of the controversy with work permit problems involving Romanian World Cup star Ilie Dumitrescu. While Taylor is a concerned Euro-sceptic, he welcomed Klinsmann and laid down the red carpet for players like Gullit, Ginola, and Bergkamp. Their arrival, he believed, far from diminishing opportunities for home players that might be the case with the also-rans that join the influx, can stimulate young playersâ development. Taylor, nevertheless, insisted that while transfer turnover had reached £130 million a year, the proportion of it going to clubs in the lower divisions was falling.

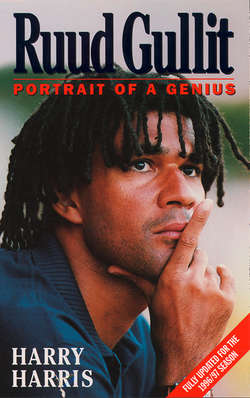

The desirability of a large number of foreign players was in question. But players of the highest quality can only enhance the English game and they donât come any higher than Ruud. As Stan Hey wrote in the Independent on Sunday: âGullit, whose magnificent physique and twirling dreadlocks are dramatic enough prologues even before he touches a ball, is probably the most prestigious import to the English game since Osvaldo Ardiles arrived at Tottenham with his World Cup winnersâ medal.â

The acquisition of Gullit was so natural for Hoddle after his decision to finally end his own illustrious playing career. Hoddle began his three-year stint as a player-manager at the Bridge in the sweeper role. He believed he had found the perfect player to fill the void. Hoddle, explaining the original concept for signing Gullit, said: âI earmarked him three months before the end of the 1994/95 season when I was looking for a sweeper. The big question was whether we could get him. I thought at first it would be a struggle to afford him. Then, when I discovered he was on a free transfer, I couldnât believe it. It proved to be a long, hard struggle to sign him, but I was convinced it was going to be a worthwhile struggle.â

Gullitâs pre-requisite for any move from Italian football was the freedom to fulfil his desire to return to playing in a sweeper system. He was determined to make it work. But he equally accepted without complaint a switch to midfield where he became the cornerstone of Chelseaâs transformation. Gullit was prepared to forsake his desire to play sweeper because of his respect and affection for Hoddle. Equally, Hoddle was ready to ditch his original conception of Gullitâs role for the overall benefit of the team, yet still retain his philosophy of playing three at the back with David Lee taking over as the sweeper.

Right from the outset Gullit had an affinity with Hoddle as he explained at the start of the 1995/96 season: âI like the way Glenn thinks about football. The reason I came to Chelsea is that it is one of the English clubs managed by an English player who has played abroad. Glenn Hoddle, like Kevin Keegan, wants more than just kick-and-rush football. Because if you keep possession of the ball, you can dictate the game, and wait for the right moment to attack. Most of the Premiership teams play more on the ball now, which is one of the reasons the rest of Europe has become so positive about the English game. If we have the ball, we can play to our own rhythm, rather than allow our opponents to play the ball at high speed. If you always have the ball, you can direct the game.â

It only took a few games for Gullit to appreciate that his sweeper role in English football would not be permanent. Gullit was never going to be dictatorial about his role as he explained from the very outset: âIn my career, coaches and managers have always tried to play me in different positions. I happen to be a player who can play in almost every position. Sometimes thatâs a bonus, sometimes it can be a disadvantage. I can say I claim the sweeper position for the entire season, but if we get problems up front I might be asked to go and play there.

âWhen I started playing as a kid it was as a libero because I was big and kicked very hard,â he said. âI played there when I turned professional, but my club always needed someone strong up front. I went up front, made a lot of goals, which was my fault,â he joked. âThen they needed someone on the right wing. I did well on the right wing, then PSV wanted me as a libero and I did well there. Then they needed someone up front, so I played up front and made goals â and so it has carried on.â

Ruud absorbs a great deal of information and has a wide range of interests. Unlike the archetypal footballer whiling away those hours of free time watching football videos, drinking, betting or going to the dogs, Gullit has been hooked by the wide range of documentary programmes on television. After the second home match of the season, a thrilling, if disappointing 2â2 draw with Coventry, Gullit sat in the near deserted Bridge press room close to the dressing rooms discussing philosophy with a handful of journalists who could be bothered to wait until he had conducted an assortment of television and radio interviews. With a twelve-day break before the next match because of international games, Gullit was asked if he would indulge in catching up with English football by watching videos of matches. Not at all. Instead, he would continue his television diet of serious programmes. He said: âI watch football on TV but not all the time. There are a lot more important things to see. Certain things are fascinating. One was about Siamese twins, and how the surgeons decided to separate them. One of the girls survives but misses her sister and even names her false leg after her twin. That touches you. You see what the children have to endure. You see the problems of autistic children and imagine how the parents have to live with it. Your whole life can be occupied by the plight of children. You see how lucky you are.

âAnother was about a new cure for Parkinsonâs disease. I was watching this guy with his flailing arms and the surgeon drilling into his brain. You see the result, he is able to control himself and walk, and that is really something special. Things like this are the real world. You compare all this with what is happening to you. You can learn a lot about it. Football is part of life, but it is entertainment. There are other, more important things. These documentaries give you other aspects of life, something special, something emotional. Football doesnât rule my life.â

It was a remarkable insight into Ruudâs perspective of life, as he was willing to talk endlessly about his innermost feelings when he watched those documentaries. He seemed less inclined to open up about his football!

