Читать книгу Undoing Border Imperialism - Harsha Walia - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

Оглавлениеthis is the year that those

who swim the border’s undertow

and shiver in boxcars

are greeted with trumpets and drums

at the first railroad crossing

on the other side;

this is the year that the hands

pulling tomatoes from the vine

uproot the deed to the earth that sprouts the vine,

the hands canning tomatoes

are named in the will

that owns the bedlam of the cannery;

this is the year that the eyes

stinging from the poison that purifies toilets

awaken at last to the sight

of a rooster-loud hillside,

pilgrimage of immigrant birth;

this is the year that cockroaches

become extinct, that no doctor

finds a roach embedded

in the ear of an infant;

this is the year that the food stamps

of adolescent mothers

are auctioned like gold doubloons,

and no coin is given to buy machetes

for the next bouquet of severed heads

in coffee plantation country.

—Martin Espada, “Imagine the Angel of Breads”

This book is about undoing borders—undoing the physical borders that enforce a global system of apartheid, and undoing the conceptual borders that keep us separated from one another. Such visions are in the service of stubborn survival, and hold the vehement faith that there are millions subverting the system and liberating themselves from its chains. Just over the year that this book was written, hundreds of thousands have defiantly taken to the streets and won victories as part of the Idle No More movement, Quebec student strike, Tar Sands blockade, Arab Spring uprising, European-wide antiausterity strike, Undocumented and Unafraid campaign, and Boycott Divest Sanctions movement.

This work is a humble project; a modest effort born out of a decade of social movement organizing, for which no single individual can take credit or attempt to objectively describe. Writing this book has been a journey of overcoming my trepidation in documenting and sharing experiences related to a movement in which I have been deeply involved, yet in which I am not alone. I have had countless mentors and comrades who have challenged and influenced my thinking. I want to be explicit about these relationships given the individualistic nature of writing and the tendency toward celebrity culture in activism. There is no liberation in isolation; indeed, there is no liberation possible in isolation. This book reflects the collective and collaborative nature of social movements, and is the achievement of all those who informed its content, those who helped to edit and mold it, those whose voices and artwork are contained within these pages, and most important, those who daily self-determine and inspire rebellions and resurrections that are worth writing about.

Undoing Border Imperialism is also the piecing together of my own exiled living. My commitment to fighting state-imposed borders, which divide the rich from the poor, white bodies from brown/black bodies, the West from the Orient, is etched in blood. My mother’s family is a product of the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan—a colonially created border that displaced twelve to fifteen million people within four years. My father spent most of his adult life as a migrant worker subsisting on a daily diet of sweat, prayers, once-a-week long-distance phone calls, and the indignity of always being a “foreigner.” I have lived with precarious legal status for years and have seen the insides of an inhumane detention center. Though this book is not an autobiography, these personal experiences, memories, and stories are inseparable from the movements I am a part of and shape much of the analysis that I present in this book.

Undoing Border Imperialism

Borderlands, the ultimate Achilles’ heel of colonialism and imperialism.

—Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, “Invasion of the Americas and the Making of the Mestizocoyote Nation”

The experiences of my family and other displaced migrants—what to Chicana feminist Cherríe Moraga is actually indescribable: “to gain the word, to describe the loss, I risk losing everything”—take place in the context of broader systemic forces.(1) Mainstream discourses, and even some segments of the immigrant rights movement, extol Western generosity toward displaced migrants and remain silent about the root causes of migration. But as Nobel laureate Amartya Sen explains, “Increased migratory pressure over the decades owes more to the dynamism of international capitalism than just the growing size of the population of third world countries.”(2) Capitalism and imperialism have undermined the stability of communities, and compelled people to move in search of work and survival.

Capital, and the transnationalization of its production and consumption, is freely mobile across borders, while the people displaced as a consequence of the ravages of neoliberalism and imperialism are constructed as demographic threats and experience limited mobility. Less than 5 percent of the world’s migrants and refugees come to North America.(3) When they do, they face armed border guards, indefinite detention in prisons, dangerous and low-wage working conditions, minimal access to social services, discrimination and dehumanization, and the constant threat of deportation. Western states therefore are undoubtedly implicated in displacement and migration: their policies dispossess people and force them to move, and subsequently deny any semblance of livelihood and dignity to those who can get through their borders.

