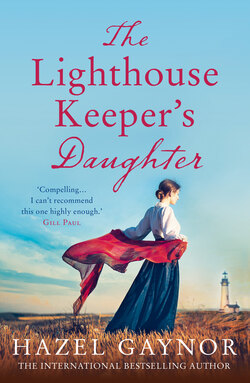

Читать книгу The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter - Hazel Gaynor - Страница 9

CHAPTER ONE SARAH S.S. Forfarshire. 6th September, 1838

ОглавлениеSARAH DAWSON DRAWS her children close into the folds of her skirt as the paddle steamer passes a distant lighthouse. Her thoughts linger in the dark gaps between flashes. James remarks on how pretty it is. Matilda wants to know how it works.

“I’m not sure, Matilda love,” Sarah offers, studying her daughter’s eager little face and wondering how she ever produced something so perfect. “Lots of candles and oil, I expect.” Sarah has never had to think about the mechanics of lighthouses. John was always the one to answer Matilda’s questions about such things. “And glass, I suppose. To reflect the light.”

Matilda isn’t satisfied with the answer, tugging impatiently at her mother’s skirt. “But how does it keep going around, Mummy? Does the keeper turn a handle? How do they get the oil all the way to the top? What if it goes out in the middle of the night?”

Suppressing a weary sigh, Sarah bobs down so that her face is level with her daughter’s. “How about we ask Uncle George when we get to Scotland. He’s sure to know all about lighthouses. You can ask him about Mr. Stephenson’s Rocket, too.”

Matilda’s face brightens at the prospect of talking about the famous steam locomotive.

“And the paintbrushes,” James adds, his reedy little voice filling Sarah’s heart with so much love she could burst. “You promised I could use Uncle George’s easel and brushes.”

Sarah wipes a fine mist of sea spray from James’s freckled cheeks, letting her hands settle there a moment to warm him. “That’s right, pet. There’ll be plenty of time for painting when we get to Scotland.”

She turns her gaze to the horizon, imagining the many miles and ports still ahead, willing the hours to pass quickly as they continue on their journey from Hull to Dundee. As a merchant seaman’s wife, Sarah has never trusted the sea, wary of its moody unpredictability even when John said it was where he felt most alive. The thought of him stirs a deep longing for the reassuring touch of his hand in hers. She pictures him standing at the back door, shrugging on his coat, ready for another trip. “Courage, Sarah,” he says as he bends to kiss her cheek. “I’ll be back at sunrise.” He never said which sunrise. She never asked.

As the lighthouse slips from view, a gust of wind snatches Matilda’s rag doll from her hand, sending it skittering across the deck and Sarah dashing after it over the rain-slicked boards. A month in Scotland, away from home, will be unsettling enough for the children. A month in Scotland without a favorite toy will be unbearable. The rag doll safely retrieved and returned to Matilda’s grateful arms, and all interrogations about lighthouses and painting temporarily stalled, Sarah guides the children back inside, heeding her mother’s concerns about the damp sea air getting into their lungs.

Below deck, Sarah sings nursery rhymes until the children nap, lulled by the drone of the engines and the motion of the ship and the exhausting excitement of a month in Bonny Scotland with their favorite uncle. She tries to relax, habitually spinning the cameo locket at her neck as her thoughts tiptoe hesitantly toward the locks of downy baby hair inside—one as pale as summer barley, the other as dark as coal dust. She thinks about the third lock of hair that should keep the others company; feels the nagging absence of the child she should also hold in her arms with James and Matilda. The image of the silent blue infant she’d delivered that summer consumes her so that sometimes she is sure she will drown in her despair.

Matilda stirs briefly. James, too. But sleep takes them quickly away again. Sarah is glad of their innocence, glad they cannot see the fog-like melancholy that has lingered over her since losing the baby and losing her husband only weeks later. The doctor tells her she suffers from a nervous disposition, but she is certain she suffers only from grief. Since potions and pills haven’t helped, a month in Scotland is her brother’s prescription, and something of a last resort.

As the children doze, Sarah takes a letter from her coat pocket, reading over George’s words, smiling as she pictures his chestnut curls, eyes as dark as ripe ale, a smile as broad as the Firth of Forth. Dear George. Even the prospect of seeing him is a tonic.

Dundee. July 1838

Dear Sarah,

A few lines to let you know how eager I am to see you, and dear little James and Matilda—although I expect they are not as little as I remember and will regret promising to carry them piggy back around the pleasure gardens! I know you are anxious about the journey and being away from home, but a Scottish holiday will do you all the world of good. I am sure of it. Try not to worry. Relax and enjoy a taste of life on the ocean waves (if your stomach will allow). I hear the Forfarshire is a fine vessel. I shall be keen to see her for myself when she docks.

No news, other than to tell you that I bumped into Henry Herbert and his sisters recently at Dunstanburgh. They are all well and asked after you and the children. Henry was as tedious as ever, poor fellow. Thankfully, I found diversion in a Miss Darling who was walking with them—the light keeper’s daughter from Longstone Island on the Farnes. As you can see in the margins, I have developed something of a fondness for drawing lighthouses. Anyway, I will tell you more when you arrive. I must rush to catch the post.

Wishing you a smooth sailing and not too much of the heave ho, me hearties!

Your devoted brother,

George

x

p.s. Eliza is looking forward to seeing you. She and her mother will visit while you are here. They are keen to discuss the wedding.

Sarah admires the miniature lighthouses George has drawn in the margins before she folds the letter back into neat quarters and returns it to her pocket. She hopes Eliza Cavendish doesn’t plan to spend the entire month with them. She isn’t fond of their eager little cousin, nor her overbearing mother, but has resigned herself to tolerating them now that the engagement is confirmed. Eliza will make a perfectly reasonable wife for George and yet Sarah cannot help feeling that he deserves so much more than reasonable. If only he would look up from his canvas once in a while, she is sure he would find his gaze settling on someone far more suitable. But George will be George and even with a month at her disposal, Sarah doubts it will be long enough to change his mind. Still, she can try.

Night falls beyond the porthole as the ship presses on toward Dundee. One more night’s sailing, Sarah tells herself, refusing to converse with the concerns swimming about in her mind. One more night, and they’ll be safely back on dry land. She holds the locket against her chest, reminding herself of the words John had engraved on the back. Even the brave were once afraid.

Courage, Sarah, she tells herself. Courage.