Читать книгу A Deadly Distance - Heather Down - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 3

Оглавление“Where have you been?” Mishbee’s mother scolded, obviously not impressed by her daughter’s disappearance. Mishbee was no stranger to the woods, but her absence had been longer than usual.

“I had to finish picking the blueberries.”

“The sun will soon set, Mishbee, and there’s much work to do here. This isn’t the time to wander off. You’re needed. Please don’t disappoint me with your actions again.”

Mishbee hung her head in shame. “I’m sorry, Mother.” She was more repentant than her mother knew. The events of the day had caused her greater grief than she cared to think about.

Still, her mother was right. After a hunt, there was always a lot to do. First, Mishbee placed her berries on a flat rock where the other berries were already laid to dry for tomorrow’s sun. The air surrounding the rock was filled with a sweet berry aroma. Besides blueberries, the women and children picked partridgeberries, marsh berries, raspberries, and currants at various times in the summer. Their only way of preserving this precious fruit was to dry it in the sunlight or store it in oil. While Mishbee worked diligently, Dematith walked by.

“How are you, Little Bird?” he asked, smiling. “I see you found your pendant.” He seemed pleased at the sight of the shiny carving once again hanging around Mishbee’s neck.

“Yes” was all Mishbee said, keeping her head down to avoid his eyes.

“Why are you so sullen, Little Bird?” Dematith asked, his tone changing from cheeriness to genuine concern.

As much as Mishbee usually enjoyed talking playfully with Dematith, she wanted this conversation to end. She had a secret and didn’t want to reveal it. “I’m not sad, Dematith. I’m just grateful to be wearing your pendant again. I didn’t mean to disappoint you earlier.”

Dematith sat and wrapped an arm around Mishbee’s shoulders. “Don’t sound so dejected, Little Bird!”

Mishbee was happy to have Dematith for a friend, since she had never had a brother, only her one sister, Oobata.

“I was only teasing you earlier,” he told her. “I know you appreciate my work.”

There was never any question in Mishbee’s mind that Dematith’s carving was treasured. It had almost cost her life, but she couldn’t tell him that. “Yes, of course Dematith,” she said in her most convincing voice.

Dematith seemed satisfied with Mishbee’s response and walked away to help some of the others.

Mishbee went to attend to the fire with Oobata. With such a good hunt of great auks, it would be necessary to keep the birchbark pots filled with birds. Birchbark, or paushee, as her people called it was so important. The versatile material was used to make the skins of containers, summer wigwams, and canoes.

“Where were you today?” Oobata asked, not wasting any time with her questions. She was always a keen observer and very direct.

It seemed that Mishbee couldn’t escape questions today. “Picking berries,” she told her sister.

Oobata glanced around carefully. A couple of women were working at the next fire. She leaned closer to Mishbee and whispered, “Mishbee, Mother isn’t around. I know you better than anyone else and can see you’re not telling me everything. What secret are you keeping?”

“What makes you think I’ve got a secret?”

“I just know it. You can’t fool me.”

Not only was Oobata her older sister, she was Mishbee’s closest friend. She had been there from the day Mishbee was born and was like a second mother to her. Oobata could sense Mishbee’s joy and dismay before anyone else. Mishbee peered into the dark, solemn eyes of her older sister. Oobata had Mishbee’s complexion but was taller than Mishbee and very wise.

“Mishbee,” Oobata said, “you’re skilled in the woods. It would never take that long for you to fill that tiny basket with berries. And why didn’t you have your pendant when you first came back? I overheard Dematith ask you about it. And I heard you answer him. You said it was in our wigwam. That was a lie, Mishbee. When I went inside, I didn’t see the pendant anywhere. I notice these things, and it doesn’t make any sense to me. The only thing I can be sure of is that you’re keeping a secret.”

Mishbee didn’t want to tell Oobata everything, but she had to tell her something. If she wasn’t truthful, Oobata would know. “I was thinking about the winter feasts, Oobata. I was distracted and didn’t work as hard as I should have in the woods today ...”

