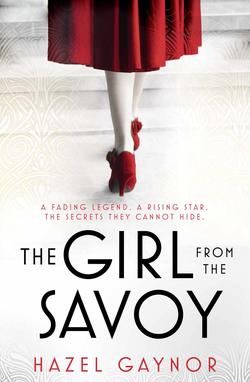

Читать книгу The Girl From The Savoy - Hazel Gaynor, Hazel Gaynor - Страница 11

3 Loretta

Оглавление‘Hope is a dangerous thing, darling. It is usually followed by disappointment and too much gin.’

The soothing lilt of the piano drifts around the Winter Garden at Claridge’s. With a pleasing jazz medley the pianist captivates us all, the music mingling with polite chatter and the jangle of silver teaspoons against fine china cups. The sounds of afternoon tea. The sounds of luxury.

I sit alone at my usual table for two, my brother being habitually late. One would think I would be used to his tardiness by now, but I find it irksome and unnecessary. Seated behind a huge date palm, I at least have a little privacy while I wait. A little, but not too much. The spaces between the foliage afford the guests an occasional glimpse, sending whispered speculations racing across the crisp white tablecloths. ‘Is it her?’ ‘I thought she was in Paris.’ ‘Yes, I’m certain it’s her.’

I smile. Let them whisper and wonder. It is, after all, part of the performance.

I sip my cup of Earl Grey as I watch the raindrops slip down the windowpanes. Mother always insists that tea tastes better when it rains, something to do with precipitation and dampness bringing out the flavour in the leaves. She is full of such tedious nonsense. It is one of the reasons I visit her as infrequently as possible. The fact that she can barely stand to be in the same room as me being another. In any event, despite the inclement weather, my tea tastes peculiar, and there is nothing more unsettling than peculiar-tasting tea, particularly at Claridge’s.

I sniff the milk jug as discreetly as it is possible for one to sniff a milk jug in public. It has definitely turned. Mother would be appalled by the very fact that I take milk in Earl Grey at all. I look around for a waiter but think better of it. I don’t like to make a fuss. Not at Claridge’s. I’m awfully fond of Claridge’s, and besides I can’t summon the enthusiasm to make a proper fuss about anything recently. I decide to forgive this small oversight, assign the bad taste to too many gin cocktails last night, and reserve my annoyance for my wretched brother.

I’m quite aware that Peregrine tolerates our ritual of afternoon tea simply to humour me. He has complained about it since we first started meeting here when he was a jaded young lawyer and I was a bored society debutante. He thinks it unfair that I only invite him to tea and not our older brother, Aubrey, but as I remind him frequently Aubrey is too busy and too married and too full of his own self-importance to contemplate tea with his little sister and brother. We are better off without him.

‘But must we take afternoon tea every Wednesday, Etta?’

‘Yes, Perry. We must.’

‘Might I ask why?’

‘Because afternoon tea is predictable and charming – qualities that should be preserved wherever possible. Because it is one of the few things in my life that I can do without a chaperone, and because if we stop meeting for afternoon tea, who knows what we will stop doing next. Eventually we’ll stop seeing each other altogether. We’ll become distant strangers, like Aubrey, communicating only through a few thoughtless lines scribbled on tasteless Christmas cards. One day we’ll realize that we miss afternoon tea on a Wednesday terribly, but it will be too late, because one – or both of us – will be dead.’

Perry laughed and called me melodramatic, but he kept showing up nevertheless. In the end it wasn’t his lack of enthusiasm that brought an end to our little arrangement, it was war.

Overnight, the carefree privileged life we knew came crashing to a halt as a new and terrifying existence settled upon us all like a suffocating fog. My brothers went to France to serve as officers on the Western Front. I enrolled as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse. Simple pleasures such as afternoon tea became a distant memory until the war ended and my brothers returned. We were all changed irrevocably by the long years between. Now I cling to Perry and afternoon tea at Claridge’s like a life raft, holding on with grim determination, even if his habitual tardiness irritates me immensely and gives me a daylong headache.

‘Would you care for another pot of Earl Grey while you wait, Miss May?’

I glance up at the waiter. A handsome young chap. All taut-skinned and vibrant-eyed. The treasures of youth. ‘I suppose another can’t do any harm.’

