Читать книгу On the Doorstep of Europe - Heath Cabot - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Documenting Legal Limbo

Athens “Aliens Police,” July 2009: Armed officers guard the entrance to the compound, a monumental building on a shade-less, fenced, concrete lot. Lawyers and social workers who visit the station regularly are waved through the gates with a smile and a bit of banter, but people with unknown faces must show their papers and explain their business. Those who have appointments at one of the departments, and those accompanied by a lawyer, are usually granted entry. But those who wish to make asylum applications must wait, among the long lines of others waiting, in enormous crowds that cluster in the streets behind the building, invisible to those entering through the main gateway. Presumably owing to the tight surveillance at the external gates, the doors to the building itself are largely free of controls. An x-ray screening system sits to the side of the entrance, dormant and unused, and no one monitors entries and exits—not even the sleeping stray dogs who cool themselves just inside the doorway in the summer heat. Haphazardly arranged photos of Greek tourist attractions, in dusty frames, decorate the walls of the main hall: Meteora, the Olympic complex, a charming island harbor. This high-ceilinged room is a space that people pass through on their ways to various offices and departments, but directly visible to the right as one enters is the crowded waiting area for those awaiting asylum interviews. There, having acquired an appointment to enter the building—after untold hours and even days of waiting in the lines outside—applicants must again wait until asylum officers and interpreters are available to interview them and process their applications.

At the far end of the waiting area is a door marked “interview room,” and directly above the sign is a framed reproduction of an El Greco painting: against a deep blue stormy sky, a ghostly-pale woman looks to the heavens, her eyes rolling up in an expression that is difficult to interpret. I puzzle over this painting with Mariela and Gina, two young social workers who assist women who have been detained. When I suggest that the subject of the painting looks as though she is in pain, Mariela imitates the woman’s rolling eyes and laughs that her expression mimics the boredom of those waiting. We agree that both boredom and pain are appropriate to the atmosphere of the Asylum Division at Allodhapon.

The Aliens and Immigration Directorate of Athens and the Attika Prefecture, on the Boulevard of Petrou Ralli on the outskirts of central Athens, is most often referred to simply as “Allodhapon” [Αλλοδαπών] (of/for aliens) or “Petrou Ralli” by asylum seekers and NGO workers. Allodhapon houses a detention center for undocumented migrants, but during the research for this book it was also the police station with the largest number of officers qualified to examine asylum cases. New applicants filed asylum claims at Allodhapon and police presented them with “pink cards,” the identity documents to which asylum seekers were entitled as long as their claims remained in limbo.1 Allodhapon was thus a central apparatus in the bureaucratic machinery of asylum in Greece; it was also the place where new applicants came face-to-face with the regulatory authority of the state through encounters with the police.

In this chapter I approach the roz karta [ρόζ κάρτα] (pink card) as an entry point into the multiple forms of limbo that characterize asylum seeking in Greece. I follow the pink card’s “career” (Brenneis 2007) or life from its bureaucratic production at Allodhapon, through its circulation in the talk and everyday survival practices of asylum seekers, to its final disappearance at the end of the asylum process. Throughout, I consider how the document also acquired various “lives”—diverse meanings and uses—through the engagements of police, bureaucrats, and asylum seekers. Finally, I consider how the document as a thing-in-itself had an important role in governing both persons and regulatory technologies, and how its materiality enabled and foreclosed various legal, political, and social futures. The many lives of this document highlight the indeterminate relationship between bureaucracy, governance, and subjectivity in the assignment of limbo status.

The Governance of “Things”

Not unlike the U.S. “green card,” the denotation of the pink card through its color was overtly straightforward and yet appropriate. Its pinkness first announced its presence, but you might also have noticed its fragility or makeshift quality. Some cards were wrinkled and torn at the edges; others had been laminated, covered with protective tape, or inserted in plastic sleeves. Cards displayed a photograph of the bearer and the written marks of rushed hands in blue, black, and red inks. Some asylum seekers kept their pink cards casually in their back pockets; others took them gingerly out of wallets or folders, where they had been carefully placed among other documents. Asylum applicants were required to have this document with them at all times, in the event that police stopped them and ask for khartia [χαρτιά] (papers), or taftotita [ταυτότητα] (identification). But unlike passports or credit cards, pink cards were not made to last. The traces of travels, labors, and bureaucracies were rendered tactile on this paper through smudges of dirt and moisture, in creases and folds and crinkled edges. Newly minted cards were sturdier and brighter, while those that had withstood multiple renewals were often wilted like fading roses, washed out through everyday handling by the bearer, police, and lawyers.