Border imperialism, which I propose as an alternative analytic framework, disrupts the myth of Western benevolence toward migrants. In fact, it wholly flips the script on borders; as journalist Dawn Paley aptly expresses it, “Far from preventing violence, the border is in fact the reason it occurs.”(4) Border imperialism depicts the processes by which the violences and precarities of displacement and migration are structurally created as well as maintained.

Border imperialism encapsulates four overlapping and concurrent structurings: first, the mass displacement of impoverished and colonized communities resulting from asymmetrical relations of global power, and the simultaneous securitization of the border against those migrants whom capitalism and empire have displaced; second, the criminalization of migration with severe punishment and discipline of those deemed “alien” or “illegal”; third, the entrenchment of a racialized hierarchy of citizenship by arbitrating who legitimately constitutes the nation-state; and fourth, the state-mediated exploitation of migrant labor, akin to conditions of slavery and servitude, by capitalist interests. While borders are understood as lines demarcating territory, an analysis of border imperialism interrogates the modes and networks of governance that determine how bodies will be included within the nation-state, and how territory will be controlled within and in conjunction with the dictates of global empire and transnational capitalism.

Borders are, to extrapolate from philosophers Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, concurrently transgressed (when extending the reach of empire) and fortified (when policing the territorial center).(5) Border controls are most severely deployed by those Western regimes that create mass displacement, and are most severely deployed against those whose very recourse to migration results from the ravages of capital and military occupations. Practices of arrest without charge, expulsion, indefinite detention, torture, and killings have become the unexceptional norm in militarized border zones. The racist, classist, heteropatriarchal, and ableist construction of the legal/desirable migrant justifies the criminalization of the illegal/undesirable migrant, which then emboldens the conditions for capital to further exploit the labor of migrants. Migrants’ precarious legal status and precarious stratification in the labor force are further inscribed by racializing discourses that cast migrants of color as eternal outsiders: in the nation-state but not of the nation-state. Coming full circle, border imperialism illuminates how colonial anxieties about identity and inclusion within Western borders are linked to the racist justifications for imperialist missions beyond Western borders that generate cycles of mass displacement. We are all, therefore, simultaneously separated by and bound together by the violences of border imperialism.

Discussing border imperialism also foregrounds an analysis of colonialism. Colonially drawn borders divide Indigenous families from each other. Just as the British Raj partitioned my parent’s homeland, Indigenous communities across Turtle Island have been separated as a result of the colonially imposed Canadian and US borders. Indigenous lands are increasingly becoming the battleground for settler states’ escalating policies of border militarization. In southern Arizona, for example, the O’odham have been organizing against the construction of the US-Mexico border wall, part of which would run through the Tohono O’odham reservation and make travel to ceremonial sites across the border more difficult. Alex Soto, a Tohono O’odham arrested for occupying US Border Patrol offices in 2010, states that the

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Border Patrol, Immigration Custom Enforcement, and their corporate backers such as Wackenhut, are the true criminals. . . . Indigenous Peoples have existed here long before these imposed borders, and Elders inform us that we always honored freedom of movement. . . . The impacts of border militarization are constantly being made invisible in and by the media, and the popular culture of this country. . . . Border militarization destroys Indigenous communities.(6)

Borders also factionalize heterogeneous communities and rigidify allegiances to artificially homogenized statist nationalisms. Multiracial Indigenous feminist Jessica Danforth writes, “What the border has done to far too many of our First Nations communities is horrific and atrocious on so many levels—and it has poisoned our minds to think in singular factions, instead of a full circle. . . . We belong to Mother Earth in whom no one has claim over—and where there aren’t any borders.”(7)

Rather than conceiving of immigration as a domestic policy issue to be managed by the state, the lens of border imperialism focuses the conversation on the systemic structuring of global displacement and migration through and in collusion with capitalism, colonial empire, state building, and hierarchies of oppression. These interrelated and overlapping forces of political, economic, and social organization shape the nature of migration, and hence inform the experiences of migrants and displaced peoples. Australian author McKenzie Wark reminds us, “Those who seek refuge, who are rarely accorded a voice, are nevertheless the bodies that confront the injustice of the world. They give up their particular claim to sovereignty and cast themselves on the waters. Only when the world is its own refuge will their limitless demand be met.”(8) From May Day marches of millions of undocumented migrants in the United States and riots of immigrant youths in France to weekly detention center protests in Australia and daily mobilizations against the Israeli apartheid wall, localized resistances are manifestations of a global phenomenon affirming the freedom to stay, move, and return in the face of border imperialism. Indigenous Secwepemc artist Tania Willard observes, “Fences and borders can’t stop the flow of rivers, migration of butterflies, or the movement of people, and won’t stop the spirit of freedom.”(9)

