Читать книгу An Archive of Hope - Harvey Milk - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Harvey Milk’s Political Archive and Archival Politics

CHARLES E. MORRIS III AND JASON EDWARD BLACK

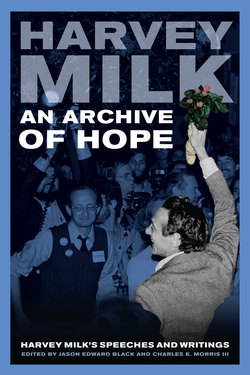

In the Images of America memory book San Francisco’s Castro, there appears a photograph depicting three volunteers anchoring the Harvey Milk Archives (HMA) booth at the 1982 Castro Street Fair.1 Fittingly, the photograph was taken by Danny Nicoletta, Harvey Milk’s protégé and photographer, who, for four decades now, has provided invaluable views of GLBTQ (gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer)2 life in San Francisco. For those who personally remember, or for those who, against the odds, have somehow learned some GLBTQ history, the photograph may be haunting, temporally and tragically poised as it is between the immediate past of Milk’s 1978 assassination and the unfolding present and future of HIV/AIDS in Ronald Reagan’s New Right America. Even so, Milk’s signature hope appears richly embodied in the photo’s details—his huge smile beaming from a displayed portrait; the “Supervisor Harvey Milk” posters; the stack of Randy Shilts’s newly published biography, The Mayor of Castro Street; and volunteer Tommy Buxton’s laugh, implying a joyous carnivalesque occasion, communion, reprieve—suggesting that public memory powerfully affords comfort, community, and politics.

Like those HMA volunteers on Castro Street, we hope in this book to deepen and circulate the public memory of Harvey Milk. During the 1970s, Milk passionately lived as an activist and visionary, community builder, and stalwart and savvy campaigner, one of the first openly gay political officials in the United States. And Harvey Milk died with his boots on, a martyr—if not at the moment of his death, as some will quibble, then surely at the pronouncement of the unjust, undoubtedly homophobic verdict in his assassin’s trial. Public memory is fraught, mutable, forceful, and consequential, and we believe it can be transformative in the lives of GLBTQ people—and everyone. What Harvey Milk bequeaths in the pages that follow is An Archive of Hope.

REMEMBERING HARVEY MILK

If you knew and loved Harvey, as so many in San Francisco still did, especially in those first years after his death, you likely took heart and pride in those enthusiastic efforts to kindle his legacy. Perhaps you donated money to the HMA that day in 1982 on Castro Street. Or perhaps you participated in one of the many Milk memorial events that occurred in San Francisco and elsewhere in recent years: traveling aboard the “Gay Freedom Train” en route to “Avenge Harvey Milk!” at the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in October 19793; attending exhibits at the Gay Community Center and Castro Street Fair in 1979; watching photographer Crawford Barton’s slide show at the Harvey Milk Gay Democratic Club (HMGDC) annual Milk dinner in May 1980; browsing archival materials that accompanied the newly rededicated Harvey Milk/Eureka Valley Library in May 1981; reminiscing at the HMGDC Milk slide show and cocktail party in City Hall that same month; joining devoted throngs in the annual Milk/Moscone Memorial March; standing in line at Randy Shilts’s book signings in 1982; or celebrating at Harvey’s annual birthday party on Castro Street—a bounty of Milk memory!

So much commemoration in those early years of Milk’s afterlives, in fact, that you might have thought Frank Robinson, Milk’s speechwriter and campaign advisor (named as one of only four potential successors in Milk’s political will), was unnecessarily concerned when he fretted in the inaugural 1983 issue of The Harvey Milk Archives Newsletter: “I do not know what Harvey’s fate would have been if the Harvey Milk Archives had not been established. I am not sure what historians would have done, how they might have edited his speeches, how they might have subtly reshaped the past, how they might have interpreted the man who was the man who might have been.”4

Robinson’s insightful words should not be misunderstood as sentimental hero worship or hagiography. Archival materials and their consignation matter, always and profoundly, for histories and memories to survive and thrive, especially for those histories and memories that malignant individuals and institutions would readily consign to oblivion, and for those people who struggle for many reasons against manifold constraints to preserve and promulgate the past. Certainly this is true for GLBTQ histories and memories. Heather Love has written,

The queer past has long served a crucial role in the making of queer community. . . . The desires that queers have invested in the past have transformed it. There are, as a result, many queer pasts: Some versions glitter with the collective fantasies of greatness; others have been rubbed smooth by constant handling; some are obscure, having been forgotten or put away; other versions of the past have been rendered ghostly through the weight of accreted longing; and some are covered by shadows, forgotten traces of ways of life that many would rather leave behind.5

There are, we believe, many queer pasts in Harvey Milk, as varied and valuable, as vulnerable, as those pasts Love describes and Robinson cherishes. The Milk archive, in whatever forms it exists and may eventually take, should never be taken for granted.

The extensive, largely behind-the-scenes efforts during the 1980s and 1990s to amass and preserve Harvey Milk’s words, images, and ephemera deserve greater visibility. Scott Smith, heir and executor of Milk’s estate, who, during their years as lovers, business partners, campaigners, and confidants, had done more than perhaps any other to influence Milk’s transformation into the activist he became, devoted himself to cultivating and protecting Milk’s legacy. He had help, too, from longtime friends and loyal supporters such as Frank Robinson, Danny Nicoletta, Anne Kronenberg, Jim Gordon, Linda Alband, Terry Henderling, Jim Rivaldo, Dick Pabich, Harry Britt, Denton Smith, Wayne Friday, Walter Caplan, John Wahl, John Ryckman, Alan Baird, Rich Nichols, Tom Randol, and Bob Ross, among others. After Scott Smith died in February 1995, some of those friends and associates contributed, culled, sorted, and inventoried materials in preparation for donation by Elva Smith, Scott’s mother, to the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL). Correspondence suggests that negotiations among Elva Smith; co-executor Frank Robinson and the Ad Hoc Milk Archives Committee; and Jim Van Buskirk, Director of the James C. Hormel Gay and Lesbian Center at the SFPL, did not always proceed smoothly. Robinson’s Letter to the Editor of the San Francisco Bay Guardian in July 1995 offers a sense of these archival politics: “Political regimes change, so do library personnel, and the intent of the ad hoc group is to make sure that the Archives will be protected for the use and benefit of future generations.”6 Nevertheless, The Harvey Milk Archives-Scott Smith Collection was officially donated to the SFPL in 1995 and transferred to the library in 1997.7 It opened to the public in 2003.

Although for us this volume has been an enriching venture in GLBTQ memory work, which we hope readers will share, we should emphasize from the beginning that what we exhibit and narrate here—a substantial sample of transcribed documentary holdings representing Milk’s typed, handwritten, recorded, and/or published words—constitutes but a fraction of Milk’s public discourse. Many of Milk’s speeches and writings have been lost because they were originally performed extemporaneously or published in outlets now remote; some of that corpus remains extant if as yet fully extracted in other archives and libraries, such as in microfilm series holdings of GLBTQ periodicals, objects, and documents housed at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco or the ONE Institute in Los Angeles, or materials in private collections. Despite Milk’s presentiments of early death and his poignant foresight to tape-record a political will, he evidently was not much concerned with preserving or organizing his own archive for posterity; the state of his effects and affairs might fairly be described as chronically disheveled, a casualty of a devotedly engaged public life. We have decided to predominantly feature, with just a handful of exceptions, documentary texts of Milk’s public political rhetoric derived from the Harvey Milk Archives-Scott Smith Collection at SFPL because of the concentration and diversity, history, and symbolism of this archival cache. However, we have been keenly aware from the start of this project, and cumulatively so throughout its production, that the Milk materials at the SFPL, invaluable for what they do contribute to Milk and GLBTQ history and memory, are nevertheless incomplete and should and undoubtedly will be beneficially complemented and supplemented in the future.8

It is also the case, as these selected documents evidence, that the traces of Harvey Milk’s actual public discourse—scribbled or typed, scratched out, stump recycled, always in motion—bear the marks of having been lived rather than packaged. Milk’s words are sometimes fragmentary, typically unpolished, and occasionally banal. At the same time, they always crackle with his energetic engagement. We might usefully think of these addresses, columns, statements, press releases, fliers, and open letters as quotidian translations from a single emergently public life; a locally situated if nationally aspirant gay street activist, consummate politician, and municipal official; a gay, white, Jewish, able-bodied, financially strapped but middle-class man. These words are embedded in complex, multitudinous, and intersectional contexts that enabled or thwarted Harvey Milk’s presence, resonance, meaning, and influence in the 1970s, in the United States, in California, in San Francisco, in District 5, and in the Castro. We view such incomplete, tantalizing traces and echoes of distant times and larger stories, both inspirational and workaday texts, as rich enactments of Milk memory. As importantly, they constitute invitations to conversation, debate, reflection, teaching, learning, collaboration, community building, inter-generational relationships, and coalitional and oppositional politics—“how publics are formed in and through cultural archives”9—that inspire performative repertoires10 of GLBTQ pasts that will be queerly reconfigured as the future unpredictably unfolds.