In this chapter, I show that through its association with the ambiguities of limbo, this document served to make asylum seekers illegible to both the state and themselves. Recent ethnographic scholarship has shown that “governmentality” (Foucault 2009 [2004]) and subjectivity are mutually and dialogically constituted (Coutin 2000; Coutin and Yngvesson 2006; Fassin and Rechtman 2010; Ong 1999). Despite the fluid interplay between governance and subject formation, however, documents are most often characterized as regulatory technologies that render both citizens and aliens visible or legible to state power (Scott 1998; see also Cohn 1987; Comaroff and Comaroff 1991; Dirks 2001; Mamdani 1996; Torpey 2000). The passport, for instance, brings citizens into the state’s “embrace” (Torpey 2000) with accompanying rights and obligations. Legally present aliens may be marked as such through residence permits or visas, which inscribe a bureaucratic visibility that entails certain benefits as well as exclusions (Malkki 1995a). Those who are undocumented may be “non-existent” within the legal body of the nation-state (Coutin 2000) yet hypervisible (and vulnerable) to the state’s regulatory gaze (Feldman 2011). While documents are, indeed, deeply enmeshed in these politics of legibility and visibility, the effects of such regulatory projects are unpredictable. I show that the pink card, as a technology of regulation, also facilitated highly variable reconfigurations of regulatory activities, as police, bureaucrats, and asylum seekers engaged with and made use of the document.

I also suggest that these many indeterminacies of documenting limbo in Greece expose holes integral to the process of governance itself. Foucault (1991: 93) characterizes the “art of governance” as “the right manner of disposing things so as to lead to an end which is ‘convenient’ to each of the things to be governed.” Describing “things” as “men in their relations, their links” (93), he asserts that governance has multiple teleologies: “a plurality of specific aims … a whole series of specific finalities, then, which become the objective of government as such” (95). Foucault suggests that this plurality of relationships and “things,” which elsewhere he defines as a dispositif (apparatus) (1980 [1977]), has gradually become incorporated into the political formation of the state and its “downward” (1991: 91) mechanisms of regulation. By considering how the pink card figured in a particular project of governance, and the nexus of relationships that in turn “governed” the document, I highlight multidirectional, indeterminate forms of governance that unfold within and alongside the regulatory work of the state.

Origin Stories

The man tells me he was apprehended in Samos, when he came from Turkey in a small boat, and he was detained for three months. A UNHCR committee came a few times—people with lots of different nationalities. A lawyer also visited a few times … and asked if he had any particular requests or demands, and a guy from Algeria translated.

I ask if he applied for asylum there.

He answers that the lawyer had asked if anyone wanted to apply for asylum in Greece. But he did not understand what asylum was. Five men from Africa said they wanted to apply for asylum and they were taken away, but something must have gone wrong, because they were returned, and remained all together. When he was released he was given a deportation letter that was good for 30 days. He came to Athens. A lawyer helped him get “a paper valid for one month,” and he paid 50 euros. Four days after the expiration of his deportation order, he was stopped by the police and detained again for three months. He was then released with another deportation order. When he was released people he knew told him that he must go to “Allodhapon” to get a pink card.

How did he get the pink card, I ask.

He went to a private office near “Allodhapon” which helped him fill in the application. He waited in the queue. A translator asked him his name, and why he came to Greece. He explained that he came to find a job. They took his fingerprints. He got another appointment, and he went to collect his pink card. When the first card expired, he went to renew it, and they took it and gave him this paper (he shows me a rejection of his asylum claim). At that point he came to the ARS, where they helped him file an appeal, and he got his pink card back. (Cabot fieldnotes, March 7, 2008)

On a routine morning at the ARS, I met with a Syrian client, a middle-aged, wiry man with a trim gray mustache, whose direct delivery style sparked the interpreter, Omar, to describe him as a “very matter of fact man,” which is evident in the no-frills summary of our meeting reproduced in my fieldnotes. (This was, of course, a few years before the refugee crisis in Syria incited in 2011.) Despite the significant time he had spent in detention, he recounted his experiences succinctly but in detail, and with a face seemingly clear of emotion. He had entered Greece at an Aegean island border, Samos, but he had received a pink card only many months later, when he came to Athens. His account underscores the circuitous, far-flung, and often shrouded bureaucratic web in which the pink card was entangled.