Undoing border imperialism would mean a freer society for everyone since borders are the nexus of most systems of oppression. While this book focuses on mobilizing against state borders, borders and the violences they enforce surround us. Much like immigration laws criminalizing migrants for transgressing state borders, trespass and private property laws outlaw squatting and the common use of space, while legalizing the colonial occupation and division of Indigenous lands. Interrogating such discursive and embodied borders—their social construction and structures of affect—reveals how we are not just spatially segregated but also hierarchically stratified. Whether through military checkpoints, gated communities in gentrified neighborhoods, secured corporate boardrooms, or gendered bathrooms, bordering practices delineate zones of access, inclusion, and privilege from zones of invisibility, exclusion, and death. Everywhere that bordering and ordering practices proliferate, they reinforce the enclosure of the commons, thus reifying apartheid relations at the political, economic, social, and psychological levels. Palestinian scholar Edward Said writes, “Just as none of us is outside or beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imagining.”(10)

Decolonizing Movement Borders

Maybe home is somewhere I’m going and never have been before.

—Warsan Shire, “To Be Vulnerable and Fearless: An Interview with Writer Warsan Shire”

Beyond conceptualizing border imperialism, this book is about migrant justice movements undoing border imperialism. As queer black educator Darnell Moore remarks, “To live, we must put an end to those things that would, otherwise, be cause for our own funerals.”(11) The process of grassroots community organizing—resisting together and building solidarities against the various modes of governance constituted through borders—leads to the generation of transnational relations, which novelist Kiran Desai calls “a bridge over the split.”(12) It is through this kind of active engagement against imperialism, capitalism, state building, and oppression—along with the nurturing of emancipatory and expansive social relations and identities, forged in and through the course of struggle—that visionary alternatives to border imperialism can be actualized.

All movements need an anchor in a shared positive vision, not a homogeneous or exact or perfect condition, but one that will nonetheless dismantle hierarchies, disarm concentrations of power, guide just relations, and nurture individual autonomy alongside collective responsibility. In the prophetic words of black historian Robin Kelley, “Without new visions we don’t know what to build, only what to knock down. We not only end up confused, rudderless, and cynical, but we forget that making a revolution is not a series of clever maneuvers and tactics but a process that can and must transform us.”(13) This necessitates creating concrete alternatives and strengthening relations outside the purview of the state’s institutions and its matrices of power and control. Such alternatives unsettle the state and capitalism by functioning outside their reach.

Decolonization is a framework that offers a positive and concrete prefigurative vision. Prefiguration is the notion that our organizing reflects the society we wish to live in—that the methods we practice, institutions we create, and relationships we facilitate within our movements and communities align with our ideals. Many activists argue that prefiguration involves envisioning a completely “new” society. But as a prefiguring framework, decolonization grounds us in an understanding that we have already inherited generations of evolving wisdom about living freely and communally while stewarding the Earth from anticolonial commoning practices, anticapitalist workers’ cooperatives, antioppressive communities of care, and in particular matriarchal Indigenous traditions. As theorists Aman Sium, Chandni Desai, and Eric Ritskes forcefully assert, “Decolonization demands the valuing of Indigenous sovereignty in its material, psychological, epistemological, and spiritual forms.”(14)

Enacting a politics of decolonization also necessitates an undoing of the borders between one another. Queer feminist philosopher Judith Butler unmasks and celebrates human vulnerability and interdependency: “Let’s face it. We’re undone by each other. And if we’re not, we’re missing something. If this seems so clearly the case with grief, it is only because it was already the case with desire. One does not always stay intact. It may be that one wants to, or does, but it may also be that despite one’s best efforts, one is undone, in the face of the other.”(15)

In the face of omnipresent physical and psychological colonialism, decolonization traverses the political and personal realms of our lives, and honors diverse articulations of nonhierarchical and nonoppressive association. Decolonization movements create an alternative to power through committed struggle against settler colonialism, border imperialism, capitalism, and oppression, as well as through concrete practices that center other ways of laboring, thinking, loving, stewarding, and living. Ultimately, decolonization grounds us in gratitude and humility through the realization that we are but one part of the land and its creation, and encourages us to constitute our kinship and movement networks based on shared affinities as well as responsible solidarities.

