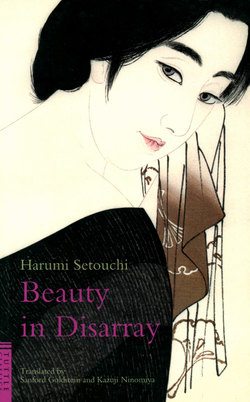

Читать книгу Beauty in Disarray - Harumi Setouchi - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

IT MAY surprise Westerners to realize Japan had its own well-known women's liberation movement in the late nineteenth century, that first feminist movement extending almost to the end of the Taisho era in 1926. Appearing in 1901 was Akiko Yosano's Tangled Hair (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1987), startling readers with its narcissistic and sexually oriented poems and a heroine trapped by society's usual subjugations and restrictions:

In my bath—

Submerged like some graceful lily

At the bottom of a spring,

How beautiful

This body of twenty summers, (poem 16)

Softly I pushed open

That door

We call a mystery,

These full breasts

Held in both my hands, (poem 26)

These scraps of paper

Scribbled with poems

In which I cursed and raved,

I press down hard

On a black butterfly! (poem 53)

Twenty, jealous,

Wilting this summer

In the village heat,

I listen to my husband

Taunt me with Kyoto pleasures! (poem 121)

To punish

Men for their endless sins,

God gave me

This fair skin,

This long black hair! (poem 152)

On September 22 and 23, 1911, when a Japanese translation of Ibsen's A Doll's House was performed in Tokyo at the experimental theatre of the Art Association, Japanese audiences were stunned by the superb performance of Sumako Matsui as she played a Nora who could walk away from her responsibilities as wife and mother. Harumi Setouchi, the author of Beauty in Disarray, quotes the critic Seiseien Ihara:

Sumako Matsui played the heroine Nora. At the opening curtain when she cheerfully came on stage humming, she commanded no attention, her appearance not the least bit like Nora's. But beginning with the moment when she behaved like a spoiled child to her husband Helmer, confided her secret to the widow Mrs. Linde (which suggested Nora's great awakening afterwards), asked her husband to get the widow a job, innocently played hide-and-seek with her children, and finally up to the scene just before the curtain falls when she cries alone on the stage, "It can't be! It's impossible!" and is gradually terror-stricken after she had been told about Krogstad by her husband even while she still thought, "How was it possible for such a thing to happen?" (because she could not believe what Krogstad had told her while he was threatening her), Sumako changed wonderfully and variously, as if the quietness of water had been transformed into the great stirring of multifarious waves. During that interval there was not the slightest slackening in Sumako Matsui's performance, the movement of her facial expressions so intense the audience was completely captivated by the heroine... Above all, despite the fact that I am a man, the scene in which Nora leaves home after her great speech thrilled me because of the adroit cleverness of the play itself (pp. 90-91).

In November of that same year the play was performed at the Imperial Theatre.

Setouchi was eminently qualified to write this historical novel on women's liberation in Japan, which had its roots in sexual politics, socialism, and anarchism, movements in decline following the famous massacre after the Great Kanto Earthquake that devastated Tokyo and neighboring prefectures on September 1, 1923. Among those put to death in the frenzied and prejudicial aftermath of the quake was Noe Ito (1895-1923), the heroine of Beauty in Disarray.

It was Noe Ito's puerile poem "Eastern Strand" that first attracted Setouchi and led her to do research on Noe and her connection to women's liberation. In 1961 Setouchi finished her book on Toshiko Tamura (1884-1945), whose novel Resignation (1911) reflected the consciousness of the "New Woman." It was at that time that Setouchi came across the name of Noe Ito. Actually Setouchi had just begun work on a long novel about another feminist, Kanoko Okamoto (1889-1939), both Kanoko and Toshiko having in their youth worked on the feminist journal Seito (Bluestocking).

The first issue of Seito in September 1911 focused on the marital problems and other difficulties of women. Curious about Seito, Setouchi once again examined its issues. "As a result of this reexamination," writes narrator-Setouchi in Beauty in Disarray, "I was strongly caught up in the blazing enthusiasm and dazzling way of life in which Noe Ito, the youngest member of Seito, spent her youth on the magazine, defended it longer than anyone else did, absorbed from it more than anyone else had, despaired over it more deeply than anyone else, and, finally, using Seito as a springboard, resolutely sundered herself from her past to fling herself against the bosom of her lover Sakae Osugi— all at the risk of her life and for the purpose of love and revolution" (pp. 20-21). What fascinated Setouchi was neither Noe's literary talent nor growth as a person "but the elaborate drama of the lives she was entangled in, the extraordinary intensity of each of the individuals who appeared upon her stage, and the bewitching power of the dissonant play of complexity and disharmony performed by all those caught up in these complicated relationships" (p. 21).