‘No, miss. Not on such a dreadful day. And another slice of Battenberg, perhaps?’

I nod. Even the waiters at Claridge’s know my preferences and tastes. It makes life extraordinarily dull at times. ‘And a fresh jug of milk,’ I add.

‘Very well, Miss May.’

He moves with the precision of a principal ballet dancer, pirouetting behind the great ferns and Oriental screens that segment the room into private nooks and crannies. I almost call after him, tell him I’ve changed my mind and to bring Darjeeling and Madeira cake instead, but I don’t. Sometimes it is simpler to keep things as they are.

The pianist plays ragtime as the rain thrums in time against the window. All is a colourless grey smudge outside, weather for reading a racy novel, or for playing backgammon by the fire if one isn’t easily enthralled by the notion of illicit love affairs. Bored and restless, I drape my arm casually over the back of the chair beside me, the creamy white of my skin visible where my sleeve rides up over my wrist. A gentleman at the table to my right can’t take his eyes off me. I stretch out a little farther, languishing like a cat. I am still beautiful on the outside, despite the cracks that are appearing beneath the surface.

The waiter returns and pours the tea as I shuffle in my chair, fussing with the pleats and folds in my skirt, checking my reflection in the silver teapot: perfect golden waves, crimson lips, pencilled eyebrows over hooded eyes, green paste earrings that swing pleasingly as I tilt my head from side to side to catch the best of the light from the chandeliers. Claridge’s has always had flattering light. It is one of the reasons I insist on coming here.

I check my watch. Where the devil can Peregrine have got to?

I fiddle with the menu card, tapping it against the edge of the rose-patterned saucer. Lines of script whirl through my mind like circus acrobats as carefully choreographed steps play out on my feet beneath the linen tablecloth. I cannot sit still. My nerves rattle like the bracelets that knock together on my arm.

It is always the same. Always at three o’clock on the afternoon before opening night when the butterflies start dancing and the jitters set in. Tomorrow is opening night of a new musical comedy at the Shaftesbury, a full-length piece, the female lead written especially for me. The Fleet Street hacks and society-magazine gossip columnists are waiting for me to fail, desperate to type their sniping first-night notices: Miss May’s acting talents are obviously limited to revue and the lighter productions that made her a star. She would be well advised to leave the more challenging roles to accomplished actresses, such as the wonderful Diana Manners and the incomparable Alice Delysia. I feel nauseous at the thought.

The new production, HOLD TIGHT!, is a huge personal and professional risk. I don’t know how I ever let Charles Cochran talk me into it. Presumably it had a lot to do with the wonderful Parisian dresses he promised, and the large volume of champagne we drank on the night the contracts were signed – not to mention the fact that I cannot deny darling Cockie anything. But it isn’t just opening night that has my nerves on edge. There are other matters troubling me, matters far more important than forgotten lines and missed cues. Matters that I do not wish to dwell on.

My only small comfort is in knowing that I’m not the only one feeling anxious today. It is early in the autumn season. New productions open nightly across the city and everyone in the business is skittish. Final dress rehearsals are gruelling fourteen-hour-long marathons. Tempers and nerves are as frayed as the hems on unfinished costumes. The precariously balanced reputations of writers, composers, producers, actors, and actresses are all at stake. Everybody wants their show, their leading lady, to be the big sensation. For established stars such as myself, there is the added threat of the new girls – ambitious beautiful young things who will inevitably emerge from the chorus to become the darling of the season. That dreadful Tallulah Bankhead has already gone some way to shaking things up with Cockie engaging her in the lead role of The Dancers. The gallery girls find everything about her so exotic: her name, her beauty, her quick wit and overt sexuality. Under the glare of such bright young things, is it any wonder I feel dull and worn? It wasn’t so long ago when ambition and beauty were synonymous with the name Loretta May, when I wore my carefree attitude as easily as my Vionnet dresses. I was the darling of the set, wild and free, out-dazzling the diamonds at my neck. But things move quickly in this business. What shines today glares horribly tomorrow. We all lose our lustre in the end.

