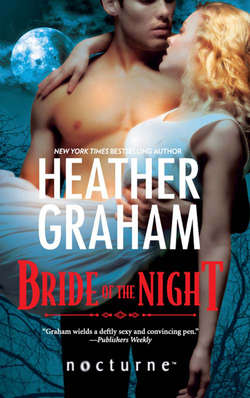

Читать книгу Bride of the Night - Heather Graham, Heather Graham - Страница 5

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеWinter, 1865

“LINCOLN, LINCOLN, LINCOLN,” Richard Anderson said, shaking his head sadly. “Frankly, I don’t understand your obsession with the man.”

Richard pointed out beyond the sand dunes and the scattered pines to the sea—and over the causeway to Fort Zachary Taylor where the North was in control, and had been in control since the beginning of the war, despite Florida being the third state to secede from the Union. He sat down in the pine-laden sand next to Tara, confusion lacing his gray eyes.

“You’re at the southernmost tip of the southernmost state. A Confederate state. I don’t see you gnawing your lip and chewing down your nails to the nub over Jefferson Davis, who has certainly had his share of trouble, too. Seriously,” he said, scooting closer to her, “Tara Fox, if you’re not careful, you’re going to get yourself killed.”

“Getting myself killed is highly unlikely,” she murmured. She smiled at Richard, her friend since childhood. They were seated on the small dunes on the edge of the island, away from the homes on the main streets of the town, and far to the east of the fort and any of its troops that might be about. Tara loved to come here. The pines made a soft seat of the sand, and the breeze always seemed to come in gently from the ocean, unless a storm was nearing, and even then she loved it equally. There was something about the sea when the sky turned gray and the wind began to pick up with a soft evil moan that promised of the tempest to come.

“Hardly likely? More than possible!” Richard said hoarsely. “My dearest friend, your passions make you a whirlwind!”

“Honestly, please. This is a war between human beings. The Northern soldiers don’t run around killing women—from what I understand, they’re only locking up spies when they’re women, and not doing a great job keeping any of them in prison at that.”

“There’s nothing human about war at all.”

“But, Richard, I’m not a spy, and I’m not trying to do anything evil. I just keep dreaming about Abraham Lincoln.”

“My dear girl, he’s not the usual man to fulfill a lass’s dreams of fantasy and romance,” Richard said, grinning widely.

She cast him a glare in which her effort to control her patience was entirely obvious. “Richard, that’s not what I mean at all and you know it.”

“It was worth a try,” he said wearily. “You are like a dog with a bone when you start on something, and it terrifies me.”

Tara ignored that. “I’ve already gone north once, Richard.” She said the words flatly, as if they proved that she could well manage herself. Yet, even as she spoke with such assurance to him, she was startled to feel a chill of fear.

Yes, she had gone north, and, yes, she had been accosted. By an idiot citizen who seemed to think that she was about to offer harm to President Lincoln. Idiot, yes, but …

Canny and observant, he had watched her—stalked her practically!—and stopped her from getting near Lincoln. If she hadn’t been wary …

No, she could take care of herself. If forced into a fighting position, she could take care of herself. And, while highly unlikely, she could be killed, especially if someone really knew or understood just who she was.

What she was.

That was then, long ago now. The man could be dead now, such was the war.

Somehow, she doubted it. She could too easily remember him. Though far shorter than the president, he was well over six feet tall, built of brick, so it appeared, with sharp dark eyes that seemed to rip right through flesh and blood. She remembered his touch all too well. He was a dangerous enemy.

“I’ve been north before,” she repeated to Richard. “I’m not a soldier and I’m not a spy. I’m a traveler. I’m just trying to find a place to live, to find work … I’ve been there, I’ve done it before.”

“Yes, I know, and I didn’t think that it was a good idea then, and I think it’s a worse idea now.”

She touched his hand gently. She couldn’t be afraid, and she couldn’t let others be afraid for her. If she could only make her friends understand that it was almost as if she was being called to help. “Richard, it’s as if he knows me, as if he’s communicating with me through his mind. I don’t know how to explain, but I dream that we’re walking through the White House—and he’s talking to me.”

Richard stood, paced the soft ground and paused again to look at her. “If you want to go, you know that I’ll help you. I just want you to realize what a grave mistake you’re making—absolutely no pun intended.” He hesitated. “This is home. This is Key West. This is where your mother came, and where you are accepted, and where you have friends. It’s where I’m based.”