Why No One Is Illegal?

What would be the implications of acting out of love rather than the dictates of the nationalistic mind?

—Shivam Vij, “Of Nationalism and Love in Southasia”

I have been active in the migrant justice movement, specif-

ically through No One Is Illegal (NOII) groups in Canada, for over a decade. NOII is a migrant justice movement that mobilizes tangible support for refugees, undocumented migrants, and (im)migrant workers, and prioritizes solidarity with Indigenous communities. Grounded in anticolonial, anticapitalist, ecological justice, Indigenous self-determination, anti-imperialist, and antioppression politics, NOII groups organize and fight back against systems of injustice through popular education and direct action.(16) NOII groups exist across Canada, but are organized autonomously as a loose network with shared values and some ad hoc coordination. It was only in 2012 that the existing NOII groups drafted a joint statement of unity, in which we describe ourselves as “part of a worldwide movement of resistance that strives and struggles for the right to remain, the freedom to move, and the right to return.”(17)

Mapping the currents of NOII’s mobilizing and movement-based practices is critical for five reasons. First, NOII offers a systemic critique of border imperialism. This stands in contrast to more mainstream immigrant rights movements that ignore the centrality of empire and capitalism to the violence of displacement, migration, and border controls. Second, NOII’s systemic critique, as an organizing framework, facilitates a convergence of a range of social movements. Links are forged between antidetention and antiprison activists, between antipoverty movements and nonstatus communities to ensure public access to basic services, between local anticolonial organizing and anti-imperialist international solidarity organizing, and between gender justice movements’ defense of our bodies and environmental justice movements’ defense of the land.

Third, the work of NOII is multilayered. While organizing from an antistate framework, NOII also strategically navigates the state apparatus in order to win tangible victories for those facing detention and deportation. This kind of mobilizing cannot easily be dismissed as simply being reformist since it ensures that we are engaging with people who are directly impacted by the injustices of border imperialism. Being rooted and relevant in such a way amplifies the struggle for structural change and collective freedom. The careful and thoughtful balance of strategies is explored throughout this book as it is foundational to earning trust and respect for NOII’s organizing among affected community members and radicals alike.

Fourth, the mobilizing of NOII provides lessons on maintaining principled political positions while expanding communities of resistance through effective broad-based alliances. A major corporate newspaper begrudgingly acknowledges the force of NOII: “The once fringe community group . . . has grown in popularity. . . . Its crusade for undocumented migrants have made headlines and earned it recognition in the mainstream.”(18) In a time of the expansion of the nonprofit-industrial complex, NOII is an example of all-volunteer, radical, and grassroots community organizing that is sustainable, with a growing ability to capture people’s imaginations and a capacity to win victories. After nine years of grassroots organizing, for example, NOII-Toronto has not only popularized migrant justice issues but also mobilized to make Toronto the country’s first Sanctuary City, where city services are guaranteed to all regardless of their citizenship status. In an effort to discredit the cross-country popularity and effectiveness of NOII, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Jason Kenney recently denounced NOII in Parliament as “not simply another noisy activist group but hard-line anti-Canadian extremists.”(19)

Finally, returning to the words of Kelley, NOII offers a prefigurative vision for a different kind of society. The very name and its various invocations, such as “No Human is Illegal,” “Personne n’est illegal,” and “Nadie es illegal,” emphasize that all humans are inherently worthy and valuable, and that policies that illegalize human beings are legal and moral fictions. Undoing border imperialism requires that we undo power structures, while prefiguring the social relations we wish to have and the forms of leadership we wish to support. Within NOII, we take leadership from marginalized communities, particularly communities of color and Indigenous nations impacted by state controls and systemic oppression. Such methods of organizing within NOII aim to reflect our vision of antioppressive, egalitarian, and noncoercive societies.

For these reasons, an analysis of NOII’s decade-long history offers relevant insights for all organizers on effective strategies to overcome state-imposed borders as well as the barriers within movements in order to cultivate fierce, loving, and sustainable communities.

