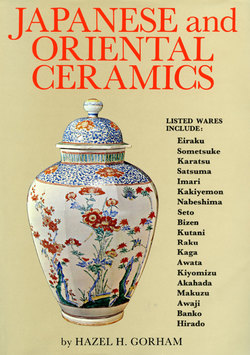

Читать книгу Japanese & Oriental Ceramic - Hazel H. Gorham - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеClays, Kilns

and

Potters' Methods

Location of Ceramic Clays

The cultural, as well as the political and social, history of a country is influenced by its geographical environment and the story of ceramics in Japan illustrates this. An island country lying off the coast of a great continental country Japan was ideally situated to receive cultural impulses from that country. Due to the peculiar geographical construction of her many mountains Japan has an unlimited amount of natural porcelain and pottery clays. Most of Japan's mountains are made up of granite rock and this granite in the natural course of erosion becomes disintegrated and is washed down the mountain-side to form immense deposits of natural kaolin. While the potters of other lands must bring various clays and ingredients for porcelains from different places and mix them, the Japanese potter finds his materials ready to his hand in many places. It is these deposits of natural pottery clays that dictated the location of the earliest kilns. In Japan clay-materials for ceramics presented no problem but the matter of fuel with which to fire the kilns has been a major problem, often necessitating the removal of kilns as the supply of fire wood was exhausted. This fact tends to cause confusion to the European student of Japanese ceramics for as he delves into the history of individual kilns he will find one kiln with its master potter and workmen recorded at more than one kiln site.

Because these kaolin deposits are found at the foot of or on the lower slopes of mountains many Japanese kiln names have some form of the word for "valley" in their composition; as for instance the well-known Kutani which is written with characters meaning "nine valleys." For this reason also Japanese kilns are clustered in groups rather widely separated from one another, and the many kilns of such groups will produce pretty much the same type of ceramic wares, due to the common use of one type of clay materials.

Ceramic making in Japan has always been a group-project. The clay deposits were free to any potter of the district and the kilns were usually under the direct authority of the feudal lord. During the Tokugawa period, the beginning of which exactly coincides with the first crude efforts to make porcelain pottery and porcelain making was an art, not a business. If the kiln, were small it was a family affair with no outside help, if large it was a neighbourhood affair. The firing of the finished wares was done at community kilns. The potters worked primarily not for money, but for love of their craft. The more skilfull potters made wares which their feudal lord gave as presents to his friends and superiors, the less skilfull made the thins that were necessary to the daily life of the potters and their neighbours. This was under the old form of feudalism where the lord was responsible for the livelihood of his men. Later some of the feudal lords kept only one kiln for their own use and encouraged potters at other kilns in their district to make articles for sale. Then after 1868, when Japan became modernized, the kilns became the property of the potters employed in them and the clay deposits went under the joint ownership of the potters. The preparation, that is the excavation and packaging, of ceramic clays is now in the hands of commercial companies and the clays which were once used only by the potters of the neighbourhood are now bought and sold all over the country like any other commercial product.

In the early history of ceramics each group of kilns guarded their trade secrets very strictly. Potters did not openly go from one kiln to another and there are recorded cases where a potter of one location who sold or divulged the secrets of his group to a potter of another group of kilns was punished with death.

Later when such rules and regulations had somewhat relaxed, artist designers went from one district to another, as Ninsei, Oribe and Enshu. Such men made their homes in Kyoto but their influence was felt in many widely separated kilns.

Kyoto is the center of a group of kilns although there are no clay materials to be found there. Kyoto potters use clays brought from great distances. They are attracted to Kyoto because it is the cultural and artistic center of the country. None of the kilns are large, often the master himself is the only worker; and quite unlike the kilns grouped around a kaolin deposit, they are individually owned. Kyoto wares are not difficult to distinguish because they are usually compounded of several clays and carefully and exceedingly well made. Also it was the potters of Kyoto who first signed or sealed their productions.

Kilns

It is thought that pre-historic Japanese pottery was fired in an open fire on the surface of the ground. Historically the oldest kilns are known as cave kilns (ana gama) and may be an adaptation of the primitive charcoal burner's kiln. They were holes dug into the slope "of a hill, or rather open pits dug in the hill-side and covered with a rounded earthen roof. The pit was filled with pottery and covered with earth leaving two openings, that at the lower end was used as a fire box for heating the kiln, the hole at the upper end served as a chimney through which the smoke escaped. Kilns of this type are in use to this day for the production of small quantities of pottery for local use and are now known as oh gama (large kilns). In the days before modern transportation methods were known it was necessary for the Japanese potter to move his kiln from place to place as he exhausted, not his clay supply, but his wood supply, because he found it easier to take his materials to a source of fuel than to bring fuel to his clay deposits; or again groups of potters migrated en masse to a new location in search of fuel.