Tara lifted her chin. “It’s where you’re based. Half of the time, you’re off—trying to slip through the blockade. Speak of dangerous.”

“It’s what I’m supposed to do,” he said quietly.

“You never wanted the war,” she reminded him. “You said from the beginning that there had to be a way to compromise, that we just needed to realize that slavery was archaic and the great plantation owners could begin a system of payments and schooling and—”

“I was an idiot,” he said flatly. “In one thing, the world will never change. Men will be blind when a system—even an evil one—creates their way of life, their riches and their survival. John Brown might have been a murdering fanatic, but in this, he could have been right.” He gazed off into the distance, a bemused look on his face. “The state of Vermont abolished slavery long before your Mr. Lincoln thought of his emancipation proclamation. But do you think that rich farmers anywhere were thinking that they’d have to pick their own cotton if such a law existed? Yes, it can happen, it will happen, but …”

“You’re saying the war is over, that we’ve lost—but you keep going out, running the blockade.”

He lifted his hands. “It’s what I have to do…. But! You don’t have to. You are in a dangerous situation when you leave this place.”

“Richard! I don’t walk around with a sign on my back with large printed letters that spell out b-a-s-t-a-r-d!” she said indignantly.

“Nor do you have a sign that says Be Wary! Half Vampire!” Richard warned.

Tara was silence a minute. “And you’re my friend,” she murmured dryly.

He knelt back down by her in the bracken by the pines near the tiny spit of beach that stretched out along the causeway to the fort. “I am your friend. That’s why I’m telling you this. You know I’ll take you aboard the Peace when you wish … you know that. What I’m trying to tell you is that every journey we make grows more dangerous. The South started the war with no navy, had to scrounge around and build like crazy—beg, borrow and steal other ships—and then count on blockade runners to carry supplies. My ship is good, but the noose is tightening on us, Tara.”

He was quiet for a minute, looking downward, and then he looked up at her again. “Tara, I’m saying this to you now, here alone. If I were heard, it might well be construed as that I was speaking as a traitor, and God help me, I’d fight for my state, no matter what. Yet, every word we’ve spoken here is the truth of it. The war is ending. And we are on our knees, dying. The Confederacy can’t hold out much longer, and who knows, maybe God Himself is speaking. General Sherman ripped Atlanta apart, and thankfully Savannah surrendered before being burned to the ground, as well. Since Gettysburg, our victories have been small and sadly sparse.”

Tara drew her knees to her chest and hugged them. “Yes,” she said softly. “I can read very well,” she assured him.

“The death toll is ungodly.” He might well have been sadly informing himself.

“I know …” She waved a hand in the air. “I know the tragedy of the whole situation, and all the logic. Grant is grabbing immigrants right off the ships and throwing them into the Union forces. The North has the manufacturing—and what they didn’t have, they seized. They’re in control of the railroads, and when the South rips them up, they have the money and supplies to repair them, and we don’t. Lee’s army is threadbare, shoeless, down on ammunition and, half the time, scrounging desperately for food. I know all that, Richard. Like you, I’d hoped that there wouldn’t be a war, and that most people with any sense would realize that it wouldn’t simply be a massive cost in life for all of us.”

She looked at Richard, pain and passion in her eyes. “I think about you, and my friends fighting for the South. And I think about Hank Manner, the kind young Yankee at the fort who helped old Mrs. Bartley when her carriage fell over. Richard, the concept of any of you shot and torn and bleeding is horrible. North and South, we’re all human beings.” She winced. “Well, you know what I mean. Hank is a good man, a really good man.”

She was quiet for a moment, and then added softly, “I think I’m just grateful. It really is all over. I just don’t know why we keep fighting.”

“Human beings. Yes, as you said—it’s the human beast,” Richard said, shaking his head as he looked out to the sea. “Men can’t accept defeat. It hits us at some primal level, and we just about have to destroy everything, including ourselves …”

“So, it may go on. Please, Richard …?”

“The war will go on,” he said harshly. “And it will be chaos while it’s still being settled, and, God knows, far worse after!”

“You can’t understand this urgency I feel,” she told him.

He gripped her hands. “Tara, it makes no sense! Why in hell are you worried about Abraham Lincoln? He’s been elected, again. He’ll be inaugurated soon, again. He’ll be the conquering hero of the United States. What, are you crazy? There are professional military guards who worry about his safety, friends who watch over him. And Pinkerton guards …”

“He surely can’t imagine the amount of enemies he must have.”