We also have usefully come to realize that some fairly will ask, “Why Harvey Milk?” Not everyone, then or now, considers Milk a pioneer, an icon, as he himself did, remarking to the Associated Press about his election in November, 1977: “I can really appreciate what Jackie Robinson was up against. . . . Every black youth in the country was looking up to him. . . . He was a symbol to all of them. In the same way, I am a symbol of hope to gays and all minorities.”11 Immodesty aside, Milk’s claim on the GLBTQ pantheon might be rebuffed, or at least cause some bristling, despite his progressive populism and multi-issue advocacy, electoral success, visibility, assassination.12 As some have argued, Milk was, after all, a local politician who served less than a year in municipal office, and we will never know what he might have accomplished politically had he lived.13 Many in San Francisco thought him an arriviste. Drummer editor Jack Fritscher remembered that Milk was not well liked by many because he was “a political carpetbagger, because he was Manhattanizing laid-back San Francisco. He wasn’t particularly cool. He was a New Yorker telling ‘The City That Knows How’ what to do in his ‘Milk Forum’ column in the Bay Area Reporter.”14 Many inside and outside of San Francisco, such as Minnesota activist Stephen Endean, who would go on to direct the Gay Rights National Lobby and founded the Human Rights Campaign Fund, despised “Milk’s manner—his ego, his abrasiveness, his insistence on doing things his way—[which] ground on Endean’s Midwestern sensibilities, and also probably on his insecurities.”15

There are also perspectives that help us account for Milk’s legacy in relation to broader cultural and political contexts. Fritscher offers gay immigration, single-issue voting, and assassination as crucial factors: “He was elected because he was gay, not because he was ‘Harvey Milk.’ . . . Beyond even Harvey’s control, he was swept up in a symbolic role in ritual politics. The convergence of his times, not his life, propelled him. His latter-day sainthood came through a martyrdom that could have happened to anyone playing the role of gay supervisor. It was his bad fortune that ‘Tonight the role of gay supervisor will be played by Harvey Milk.’”16 Historian Jonathan Bell more generally links historical visibility with place and contingent circumstance, observing that San Francisco’s attention is chiefly attributable to “the flamboyance and media-consciousness of its politicians and its importance as a microcosm of the social movements that have come to form the bedrock of the rights revolution of recent times.”17 From these vantages, Milk’s posthumous renown should be understood as a complex production of his accomplishments, the where and when of his public life, the volume of his persona, and his dramatic demise.

These challenges and contextualizations are important and should shape any engagement with Milk’s memory. We believe that they usefully complicate, but do not disqualify, a claim of Harvey Milk’s significance, the value of his assembled words. Arguably, what materially matters most in GLBTQ worldmaking, then and now, occurs locally, whatever broader sweep and circulation a figure or place or event might foment or by happenstance occasion in the aftermath of activism. Most courageous GLBTQ activists since the first stirrings of political consciousness, during the arduous history of transformative acts and soundings, made a difference in particular spaces and sites, communities and forums, even as news of what they did—or they themselves—may have traveled. Milk remarked in 1978, “History is made by events . . . sometimes by large events with the world watching, but mostly by small events which plant the seeds of change. A reading of the Declaration of Independence on the steps of a building is widely covered. The events that started the American Revolution were the meetings in homes, pubs, on street corners.”18 Milk’s successor on the Board of Supervisors, Harry Britt, came to a similar conclusion about his political fecundity:

History will betray his own sense of who he was if we only remember him as a charismatic genius, a tragic figure wearing the face of a clown, a bigger-than-life model for gay pride. He was all that, of course, but the specialness of Harvey Milk was to be understood in terms of the specialness of San Francisco in the ‘70s and of the people whose hopes and dreams he was to take upon himself. . . . He could not have been what he was in an earlier period, or in another place. Most specifically, Harvey was a leader whose destiny was the destiny of Castro’s Street People, a motley gang of alienated refugees from the struggle to assimilate to the homophobic mainstream of American life.19

Thus a world of difference might be found in those local queer details called Milk, sine qua non inestimable.

Harvey Milk’s words, too, teach us that successful activists speak locally, that the art of activist eloquence should be measured by the singularity of each ordinary persuasive opportunity, quotidian audience, or fleeting performance. Milk’s purple passages and stump clichés teach us that hope’s discourse, at close hearing by real people, is by turns and toil both sublime and hackneyed in situ. And with each of those hit-or-miss moments of rhetorical invention and embodiment, with each handshake, with each overbearing exchange, shameless self-promotion, flirtation, corny joke, and lump-in-the-throat moment when he was on a roll, Milk brought the GLBTQ folk of San Francisco that much closer to sexual justice and freedom, to gay rights. Milk campaign staffer Jim Rivaldo remembered, “I accompanied Harvey around the city and saw how readily people from all walks of life responded to an openly gay man with good ideas and an extraordinary gift for communicating them.”20

Of course Britt’s reminiscence—and he is not alone in this—elevates Milk onto a larger stage. Such hyperbole should not surprise or trouble us, as it is the currency and glue of public memory and social movements, both always replete with the propulsive lore of gods and devils.21 Additionally, close associates of those inscribed into history and memory are often prone to flattering exaggeration. While wanting to avoid the distancing and distortion that comes with hagiography, we nevertheless believe Milk earned his inscription and our attention in GLBTQ history and memory by his contributions to gay rights writ large. Like GLBTQ activism itself during the 1970s, Milk was increasingly emerging on a national stage, with expanding influence. During the spectacular historic fluctuations of GLBTQ fortunes during 1977, Milk proved himself a movement leader and subject of national press coverage. Rodger Streitmatter, in spirit if not letter, conveys Milk’s growing reputation and influence: “If San Francisco was the capital of Gay America, Harvey Milk was president.”22

In a 1978 interview, Boze Hadleigh asked Milk, “As the most visible gay politician, aren’t you going to be in demand as a national spokesperson?” His response: “That’s starting already. A few groups have asked . . . but I’m so busy as it is, there’s no time.”23 Nevertheless, during those few last months alive and working, Milk, along with tireless and talented activists Sally Miller Gearhart, Gwen Craig, Bill Kraus and so many others, led the successful statewide campaign to defeat Prop 6, called the “Briggs Amendment” after its sponsor, state assemblyman John Briggs, which would ban gay teachers from the California school system. Clendinen and Nagourney explain, “The decisive defeat of the Briggs initiative on November 7 [1978] was the greatest electoral victory the gay rights movement in the United States had known. It conferred a particular aura of historical celebrity on Harvey Milk, and at the victory party in San Francisco that night, he called for a gay march on Washington in 1979.”24 Assassinated 20 days later, Milk’s place in the 1979 March for Lesbian and Gay Rights would be memorial, and thereafter sorting out and celebrating the historical contributions of the sanctified leader would be inevitably enhanced and muddled by the tropes of remembered martyrdom. The Chicago Tribune reported on November 30, 1978: “Milk, the leading avowed homosexual politician in California and perhaps the nation, will be especially missed. . . . ‘Harvey Milk’s assassination is a terrible blow to the gay-rights movement in this country,’ said Robert McQueen, editor of The Advocate, San Francisco’s leading gay newspaper. . . . [S]aid Harry Britt, one of Milk’s closest friends and aides, ‘Harvey Milk was the Martin Luther King of this nation’s gay-liberation movement.’”25

Perhaps Ed Jackson was most insightful in capturing Milk’s hold on the historical imagination when, in his 1984 review of Rob Epstein’s documentary, he wrote, “The Times of Harvey Milk works powerfully on the viewer because of the Camelot-like resonances it sets off. On one level the story of one man’s political career, it is also a morality tale about the dream of justice and the American faith in electoral politics. It traces the evolution of a populist hero who came to embody the hopes of an entire community, a hero tragically cut down in the prime of his political life.”26 Whatever the measure, on the street or on the pedestal, we believe Harvey Milk is historically significant, worthy of archiving and anthologizing, deserving of memory, and most importantly, accessible and relevant for cultural and political purposes in which he can prove invigorating and troubling still, and perhaps lifesaving.