Showing method of packing and firing pottery kilns. At the top; the nobori gania, below; an oh gama.

The ana gama or cave type kilns were wasteful of fuel and in this connection there is a story which is doubly interesting, first for its bearing on the historical development of ceramic kilns and secondly for the light it sheds upon the importance of the ceramic industry in Japan. During the time of Ogimachi Tenno, who reigned from 1557 to 1586, a certain Kato Kagenobu was a master potter at Kujiri of the Seto group of kilns. He was so jealous of his own secrets of pottery making that he built a fence about his kiln to keep visitors out. Yet when he learned that the type of kiln in use at Seto, the old cave type kiln (ana gama), had been superceeded by an improved form elsewhere, he left Seto and journeyed to Kyushu to learn how to build such kilns. On this visit he evidently learned more than just how to build an improved type of kiln for on his return to Seto he began to make glazed wares. He made articles glazed with a thick soft white glaze which he presented to Emperor Ogimachi. These things so pleased the Emperor that he granted Kagenobu the title of Governor of Chikugo and raised him to Fifth Court Rank. It is well to keep in mind that this was the time of greatest popularity for the cult of cha no yu (ceremonial serving of tea) which so occupied the time and attention of the intelligentia of that day and for the proper performance of which pottery articles were so necessary.

The new type of kiln of which Kagenobu learned was the nobori gama (or climbing kilns). It consisted of series of four or five ana gama set one above the other up the slope of a hill and connected. Fire was built in a fire box attached to the lowest kiln and the smoke and some heat found its way up through the kilns and eventually out at a hole in the upper end of the topmost kiln. To fire a batch of pottery all the chambers were filled with articles of various sizes. Fire was applied to the lowest only and after the things in that chamber had been fired sufficiently that chamber was closed off. Meanwhile, the second chamber had become heated to a certain extent; this was then fired just as if it were an independent kiln and when the articles in it were baked this chamber was closed off and the third chamber was in its turn fired. This continued on to the end of the series. It is said that at times as many as fifty chambers were connected and fired in this manner. Undoubtedly this method constituted a great saving of fuel. These kilns in series are thought to have been influenced by the Korean type of kilns which were built in a series on flat ground. According to some scholars they are simply a development of the primitive ana gama, and it is certain that the two types existed simultaneously during the Momoyama Period (1574-1602). The kilns at first known as cave kilns (ana gama) came to be called old kilns (ko gama) or round kilns (maru gama) when built in series up the slope of a hill, large kilns (oh gama) when built singly.

The Korean kilns-in-series were called split-bamboo type kilns (wari take gama) and were introduced first at Karatsu. Thus we have ko gama, maru gama, and wari take gama all meaning kilns built in series and to these must be added the name nobori gama, when built on a hill, and finally because of a fancied resemblance to baby crabs on a skewer, "baby crab kilns" (kani ko gama).

Since the re-opening of Japan to international intercourse the development of Japanese ceramics has kept pace with developments elsewhere in the world. Beginning with Dr. A. Wagner, a German chemical expert who came here in the early part of the Meiji Period, foreign experts have been invited and the latest and most scientific methods of production are in use. But side by side with coal and oil burning and electrically heated kilns for the mass production of ceramic wares can be found the old Japanese individualistic methods of firing. Although at present only one maru gama, consisting of but six or seven chambers, is in operation (at Seto), many artist-potters still prefer and use the old oh gama (large kiln). They maintain the very irregularity and unevenness of the old method of firing an article produces much more interesting variations and effects than the new mechanically perfect firing. For this stand they have the support of centuries of experience by Oriental potters; and modern science with all its marvels cannot scientifically produce the colours so admired the world over. When the many shades of green, and the reds and the blues, which evolve from one glaze formula conditioned by the heat and smoke of a primitive kiln are considered, the almost superstitious awe with which Oriental potters regard their kilns is understandable. Both Chinese and Japanese potters believe that there is some unseen power operative in the kiln which transmutes their human efforts into something divine, a sort of indwelling kiln spirit. There are even stories in Japan of such marvelous effects being produced that a kiln was deemed uncanny and abandoned. Certain it is that the odd, unusual and individual changes in colour and surface texture produced in the simple.old style kilns cannot be duplicated under mechanically perfect conditions and while the Japanese potter will make for export one thousand things of exquisite beauty all exactly the same, for his own use he prefers every article just a bit different, even if (and perhaps because) that difference is a defect in its perfection.