This loosely articulated web of bureaucracy and policing procedures is, in turn, enmeshed in broader maps of this man’s movements in Greece, encompassing border and transit sites, detention facilities, and police stations. He acquired a pink card not upon his initial entry, but after multiple detentions, and after he had received a number of different documents. In his account, these bureaucratic processes are often obscured or mediated by the corollary presence of other state and nonstate actors: the “guy from Algeria,” the lawyer on Samos, the lawyer in Athens, the “private office” near the police (also very likely a lawyer or notary), the ARS, and the police interpreter. The pink card is similarly mysterious and unpredictable: once he acquired the document, he did not retain it, but it was taken away, and he needed a lawyer’s help to reclaim it.

The asylum application, the structuring event of the asylum process within the host country, implies intentionality and active diligence on the part of applicants. While the events that drive persons to flee, cross borders, and seek protection from persecution are framed in asylum legislation as forms of compulsion, one must, nonetheless, request asylum. The asylum claim thus has a strongly directional, intentional quality, and the pink card, as a documentation of this claim, implied specific pathways of law and bureaucracy, with predictable patterns of connection. Yet when I first started tracking the lives of the pink card through the accounts of asylum seekers, I had incredible difficulty identifying its trajectories. The origins of the document—how someone actually acquired it—were particularly confusing. I met many who spoke of acquiring the pink card only through active and extensive effort, but others seemed to have become asylum seekers almost accidentally, receiving a pink card without asking explicitly for asylum. “Asylum” does not play a significant role in this man’s account, but rather, I myself asked him if he tried to apply for asylum on Samos, thus introducing the category into our conversation. He even went on to clarify that he did not know what asylum meant. When he finally acquired a pink card, it was not because he “applied for asylum,” but because his acquaintances told him he needed a “pink card.”

During the period of my primary fieldwork, asylum seekers could officially make asylum applications at any police authority at the border or within Greek territory, whether they had entered with or without documents. Further, police were formally obligated to accept asylum claims, regardless of the apparent credibility of the case, and issue pink cards upon receipt of the application. As we see in this man’s account, however, the procedure rarely unfolded with such openness, and in fact, efforts to make an asylum application did not necessarily entail acquisition of a pink card. Only police officers trained to hear and examine asylum claims could issue pink cards, the vast majority stationed at Allodhapon in Athens. This meant that border sites were rarely locations where a pink card could be obtained, even though they are prime sites for asylum requests. To lodge an asylum claim on the border, a lawyer most often needed to intervene, as in the man’s account of the five Africans on Samos; and even if one succeeded in making an asylum claim at the border, it was often accepted but not examined, owing again to a lack of competent officers.2 This often necessitated that the applicant go to the central police station in Athens to complete the process. Just as one could acquire a pink card without actively asking for asylum, an active attempt to request asylum often did not result in the acquisition of a pink card.

Analytically, the card cannot be easily located in zones of legality or illegality, but rather, moves unpredictably through the shifting spectrum or “continuum” between illegal and legal status and practice (Calavita 2005; Cohen 1991; Coutin 2000). This Syrian asylum seeker repeatedly traveled in and out of partial il/legality, always positioned precariously in sites of limbo contingent on documents that he might, or might not, possess for long. In particular, his two deportation orders highlight the intimate entwinement of legality and illegality in the culture of documentation surrounding migration and asylum in Greece. Stapled to a memo that included the individual’s photograph, name, and country of origin, the deportation order was often the very first document people received when they entered Greece and were released from detention. Issued to those who had entered Greece in a “clandestine” manner or whose legal permission to stay had expired or been revoked, deportation orders stated that the individual had to leave Greece voluntarily by a specific date, usually within one month.3 Nevertheless, many new arrivals described the deportation paper not as an order to leave but as a permission to stay, or as in this man’s account, a paper “good for one month.”