HARVEY MILK: A BRIEF POLITICAL GENEALOGY

Given that Harvey Milk’s public life did not begin until he was in his forties, and once begun lasted less than a decade—only ten months, eighteen days in office—it is a wonder that we should be bequeathed this archive. Indeed, it is a wonder such a public life began at all. Milk was not what most would consider destined for activism and politics. For most of his adult life Milk lived a quietly privileged domestic existence, passionately and monogamously devoted to his “marriages,” his home, the opera, and other arts in New York. Though in retrospect some might consider him closeted, which is not quite the case, it is fair to say that Milk’s private life was compartmentalized. His professional choices—in the Navy, as a schoolteacher, and for years in the financial world—reflected and no doubt solidified this conservatism. To the extent that he was political at all, as chroniclers like to recall, Milk had proven himself to be a Goldwater Republican. One can imagine those who knew Milk during most of life, those unaware of his sexuality but also his former lover Joe Campbell, doing a double take as he began making headlines in, of all places, San Francisco.27

Milk had made one other dramatic transformation prior to emerging as the “Mayor of Castro Street,” and this may make it difficult to fathom Milk as the formidable politician he would become. Owing to the times, a young lover named Jack McKinley, and an experimental theater visionary named Tom O’Horgan (Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar, and Lenny), Milk had become a hippie. As Randy Shilts described it, “Milk found himself surrounded by some of the most outrageous flower children on the continent. Harvey started assimilating the new countercultural values, which spurned materialism, eschewed conformity, and mocked orthodoxy. With each month, Milk’s hair became a little longer. With each political argument, his views became more flexible. With each new apartment, he discarded more of the tasteful furniture, stylish décor, and middle-class comforts he had cherished.”28 While briefly living in San Francisco in 1970, this Wall Street suit memorably burned his BankAmericard in response to the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. Two years later, with a new boyfriend named Scott Smith, Milk returned to California, flowers in his hair, roaming the state until finally settling for good in 1973 into a transitional neighborhood known by locals as Most Holy Redeemer Parish—what would become known as Castro Village and then, as now, the Castro.

Something queer was happening in San Francisco; indeed, it had been going on for quite some time. Always a haven for outsiders, San Francisco since World War II had become home to a sizeable population of GLBTQ people. Though more familiar for its 1970s blossoming, and overshadowed by mythic Stonewall, San Francisco should be remembered well for its much longer history of GLBTQ lives, cultures, and politics. In the 1950s Hal Call formed a chapter of the Mattachine Society, and Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon founded the Daughters of Bilitis, making the city a stronghold of homophile outreach. Jose Sarria, a drag institution at The Black Cat, who had tirelessly and resiliently stood up for his harassed, arrested, and beaten brothers, ran for Board of Supervisors in 1961, amassing 7,000 votes more than a decade before Milk’s audacious first political campaign. Sarria’s voice sounded the clarion call of a developing movement comprised of the organizations formed during that decade, including the League for Civil Education, Tavern Guild, Society for Individual Rights, and the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH). The protest press conference held by the CRH in response to shameful police disruption of the New Year’s Day Ball in 1965, as well as the trans people and other queers who resisted police brutality at Compton’s Cafeteria in August 1966, stand alongside Stonewall as transformative events in the burgeoning national movement for GLBTQ liberation, rights, and pride. California establishment politicians were already responding to these grassroots activists in the nascent politics for sexual justice before the New York “birth” of liberation on Christopher Street in 1969.29

What GLBTQ San Francisco had been through the 1960s, though significant, would not have necessarily led one to predict the massive influx of immigrants and the expansion of cultures and politics in the subsequent decade.30 John D’Emilio observes, “By the mid-1970s San Francisco had become, compared to the rest of the country, a liberated zone for lesbians and gay men.”31 Such growth was enabled by changing economic and demographic landscape of the city. San Francisco’s transformation from a manufacturing center into a metropolis of corporate headquarters, tourism, and conventions, depleted the population’s blue-collar, straight families in the many ethnic neighborhoods; consequently, it also enticed young professionals who found inexpensive housing in places like the Castro. Development politics were fraught, and tensions flared throughout the 1970s and beyond, inside and outside GLBTQ communities.32 With San Francisco’s development, however, accompanied by a growing reputation for sexual freedom, a GLBTQ homeland blossomed. D’Emilio explains that communities rapidly grew in a number of neighborhoods—Castro, Polk Street, Tenderloin, South of Market, Folsom Street, Upper Mission and Bernal Heights—constituting a “new social phenomenon, residential areas that were visibly gay in composition.”33

With such visibility came more immigrants, social and sexual networks and spaces, communications, businesses, civic groups, political organizations, movement mobilization and action, public festivals, and celebrations. Reporting on the “economic boom” and “political clout” of GLBTQ San Francisco during the 1970s, the Washington Post concluded that it was the “most open of any [homosexual community] in the nation.” Frances FitzGerald described the Castro as the “imminent realization” of gay liberation, “the first gay settlement, the first true gay ‘community,’ and as such it was a laboratory for the movement. It served as a refuge for gay men, and a place where they could remake their lives; now it was to become a model for the new society—’a gay Israel,’ as someone once put it.” Danny Nicoletta’s recollection is equally effusive: “Into the Seventies, people arrived in San Francisco from all over the world with hopes of creating a life characterized by the consciousness attributed to the Sixties communal, holistic, non-violent, mystical, theatrical, and avant-garde. A facet of this idealism for myself and many others was that we were people who were gay searching for a place to be open and honest about this part of our lives—a place without fear of the hatred and persecution which had kept us in closets for so long.”34

With such concentration, circulation, capital, and confidence, GLBTQ people also developed politically. The San Francisco Chronicle reported on its front page in 1971, “San Francisco’s populous homosexual community, historically nonpolitical and inward looking, is in the midst of assembling a potentially powerful political machine.”35 With the first gay rights marches, creation of the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club, Jim Foster’s path-breaking speech at the Democratic National Convention in 1972, and thriving lesbian-feminist communities, one might readily have believed the Chronicle’s hyperbole, which became all the more manifest as the decade unfolded. Jonathan Bell’s incisive analysis demonstrates that a broader confluence of contextual elements in California politics dating back more than a decade enabled such queer auspiciousness. From Bell’s perspective, left liberalism guided a generation of influential and ascending politicians who fused economic and civil rights in a progressive vision of inclusion; politicians who were influenced by and collaborated with grassroots activists and who helped create the conditions under which such disenfranchised groups could make gains through electoral politics. This is not to say that Willie Brown, George Moscone, Phil Burton, Dianne Feinstein, Richard Hongisto, and other key political players of the era were unfettered champions of or exclusively responsible for gay rights, as Harvey Milk’s critiques of superficial campaign courtship and battles with “the Machine” would later demonstrate. However, this analysis does help explain the conditions of possibility, “the distinctive contours of political life in San Francisco in the 1970s,” within and through which Milk could emerge, mature, and ultimately succeed as a gay rights and community activist with a populist vision articulated through the discourses of economic justice, individual rights, political power, solidarity, and coalition.36

But of course it was not only because San Francisco existed as the “political base” and “spiritual home of California liberalism” that GLBTQ people flourished.37 The intensifying, intensely satisfying, and interanimating dimensions of cultures and politics forged identification and identity, cultivated emotional bonds, deepened communities, fomented movement, and resulted in the sexual embodiment of freedom. Especially for gay men, such freedom was made all the more available and fluid by proliferating and booming bars, bathhouses, and clubs. With such growth came inevitable tensions, and there have been critiques, for example, of the gay male sexual culture.38 However, sociologist Elizabeth Armstrong argues persuasively that those committed to gay rights (interest group politics and legal protections), gay pride (cultural identity and visibility), and sexual pleasure (its enactment and commercialization) created a synergistic movement of “unity through diversity.”39 Armstrong observes, “The political logic of identity made it possible to reconcile pride, rights, and sexual expression,”40 despite differences among and the uniqueness of individuals, that solidified in economic power, political influence, and a sense of the collective instantiated through pleasure.