As the pianist plays ‘Parisian Pierrot’, a popular number from André Charlot’s new revue London Calling!, I spot Perry crossing the road. I urge the pianist to play faster and finish the piece. Perry is fragile enough without hearing the most popular number of the season so far, written by one of his friends. While Perry struggles to write anything at all, Noël Coward could write an address on an envelope and it would be a hit. Thankfully the final chords fade as he is shown to our table, limping towards me like a shot hare, apologizing all the way. He is as sodden as a bath sponge and has a tear in the knee of his trousers. Disapproving stares follow him.

‘Sorry, sorry, sorry.’ He leans forward to kiss me, his stubble scratching my skin. He smells of Scotch and cigarettes. I tell him to sit down. Quickly.

‘You’re an absolute fright, Perry Clements. You look like a stray dog that has been out all night. Where on earth have you been to get into such a state?’

‘In the rain mostly. I bumped into someone near The Savoy. Quite literally. She sent me skittering across the pavement like a newborn foal.’

‘Anyone interesting?’ I ask.

‘No. Just some girl.’ He takes a tin of Gold Flake from his breast pocket, lights a cigarette, and takes a couple of long, satisfying drags. ‘Damned nuisance really. And then the omnibus got a flat, so I decided to walk the rest of the way. Anyway, I’m here now, and while I know you’re desperate to lecture me on appearance and send me straight off to Jermyn Street for some smart new clothes, I’d rather like it if we didn’t squabble. Not today. I have an outrageous headache.’

‘Scotch?’

‘And absinthe. Rotten stuff. Don’t know why anybody drinks it.’

‘Because the Green Fairy is wicked, and everybody else does. I have no sympathy for you, darling. None whatsoever.’

Much as I’d like to, I can’t be cross with him. I don’t have the energy. I take a Turkish cigarette from my case and lean forward for a light, studying Perry through the circles of smoke I blow so expertly. He isn’t unpleasant to look at. A little shoddy around the edges perhaps, but nothing that couldn’t be improved with a little more care. I’m sure he could find a perfectly decent wife if he tried a little harder. There are plenty of young girls in need of a husband, after all. The divine Bea Balfour, for one. But that is a romance I fear I will never see flourish, despite my best efforts to get the two of them to realize they are perfectly matched and to get on with it.

‘So who was this girl anyway?’ I ask.

‘Hmm? Which girl?’ Perry inspects the delicate finger sandwiches and miniature cakes on the stand, lifting each one up as though it were a specimen in the British Museum. He takes a bite from a strawberry tart, curls his lip, and replaces it. I smack the back of his hand.

‘The girl you bumped into. Who was she? Anyone we know?’

‘Why do you ask?’

‘Because you paused after you mentioned her. I know you too well, darling. Whoever it was left a mark on you as clear as that unsightly tear in your trouser knee.’

He smiles. ‘You’ve been reading Agatha Christie novels again, haven’t you? We’ll make a detective of you yet!’ I glare at him. I am in no mood for jokes. ‘Oh, all right. She’s a maid. Not the daughter of an earl, or a beautiful American heiress. I know what you’re thinking and she was most definitely not marriage material. Pretty young thing, though. Eyes to make you wonder. She made me laugh, that’s all.’

‘Goodness! Well, I hope you invited her to dinner. Perhaps she could make you laugh more often and we could all be cheered up.’

He pours milk into his tea. ‘I’m not that bad. Am I?’

‘Yes, you are. Honestly, darling, sometimes it’s like spending time with a dead trout. And you used to be such tremendous fun.’ I stop myself from saying before the war, and take a sip of my tea. The milk is fresher, and the tea tastes better. Perhaps Mother is right about the rain.

Perry relents a little. ‘Well, perhaps I have been more serious of late. But the way the others carry on is ridiculous. Fancy-dress parties and all-night treasure hunts. Did you see the photographs of them dancing in the fountains in Trafalgar Square? Were you there?’

I laugh. ‘Sadly not. It looked like terrific fun, though. The society columnists can’t get enough of them. Bright Young People, they’re calling them. You shouldn’t be so serious, darling. They’re just shaking off the past. Living. You do remember what that feels like?’

‘Running around like bored children, more like. Did you hear they had one of the clues baked into a loaf of bread in the Hovis factory?’

‘I did. And they had to take one of Miss Bankhead’s shoes from her dressing room in a scavenger hunt last month. Of course, she adores the attention. I suppose I’d be part of it if I were ten years younger. When a woman reaches her thirties it seems that she can’t be referred to as a “young” anything, bright, or otherwise.’