With the increasing EU scrutiny of and involvement in Greece’s migration management processes since 2010, deportation has become a more regular practice. During my primary fieldwork, however, deportations to home countries were rarely carried out, largely because of the expense involved (though migrants from Albania were often bused or carried in vans to the border, owing to the ease and low costs of transport). Others were expelled to Turkey, even if it was not their country of origin, thanks to the Turkey/Greece readmission agreement discussed in Chapter 1. I met many, however, who were never expelled, even though they had received multiple deportation orders and spent multiple periods in detention. Such protracted periods of limbo can heighten the ambiguities surrounding documentary practices. Farzan, an Afghan interpreter at the ARS, told me that many Afghans asked him how to renew their deportation order. He laughed at this absurdity, explaining that to “renew” it, one simply had to get arrested again, much as this man received a new paper each time he was detained. While the deportation document was formally aimed toward expulsion, it was also interpreted as a temporary permission to stay; arrest thus became a form of renewal.

In the documentary practices surrounding asylum in Greece, illegality and legality are closely entwined, easy directionalities explode, and instead we see reversals, transformations, and objects that—like the deportation order—become chimerical. Attending to the unpredictability, mysteriousness, and even chaos, of the pink card’s bureaucratic movements is crucial, owing to the official and even moral force of the asylum claim, which can grant illusory predictability and solidity to asylum-related bureaucracies. These unpredictable, indeterminate qualities permeated every stage of the pink card’s bureaucratic movements, evident also in how both police and asylum seekers engaged with the document.

Police

Allodhapon, July 2008

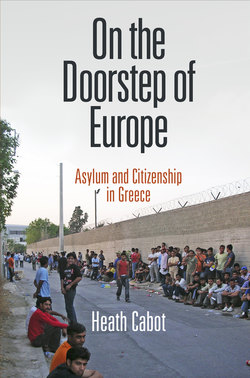

Accompanied by my partner Salvatore, I went to Allodhapon early in the morning to observe the lines of would-be asylum applicants waiting outside the gates behind the compound. We woke at 4:00 a.m., sweat already forming on our skin, and drove down the loud boulevard of Peiraios until we reached the cross street, Petrou Ralli. We parked near Peiraios, about half a kilometer away, then followed a group of men and a couple of solitary women across an adjacent vacant lot that opened onto a narrow street, Salaminas, fortified by high walls topped with wire. As we stepped out into the street I suddenly saw row on row of people on every available spot of sidewalk, some standing, some sitting, some asleep on cardboard boxes, some stretching and yawning. This scene was even stranger in that I had not heard the crowd; they were eerily quiet and subdued. Looking to my left, in the direction of the station itself, I saw a small cluster of women waiting together and identified what had made the crowd so quiet: a police car parked sideways in the middle of the street blocking further passage, and three visibly armed police officers, two men and one woman.

Allodhapon is a place where a certain invisibility is desirable for researchers. In 2008, heavy criticism by activists, journalists, and NGO workers regarding practices at Allodhapon had made police particularly suspicious; those who took pictures of the crowds were harassed, and an English journalist acquaintance of mine, who had been filming a report for the BBC, was interrogated and his tapes confiscated. As the only light-skinned woman in sight (among so few women in general), it was almost impossible for me to blend in, so Salvatore went to observe the front of the line, where his beard, dark hair, and gender might provide some protection. Meanwhile, I walked a few blocks to the back of the line.

I approached a number of people and asked in both English and Greek why they were waiting, in order to gain insight into how they themselves described their activities. One man who told me that he was from Pakistan explained in English: “Here for paper. Political stay. UN.… Red card.” Then, switching to Greek, he clarified that he had khartia (papers), and he took out his pink card to show me, but he had come with a friend who did not have papers. Without papers, he added, you cannot go openly in the street and cannot work regularly. Two other men approached us. Also from Pakistan, they greeted my conversation partner with familiarity. One of them, clutching an asylum application protected in a plastic sleeve, explained that he had been in Greece for six years, and I was surprised to learn that only now was he trying to obtain papers. His companion said that he too was here for papers, because without them he must always stay at home and cannot go out.

Figure 2. At Allodhapon: the line of people waiting to apply for a pink card, July 2008. Photo credit Salvatore Poier.