Just then Mishbee was interrupted. Her father flew into camp, breathless and agitated. He was a respected hunter and an elder in their small coastal hunting group. Although Mishbee was thankful that she didn’t have to finish her story, it was obvious that something was terribly wrong. The women, the few children, and all the men instinctively gathered around Mishbee’s father. The group felt terror settle over them, and everything seemed to go suddenly still. When Mishbee’s father caught his breath enough to speak, he told them what he had seen. “When I was in the woods, I spotted settlers hunting in the bush just east of our encampment.”

Mishbee gulped. Her father had seen John! This man who had loved and protected her all her life had seen her secret. But that couldn’t be. Obviously, her father hadn’t seen her speaking to John or he would have said something to her by now.

Mishbee’s father continued his story. “At least two of them had muskets. Our land is being taken once again. The aichmudyim has returned! We’re no longer safe here. The council must meet. We must hurry.” Mishbee’s father spoke of the white men as the devil.

In the summer the tribe broke up into small hunting groups of a dozen and a half or so people. But even so a small council was formed to be consulted with before the group made a decision. This was an emergency and there was no time to waste.

With memories of the death of Mishbee’s cousin still fresh in their minds, the council people didn’t take long to decide to move the camp the next morning. The thunderous noise of the musket, the death, the ceremony, the ochre, the birchbark, all of it was etched into their memories as if it happened yesterday. They didn’t want anything to do with the settlers.

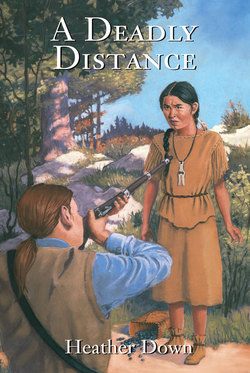

Mishbee crawled into her sleeping nook beside Oobata. The smoke-filled wigwam provided light protection from the summer weather. She curled up in her spruce boughs, but it was useless. That night sleep wasn’t restful for Mishbee. Visions of the settler boy haunted her weary mind. Every time she reached the brink of sleep, she jerked awake as if she were once again staring into the barrel of his musket. She could never tell her father what had happened today. He would never forgive her carelessness. He had loved his nephew as if he were his own son. The grief was too fresh in his mind.

Early the next morning the group gathered up the few tools, skins, and food in order to abandon their campsite. Mishbee hated to leave, but she was used to this nomadic way of life. Every season they followed their food supply.

“You had an uneasy sleep,” Oobata said. “It was as if something were frightening you awake every hour.”

“I’m worried about the settlers,” Mishbee answered truthfully.

Every summer they came to the coast to hunt birds and fish and gather eggs. But the coast was quickly becoming dotted with the settlers’ communities, making it more difficult for Mishbee’s people to access their coastal lifeline.

After everything was packed, Mishbee’s people huddled together with all their earthly possessions to plan their trip. “I saw them inland a little to the east,” Mishbee’s father said. “We should head west.”

The elders of the tiny council agreed, and the group decided to move westward along the coast. It was still too early to go inland where they lived during the winter, and hopefully there wasn’t a new settlement of the foreigners to the west.

The wigwams were left behind, but they would build new ones. The group headed down to the water and into their large canoes. Mishbee remembered watching her father and mother make their canoe. The Beothuks’ canoes were quite different from the settlers’ boats. They were long and had high, curved fronts and backs to protect their occupants from the ocean spray. The canoes didn’t have flat bottoms. Instead the two sides came straight up from the centre, giving the vessels a lot of depth for the unpredictable ocean waters. Rocks were placed in the centre to provide balance and moss was used to provide comfortable upholstery.

To make a canoe, Mishbee’s father stripped sheets of birchbark from the trees, and her mother sewed the pieces together to form a single sheet. Later the birchbark sheet was put on the ground and a piece of spruce was placed in the centre to form a frame. The bark had to be folded to make the sides of the canoe. Then her father strengthened the vessel with tapered poles of spruce, which her mother latched to the bark with split spruce roots. Finally, her father put crossbars in the middle to hold the canoe sides open. Mishbee recalled helping to waterproof the boat with a thick coating of heated tree gum, charcoal, and red ochre.

Now this canoe would save their lives. A half-dozen people climbed into her family’s canoe. The women and children huddled in the middle where the sides extended much wider and higher than the rest of the vessel.