About This Book

I came to theory desperate, wanting to comprehend—to grasp what was happening around and within me. Most importantly, I wanted to make the hurt go away. I saw in theory then a location for healing.

—bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress

Undoing Border Imperialism merges different forms of theory that tend to be relegated to separate spheres: academic, movement, and experiential theories. While societal structures legitimize academic discourse as the most rigorous and objective type of theory, all three kinds of theory are invaluable. Together these forms help us to understand systemic injustice from different angles, and empower us to take action against authoritarian and oppressive systems. This book is primarily embedded in movement theory, which stems from the praxis of organizing, and experiential theory, which is based in lived realities and resistances.

The first chapter, “What Is Border Imperialism?” relies on academic theory. Drawing on critical race theory, feminist studies, Marxist analysis, and poststructuralism, this chapter theorizes and evaluates border imperialism from within intersectional pedagogy. I argue that the violence of border imperialism is a direct result of the violence of colonial displacements, capital circulations, labor stratifications in the global economy, and structural hierarchies of race, class, gender, ability, and citizenship status. Rather than victim blaming and racist stereotyping that punish migrants for irregular forms of migration and render them “illegal,” this chapter rigorously challenges the inhumane ideology of border controls that denies migrants their freedom and self-determination.

The second chapter, “Cartography of NOII,” maps out NOII’s response—as an anticapitalist, anticolonial, and antiracist migrant justice movement—to border imperialism. This is not a comprehensive history or even a summary of all NOII campaigns; rather, the chapter offers my perspective on some of the strongest formulations of NOII’s movement-based analysis and practice over the past decade. I outline the analyses and practices of direct support work, regularization of legal status for all migrants, abolition of security certificates, Indigenous solidarity organizing, and collaboration within anticapitalist movements. The strategies described in this chapter are relevant to other social movements grappling with how to be accountable to communities that are impacted by the systems we are confronting, how to strengthen alliances, and how to expand movements to effect tangible as well as transformative change.

The third and fourth chapters rely on social movement theory. Describing social movement theorizing, radical queer activist Gary Kinsman notes, “Activists are thinking, talking about, researching and theorizing about what is going on, what they are going to do next and how to analyze the situations they face, whether in relation to attending a demonstration, a meeting, a confrontation with institutional forces or planning the next action or campaign.”(20) In these chapters, I share the knowledge generated from these kinds of engagements within NOII. Rather than abstracting principles onto social movements, which can feel artificial and top down, these chapters generate principles from social movements, for a more grounded and pertinent discussion.

In the third chapter, “Overgrowing Hegemony: Grassroots Theory,” I address social movement strategies and tactics, antioppression practice, and group structure and leadership. Within these three areas, I explore current social movement debates, including building broad-based alliances while maintaining radical political principles, fostering antioppressive leadership while opposing hierarchies, and affecting tangible change while prefiguring transformation.

The fourth chapter, “Waves of Resistance Roundtable,” brings together fifteen grassroots NOII organizers to provide their own insights on some of these long-standing contentions. Their astute responses raise the level of consciousness on the nature of campaigning, organizational structure, alliances, and decolonization. Reflecting a diversity of (although not all) opinions within NOII groups, this roundtable disrupts conventional forms of writing that by privileging a single author, skew the collective and heterogeneous nature of movements. The roundtable holds the heart of this book.

The fifth and final chapter, “Journeys toward Decolonization,” discusses decolonization as a liberatory and prefigurative framework on which to base not only struggles against border imperialism but all social movements. Decolonization is rooted in dismantling the structures of border imperialism, settler colonialism, empire, capitalism, and oppression, while also being a generative praxis that creates the condition to grow and recenter alternatives to our current socioeconomic system. Decolonization necessitates a reconceptualization of the discursive and embodied borders within and between us by grounding us in the fundamental principles of mutual aid, collective liberation, and humility—not in isolation, but instead within our real and informed and sustained relationships with, and commitments to, each other and the Earth.

This book also weaves together short narratives from thirteen powerful voices of color. For many racialized people, sharing our narratives means much more than having a personal outlet. Narratives and stories are foundational to keeping our cultural practices alive and to rekindling our imaginations. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, an Indigenous Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, describes storytelling as “a lens through which we can envision our way out of cognitive imperialism, where we can create models and mirrors where none existed, and where we can experience the spaces of freedom and justice. Storytelling becomes a space where we can escape the gaze around the cage of the Empire, even if it is just for a few minutes.”(21) The stories throughout this book are not only challenges to the norms of border imperialism and settler colonialism; they are also glimpses into envisioning and actualizing egalitarian social relations.