Significant, too, is the still broader context of national culture and politics, as well as the larger gay rights movement. Bruce Schulman writes in The Seventies, “[T]he emphasis on diversity, on cultural autonomy and difference, echoed throughout 1970s America. White ethnics picked it up, as did feminists and gay rights advocates and even the elderly. A new conception of the public arena emerged.”41 Contrary to narratives about cultural reversals and moribund activism, Dominic Sandbrook argues, “For all the efforts of the religious right and for all the talk of backlash against the legacy of the sixties, the fact remains that in moral and cultural terms, American society became steadily more permissive. More marriages broke up, more pregnancies were terminated, more children were born out of wedlock, and more gays and lesbians came out. In this respect at least, liberalism not only survived the 1970s but emerged triumphant.”42 Moreover, GLBTQ activism in particular should be understood as not only a legacy of the “long sixties” but as a distinctive influence on U.S. culture. Schulman goes so far as to conclude, “The gay rights movement transformed Americans’ understanding of homosexuality, and of masculinity in general” elsewhere he wrote, “Looking back . . . it is clear that the grassroots struggles for racial justice and sexual equality have exerted a more thoroughgoing impact than the liberal political economy of the Great Society.”43

Such superlative assessments are warranted by hard-earned achievements of GLBTQ people and organizations, and the widening visibility that came with them. The often-cited Time cover story, “Gays on the March,” from September 1975, remarked on the transformation:

There are now more than 800 gay groups in the U.S., most of them pressing for state or local reforms. The Advocate, a largely political biweekly tabloid for gays, has a nationwide circulation of 60,000, and the National Gay Task Force has a membership of 2,200. . . . Since homosexuals began to organize for political action six years ago, they have achieved a substantial number of victories. Eleven state legislatures have followed Illinois in repealing their anti-sodomy laws. The American Psychiatric Association has stopped listing homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder, and AT&T, several other big corporations and the Civil Service Commission have announced their willingness to hire openly avowed gays.44

Little wonder, then, that even as the movement shifted from the brief revolution of gay liberation to the mainstay of gay rights reform (growing in numbers while contracting its agenda to single-issue politics), a heady mood of historic transformation pervaded. Like other GLBTQ people, John D’Emilio, himself both chronicler and activist, rode high on the collective effervescence: “The goals of activists had narrowed, yet activists in the mid-1970s almost uniformly displayed an élan that made them feel as if they were mounting the barricades. Activists increasingly engaged in routinized and mundane organizational tasks, yet they believed they were remaking the world.”45

Harvey Milk emerged from within these layered political and cultural contexts, reflecting them but also, improbably, harnessing their energies and promises into a unique activist vision that would help define the rest of decade, locally and nationally, as an epoch in GLBTQ history. Of course, Milk did not commence his political career as the leader he would become. He began it quite sparsely and unremarkably in the spring of 1973 in his newly opened Castro Camera at 575 Castro Street. The always threadbare business, which kept Milk in the financial straits to which he had not been accustomed during his earlier life, seems destined to the storied political front and headquarters it became. The real work of Castro Camera and its regulars focused not on rolls of film but on people, their freedoms, struggles, and neighborhoods in San Francisco.

Although Milk’s deeper political inclinations may be attributable, by his own accounting, to the 1943 Jewish uprising in the Warsaw ghetto and his 1947 arrest as a teenager in Central Park for “indecent exposure,” Milk often identified three moral shocks46 in 1973 as effecting his awakening and sparking his first campaign for Board of Supervisors, the eleven-member body representing San Francisco’s consolidated city-county government. First, shortly after Castro Camera opened, Milk had a heated altercation with a local bureaucrat who demanded a $100 deposit against sales tax in order for the business to operate, which seemed to him an outrageous violation of free enterprise and symptom of class inequity. Second, Milk blanched at the disparity between haves and have-nots in this “developing” city, disparity which appeared proximately in the form of a young teacher from a resource-strapped school asking if she could borrow a slide projector to teach her lessons. Finally, Milk had a visceral response to Attorney General John Mitchell’s mendacious and evasive testimony during the Watergate Hearings, which he watched animatedly on a portable TV in the shop. Shortly thereafter, standing on a crate inscribed with the word “soap,” Milk launched his first candidacy.47

A more auspicious political debut, short of winning, is hard to imagine. Perhaps especially so given the long odds Harvey Milk faced as an unknown newcomer, both to the city and to politics, with the wrong look and surprisingly fierce opposition. For starters, there was that ponytail few could ignore, the signature symbol of his troubling hippie persona. Milk was also openly and unabashedly gay, which, needless to say, for an at-large candidate in a citywide election battling five incumbents, made for a political liability.48 We should recall and underscore how few GLBTQ candidates preceded Milk on any ballot in the United States, so few in fact, and with decidedly less candor and bravado, that it is not surprising (mythmaking notwithstanding) that he is often mistakenly celebrated as the first.

What may come as a surprise, however, is that Milk’s gay problem mostly concerned GLBTQ people themselves, or as Brett Callis observes, “His candidacy was itself a major issue for gays in 1973.”49 There was much passionate dispute in the GLBTQ press, social spaces, and political meetings, about how GLBTQ politics should proceed into or against the mainstream. Should the approach be accommodationist or radical? Should GLBTQ people enter politics to gain power or rely on the stewardship and largesse of straight allies? Should candidates make sexuality their defining marker, or should their ideology and platform take primacy over the fact that they happen to be gay? What might public engagement mean in relation to a politics of respectability? Should candidates be single-issue focused on gay rights or be committed to a broad set of issues?

From the beginning of his campaign, Milk was adversely targeted by the gay political establishment—the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) and the Toklas Club—whose key players and gatekeepers, by and large, had their own scars and believed in an accommodationist and gradualist approach to gay rights, gained through loyal support of elected straight liberal allies, what Milk derisively would later call the “gay groupie syndrome.”50 Michael Wong, a young, heterosexual, Chinese American who, in launching his own political career, courted counsel and support of prominent members of the Toklas Club, captured well in his diary this attempted fratricide by powerful members of the gay establishment:

Gary Miller told me that Harvey Milk was “dangerous and uncontrollable.” Duke Smith said that Harvey Milk was “high on something.” Rick Stokes told me that Milk “had no support in [the] Gay Community . . . he’s running all on his own.” Jo Daly told me, “Maybe if we just ignore him, he’ll go away.” Jim Foster said that “it would be disastrous for the gay community if Harvey Milk ever received credibility.” I couldn’t have agreed with them more.51

Heeding such advice, Wong helped to block endorsements for Milk with San Francisco Young Democrats and San Francisco Tomorrow. Foster in particular, perhaps the most visible and influential gay establishment politician in San Francisco, openly opposed Milk until the bitter end, even after Milk had won over the Bay Area Reporter, SIR leader and Vector editor William Beardemphl, other publications, and a critical mass of GLBTQ voters.52

The intensity of the vitriol by Milk’s political enemies within the GLBTQ community suggests that they saw in him something more than an upstart of questionable motives and dubious emotional stability. Wong wrote privately what insiders would not admit: “No candidate came close to his dynamic delivery. . . . He stole the show. . . . [Everywhere he spoke, people were drawn to him. He was not slick and people related to him. He was causing the Toklas Club great concerns.”53 Moreover, Shilts astutely observed, “The disparity between Milk’s image and his reality stemmed from the essential act with which he defined himself—rebellion. The campaign biography that emerged from his early media interviews reads like the blueprint for a maverick.”54