“But, Tara—” Richard began, and then he just shook his head and went silent with frustration.

She smiled, touching his face tenderly. They’d known each other so long. She almost smiled, thinking about how most of the people they knew couldn’t understand why they hadn’t married. But, of course, they could never marry. They were closer than a sister and a brother. They had grown up as outcasts who’d had to prove themselves, even to survive in the bawdy, salvaging, raw world of Key West, where nationalities mingled with the nationless pirates, and, yes, where the War of Northern Aggression went on, though most often as idle threats and fists raised to the sky. At Fort Zachary Taylor, the Union troops died far more frequently from disease than from battle, though Union ships ever tightened their grip on the blockade. Beer, wine, rum, Scottish whiskey and all manner of alcohol ran rich at the taverns. Fishermen mingled with the architects of the fine new houses, and only at night, behind the wooden walls of their houses—poor or splendid—did the system of class mean much in Key West.

Tara thought that she and Richard were far closer than they might have been had they been born blood sister and brother. Tara’s mother had returned from an excursion to the mainland with a new name and child, but no husband. Richard’s mother had deserted his pirating father, who had eventually been seized and hanged for his criminal ways. Lorna Douglas Fox had taken Richard in when he’d been just eight years old, ignoring all speculations that the boy would surely grow to be as bad as his father. Lorna had already weathered rumor and whispers; she didn’t care what people said, no matter how tiny the island community. She had been born in Key West, and her father had been there before Florida had even become a U.S. territory, much less a state. And, of course, at the beginning, statehood had meant little in Key West. Its population had remained Spanish, Bahamian, English and American … and that really only at shifting intervals, since so many came just to fish, drink and rest, and move on back to nearby island homes.

Tara stood. Richard eyed her warily but stood, too.

“Where is your ship?” she asked flatly.

“I haven’t dissuaded you at all, have I?”

She wagged a finger at him. “You have given me a lecture. Now, I shall give you one! I think—however he might have been hated in the South—that Abraham Lincoln is an incredibly good man. I believe that of many of our leaders and generals, as well. And, I think that we need him. I think that we’ll need many men of his ilk if we’re ever to repair the great rift that’s been created. As you said, John Brown might have been an out-and-out murderer, and certainly, by the law, his sentence was just, but he did have the right idea. Here’s where we are, though, about to surrender to a furious power that will have to have any remnant inklings of vengeance held in check, or else the South will be truly doomed. I have to try to get close to the man. I believe that he needs me—and that’s not turning traitor, because my state will need a strong, enlightened man in control when the giant foot of victory stomps down on us as if we were a pile of ants. Maybe God did decree that we lose the war, but I don’t believe that even God wants more horror than what we’ve already seen to follow it.”

Richard looked downward for a moment, and then met her eyes again. “I’m so afraid anytime you leave, Tara. Here … here, you’re safe. You have me—and even if I’m not here, you have the threat of me! You have people who know you and love you, and if the general population somewhere knew everything about you—or if they suspected the truth about you—we have stock! We have plenty of beef, we have … blood.”

THE UNION SHIP USS Montgomery found anchor in the deep harbor at Key West.

Soon the ship’s tender drew to the dockside entry of Fort Zachary Taylor on a crystal-clear winter’s morning, and Finn took a moment to enjoy the sun streaming down on him through a cloudless blue sky. Palms and pines lined deep-water accesses on the island and joined with the bracken that collided on small spits of sandy beach.

The fort itself was a handsome structure, joined to the island by a causeway that was equipped with a drawbridge. When the Union had first maintained the fort, there had been fears that the citizens of Key West would rise up and try to take it, hence the drawbridge, and the ten cannons set toward the shore. The walls were thick, and dominating the northwest tip of the island, the fortress was an imposing structure to those at sea.

However, despite these fears, it had yet to see real action in the war, and at this point, it was not likely to. Still, the fort had been a major player by enforcing the Union’s dominance of the shipping lanes. The Union blockade was strangling the South, and many of the men stationed at the barracks at Fort Zachary Taylor had been the sailors who prevented Bahamian goods and British guns from reinforcing the rebels.

Finn mused that, from the outset, the North had been at a disadvantage when it had come to true military genius, since many of the mainstays of the Union army—men who had fought and prevailed valiantly in the Mexican conflict—had chosen to lead the troops in their own states. An agrarian society, the South had naturally bred many fine horsemen, and their cavalry had been exceptional. But the North had the manufacturing, a greater supply of men upon which to draw and what Finn considered the key in finally winning the war: tenacity. That tenacity, of course, came in the form of the one man who stayed his course no matter how bitter and brutal and disillusioned many had become: Lincoln.