‘Well, I think it’s all a lot of foolish nonsense.’

I can feel my irritation with him growing. ‘I wish you were plastered all over the front page of The Times or hanging around in opium dens or literary salons. Anything would be better than hiding away in that dreadful little apartment of yours eternally stewing on things.’ I grab hold of his hand and squeeze all my frustration into it. ‘You can’t change what happened, darling. You can’t bring them back. None of us can.’

We’ve skirted around the same conversation so many times. I cannot understand Perry’s enduring guilt about what happened under his command in France and he cannot understand the apparent ease with which I have put the war behind me. If only he knew the truth.

I take a long drag from my cigarette and change the subject. ‘So, you say this maid amused you?’

A smile tugs at the edge of his lips. ‘A little. She was different. Honest. She told me I looked tired. “Knackered”, actually.’

‘Eugh. Vulgar word, but she’s right. You do.’ I lean back in my chair. ‘Was that it? She insulted you and now you can’t stop talking about her?’

He stares out of the window, watching the rain. ‘It’s you who keeps talking about her! She just seemed different, that’s all. There was something about her. Some infectious indescribable thing that made me want to know her better. For someone in her position she seemed so full of hope.’

‘Hope!’ I laugh. ‘Hope is a dangerous thing, darling. It is usually followed by disappointment and too much gin.’

He casts a wry smile from behind his teacup. ‘Anyway, that was that. She went her way and I went mine. The shortest love story ever told. Now, enough about me. Tell me about tomorrow night. Who’ll be there?’

‘Bea Balfour.’

‘Anyone else?’

‘The usual. But especially Bea.’

He crushes his spent cigarette in the cut-glass ashtray. ‘You’ll never give up, will you?’

‘Not until I see the two of you married. No.’

‘Then I’m afraid you’ll be waiting a very long time. I missed my opportunity with Bea. And anyway,’ he continues, glumly pushing crumbs around his plate, ‘she deserves better. What prospects does a struggling musical composer have to offer a woman like her?’

‘You could always go back to the bar. A successful barrister would be hard to decline.’

‘What, and give Father the opportunity to gloat and prove that he was right all along; that I would never be a good enough composer? I’d rather end my days a lonely old bachelor and see Bea happily married to someone else.’

I sigh and take a sandwich from the tray. I am simply too tired to argue with him.

We spend a tolerable hour together chatting about this and that, but like the withered autumn leaves tugged from their branches outside, my thoughts drift and swirl continually elsewhere. I think about the houselights going down and the curtain going up. I think about the third scene in Act Two. I think about a rapturous standing ovation and the cries from the gallery, ‘You’re marvellous! You’re marvellous!’ I think about the letter in my purse that I have written to Perry but cannot bear to give him.

After kissing him good-bye and imploring him to smarten himself up for tomorrow’s opening night, I take a taxi to the theatre for a final dress rehearsal. A fog has rolled up the Thames and the streets are lit by the orange lamp standards, giving everything a sense of winter. The fog makes my eyes smart and sticks to my face. I feel choked by it and long for the warmth of spring and the flowers that brighten the Embankment Gardens.

As we approach the Shaftesbury Theatre, I see a line of fans already gathered outside the ticket office. The gallery girls: factory girls and shopgirls, clerks and seamstresses, ordinary girls and women who would give anything to live my life. Their adoration and enthusiasm can make or break a star quicker than any society-magazine columnist. I know they adore me and desire my beautiful dresses. If only they knew the truth my costumes conceal.

The front of house sign blazes through the dim light: LORETTA MAY IN HOLD TIGHT! My name in lights, just as I’d imagined when I was a starry-eyed novice in the chorus. Except it isn’t my name. It is the stage name I chose in my desire to leave the real me, Virginia Clements, behind. She was the respectable daughter of an earl, the daughter who had failed to secure a suitable marriage, the daughter who was suffocated by expectation. Loretta May set me free from the starchy limitations imposed on titled young ladies such as myself. She allowed me to be somebody daring and new.

Virginia Clements. Loretta May. Just names, and yet I wonder. Who am I? Who am I really?

That’s the curious thing about discovering one is dying: it makes one question absolutely everything.