The inclusion of these thirteen narratives, all authored by racialized and predominantly women activists and writers, is a political act. In one of the most poignant affirmations of women of color solidarities ever depicted, poet Aurora Levins Morales writes, “This tribe called ‘Women of Color’ is not an ethnicity. It is one of the inventions of solidarity, an alliance, a political necessity that is not the given name of every female with dark skin and a colonized tongue, but rather a choice about how to resist and with whom.”(22) This describes more than a solidarity based on shared identity. Women of color solidarities are based on the recognition that since the subjectivities of women of color are the most impacted by systems of oppression and exploitation, we embody the pathways necessary to concurrently disrupt multiple layers of injustice.

The thirteen voices in this book refuse to be disappeared and defy surrender. These are the tongues that were never meant to survive, the stories that were meant to be stolen and silenced through centuries of annihilation and assimilation. The centrality of these voices to this book is an enactment of antioppressive leadership—a principle that this book calls on us to heed. Given that capitalist, white supremacist, and heteropatriarchal society has taught us to fear, judge, and compete with one another, facilitating space for other women of color warriors is an intentional political practice, an offering in the spirit of decolonization.

Acknowledgments

This book was written on Indigenous Coast Salish territories. The Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil Waututh peoples, who endure acts of genocide in order for us to live with amnesia about the histories of Turtle Island, have never surrendered these lands. This book also would not be possible without the toil of those, mostly immigrant workers locally and impoverished laborers across the globe, who daily work the fields and factories that produce my basic necessities, including my food and clothing. These are the founding conditions and violences of my intellectual labor.

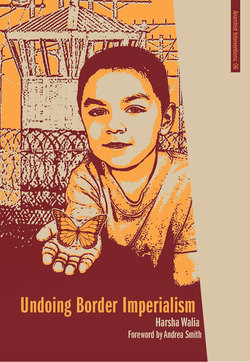

I am indebted to Hari Alluri, Lisa Bhungalia, Fariah Chowdhury, Stefan Christoff, Nassim Elbardouh, Mary Foster, Harjap Grewal, Stefanie Gude, Alex Hundert, Andrew Loewen, Cecily Nicholson, Dana Olwan, Dawn Paley, Sozan Savehilaghi, Andréa Schmidt, Parul Sehgal, Naava Smolash, and Shayna Stock for their diligent comments and edits. Any errors within this book, however, are my own. Thank you to all the brilliant contributors for their wisdom, Andrea Smith for honoring the book with a foreword, Ashanti Alston, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Naomi Klein, and Vijay Prashad for humbling blurbs, Melanie Cervantes and Josh MacPhee of Justseeds for stunning design work, Zach Blue, Christa Daring, and Charles Weigl of AK Press for publishing this manuscript, and Chris Dixon and Cindy Milstein of the IAS for soliciting, encouraging, supporting, and editing this manuscript, and essentially being the backbone of this entire process. Gratitude to ancestors, family, comrades, elders, friends, and allies who light this journey. And to my brother, who always knew that living simply and loving deeply were interconnected.

“Pick One”: Self-determination and the Politics of Identity(ies)

“Pick one,” they said

North American. Indian?

But wait, I’m from Toronto.

Although that’s not where my family is from

And I don’t live there anymore

“Pick one,” they said

Young. Woman?

But I’m not a woman like you might think I am

I’m Two Spirit beyond the acronym of LGBT

And it’s more than a sexuality

“Pick one,” they said

I work in sexual and reproductive health?

But it’s about rights and justice over body and space

Even if we didn’t want to include environmental violence

We have to since that’s what’s happening to us.

Don’t worry—I’m not interested in winning the Oppression Olympics

I know I’m complicit too

But this isn’t a two-sided story

Since there aren’t always two sides

There could just be the truth, the reality

The fact that there’s a history to this continuing

The boxes, the borders, the lines being drawn

The refusal to accept that it’s on purpose

The disguise that it’s “so much better than it used to be”

While the roots remain too close for comfort

Now they say, “We’re inclusive!”