And a queer, barnstorming, populist maverick he was. Milk’s broad platform focused on a wide range of issues that prioritized San Francisco residents over the city’s corporate and Chamber of Commerce interests. As the selected documents from 1973 reveal, Milk envisioned San Francisco as a city that would take its place among other great metropolises not for its bankbook or universities but for its populace, “a city that breathes, one that is alive and where the people are more important than the highways.” Instead of downtown development and growth of the tourism industry, for Milk San Francisco’s future depended on reducing wasteful and unfair governmental spending and taxation, promoting childcare centers and dental care for the elderly, eliminating poverty and addressing the unemployment rate by teaching skills and providing economic opportunities. Instead of fringe benefits for MUNI (San Francisco Municipal Railway) drivers, Milk advocated better service for MUNI riders, which would be achieved in part by mandating that city officials ride MUNI to work, and preventing congestion by reducing downtown parking garages. Instead of police harassment and arrests for marijuana possession, prostitution, and gay public sex, what he called “legislating morality” against “victimless crimes,” Milk demanded improved police protection against rape, murder, and mugging, which would be achieved if policemen actually lived in the city they patrolled, and patrolled in greater numbers. As he argued in his September 1973 address to the Joint International Longshoremen & Warehousemen’s Union and Lafayette Club, “It takes no compromising to give the people their rights . . . it takes no money to respect the individual. It takes no political deal to give people freedom. It takes no survey to remove repression.” From promoting street arts and community art centers, to advocating for beer drivers’ Local 888, to the district elections (Proposition K) he championed, Milk imagined the end of disenfranchisement and discrimination, better quality of life, and resurgence of democracy for all.

That Milk had indeed made a statement during the campaign is evidenced by the nearly 17,000 votes he garnered, finishing tenth in a field of thirty-two candidates. More heartening still, Milk realized that had there been district elections, voters in San Francisco’s GLBTQ neighborhoods, despite the Toklas Club’s opposition, would have delivered him to City Hall. SIR official and Vector editor William Beardemphl presciently observed in his Bay Area Reporter “Comments” column that, “Above and beyond his race for Supervisor, Harvey Milk IS opening the door to government a little wider so that all homosexuals of ability can enter politics without a destructive homosexual stigmata imposed on them.”55 Milk appears to have been emboldened by the experience and results, for he almost immediately cast his sights on the 1975 campaign and during the interim would become an even more dedicated and visible community and gay rights activist. During this period, Milk’s political vision solidified and public voice amplified more prominently as he launched biweekly columns for the Sentinel (“Waves from the Left,” February to September 1974) and Bay Area Reporter (“Milk Forum,” May 1974 until the week of his death, November 1978) and regularly took to the streets in protest against homophobic discrimination, harassment, and violence, or in celebration of and communion with his GLBTQ neighbors, friends, and allies.

During 1974 and 1975, Milk continued his broad-based populism, but he also unmistakably sought to mobilize his own community toward seizing and consolidating its power through strength in numbers, solidarity, votes, and economic influence. In his effort at consciousness raising, Milk implored GLBTQ people that “the only important issue for homosexuals is Freedom. All else is meaningless. . . . Many people think that they are FREE because they have a lot of money and live in ‘good’ neighborhoods. But the homosexual is not free until there are NO laws on ANY books suppressing him and not until he, if he so wishes, can join the police force or any government agency as an open homosexual. It is as simple as that.”56 In his Vector editorial, among the selected documents, Milk invoked Martin Luther King, Jr., and memories of the Montgomery bus boycott to punctuate his call for “full citizenship” and struggle against homophobia: “the homosexual community is the last minority group that has received no civil rights. . . . In order for homosexuals to win our right to self-respect and equality, we must first assert our full existence and then its strength.”

Once awakened, according to Milk’s political calculus, GLBTQ people must act collectively to concentrate and strategically wield their power, which he theorized in economic, political, and communal terms. Milk’s “Waves from the Left” column in the Sentinel on “Political Power,” included in this volume, emphasized that change only comes through the exercise of material influence. That power begins with registering to vote, which is why Milk appropriated diverse occasions for that purpose and enlisted as many volunteers as he could muster (always recruiting) to help with drives (2,000 new voters for the 1974 gubernatorial election and many more for his own campaign in 1975). For those registered, Milk urged that political power works best in withholding votes until a sense of urgency among “friendly” candidates leverages sturdier pledges rather than automatically or prematurely offering votes for the price of a trivial campaign courting appearance.57 Milk lashed out at his gay establishment nemeses for being what he called, in the selected editorial of the same name, “Aunt Marys,” the equivalent of Uncle Toms, who sold out by toadying to straight liberal politicians who forgot their GLBTQ constituents once elected. Then GLBTQ voters should cast their ballots as a bloc, the sheer size of which would likely determine the outcomes of elections, making the community’s presence unmistakable and influence palpable and in turn, quid pro quo, desirable capital. During 1974, Milk also began his practice of publishing endorsements, and disqualifications, with detailed political analysis specific to communal interests. Milk declared, “Every person in this state owes it not only to himself, but for all gay people who will follow us years from now[,] to vote for freedom.”58

Second, Milk insisted, “Economic power is stronger than any other form of power. . . . There is tremendous amount of economic power and strength in the San Francisco gay community. It has never been effectively brought together. It looks as if it will now happen.”59 Milk’s optimism stemmed from those existing and emerging associations—Gay Chamber of Commerce, Gay Community Guild, Tavern Guild, and Golden Gate Business Association—he supported, and the Castro Village Association he founded, which welcomed 5,000 for its first Castro Street Fair in August 1974 (25,000 in 1975, 100,000 in 1976).60

Third, Milk advocated the power of solidarity and coalition. He argued that GLBTQ people and politicians must eradicate endemic jealously and infighting; otherwise, such divisions amounted to complicity in their own oppression. In the Bay Area Reporter, Milk averred, “The day we can pick up a gay paper and not find any attacks on other gays, the movement will start to unite. It can never have full power as long as one person, for whatever reasons, attacks others in the movement . . . to go after another gay person for their doing their trip in the movement, is to attack the entire movement.”61 He convened a task force to explore paths to unification. Milk also urged the support of the Teamsters in the Coors Boycott as well as other unions, reasoning, “If we in the gay community want others to help us in our fight to end discrimination, we must help others in their fights.”62 About the neighborhood baseball challenge between the “gay all stars” and “champs of the local Twilight League,” Milk effused, “Just the playing of the game did more to bring relations between the community than any other event, act, speech, law. . . . That game was a victory for better relationships between the straight youths and the gays.”63

Beyond this communal power vision, Milk also became bolder in his confrontation with individuals and institutions harming GLBTQ people and other San Franciscans. Milk lambasted the city government for giving taxpaying members of the Gay Freedom Day Committee the “run-a-round” regarding permits and parade routes (but not other similar groups),64 and in his Open Letter included in the volume, chided the San Francisco Chronicle for sensationalizing gay pride without sensitivity to the plight of GLBTQ people. He openly opposed political candidates like John Foran and Dianne Feinstein for their absent or phony solidarity, and ridiculed the Board of Supervisors for its failures, hypocrisy, and fawning compliance with downtown interests. “The time has come,” he insisted, “Either the Board and the city agencies give to the gay community what any other group can get or don’t come around courting our votes.”65 He unremittingly indicted police brutality and harassment, which he likened to Nazi oppression of the Jews, exemplified in his published and street protests of the Labor Day beatings at Toad Hall bar and subsequent jailing of the “Castro 14.” In the face of such homophobic discrimination and violence, and bringing together all the elements of his platform, Milk called for economic and political mobilization.66