The bureaucratic pathways for acquiring the pink card positioned new asylum applicants directly outside the central structure of police power for “aliens” in Athens. While asylum seekers often traveled to the capital from border sites to initiate applications, the militarized waiting zone at Allodhapon remade the border within the city in a spatial and temporal enactment of limbo. Applicants had to wait to cross the threshold from illegality into limbo through the acquisition of papers, and, more directly, entry into the building itself. The pink card thus conveyed both protective attributes and the terror associated with the policing apparatus of the state, providing protection from the very authorities that distributed it. None of the men I spoke with mentioned applying for asylum as their primary rationale for being at the police station, though the first man, who spoke specifically about the “red card,” demonstrated a clear acknowledgment that this paper was related to “political problems.” Their aim, however, was papers, because without papers they moved in fear.

As we were speaking, we heard disturbances from the front of the line, and some of the men around us began to move toward the barricade; one of my companions explained that they were starting to “open the doors.” The disturbances increased—men pressing into the crowd, some shouting, surging forward then back. Groups of young men began to run away from the barricade toward the back of the line, many of them laughing, shouting to each other the Greek expletive Fiye re malaka [Φύγε ρε μαλάκα] (“Go away, jerk-off”) and fighe, mavre [φύγε μαύρε] (“Go away, black man”)—a mimesis of a police officer’s shout thus transformed into a source of both humor and challenge.

Meanwhile, Salvatore had made it all the way to the very front of the line and was present when the doors opened. He later gave me the following account, which I summarize here. The police controlled the crowd with gas, and one police officer, in particular, openly hit people with his hands and a stick. Once the crowd was quiet, an older man came out, with white hair and glasses, wearing no uniform but a simple white shirt: apparently a bureaucrat, not an active officer. As Salvatore explained to me later, the police officers attending this man made everyone sit on the street, and he then began “choosing” people by “looking at their papers [their asylum applications] and their faces.” People held up their applications for him to see, and he began picking faces out of the crowd, announcing that they wanted people from Africa, and about 20 Africans came forward. The man admitted about 20 others, mostly from Afghanistan and Iraq. Then the choosing was over, and the doors were shut.

Alongside more spectacular forms of policing at Allodhapon, classification categories had a central role in the asylum process. The pink card itself was devoted to recording various categories of identification, including kinship, gender, and national origin. At Allodhapon, however, informal classification categories, which had yet to become official through bureaucratic authentication, both enabled and restricted access to the document. “Choosing” was carried out through a compound usage of papers (application forms) and faces, but the explicit call for Africans highlights also the role of race and the body in shaping these categories, which were only later codified in documentary form. These technologies of race and classification did not necessarily facilitate legibility, however, but were highly unpredictable. As I was speaking with the group of Pakistani men, a green-eyed, wiry man threw his arm around one of my companions, flashing a broad smile. He told me he was from Syria and stated, almost as a matter of pride: “I have been here for four months, every weekend [waiting].… One time I came here with a friend of mine. [From the] same country, we look the same—but they took him and not me!” While the doors of Allodhapon opened selectively, one never knew who would be let in, or why. Uncertainty, however, did not defuse the power of policing practices or surveillance mechanisms but imbued them with an arbitrariness that engendered confusion, frustration, and anxiety.

Figure 3. Asylum seekers waiting to be allowed to lodge an asylum application, July 2008. Photo credit Salvatore Poier.

This account of the pink card and its bureaucratic apparatuses reflects how, through the police, regulatory, “law-preserving” (Benjamin 1999) violence becomes entwined with the terror, unpredictability, and also indeterminacy of state power. The unpredictable, even nightmarish “magic” of the state (Das 2004; Hoag 2010; Taussig 1997) also vitalizes the instruments of regulatory authority with phantasmal dimensions (Nuijten 2003). While policing practices were formally aimed toward increasing control and legibility over asylum seekers, these activities themselves appeared anything but legible or rational (see Herzfeld 1992); the arbitrary, even mysterious qualities of procedures at Allodhapon increased the anxiety and fear among those waiting, who came back week after week in the hopes (but never the certainty) of acquiring the pink card.

Asylum Division, Allodhapon, July 2011

It is summer 2011, and I have returned to Athens for just ten days of follow up fieldwork, in order to examine the reforms currently being instituted in the asylum procedure. Through a kind of miracle, the person in charge of the asylum division at the Ministry of Public Order and Citizen Protection has granted me permission to spend three days with the police, observing first instance asylum applications. Those I tell about my lucky break describe it as a product of the new culture of openness and transparency surrounding the reform of asylum in Greece.