“I haven’t forgotten what we talked about yesterday,” Oobata said quietly into Mishbee’s ear.

Mishbee wished that Oobata would forget.

The canoes and paddlers were efficient. Mishbee loved and feared the ocean all at the same time. It gave them food and travel, but it could also be angry and unpredictable. A great monster lived in the sea, and it was important to respect and not disturb that creature.

Travel was easy today, and they found a suitable site about an hour later in a quiet inlet. After unloading, they quickly busied themselves by building the cone-shaped summer wigwams.

A few of the younger women started digging out a round pit, slightly lower than ground level. The centre of this structure would become the fireplace. The men quickly cut down and gathered birch trees for the frame of the wigwam. Mishbee loved to latch these birch poles together. Many found it difficult, but it was one of her special talents. She was pleased as she worked skilfully and quickly. Oobata helped her, but she wasn’t as good as Mishbee. As the two sisters worked, Mishbee’s father cut birch trees and her mother attended the fire.

Oobata seized this quiet moment for conversation. “Mishbee, you can’t keep secrets from me. The spirits won’t allow it. I’m your only sister! You have to tell me what happened yesterday.”

“Won’t you give up, Oobata?”

“No, I won’t. Not until you tell me your secret.”

Mishbee continued to latch the poles together. Their conversation stopped abruptly when Dematith returned with yet another pole. Impatiently, they waited for him to leave.

Mishbee glanced around to see if anyone was close. “Oobata, the spirits want me to be quiet,” she hissed.

“I was right. Something did happen. Tell me, tell me!”

“No, Oobata, I can’t. As I said before, the spirits want me to be quiet.”

Oobata reflected for a long moment, then sighed. “If the spirits want you to be quiet, you must do as they say.”

“Thank you, Oobata,” Mishbee said, relieved.

“Let’s go get more birchbark.”

The two set out to gather layers of birchbark to tile over the wigwam. This natural shingling would protect them from the weather. Mishbee looked around as they walked about their new camp collecting bark. The rocky coastline was very rugged, and the icy ocean melted into an ominous grey sky.

When they returned, they carefully layered the bark over the frame with their mother. Oobata added some skins and furs to the exterior, leaving only a small hole at the top over the fire hole. When they were finished, the girls went inside their newly created structure to inspect it.

“It looks good,” Oobata said.

“Yes, it is good,” Mishbee said. “I like our new home.”

“We’re good building partners.”

Mishbee smiled at her sister. “And good friends.”

It was hard to believe that this small group of people could construct this temporary home in little more than an hour.

Mishbee went back outside to gather firewood and some tree boughs. She dug out a fire pit in the centre of the wigwam, then scooped out a little hollow for herself to sleep in. Mishbee lined the hole with several boughs and a caribou skin. She was looking forward to curling up in her new bed tonight.

They finished setting up the new camp just in time. The sky grew quite dark, and before long rain fell in great sheets. Lightning illuminated the sky and the thunder spoke. The small band of people eagerly took refuge inside their wigwams.

“When the sky is blue, it’s bluer than the sea,” Oobata said to Mishbee, “but when it’s grey, it’s truly dismal.”

Mishbee heard the pelting rain hit the birchbark exterior. She was grateful that her father had already started a fire in the centre of the wigwam.

“Yes, it’s certainly a dismal night outside,” Mishbee said. But it wasn’t dismal inside the wigwam. She stared at the flickering fire as the flames danced and cast warm shadows on the faces of her family. She didn’t care that it was pouring outside. The past two days had been long and tiring for her. The hours had been filled with hard work, terror, and travel. It was a great relief just to sit around the fire in the comfort of her family’s shelter.

Mishbee’s mother had taken a cormorant that her father had caught and skewered it to roast it on the fire. Mishbee took some of the berries she had picked the day before and ate them with the pieces of flesh off the bird. It felt good to eat, good to be here, and good to be alive.

“Mishbee,” her father said as soon as they finished their supper, “you worked well today. I’m proud of you.”

“Thank you, Father,” she said, pleased with herself.

“You’re a good girl.”

That night Mishbee curled up into a very contented ball. Unlike the previous evening, she closed her eyes and slept well.