During the first campaign in 1973, Milk began telling reporters that some were calling him the “unofficial mayor of Castro Street,” a clever moniker. His words and actions during 1974–1975 suggest that he may have perceived himself, and perhaps was beginning to be perceived by friends and enemies alike, as the unofficial, emergent leader of a (new) GLBTQ power movement.67 Milk reflected in a New York Times interview, “I’m a left-winger, a street person. . . . Most gays are politically conservative, you know, banks, insurance, bureaucrats. So their checkbooks are out of the closet, but they’re not. So you try to get something going, and all the gay money is still supporting Republicans except on this gayness thing, so I say, ‘Gay for Gay.’ That’s my issue. That’s it. That’s the big one.”68 It is worth noting that Milk’s candidacy operated within a state and local political culture that connected economic justice, rights discourse, and identity politics. Bell explains, “From the perspective of liberal politicians experimenting with a reconfiguration of the relationship between the individual and society it was inevitable that discussions of social marginalization in the 1950s and beyond would allow a widening of the left-of-center political lexicon that could be responsive to homophile activism. One of Harvey Milk’s early successes as a leading gay activist in the Castro in 1973 was to help the Teamsters extend a boycott of Coors beer into the gay bars, linking gay rights to economic issues.”69

However, Milk suggests in his Sentinel column “Where I Stand,” among the selected documents, that any exclusive political categorization is a foolhardy venture, doomed to being inaccurate or incomplete. Note, for instance, pollster Mervin Field’s analysis in Time, in which he commented on the two tides of the 1975 election: “One is the ebbing tide of traditional liberal, labor and cultural concepts—the idea that government can do it for you. Against this is the rising tide of the ‘new conservatism’—which is related to fear about crime, the inability to get services from government, and fiscal responsibility.”70 The Harvey Milk of his second campaign, perhaps paradoxically, passionately espoused positions consonant with both tides Field identified.71 The ponytail shorn, replaced by a second-hand, two-piece suit, Milk’s hippie persona yielded to a clean-shaven one no less down to earth and outspoken but with broader visual and thus political appeal. Shilts reported that, “Milk’s appearance and demeanor became so devastatingly average that he sometimes had to fend off allegations that he was actually heterosexual. ‘If I were . . . there sure would be a lot of surprised men walking around San Francisco.’”72

Although Milk’s second campaign has received comparatively scant attention, its significance should be understood in relation to the political traction he was gaining, the progressive muckraking he was advocating, and the gay rights agenda his visibility was advancing. The Bay Area Reporter’s preview of Milk’s campaign reveals the extent to which his vision had retained a balance and connectedness between GLBTQ concerns and those of all San Franciscans: “Milk’s four-point program calls for a ‘Fair Share’ tax for those who work in The City but don’t live here, for taxis and buses to be equipped so they can report crimes-in-progress directly to Police headquarters, for the Fire Department to be supplied with the most modern equipment available, and for ‘the Board’s present sense of priorities to be reoriented to the people and not to downtown interests.’”73 Indeed, his “Milk Forum” columns throughout 1975 not only reiterated the GLBTQ power blueprint he had been articulating but addressed a broad range of local issues, including national and city economic conditions, MUNI deficiencies, Yerba Buena development, property tax assessments and housing, bail bondsmen, the Coors boycott (again), and the police strike.

Of course, his gay rights advocacy continued apace during the 1975 campaign. In his “Milk Forum” columns, he railed against City Hall for not providing funds for the Gay Freedom Day Committee while doing so for others, and decried the lack of media coverage of an event with more than 80,000 participants and spectators; he reminded his readers of the value of holding their vote pledges so as to get the most from their political “friends” he urged a continuation of the GLBTQ Coors boycott even after the national Teamsters eliminated the local chapter’s effort; he called for lobbying in support of AB489 and AB633, the consenting sex and fair employment legislation pending in the California Assembly.

Significant, too, about the 1975 election is that candidates, especially for the mayoralty, courted votes and endorsements from the GLBTQ community as never before. Perhaps because of Milk’s trenchant critiques of the “gay groupie syndrome” and his passionate call for GLBTQ political power through decisive voting blocs, campaign hopefuls became increasingly attentive. How remarkable it must have been to read in the Los Angeles Times Supervisor John L. Molinari proclaiming, “The gay vote is a key element for any elected official in San Francisco.”74 Or to see mayoral candidate Dianne Feinstein chanting for the gay men’s softball team against rival police department at their fourth annual game; or to hear that Feinstein had hosted and presided over the lesbian wedding of Human Rights Committee liaison Jo Daly and her partner. Or to finally witness the passage of the state law legalizing sex between consenting adults, thus defeating sodomy’s long criminalization, thanks largely to State Senate Majority Leader and mayoral candidate George Moscone and his ally Willie Brown. Moscone’s conservative opponent in the runoff that December learned the hard way that you ignored or maligned “you people,” a term he used in a well-publicized meeting, at your political peril. Moscone publicly thanked Harvey Milk in his acceptance speech.75

Though Milk was not victorious, he finished seventh behind six incumbents out of a twenty-nine candidate field, despite renewed opposition from gay establishment politicos, with 52,649 votes, strongly supported from the Castro (where he garnered 60–70 percent) to Haight-Ashbury and Pacific Heights.76 Jim Rivaldo, who along with Frank Robinson and Danny Nicoletta had joined Milk that year, proclaimed in light of the prescient color-coded map at Castro Camera, “We got the hippie, McGovern, and fruit voters.”77 Milk described the GLBTQ presence in this campaign season as having achieved “unprecedented political influence.”78 Despite the defeat, Milk had arrived. As Clendinen and Nagourney observe, “No one considered him a fluke anymore. He was part of a phenomenon, the sheer accumulation of gay influence in the city. . . . The boldest, most visible new element of that voting population was in the Castro, and by the end of 1975, Harvey Milk was clearly its voice—and the most public gay figure in the city.”79

Were further proof needed of Milk’s new political capital, it came in Mayor Moscone’s appointment of him to the significant Board of Permit Appeals. (It had not hurt, of course, that Milk had publicly offered his unsolicited support to candidate Moscone in the run-off mayoral election against Supervisor John Barbagelata). Openly gay Commissioner Milk: a first in U.S. politics. As his friends and allies remembered, it certainly had a ring to it. Moscone called Milk “a pioneer.” Even better, he said Milk wouldn’t be a pioneer for long—the Bay Area Reporter headline read: “Moscone: Milk Appointment Is Just the Beginning.”80 The GLBTQ promise of the Moscone Administration was deepened by the appointment of Charles Gain as the first chief of police to publicly avow support for out cops on the force (for which Milk had been clamoring), as well as the election of District Attorney Joe Freitas, who pledged to end prosecutions for victimless crimes.81 In “Milk Forum” he gushed, “[T]he gay community now has a mayor—for the first time ever!—who is not only understanding of our particular problems, but who wants to correct the inequalities.”82

Ever the maverick, however, Milk served the shortest recorded term on the Permit Appeals Board; the Moscone dreams quickly soured. Milk had gotten wind of a purported deal among a number of state and national politicians, including Moscone, California Assembly Speaker Leo McCarthy, Congressmen Phil Burton and his brother John, and Assemblymen John Foran and Willie Brown. It was a multi-move, multilevel political orchestration that would mend rifts and solidify the new Democratic regime in California, with implications for the U.S. Congress. The last person in this political pact: Art Agnos, a McCarthy aide, who would be the heir apparent of the 16th Assembly District—Milk’s District. Board of Supervisors President Quentin Kopp memorably called this political arrangement an “Unholy Alliance.”83 That Mayor Moscone had dismissed Milk from the Board of Permit Appeals on the grounds that one could not hold such a position while campaigning—when he himself had done so a number of times—heightened the stench for some. In the Bay Guardian article entitled “Ganging Up on Harvey Milk,” Bruce Brugmann and Jerry Roberts railed against what they described as “a naked, unabashed power play. . . . The hypocrisies abound.”84