Even though I’m not actually interested in being included

After I had to be included because I wasn’t there to begin with

They’re not looking at the center where I was erased

To uphold what makes it easier to not deal with

Now they say, “I’m your ally!”

Even though I ain’t neva seen them where I live

I don’t remember being asked if that’s what I want

There’s this thing called free, prior, and informed consent

Which doesn’t seem to apply when it’s about titles

Now they say, “We’ll get there someday!”

Even though the same patterns of oppression keep repeating themselves

I don’t want to keep swallowing the pill of having to understand

It’s not only about a better policy, law, or elected official

In the same system, it still hurts.

Unless things are dismantled and deconstructed where there’s pain

Regrounded and rebuilt where there’s hope

It will still be messed up for some

Always that same sum

Who never fit nicely into an equal opportunity

I’ve failed applications, funding proposals, membership, and residency tests

The same organizations and groups won’t call me

“You’re just too mixed!” I’m told

But I don’t feel mixed, I feel whole

And I’m not the only one.

Every explanation I have to give because my story isn’t shown in the mainstream

Every but I have to put in front of what I call myself in the English language

Every discussion I have to get into because I will not allow my ancestors’ struggles for me to be here to be silenced

Takes away my self-determination of identity

If you want to stop the us vs. them

I just can’t pick one.

—Jessica Danforth

Chile Con Carne

Manuelita walks slowly toward her desk. Music resembling the sound of a heartbeat plays.(1) MANUELITA: At school nobody knows I dance cueca. Nobody knows I work at the bakery and at the hair salon. Nobody knows my house is full of my parents’ friends having meetings till really late. Nobody knows we have protests and rallies, nobody knows we have penas and cumbia dances, nobody knows my parents are going on a hunger strike. Nobody knows my dad was in jail. Nobody knows we’re on the blacklist. Nobody from school, not even Lassie, comes over to my house. Nobody knows we have posters of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara on the walls. Nobody knows about the Chilean me at school.

Manuelita arrives at her desk. The man from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police is here to talk about safety. So stupid! MANUELITA: He’s a huge gringo policeman, with a gun at his side. I bet he knows that me and Joselito broke the windows on the tractors that want to chop down Cedar, my favorite tree, and now he’s come to get me. Then I’ll be in jail. Just like my dad was. He’s standing at the front of the class with a nice warm smile on his face. “Hi, kids,” he says. I remember those nice grins, those are the same grins they wore when they raided our house and they tore my favorite doll’s head off. I sit in the first row of desks so I can see the gun real clearly. It’s real all right, but it’s smaller than the ones in Chile. The man starts talking about dangerous men in the woods and never get in cars and never take money from strangers, but I’m thinking, I know. I know what you’re really about. My mom explained to me once that the gringos helped to do the coup in Chile, that’s why we always have protests outside the US consulate, so I know what you’re up to, mister. You’re trying to get us to trust you, but “No, sir.” He takes his gun out slowly and holds it like this, flat in his hands; he’s talking about how he never uses it, when all of a sudden I hear a kid screaming real loud. A few moments go by before I realize it’s me that’s screaming.

Manuelita stands on the desk and does a silent scream, turning in a circle. Then she sits back down. MANUELITA: There’s a puddle of pee on my seat. Miss Mitten comes up to me with a frozen smile and eyes that are about to pop out. She hits me on the head with her flash cards.

Manuelita runs to Cedar. MANUELITA: I can hear the kids laughing ’cause I peed, but I run all the way home and here, to Cedar.

—Carmen Aguirre

The Bracelet

This is a dialogue between a father and his four-year-old son.(1)

“Dad, dad . . .”

“Yes, little one.”

“What are you wearing around your neck?”

“Around my neck! Nothing.”

“No, there.”

“Oh, you mean around my ankle?”

“That’s the neck of your foot, the annk . . . what?”

“Ankle, little one.”

“But you didn’t tell me what it is.”

“Ah. That, that’s a bracelet.”

“How long have you been wearing it?”

“Three years.”

“Why do you always wear it?”

“Because I’m attached to it; it was a present.”

“Who gave it to you?”

“It was tonton.”

“Who is tonton?”

“Er . . . it’s Uncle Sam.”

“Who is Uncle Sam?”

“Little one, you ask too many questions. It’s just somebody who gave it to me . . . Uncle Sam, Uncle Stephen, Uncle Security. It doesn’t matter; you don’t know him.”