“Agent Dunne!” a smartly saluting soldier proclaimed, offering assistance with his travel bags. Finn greeted him in return, leaping upon the dock.

“I’m Lieutenant Bowers. We’ve been expecting you, sir! And, please, whatever you’ve heard about the island and the fort, don’t condemn us before you’ve had your stay. Winter is the time to be here. Though it can grow cold, the days are dawning beautifully! It’s not wet and humid like the summer, and mosquitoes are at a minimum. There’s hardly a man in the hospital ward, and we’re praying we’ll not see another summer of war, sir, so we are.”

“We can all pray,” Finn assured him.

“Come along, sir.”

The fort was impressive, Finn thought as they entered. The causeway and drawbridge gave it a bastion against the island, and its high thick walls and multiple guns aimed at the sea provided for a threat against invaders from the water. On the grounds, the barracks seemed clean and even bright in the winter’s sun, while within the walls, Finn was certain, there was ample space for supplies, ammunition and further arms. As they walked, Lieutenant Bowers pointed out the dorm-style rooms where many of the fort’s occupants slept, the guard stations and the desalination plant, supplying the fort with its own mechanism for providing clean, potable water.

“Started out with cisterns here, but the rain didn’t come as thought. Then the seawater came in and the salt started eating away at the foundations,” Bowers said cheerfully. “We expected much more difficulty from the population, but … well, the citizens may call themselves Southern as we’re in a state in secession, but the place was filled with speculators, fishermen, a few rich and a few down and trodden. None has risen at arms, and while the few moneyed families are careful to keep their daughters under close guard, most of our men have managed to carry on decent relations with the Rebels. Oh, there’s a bit of jeering and even some spitting here and there, but nothing too bad!”

“And yet, you know that some of the populace must be plotting,” Finn said.

“Sir?” Bowers asked.

Finn smiled at him. “Please. Those running the blockade surely sift right through here. In small boats, there are many ways to move undetected or unnoticed. Fishermen still make a living, rum is reaching the bars and taverns. It would be impossible to police every transaction taking place.”

“True, of course,” Bowers said. “But you’ll note the east and west martello towers across the causeway on the mainland, sir. We are not a huge garrison, but we do manage something of control. Our power, however, is on the sea. We’ve learned well through the years.”

“We’ve learned a great deal through the years,” Finn agreed. “Where there is a will, dedicated men will always find a way.”

Finn was led to an office in one of the wooden barracks constructed on the grounds. Bowers opened the door and introduced Finn to his commanding officer, Captain Calloway, and then left.

“Agent Dunne,” Calloway said, standing. The captain had the weathered look of a man long familiar with the sea, and the very fact that his skin had begun to resemble one of the state’s famed alligators made him a man well worth his salt to Finn. Here was no pretty boy, no educated rich man sitting in power through academic hobnobbing. He’d been on a hard ride in service to his country.

Finn wondered what the captain saw in him, since he seemed to be measuring his worth in return. Finally, Calloway indicated a chair. “Sit, Agent Dunne, please. I must admit, I was surprised to hear that you were coming, and I hope we’ll be able to help you. I find it incredibly curious that you’re here, when President Lincoln is at the capital, and that still, in the midst of mayhem, you’re willing to track down every threat, obscure though some may be.”

“There is no threat against the president we deem obscure,” Finn told him.

Calloway nodded gravely. “Yes, but … well, I’m sure that President Lincoln has enemies everywhere—North and South. There are those in his own camp who believe he should have let the secessionist go. Those who were furious over the draft—Hell, there were draft riots. He surely has political enemies. Quite frankly, I’m surprised you have enough men to cover all threats. But to come here …”

“Here, to this is faraway, other world, you mean?” Finn suggested. “I certainly see your point, but we’ve learned through the years to separate what is probably an idle threat—angry talk—from what may well be a concerted plot being put into motion. My superiors consider this plot by the blockade runners and their coconspirators serious. We have a man incarcerated in the capital now, and the correspondence he carried was damning. Better to stop the situation at the seed than allow it to become a giant tree with branches sweeping across the continent.”