True to political character, Milk was outraged by the machinations. As he said in his declaration of candidacy, among the selected 1976 documents: “I think representatives should be elected by the people—not appointed. I think a representative should earn his or her seat—I don’t think the seat should be awarded on the basis of service to the machine.” Given the math—what that impressive map indicated about voting patterns in Milk’s campaigns, the 1974 vote total in the 16th District for John Foran, and the fact that Art Agnos was a political unknown—Milk’s prospects for success appeared strong. “Milk vs. The Machine” became the slogan derived from media that fanned Milk’s audacious challenge. This crusade seemed very much in keeping the vision Milk had championed since 1973. He wrote on his 1976 “Declaration of Candidacy” application: “My candidacy gives you a choice. Machine politics or an independent voice? . . . A Machine doesn’t serve people, it rewards only people who slave it. I will fight to prevent San Francisco from becoming a Chicago politically.”85

Perhaps it is too obvious to call Milk’s Assembly campaign a transitional moment, given the requisite performance on the larger stage and greater complexities of California state politics. The transition we have in mind here, however, is toward a national political arena, one that made possible his deft leadership in engaging and exploiting the more familiar homophobic national spectacle of 1977. Although Milk had always commented on issues of national concern, in 1976 his commentaries on the impact of the Coors boycott, the Supreme Court’s homophobia,86 Nixon’s legacy, the presidential primary election, California’s Nuclear Initiative, Angola, the failed revolutionary legacy of 1776, Bob Dole, and of course on GLBTQ lives and the gay rights movement all seem to suggest an ever-expanding political vision. After his own race had ended in June, Milk focused much attention on the presidential race. A picture of Milk shaking hands with Jimmy Carter appeared in the Bay Area Reporter, and his endorsement of Carter, announced in the selected document, “’Uncertainty’ of Carter or the ‘Certainty’ of Ford,” was enthusiastic despite Carter’s discomfort and ambivalence regarding the GLBTQ community. (Milk would later challenge President Carter to address the human rights of GLBTQ people and encouraged a writing campaign to lobby the White House.) Milk counseled his readers and supporters to learn lessons from the African American community by exercising their voting power in the election, by voting as a bloc for Carter and other candidates sympathetic to gay rights.87

At the same time, that broader vista only held meaning in relation to the communities in which one lived, the people for whom one strived and struggled politically. Milk’s hero, as he wrote in the column included in this volume, “My Concept of a Legislator,” was Harry Truman, who

never developed contempt for the common man, perhaps because he had personally waited on so many of them in his Kansas City clothing store. Once in public office, he never patronized his constituents, perhaps because he never forgot the time when he had to file bankruptcy. The people who supported Truman were those who had to sweat for their daily bread, many who may not have been as articulate as others with their tongues, but were loving in their hearts, those who instinctively recognized that no person is born to greatness, but many people rise to it.

His political vision and platform clearly had not changed, and he approached the campaign against the Machine as he had the others, by tirelessly attending every meeting possible, shaking hands and conversing, and by building bridges among those who shared stakes in the Sixteenth District. Frank Robinson remembered, “Everything could be going against him, but he would come back to the headquarters jubilant because he has persuaded one old lady to vote for him. . . . It was as if every person he won over represented an important victory. . . . Those moments meant more to him than anything in the world.”88

Throughout the campaign, and even into the first hours of the election returns, there was cause for hope. Hope, the theme and trope that would come to define Milk’s legacy, had emerged during the 1976 campaign in part because Art Agnos told him, after one of their countless tandem events, that his stump speech was too dour. Perhaps this time Milk underestimated his opponent, who was backed by every prominent politician at the state and local level (including, at the eleventh hour, Gov. Jerry Brown, who had sworn neutrality) and endorsed by the very press (such as the Bay Guardian) that had encouraged Milk and castigated the Machine. The gay establishment, of course, actively supported Agnos; that low moment when they imported openly lesbian Massachusetts state representative Elaine Noble to endorse Agnos (to throw her weight against Milk, whom she had never met) must have stung deeply. Some openly accused Milk himself of being involved in a political deal with the Machine, which he bitterly denounced as a smear campaign. Moreover, Milk may have strategically overestimated his support among Castro voters, spending more time emphasizing non-gay rights issues while Art Agnos highlighted his solidarity with the GLBTQ community. The full-page Agnos campaign ad in the Bay Area Reporter a week before the election packed a punch, however inaccurate: “’Who is really upfront for Gay rights no matter who the audience is?’ . . . If Harvey Milk won’t speak out for gay rights at the Labor Council in S.F., what will he do in Sacramento?” It has been suggested that the 35 percent of the votes Agnos received in the high turnout Castro (Milk garnered 62 percent), compared to the lower turn-out minority neighborhoods where Milk fared worse than he had planned and concentrated, arguably made the difference in the election. The toll was also personal, including the disintegration of his relationship with Scott Smith, and the death threats that resonated with his long-standing foreboding about an early demise.89

Against those long odds, Milk only lost by 3,630 votes of 32,000 cast, though the triumphalism of his enemies writing his political obituary must have only deepened the exhaustion of his third campaign—two in two years—and third defeat. Had he squandered his chance for election to the Board of Supervisors in 1977, as he had his appointment to the Board of Permit Appeals, because of his political willfulness? Were those pundits correct who suggested the margin of Milk’s loss meant that the gay establishment could no longer deliver the vote, thus paving the way for a run in 1977? Was the most significant, and dramatic, act of Milk’s operatic political career yet to come?

One can imagine Milk losing faith in Hope. In addition to the precariousness of his political future, Milk now sought change amid shifting, worsening political contexts in California and nationally, with obvious impact at home. Cultural anxieties in California were running high despite new Governor Jerry Brown’s “big thinking”: “Beneath the glamour of California life, the undercurrent of anxiety had rarely run harder and faster than in the mid-1970s. With the economy in recession, jobless rates stood at almost 10 percent, and the state was coming under growing pressure to raise taxes and slash services. Factories and employers were heading south, their tanks and theaters were closing, and people were increasingly moving out of the big cities.”90 Was there glumness in Milk’s interview with the San Francisco State University student paper, Zenger’s? “I’m deeply in debt, my store’s deeply in debt. It’s a struggle to get out. . . . I just took my stand and lost, unlike other politicians who get involved just to fill their egos and their pockets. But I knew the consequences of running, but it’s vital that someone raises the questions. Such as, why is there crime? Not how to stop it by using more police. Why is there unemployment and why has industry been driven out of town?”91

More ominously, evangelical and social conservatives, alarmed by what they perceived as widespread moral deterioration in a climate of tolerance and permissiveness precipitating a crisis in the American family, began in earnest to mobilize a movement that would hit full stride after Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980. Paul Boyer explained, “In this decade, the nation’s evangelical subculture emerged from self-imposed isolation to become a powerful force in mainstream culture and politics. . . . When Newsweek magazine proclaimed 1976 as ‘The Year of the Evangelical,’ the editors underscored a phenomenon that was well under way.”92 As Bruce Schulman put it, “Thunder was gathering on the right.” Worse yet, its lightening, prayers being answered, should smite GLBTQ people. “In the rhetoric of the New Right, feminists were second only to homosexuals in the list of villains threatening the American family,” according to Dominic Sandbrook. “If there was one threat that particularly disturbed preachers, it was homosexuality.”93 Texas televangelist James Robison’s battle cry of 1980 could be found forming in the throats of the devout half a decade earlier: “I’m sick and tired of hearing about all of the radicals, and the perverts, and the liberals, and the leftists, and the communists coming out of the closet. It’s time for God’s people to come out of the closet, out of our churches, and change America.”94 And so they did.