The 1995/96 Premiership season kicked off with a fascinating portrait of Gullit in The Times by their chief soccer writer Rob Hughes. He wrote: âIn many ways, Gullit is the symbol of what is happening to the English game in this hot, lazy, crazy summer. We are no longer buying cheap imports from eastern Europe, but men of character, status, achievement.â

However, The Times article posed pointed questions about Gullitâs fitness, and desire. âDoes he arrive here too late, and diminished after the fearful injuries to his knees, the two failed marriages so ruthlessly exposed by the paparazzi?â

Gullit answered this straight away with an impeccable debut in the Premiership and with it the promise of real success for Chelsea after such a long wait. Goals were hard to come by at the start of the season for the Blues, but Gullit was their most effective player â in defence, midfield and attack!

Hoddle is convinced that Ruud can continue to play in the top flight. He has already seen enough to suggest that Gullit is as fit as ever. He says: âThere is no reason why he cannot go on until he is 37 or 38. Some people have been surprised by how fit he is, but I am not. I wouldnât have bought him if I hadnât done my homework. He is a real professional and looks after his body. Only people who love the game can play until that age. He knows that when he hangs up his boots he can abuse his body all he wants then. But while he loves the game and looks after himself, he has the vision to play on for years to come.â

Gullit adapted quickly to the contrast in philosophies from Italian football. So quickly that any thought of a culture shock was instantly dismissed. While he praises the game over here for a variety of reasons, he is critical of standards of the English game in Europe and world football. âThe Italian game is based on winning. How you win is unimportant. Here, the game is far more open and exciting and people all over the world love to watch it. But you donât win anything. The records show that and it was proved again last season. I love the game in England, but its future depends on the coaches. They have to make a choice.â

In his first season in English football, the prominent club sides failed miserably in Europe. Yet again the English League champions had failed to get past the first stage of the Champions League. Gullit observed: âSince Iâve been here Iâve seen some good teams, but Iâm surprised they still struggle in Europe. Sometimes they forget that teams are like cars, they have five gears, but some teams play in fourth and fifth gear all the time. You need to start off in first gear to get things moving. Liverpool can play in different gears. In Europe you have to learn patience. The English game is fast, the idea is to play the ball as quickly as possible into the box. In Europe, they play another game and English clubs may need to adapt themselves. And that will require more training and thinking about tactics.â

After a virtuoso performance at Loftus Road, as Chelsea beat QPR in the fourth round of the FA Cup, Gullit wandered into the Press Room where he gave another insight into his footballing philosophy. He revealed that he could see the transformation at the Bridge taking shape. âAll credit to Glenn for this, he wants to try and play football the way it should be played. The crowd are beginning to appreciate this keep-ball. At first, they would boo if you sent the ball backwards, but sometimes it had to go backwards to find areas to go forwards. We have to depend on our skills, but we can improve still further. We have to be more clinical and weâve not got that yet. To reach the top of our capabilities we have to be more clinical in front of goal, but it is good that we are learning what we have been doing wrong.â

In the vital Cup tie at QPR, Hoddle turned to Gullit as his captain for the first time in the absence of the suspended Dennis Wise. Gullit said: âThat was an honour on for me. The gaffer came to me and said, âI want to make you captain.â I said OK.â The soccer cliché âgafferâ seemed to come naturally to Gullit, who was totally integrated with his team-mates. He said: âI was never made captain in all my time in Milan. Never.â

Ruud is also active in pro-environmental campaigns. He has been involved with plenty of environmental issues during his years but dismisses the idea that he may one day go into politics. âYou have people without scruples in politics,â he said. âThey go with the wind. But itâs not just politicians who are responsible for the world. It is all of us. You know, football is a game of 90 minutes. When it is over you return to the real life. There are many things in life other than football.â

Whatever the future holds, for the present Ruud Gullit is captivating fans and pundits alike. Anyone privileged to be in his company for an interview cannot help but come away with a warm inner glow. At last, we have a player without a chip on his shoulder, a diabolical disciplinary record, or the inability to express himself.

Clive White, in an article for the Sunday Telegraph, observed: âA few minutes spent in Gullitâs company is enough to make one realise that here is a man in pursuit of excellence, whether it be for the betterment of himself or his team, rather than some monetary goal.â

Gullitâs stature and class have never been questioned. And, once he established his commitment to English football, and produced near perfect performances in virtually every game in which he played for Chelsea, some of the more respected pundits began to warm to him even more.

Brian Glanville, in his analysis of the glut of foreign players, wrote in the Sunday People: âSupreme among them all of course is Ruud Gullit, even if his age and those knee operations mean you canât expect him to run around for 90 minutes. But Gullit is so much more than a schemer â heâs âtotal footballâ personified. Sweeper, striker, midfielder: call him what you will. What he proves, game by game, is that a player with high technique and real imagination is worth his weight in gold.â

However, Gullit doesnât consider himself to be a foreigner. âIâm not a foreigner,â he says. âIâm a world traveller.â