At around 6 a.m., I get a ride to Allodhapon with Dora and Elektra, two acquaintances who now work for the UNHCR overseeing first instance asylum interviews. Dora flashes her badge, and following a cordial nod by the officer outside, we pass through the gates, around to the back of the main building, and down a ramp to a basement garage for employees. After picking up three surprisingly decent espressos (which cost about 50 cents each) at a café above the garage, we enter the main building through a side door, and I find myself in the “interview room” of the asylum department. I note how the informality and ease of our entrance contrasts with my earlier experiences at Allodhapon.

In addition to my 2008 participation among those waiting in the lines outside, for years I have heard from ARS workers and asylum seekers about the disorganized, corrupt, and chaotic world of the asylum division, and its entrenched disregard for procedural matters. I have been told that interpreters, not asylum officers, conducted the interviews, flagrantly mischaracterizing their content. I have heard repeatedly of the notorious near-zero percent acceptance rate at the first instance of the asylum procedure. But this was before the new asylum law and the transitional measures that have been put in place at Allodhapon.

Dora and Elektra have both prepared me by asserting that the police are not as difficult as they expected, and some of them are in fact “very good.” Though when they first took on their positions it was hard to establish trust, relationships are now generally very friendly. Indeed, an aura of vibrant, bustling sociability greets the beginning of the workday in the asylum division. Police officers, interpreters, and UNHCR representatives mill around, smoking, drinking coffee, chatting, and arranging files for the day’s series of interviews. Since there is not a uniform in sight, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the officers from the UNHCR employees. A few lawyers drop by to check on cases that are up for review today, including Fani, the wife of my longtime interlocutor Dimitris, a former ARS lawyer who now works as an adjudicator on the appeals board; Fani, with many years of experience in real estate law, is now representing asylum seekers. Many of the interpreters are dressed neatly in gray, collared t-shirts reading METAdrasi [METAδραση], a play on the Greek words for translation (metafrasi [μετάφραση]) and action (drasi [δράση]), an NGO that, among its activities, trains interpreters and contracts them out to the asylum division. Among them I recognize a young Afghan, a former ARS client whom I had last seen in 2008, and he greets me warmly. He too comments on how he has been surprised by his positive experience at the police: he used to hate them, but now that he has seen how some of them conduct their work he wants to say “thank you.” I poke my head out into the main hallway at the waiting area immediately outside the interview hall, packed with those awaiting asylum interviews. I have been told that the lines outside the building have diminished, but that there are still people waiting.

Elektra and Dora suggest that I circulate among the different officers, as they do, to see the different interview styles of the various police. Generally, the UNHCR representatives try to keep moving so as not to get too tired (or bored or overwhelmed) and to distribute evenly the “good” and “bad” officers so no one gets stuck with one for too long. Among the more problematic officers, some representatives gossip, is one who uses the pink card as a kind of bargaining chip: when he interviews persons who he believes are not legitimate asylum seekers, he offers to give them additional time on their pink cards if they agree to say they are in Greece for “economic reasons.” He offers even more time if they get their friends to do the same. For the UNHCR overseers, such practices serve as a reminder of the ad hoc and arbitrary police work they are trying to eradicate.

Elektra, however, sits in with one of the younger officers, who she emphasizes is “very good.” I accompany her into an office cubicle, recently constructed to meet demands for privacy (before, all interviews were conducted in the same room). A young man in jeans and a t-shirt greets me warmly, gesturing to a chair; this is the asylum officer. Next to him behind a computer screen sits the “secretary,” a muscled young man in a tight t-shirt—also a police officer—who takes down notes during the interview directly onto the computer. The asylum officer tells me he was recently hired through the transitional procedure, and has worked in the asylum division for just a few months. He has gone through the specialized training but has never worked in asylum related issues before. From the north of Greece, he applied for this job in Athens because it is compulsory that police officers spend time in the capital. But he claims to enjoy his work, in particular the contact with asylum seekers, though he finds it difficult at times. He agonizes over some of the cases, taking files home and working well into the night doing his own internet research. It turns out that there is no internet at Allodhapon, though the UNHCR reps have laptops and mobile internet devices which allow them to do on-the-spot research to assist the police.