“I see,” Calloway said, though Finn was pretty sure he didn’t really. “And yet, in truth, how easily the president could be stopped by a single bullet, while riding in his carriage around the mall …”

Finn didn’t want to admit that it wasn’t an easy task protecting the man. While Lincoln was plagued with strange dreams and a sense that his lifespan would be cut short, he seemed unwilling to take the necessary steps to prevent such an outcome. “In the capital, and when the president travels, he is still under protection. He has the military, and he has Pinkerton agents. Pinkerton himself stopped an assassination attempt in Maryland. We have men in the capital, and we have men covertly stationed throughout the Southern armies. Captain, the point is not just to be at the president’s side and stop individual bullets. It’s also to stop what could become an event in which many people are involved, if you will—a situation in which the entire government is brought down.”

“Like, say, a civil war,” Calloway said gravely, still looking puzzled, though introspective. “Do you usually succeed in these intelligence missions?”

“We do, sir.” Inwardly, Finn flinched. Usually. Usually, he discovered the truth of every situation. But he still chafed over one particular failure: the day he had lost the woman at Gettysburg. Ostensibly, she’d carried nothing but a harmless scarf. But there had been something strange about the beauty, something he felt he recognized and that portended danger. The memories of that day had haunted him since.

“Well,” Calloway said, “I’m not privy to your means of intelligence, sir, but we’re pleased to offer all the assistance that we may. I believe that you want to set out tomorrow night?”

“Indeed. The moon will be all but black, and I understand that this time of year lends itself to good cloud cover. If I were setting out with contraband and communications, it’s the night I would choose to take flight.”

“You’ll be sailing with Captain John Tremblay, an excellent sailor, and a rare man—a native of St. Augustine. And,” Calloway admitted, “he pointed out to me himself that the date you have chosen does seem optimal for such a runner to take flight. I hope, sir, that you are not on a wild-goose chase, and that you catch your man. May God help us all in this.”

THE WAR, EVEN IN DISTANT Key West where little happened, had changed life.

Tara could remember being a child when it was easy to run down to the wharf at any time, when a friend might head out fishing or just take sail because it was a beautiful day. She remembered shopping the fish market without tension in the air, and when the cats and seabirds shrieked and cried out, trying to steal the best fish heads and the refuse tossed aside by the men and women working the stalls.

She remembered when the great ships had brought in new supplies from the Northeast, the Bahamas or even Europe. Women on the island would receive their copies of Godey’s Lady’s Book, and they had oohed and aahed over the newest fashions and determined what they should buy, what they could sew and what they could practicably wear on an island where heat was king.

Some merchant ships still came, though they were heavily patrolled by the Union. Women still looked at fashions, but they could seldom afford to buy. The fish markets were quiet, with only the birds and the cats unaware of the unspoken tensions.

And it was no longer easy to set sail from the tiny island, not without proper credentials. Unless, of course, it was by darkness, in a small craft, and with someone who knew the lay of the land.

That being, Tara left the island of Key West on a single-mast fishing boat with Seminole Pete, who had long kept a bar in town. Pete had outlasted the Seminole Wars, and he had never surrendered or succumbed—he had just kept moving, and now his bar was a fixture. In his spare time, Pete “fished,” and in doing so he helped his friends, who numbered many. There were only friends and those who were not his friends. In his day, he’d seen half his people decimated in the Seminole Wars, and there was no white man in a uniform he trusted, North or South. Tara was Pete’s friend, and she loved that he was one of the few people who seemed to know everything about her without ever being told.

When Tara’s mother had died, just as the war had commenced, Tara had rented out the beautiful home on Caroline Street her grandfather had built, and took residence in a few rooms in the huge and rambling home Pete owned. Pete and Richard had both insisted she do so; it was dangerous for her to be alone.

That was fine with her. She’d always thought her mother would eventually marry Pete, but while the two were close and constantly together, they’d never taken vows. It was nice to be around him after her passing.

As they neared the small island just north of Key West, Tara became aware of the scents on the air: cows, pigs, chickens and other animals. The Union-held fort and the Confederate citizens of the lower Keys all found their sustenance through the remarkable resources of the island.

“We are near. You are in plenty of time,” Pete said, his voice expressionless.

Pete didn’t question the power of dreams; when she had explained to him that she felt that she had to get close to the American president, he merely nodded. He’d taken many a person through the years to Richard’s ship, hidden behind the mangroves. An Indian out in a small fishing boat was not someone with whom the Yankee troops would bother.