“OK, but why is it black, your bracelet?”

“Because those who gave it to me have white faces but black hearts.”

“Why isn’t it gold, like mama’s necklace?”

“Because those who gave it to me don’t have a heart of gold, little one.”

“But Dad, why are you the only person who wears it in Quebec?”

“Not for long, little one, don’t worry. In not too long it’ll be a style, like tattoos; everyone will have theirs. There are already ones in cell phones, in cars, for blue-collar workers, for grandfathers, for babies, for dogs. . . . Uncle Sam doesn’t have a heart of gold but he doesn’t miss anyone.”

—Adil Charkaoui

Imposters

The world is made up of imposters. There is often a will towards authenticity, some semblance of the genuine. And yet, what might it mean to consider the figure of the imposter, not as an aberration or crime but as a standard. To play a part is to perhaps hold a role in the increasingly neoliberal global economy.

In Delhi, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Lahore, she will smile into a headset. Her voice will chirp with the intonations of Friends actresses whom she has learned to mimic. Her English intonation and slang is more precise than many Middle Americans she talks to. She will talk to Chris in Detroit. Grandchild of slaves, he wears a carving of the map of Africa around his neck and has been laid off for months. “Yes,” he stammers, voice rough from days of Parliament cigarettes and the worries of the perpetually unemployed, “I’m an American citizen.”

She will talk to Judy in Calgary who will discuss her poor credit rating. Judy once attended a seminar about “the Imposter Syndrome,” a self-help workshop teaching graduate students to self-diagnose their anxieties regarding the place of intellectuals in the neoliberal marketplace. Judy went for the free coffee and muffins. Anything she didn’t have to pay for. Judy will remember inspirational maxims she was force-fed along with crusty baked goods, proclaiming that she is a doctoral student who is confident that she will find a well-paying job. She will stare at the “balance owing” on the screen and say a silent prayer for Judy.

She will talk to John in Brooklyn. With the sound of religious processions carried through the office window, she will yawn silently. It is her night and his day. She will smile into the headset. “Good morning, sir! How are you today?” John will have just told his mother that everything is fine, before carrying empties of beer to the trash bin, kicking aside used syringes, and glancing at the homeless and the hipsters. She will see his prison and hospital records flash on the screen. He will smile into his cell phone. “Yeah, fine thanks.”

“Jen” smiling into a headset is not a trusted friend or confidant. When baptized by a Bank with her new outsourced cheerleader pseudonym, she giggled, as it reminded her of a word in another language meaning ghost. She sees your credit rating, prison and hospital records. She says a silent prayer for America.

We are a world of imposters. The postures of authenticity are continually undercut by the elaborate productions of civility and capital that construct a world of fakes. Abraham in Ethiopia cannot cross the border, but his beans carry the fragrant aromas of coffee down the sparkling Western city streets. The produce is picked by Mexicans, the children fed by a Filipina, and the waiter is from Baghdad. To obtain a UK visa one no longer talks to the British, but to “World Bridge,” a private business that now processes all applications. Heitsi greets you with a thick North American accent and dark hands that clink with wooden bangles. A British flag emblazoned on her chest, she flew through London once on her way to Nigeria. “That’s a crazy airport.” The authenticity of production, the production of authenticity is undercut by stages of capital—assembly line, office banter, Internet wires upon which people stammer and strut.

Ron shortened his Sanskrit name to make it translatable over emails sent to and from Silicon Valley. He crosses the Indian border with a newly purchased Person of Indian Origin card that conceals his grudging disdain for the nation’s poor, and his Lonely Planet accent. Ron skips across electronic sidewalks from New Jersey to New Delhi, the clip of his Italian leather shoes impatiently tapping in border security lines.

Faraz sees India from the rooftops of Pakistan. Delicate Ghazal heard across fault lines of nations resonate with him, like the songs of mothers singing mother tongues. At the border his name is translated into an electronic ledger of suspects and detainees. Curves of prophetic name turns to hard English letters and prison numbers, as unforgiving as passport photos and the harsh lights of shopping malls and interrogators.

The irony of our time perhaps lies in efforts to tighten borders and fix authenticity, while bodies and voices change, exchange, and multiply, leaving little trace or truth of origin. The world is made up of imposters.

—Tara Atluri