During the interviews I observe, I am struck by this young officer’s enthusiastic and crisp professionalism combined with an almost jovial warmth: well-placed jokes, which alleviate the tensions of the interview process and put the applicants at ease. The first interviewee, from Egypt, is currently in detention. At the end of the interview, the officer issues him a pink card, asking him whether he has ever had a pink card and, if so, where he received it. The interviewee answers that he received a pink card at a different location [from Allodhapon], but does not say where. The officer explains that with his new pink card no one will arrest him, but adds that it is good only for a few months, and in the meantime, his case will be under examination. Indeed, with the reform process, the six-month renewal process is no longer a given, since the decisions are now coming much faster. The asylum seeker asks the friendly officer if he can do anything about the pink card (issue it for longer), or if a lawyer can do anything. The officer is firm, however: he must await the decision on his claim.

Interestingly, this young officer is the one who will be issuing the decision, and it is he who decides the amount of time granted on the pink card. Yet unlike his colleague, who apparently (if gossip serves) relies on ad hoc and arbitrary methods, this officer of the new generation invokes a hidden, impersonal bureaucratic apparatus that produces pink cards and decisions. After hours, he feels very personally the weight of the process, as he ponders and researches decisions. In his contact with asylum seekers, however, he distances himself from the process, presenting himself as a mediator between the bureaucracy and the interviewee. In the new spirit of openness, an ethos of bureaucratic accountability holds sway, which itself serves to shroud police plenary power.

Later, another interviewee—a woman from Georgia—references the violence outside Allodhapon.4 She explains that a few months ago, she went to renew her pink card, but that she was not able to make an appointment; the police officers in charge kept saying ela avrio, ela avrio [έλα αύριο, έλα αύριο] (“come tomorrow, come tomorrow”). But she was afraid, particularly when she saw another woman stripped naked by the crowd after coming out of the building. The young officer shakes his head in disbelief and comments: “last year the situation was not controlled easily,” and the interviewee interjects, explaining that now it is “fine.” When I ask the officer later about the violence outside, he comments that he has heard and seen things, and particularly that the situation was very bad before he came. Yet overall, it strikes me that from his position inside, in the interview room, he does not involve himself in the enforcement measures outside.

These two accounts from Allodhapon point to very different formations of state regulatory power surrounding the pink card. Though the violence I witnessed earlier outside the building contrasts with the relatively warm atmosphere currently unfolding inside, it is not entirely erased. Discussions of the document as an instrument of both protection and enforcement give spectral testament to arbitrary forms of regulatory control and police violence, which persist in and through the reform process. The newer process emphasizes openness, oversight, and bureaucratic accountability, particularly through additions and shifts in personnel, including both UNHCR representatives and a number of newly trained police officers. For the young officer, who is in many ways a product of this new environment, documentary practices and decision making emerge as part of a bureaucratic process and procedure, while enforcement measures remain outside the purview of the asylum division, curtailed both spatially and temporally (outside, and in the past). The old-timers remain, however, attesting to the persistence of another culture of documentation and decision making that is more personalized, arbitrary, yet also flexible. The pink card can be used as a bargaining chip, which dilutes the image of bureaucratic distance and accountability that the young officer cultivates, indicating, for some of the UNHCR representatives, ongoing forms of corruption that undermine the reform process. But for asylum seekers, such as the young Egyptian man, such flexibilities may also enable more immediate goals. In the end, whether the asylum seeker is greeted with a depersonalized but accountable bureaucracy or a highly personalized (and seemingly arbitrary) ad hoc approach depends very much on which officer he or she encounters (see Ramji-Nogales et al.).

In her analysis of the limbo of indefinite detention, Judith Butler (2004) draws on Foucault’s assertion that “governmentality” serves to vitalize the state, replacing traditional forms of sovereignty with diffuse formations of power that grant the state a powerful everyday life. When “petty sovereigns” (57) (in this case, police officers and bureaucrats) enact Greek and European territorial sovereignties through documentary practices, asylum seekers encounter a diffuse disciplinary power, which ultimately remains unpredictable even through emerging forms of bureaucratic accountability. Yet the pink card does not simply reinforce the power of the state; it reflects both police and asylum seekers’ attempts to make this document and limbo meaningful. The very practices that vitalize state power also imbue the pink card with meanings and functions that reshape or even undermine state regulatory activities.