Besides, not even the Union troops questioned where Seminole Pete secured his beverages. Off-duty, they were far too pleased to enjoy his bar. In fact, at times, the situation there would have been comical if there weren’t a country pathetically at war all around them. Customers sometimes shouted taunts, or made them beneath their breath, but all kept it peaceful, as if they were but placing bets on different horses in a race.

She looked over at Pete. The sail was down, so he rowed steadily, his sculpted face impassive. He watched her as he steadfastly drew the oars, one easy, even stroke after another.

“You think I’m crazy,” she said quietly, breaking through the rhythmic sound of the oars on the water.

“You said you must do this. Then you must,” he said. “Will I worry about you? Indeed, child, I will.”

“Have you ever had anything like this happen to you?” Tara asked. “I mean, where your dreams were of someone else and came upon you like a sickness of worry?”

“I know many people who have had such dreams,” Pete said gravely. “But were they dreams? Or did we know that the guns were coming to our shores, and that we would be driven farther and farther into the swamps? Perhaps we rush to bring these things into our minds, and dreams are the culminations of our fear—fear for what we can’t stop.”

“But if we see omens, doesn’t that mean there’s at least a prayer we can stop a catastrophe?”

“Perhaps,” Pete said, gazing out across the darkness. “Sometimes we see a path, and think that we must take it, and then there’s a fork in the road. We may not go to the same destination.”

She smiled. “You’re confusing me, Pete.”

“Life is confusion. Now, more than ever. Or it is not. We just live. Time will come and go, and this war will end, and there will be new wars. I understand that any man or woman must do what they believe is asked of them by a great power. So, do what you must. And then come home. This is where you belong. Where you are known and where you are loved. There will be bitter days ahead, and harsh punishment, and our tiny island world will be far enough from the heaviest part of the boot when it falls.”

“The war isn’t over yet,” she half protested, though she didn’t know why.

“All but the tail end of the dying. Trust me—I’ve seen war. At the end, there is nothing but blood.”

“There is already blood,” Tara said softly.

Pete didn’t disagree; he had spoken his mind.

She was aware of the sound of the oars striking the water again and listened to them for a while. Then Pete nodded his head toward the horizon.

Squinting, Tara could see Richard’s Peace, sails down, at deep anchor off the stock island. It was barely a silhouette against the dark sky. She was surprised that Pete had seen it, but he had spent much of his life fighting and running through the darkness and the marsh.

Peace was a beautiful ship. Richard had commissioned her for his salvage and merchandising business before secession, and before he had ever dreamed of operating her as a war vessel. She had three masts and a square rig, which meant that at full sail she was quite a sight to behold. She could move swiftly over the open water, but since the decline of the clipper had begun with the advent of steam, Richard had modernized her by equipping her with a steamer, as well. She had a shallow draft, and could easily navigate the coral reefs and shoals, especially with a captain like Richard manning her; he knew the waters around the Florida Keys as well as he knew his own image in a mirror, if not better.

Richard had sailed out on a dark night many a time, evading the enemy ships. He hid the Peace and walked about Key West as an average citizen, avoiding the Yankee troops in the town these past four years.

Pete ceased to row, letting his small boat drift toward the larger ship. A man on guard on the deck quickly called down to them. “State your business, and speak quickly!”

“It’s Tara Fox!” she called quickly.

“Come aboard!”

A rope ladder was thrown down, and Tara leaned over to plant a kiss on Pete’s face. She imagined he might have blushed. “Don’t worry. I will make it home,” she promised him.

Grabbing her satchel and securing it around her shoulders, she reached for the rope and carefully climbed her way up to the deck. Richard was there to help her on board.

“You know, you are insane,” he told her huskily.

“Just following the lead of my captain!” she returned. He turned quickly, introducing her to the man on guard.

“Tara, I think you know Grant Quimbly here. Lawrence Seville is at the helm, and Gary French is working the steam engine. Make yourself at home in the cabin. We’ll be on our way.”

“Thank you, Richard,” she told him.

He nodded. “Lawrence, let’s get her under way!”

Tara looked down to the dark sea; she could barely make out Pete’s small boat.

The darkness seemed overwhelming.

But just as she thought so, the cloud cover shifted, and a pale glow of starlight filled the sky. She could see the barest sliver of a moon. It was the night of the new moon, and yet, it almost looked as if, for a moment, it was waxing crescent.

It almost appeared to be grinning.

She shivered. It seemed as if even the moon was mocking her.