The year 1977 proved to be one of the most important in GLBTQ history to date, the best and worst of times, though its memory has been overshadowed by Stonewall and by the tragic events of 1978. The year began with such promise. The long-sought district elections had finally been won the previous November, changing the landscape of municipal politics and quite likely the political fortunes of Harvey Milk, as that color-coded map had long predicted. In his first “Milk Forum” column for the new year, he touted Carter’s presidency and district elections as “changes of influence . . . changes in priorities” that meant good news for GLBTQ people.95 A gay rights ordinance protecting against homophobic discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations had just passed in Dade County, Florida, a noteworthy civil rights victory in what would become a series of such advancements over the course of the year, in unlikely bastions such as St. Paul, Wichita, Iowa City, Champaign-Urbana, Aspen, and Eugene. A number of states were considering similar legislation. Wyoming became the 19th state to legalize sex between consenting adults of either gender. Shilts described the “year of the gay”: “The year, it seemed, surely would show that the gay movement had reached the juggernaut status; nothing could stop this idea whose time had come.”96

Ironically, the year would be consequential for the movement because an evangelical pop singer and sunny endorser of Florida orange juice named Anita Bryant thwarted the gay rights juggernaut in a Manichean showdown. Bryant’s wholesome persona, Donna Reed looks, mellifluous voice, conservative values, and devout faith—embodiments of what we now know familiarly as family values rhetoric—made her a powerful spokesperson for a homophobic campaign to repeal the Dade County gay rights ordinance that in its own right threatened to become a national juggernaut and a harbinger of the New Right. Calling itself “Save Our Children,” the repeal effort trafficked in the invidious and intoxicating fear appeals regarding homosexual “recruitment.” As Bryant, in a characteristic harangue, charged, “What these people really want, hidden behind obscure legal phrases, is the legal right to propose to our children that there is an acceptable alternate way of life. . . . No one has a human right to corrupt our children. Prostitutes, pimps, and drug pushers, like homosexuals, have civil rights, too, but they do not have the right to influence our children to choose their way of life.” Bigotry never sounded so sweet. It took no time at all to gather the required signatures (plus 50,000 more in addition) to secure a special election in June of 1977 that would become known as “Orange Tuesday.” Gay rights operatives from both coasts took their stand on the battleground of Miami. But their rational arguments proved to be no match for commercials featuring provocative images from the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day parade, and the refrain of children in peril, accompanied occasionally by Bryant’s rousing version of “Battle Hymn of the Republic” (and her labeling of gay people as “human garbage”).97

Harvey Milk brilliantly rose to the challenges of this shameful episode in U.S history (though children are not taught this blight in today’s classrooms). For months prior to the vote in Dade County, Milk used “Milk Forum” as a bully pulpit to mobilize against Anita Bryant, calling for a boycott of Florida orange juice, her firing, and an indictment against her for “inciting violence against Gay people.” He chided those who did not take her seriously, who were apathetic about participating in the boycott, and he excoriated the National Gay Task Force (NGTF), which defended her right to free speech. In response, he exclaimed, “Well, what about the rights of all those people who are fire-bombed because they are Gay? What about the rights of all who are, and will be, discriminated against because they are Gay? What about the rights of all who become victims of Anita Bryant’s preaching? What about the rights of Ovidio Ramos? Where is our great NGTF when it comes to Gay people who are beaten and lose their jobs?”98 Milk linked Bryant’s hate speech to recent public discourse by Supervisor Feinstein and Assistant District Attorney Douglas Munson in San Francisco that homophobically associated the “crime wave” with public sex spaces in their effort to relocate such businesses to a dilapidated section of the city.99

On June 7, the repeal passed with nearly 70 percent of the vote. Milk had not been enlisted by the gay establishment for the fight on the ground in Florida, but unlike more “respectable” representatives he became the de facto leader of the throngs of GLBTQ and allied people in the Bay Area who reacted to the repeal. Arguably, Milk was now a national leader of the gay rights movement. As in cities around the country, thousands took to the streets of San Francisco on Orange Tuesday and every night for the better part of a week thereafter, during which Milk’s presence towered. That first night is best remembered because Milk transformed the massive demonstration that threatened to turn violent (“Out of the Bars and into the Streets!”) into a five-mile peaceable march throughout the city, culminating in a rally of 5,000 at the steps of City Hall; the front-page Chronicle photograph of Milk with his familiar bullhorn captured well the spirit and achievement of the massive demonstration and its leadership. Clendinen and Nagourney observed:

[T]he midnight march was wholly a product of the city’s new gay population, one angry and aroused, with its own neighborhood, its own distinct cultural values, its own community organizations and leaders, and its own way of reacting to events. Anita Bryant’s victory had helped bring them into focus. As a large red banner emblazoned with the words “Gay Revolution” was run up the flagpole on Union Square that night, there was a new reality in San Francisco, and it was emerging in the middle of a crucial political campaign.100

Milk quelled violence even as he wasted no time in escalating his bellicose rhetoric so as to frame Dade’s outrage as a catalyst for intensified activism. “Without the President and the national leaders taking a stand, this will be a struggle like the black civil rights or the anti-Vietnam movements. . . . There will be violence and bitterness and the nation will be seared, but if we have to do battle in the streets we are ready to.”101

As the selected 1977 documents vividly convey, Milk believed Orange Tuesday to be a watershed event, “a victory deeper than the actual vote,” a swiftly rising tide of visibility, consciousness, and mobilization. “This was our Watts, our Selma, Alabama.” In a powerful turn of affect and logic, Milk thanked Anita Bryant, for “she herself pushed the Gay Movement ahead and the subject can never be pushed back into the darkness. . . . [S]he has, in fact, started what so many of us have talked about—a true national Gay Movement.”102 And Milk did shape his public discourse on Orange Tuesday with an eye toward the coming election. In his candidacy announcement later that month, during the Gay Freedom Day celebrations, Milk asked where the city’s elected officials had been during those days of protest, where had been the “appointed gay officials,” such as his replacement on the Board of Permit Appeals and soon-to-be campaign rival, Rick Stokes. “Like every other group,” Milk averred, “we should be judged by our leaders.”

And GLBTQ leadership was needed more than ever. Anita Bryant’s homophobic discourse surely had something central to do with the rise of anti-GLBTQ violence in San Francisco as elsewhere. Although city gardener Robert Hillsborough was murdered by a young man deeply conflicted about his own sexuality, John Cordova’s chanting of “faggot” while repeatedly stabbing his victim marked it as a crime constituted if not directly caused by the same hate speech that Milk found politically galvanizing. Hillsborough’s mother said of Anita Bryant, “My son’s blood is on her hands.”103 This very same fund of hate speech provided gubernatorial hopeful and California state senator John Briggs with an expedient platform, announcing just days after Orange Tuesday his campaign to remove from the public schools “gay teachers” or anyone affirming homosexuality in the classroom. Local politicians took the opportunity to attempt repeal of the recently won district elections and to recall GLBTQ-friendly officials such as Moscone, Hongisto, and Freitas, a nail biter not resolved favorably until the mid-summer special election. Across the nation, concerted efforts began to roll back gay rights, repeal campaigns that by 1978 would prove successful in St. Paul, Wichita, and Eugene.104 Assemblyman Art Agnos decided not to pursue promised gay rights legislation within the current climate created by Bryant and the Dade repeal.105

Within this broad combustible and propulsive political context, Milk stayed true to the vision he had forged through three previous campaigns. He never wavered from his position that GLBTQ people needed an “avowed gay leader” in office, one who was not beholden to those straight liberal “allies” who retreated from their pledged support whenever the political temperature on homosexuality rose precipitously. During this campaign, Milk first called for a statewide “gay caucus” and convention that would mobilize community across political, social, and other lines to create a unified front and influential bloc designed to test the commitment of any aspirant politician—local, state, or national—on gay rights issues. In the 1977 selected documents and elsewhere, Milk again was writing about what he called “gay economic power” and the representational power of a visible “lifestyle.”106 In his speech to the San Francisco Gay Democratic Club, he claimed that his motivation for running (running and running and running) was that “I remember what it was like to be 14 and gay.” Inspiring that kid from Altoona, or Des Moines, or wherever the closet needed to be opened in the now familiar refrain of the evolving Hope speech, was Milk’s sine qua non.107

Yet, even with a heightened emphasis on gay rights, Milk’s campaign vision and platform still embodied the populist, neighborhood activist fighting for all people in District 5 and across San Francisco, voicing issues that mattered to African Americans, Latinos, women, the elderly, and heterosexuals. In “Milk Forum,” he openly called for a coalition with other minorities.108 As he declared in his 1973 Address to the San Francisco Joint International Longshoremen & Warehousemen’s Union and Lafayette Club, “People are more important than buildings and neighborhoods, more important than freeways.” This was still Milk’s mantra, one that made his call to GLBTQ people that “we must learn from history that the time for riding in the back of the bus is over” broadly resonant, even in this virulently homophobic period.