Narrating Limbo

In addition to the powerful physical-spatial dimensions of limbo enacted through policing practices at both Greek and EU scales of governance, limbo is implied in the juridical formulation of asylum seeking itself. Asylum applicants occupy positions precariously between undocumented, paperless illegality and “refugee” status. While recognition as a refugee conveys the right to protection in a host country, the category “asylum seeker” connotes a temporary relationship to a nation-state in which the right to stay is itself highly transitory (Coutin 2005). In seeking asylum, one has asked to be granted the status of refugee, but one has not been “recognized” as such. Asylum seekers thus occupy a neither fully legal nor illegal position of non-belonging, suspended in limbo between multiple bureaucratic stages conveying possible acceptance, rejection, or appeal. If an asylum claim is approved, one is “recognized” as a refugee, but if the claim is rejected, temporary permission to stay is revoked and one is rendered, de facto, an “undocumented” migrant; in Greece, one must leave voluntarily, attempt to employ other methods of regularization, or risk arrest or deportation.

Amid the many ambiguities and instabilities of limbo, the pink card acquired vitality in the intimacies and informalities of daily life, as persons invoked the document through narrative attempts to make sense of their encounters with the asylum procedure. At times, these moments of discursive engagement highlighted the document’s power to immobilize, imprison, or make one vulnerable. Yet individuals also infused the pink card with hopes for belonging, recognition, freedom, access to rights, and economic survival, thus reinterpreting both the pink card and the condition of limbo that it consigned.

In March 2003, with the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the Greek Ministry of Public Order effectively “froze” asylum applications from Iraqis, implicitly anticipating that the situation in Iraq might improve. Between 2003 and 2008, few Iraqi claims were approved or rejected, meaning that many Iraqi asylum seekers could renew their pink cards repeatedly but that their cases rarely progressed to a decision or even a second-instance interview. The extreme difficulty of obtaining an asylum decision made this limbo, for many Iraqis, particularly protracted, lasting months and even years.5 Take, for example, the case of Kamir, an Iraqi Kurd. In an informal interview over coffee in January 2007, he explained that he had been in Greece since before the U.S. invasion of Iraq but that his asylum claim had been “frozen.” He had initially “started out with a pink card,” but after a few years of waiting while working and making a life in Greece, he quit the asylum process and initiated a new process of legalization as an economic migrant, successfully applying for the Greek equivalent of a “green card.” Thanks to his excellent Greek, good education, and an employer who had hired him, this different legalization pathway was ultimately more convenient, and much faster, than the asylum process.6 However, he explained that he was disappointed because he was a refugee and should have been recognized as such.

Kamir’s commentary evoked an ambivalent relationship between the limbo to which he was consigned through the pink card and his own self-identification as a refugee. He suggested that refugee status would have signified the recognition of crucial elements of his experience, while the failure of his asylum claim implied a delegitimization of that history. He discursively associated the green card with this failure, as a document related to economic migration, which labeled him a migrant, not a refugee. A few months after our conversation, however, Kamir traveled back to Iraq to see his family, a trip that would not have been possible had he been an asylum seeker or even a recognized refugee, since the travel document issued to refugees expressly prohibits travel to the holder’s country of origin. Thus, while the green card came to signify a lack of recognition, this document also provided a way out of limbo, with significant forms of mobility.

In addition to the overwhelming frustrations and delegitimizing effects of limbo, many asylum seekers characterized the card as a powerful indicator of physical immobility. Through a series of interviews in spring 2008, Asad, a young man from Somalia, told me how he had attempted a number of entries and undergone multiple expulsions in crossing the border into Greece. After being expelled twice from Greece, in Turkey he arranged for a false passport, and traveled directly from Istanbul to Britain, where his aunt lived. He applied for asylum there, and for a year lived in Manchester while he awaited a decision. The British authorities, however, discovered Asad’s fingerprints registered in Eurodac (the EU biometric data system), revealing that he had first entered the EU via Greece, so they deported him to Athens under the auspices of Dublin II. When he asked for asylum upon arrival at the Athens airport, he was issued a pink card, and finally officially became an asylum seeker in Greece.