In addition to the life of Noe Ito, Beauty in Disarray has in-depth portraits of Raicho Hiratsuka (1886-1971), Ichiko Kamichika (1888-1981), and Sakae Osugi (1885-1923). Raicho became famous in 1908 as a result of the Baien Incident, when she supposedly planned a double love-suicide with the novelist Sohei Morita (1881-1949), whose later novel Baien (Smoke, 1909) celebrates the affair. In 1911 Raicho and other young unmarried women from the upper classes founded the Seitosha (the Bluestocking Society). Seito, the society's journal, was for women only. Its first number contained Raicho's famous manifesto "In the Beginning Woman was the Sun" (Genshi josei wa taiyō de atta):

In the beginning Woman was the Sun. She was a genuine being.

Now Woman is the Moon. She lives through others and glitters through the mastery of others. She has a pallor like that of the ill.

Now we must restore our hidden Sun (p. 85).

Beauty also contains another Raicho proclamation, one that appeared in the 1914 New Year issue of the famous journal Chuokoron: "I am a New Woman," chanted Raicho. "At least day by day I am endeavoring to really be a New Woman. It is the sun that is truly and eternally new. I am the sun. At least day by day I wish to be and am endeavoring to be the sun..." Continued Raicho: "The New Woman is cursing 'yesterday.' The New Woman can no longer bear to walk silently and submissively along the road of the old-fashioned woman who has been a victim of tyranny" (p. 164).

Another famous personality in the feminist movement was Ichiko Kamichika, who joined the Seitosha in 1912 while a student at Tsuda College. Later when she became a teacher, she was dismissed because of her association with Seito. In 1916 she was a major participant in what became known as the "Hikage Teahouse Incident," in which she stabbed her lover, the anarchist Sakae Osugi. Osugi had fallen in love with Noe and was just beginning to live with her. This event is one of the major dramatic episodes in Beauty in Disarray.

Osugi was the leading anarchist of the Taisho era. His first involvement in a cause was in 1906 when he lent his support to public forces against an increase in Tokyo trolley fares. As a result of this support, he was arrested and imprisoned. It was due only to Osugi's imprisonment in 1908 for another event that he was not implicated in the High Treason Incident of 1910, in which key leftists were executed for a conspiracy to assassinate Emperor Meiji (1852-1912). Osugi's love affairs with Noe Ito and Ichiko Kamichika resulted in his being stabbed by Ichiko, an event that led to a divorce from his wife Yasuko. Later he married Noe. On September 16,1923, while Osugi, Noe, and a nephew were returning home, a police captain arrested the trio. The prisoners were later beaten to death by the captain and his cohorts.

Noe had two children by her first husband Jun Tsuji (1884-1944), the Japanese dadaist, and five children by Osugi. It was Jun Tsuji who had purchased a copy of Seito and given it to Noe the following day. As Noe read Seito, she was inspired by Raicho's emotional manifesto, including the following: "I want, together with all women, to convince myself of the genius that is lying in women. I put my faith only in that one possibility, and I want the heartfelt joy of the happiness which comes from being born into this world as women" (pp. 85-86).

In November 1914 Raicho felt compelled to give up Seito, for family and financial difficulties had caused too much of a strain. Noe, however, decided to take charge of the journal. She was editor from January 1915 until she had to discontinue publication in February 1916.

Beauty in Disarray takes as one of its major subjects the development and growth of Seito. Furthermore, at the very core of the feminist struggle during the Meiji and Taisho eras is the drama of several complicated love triangles, in addition to the anarchist and socialist movements of the time.

The life of Harumi Setouchi has also had its dramatic complications. Born May 15, 1922, she was the second daughter of a craftsman of Shinto and Buddhist altar articles. She entered Tokyo Women's Christian College in 1940, married in 1943, and proceeded to China with her husband. When the war ended in 1945, she returned to Japan, separated from her husband in 1948, and divorced him in Kyoto in 1950. Her return to Tokyo in 1951 found her joining the Bungakusha literary group, its leader Fumio Niwa, the famous writer of fūzoku shōsetsu, novels dealing with modern urban life. Setouchi's biography of pioneer feminist Toshiko Tamura brought her fame as the recipient of the First Toshiko Tamura Prize in 1960. She continued to write biographies of contemporary political and literary feminists as well as biographical novels, the major one being Beauty in Disarray. Japan's literary world was stunned on November 14, 1973, when Setouchi became a Buddhist nun. During a ceremony at the Chusonji temple in Iwate prefecture, she was shorn of her beautiful locks and given the Buddhist name Jakucho. In 1974 she moved from Tokyo to Sagano in Kyoto to live in the Jyakuan hermitage. In 1989 she published a volume of essays entitled The Glory of Women Who Gained Independence (Jiritsu shita onna no eikō). Her energy and public presence remain undiminished. In 1989 she became president of Tsuruga Women's College in Fukui prefecture.

Setouchi remains unique in Japanese literature for her depiction of the struggle of women in love, women in politics, and especially the strong ties women have to the men they love. During the last three decades she has raised the biographical novel to a dynamic art form.

Sanford Goldstein

West Lafayette, Indiana

Kazuji Ninomiya

Niigata, Japan