Japanese methods of making

Japanese potters have known the use of the potter's wheel since pre-historic times, yet all down the ages they have made and even today frequently make articles without its aid. In their big modern factories for making ceramic wares all the known methods of manufacture are in operation; wheel-thrown, jigger-shaped, molded, cast, built-up-in-sections wares pass before operators on endless belt conveyors. The wares are dipped in glaze, sprayed with air sprays or individually hand painted, all at lightning speed in the latest scientific mass production processes. Yet something in the Japanese nature impells them to continue to study and experiment with the most primitive methods of making pottery. They seem to find the fullest aesthetic satisfaction in a hand-made article which reveals the manual skill and mental and spiritual strength of its maker. Neither the disturbances of war nor the harsh demands of materialism have destroyed the ability to make or the love of soft hand-made pottery.

Method of making pottery without using a potter's wheel, even today many Kyoto potters form up porcelain wares this way.

Making pottery wares without the use of the potter's wheel is not unique to Japan of course but the prevalence of such methods is noteworthy. Briefly, there are three methods:

1. Tataki zukuri (making by beating)—This method which seems to have originated in Korea is used in making large articles. A wooden hammer or mallet is used to shape a jar or bowl in conjunction with the bare hand, the mallet on the inside of the article. The pattern formed by the regular strokes of the mallet head is thought to resemble the Japanese conventionalized wave pattern and is called uchi nami, or inside wave pattern.

2. Te zukuri (or hand-made)—The clay material is rolled between the palms into long ropes of a suitable size and coiled round to form the walls of the article. The thing is then more or less smoothed up with the aid of a bamboo spatula and the fingers, but always a trace or suggestion of the rope coils are left. If the article being made, such as a tea cup or a flower vase, needs a footrim (kodai) it is formed of a thin coil of the clay and luted on, or cut and gouged out of the thing itself.

3. Also known as te zukuri (hand-made). With this method a lump of clay is pushed and pulled by the fingers. This makes a heavy looking mug-shaped article and if it is desired to lighten it and shape it the crude mug-shape is reversed and a sharp bamboo spatula is used to sculpture the mass into a finer, lighter shape and form a footrim (kodai). Here the problem is to bring out the shape with the fewest cuts of the spatula and no attempt is made to smooth over or disguise the strokes of the bamboo knife.

The reader will note that with all three methods the inside of the article is left rough and uneven. This is deliberately done. Such articles are usually made for use in cha no yu and the uneven surface is considered an aid in making good tea. Frequently no attempt is made to form a footrim, the bottom of the article is left perfectly flat on all three types. Usually on wares made by any of these three processes a thick soft looking glaze is applied inside and out.

Showing two types of footrim, kodai, and an Eiraku seal. The bowl on the right has the unkin design described on a later page.

Raku Yaki

Raku yaki or raku wares, is a term which gives rise to much confusion in the minds of the Western student of Japanese ceramics for the word "raku" occurs in different settings; as a part of the names of two different historical pleasure pavilions, the Ju raku tei of Hideyoshi in Kyoto at the end of the sixteenth century and of Kai raku en of Tokugawa Harutomi, a Daimyo of Kishu, near Wakayama in the first half of the nineteenth century; and again in the name Kiraku, a potter of the nineteenth century in the Province of Kii as well as in the more famous Eiraku line of potters who worked first at Kutani and later at Kyoto.

Raku has come to mean the general type of pottery preferred by cha jin. The raku in Eiraku is the Japanese pronunciation of the name of an emperor of the Chinese Ming dynasty, Yung Lo; while the raku elsewhere is the character which means pleasure, or amusing accomplishments. The family name of the potters who use the artist name of "Raku" is Tanaka, and in private life they are known as such. Japanese authorities designate as Raku kei a line of potters beginning in the sixteenth century, most of whom have the syllable "nyu" in their professional names. In this sense Raku kei means "House or Line of Soft-Pottery-Made-for-Amusement Makers." Also this line of raku pottery makers has two branches, one known as the Principal Kiln (hon gama) operated by the legitimate successors to the Raku seal and Branch Kilns (wake gama) operated by others than the major line of potters.

This Raku line of successive master potters is an excellent illustration of the custom, followed in all branches of Japanese art, of the master artist naming as his successor to the responsibility of carrying on his style of craftsmanship that one of his pupils he considers best able to do so. If the master's eldest son is a capable artist he of course becomes his father's successor but in case of there being no son to inherit or of the son lacking in ability the master appoints his best pupil to be his successor and use his name. Thus it comes about that the geneology of an artist family is often most irregular; and this is rendered more difficult of understanding by the equally common custom of an artist assuming various names at different times in his life; sometimes, indeed, an artist will use two or more names simultaneously. The knowledge that it was a common practice of a master artist to grant a favourite pupil one character of his name tends a little to reduce this confusion (though sometimes an admirer of an artist borrows a part of that artist's name out of the desire to pay him a compliment!) Other than using a part of their teacher's name, Japanese artists take names referring to or indicating their age, their physical condition (as "the deaf" or "the left-handed), or a part of the name of the district in which they were born or worked.

Two styles of footrim found in Japanese raku yaki and pottery.