Читать книгу Dangerous Dames - Heather Hundley - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION: PARADOXES OF GENDERED POWER RELATIONS AND REPRESENTATIONS

ОглавлениеPower relations are gendered, organizing bodies and relationships in significant ways—sometimes with devastating results. According to a report from the United Nations, one in three women worldwide has experienced intimate partner violence or sexual violence (“The World’s Women,” 2015). An alarming 41 % of transgender youth in the United States have attempted suicide (Haas, Rodgers, & Herman, 2014). Men—especially black men—in the United States are incarcerated at disturbing rates, most frequently for non-violent crimes (Wagner & Sawyer, 2018). Mass shootings continue to increase in the United States, and 98 % of perpetrators are white males (Follman, Aronsen, & Pan, 2018). The United Nations estimates approximately 70 % of the world’s poor are women, suggesting patriarchy disproportionately impoverishes female bodies (Abercrombie & Hastings, 2016). Each of these statistics reveals the material consequences of gendering power as cis, white, and hegemonically masculine. Nevertheless, increasing access to power is something we are taught to desire and strive to accomplish.

A ubiquitous concept often associated with physical or economic strength, power aligns with masculinity because men frequently possess stronger physiques. In a patriarchal, heteronormative landscape, economic power is gendered as masculine because men are awarded higher salaries, positioning them ←1 | 2→as household breadwinners in heterosexual relationships. Furthermore, they have greater access to corporate positions of power. The top 10 wealthiest people in the United States are men, and, according to the Associated Press (2017), “the eight individuals who own as much as half of the rest of the planet are all men” (para. 1). For example, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, known for his brute strength, chiseled features, and wealth, models the linking of power and hypermasculinity. Through success partly derived from his size and strength, he became Hollywood’s second highest paid actor, earning $65 million in 2017, and he is considering entering politics (Kelsey, 2018). Similarly, older generations witnessed Arnold Schwarzenegger transition from world famous bodybuilder to actor to politician, serving as California’s two-term governor from 2003 to 2011 and illustrating the entangled relationships (and stereotypically masculine associations) among physical strength, economic prowess, and political influence.

Although power is marked as masculine in many ways, contemporary society is not void of feminine empowerment. Just over 50 years since the beginning of the major civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s, including Civil Rights, Women’s Liberation and the second wave of feminism, the American Indian Movement, Chican@ Rights, the Farmworker’s Movement, and the launch of environmentalism and ecofeminism, we have witnessed positive strides for women in the United States. Victories such as the Food and Drug Administration’s 1960 approval of the oral contraceptive pill and the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade (1973) have allowed women to control their own reproductive rights, moving towards women’s status today. Additionally, though not yet fully actualized, the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 encouraged more women to enter the workforce.1 Recognition of sexual harassment and sexual assault has increased dramatically in the past 50 years, leading to contemporary agitation globally. With increased resources and legal protections available, more women attend universities and earn bachelor’s degrees, participate in all levels of government, fight in combat, and lead as business tycoons—venues where women were not permitted in the not-too-distant past.

Although women have always been strong and powerful, those who stand out as cultural icons typically have been the exception rather than the rule. For example, although female-bodied aviators abound (Haynsworth, Toomey, & McInerney, 1998), Amelia Earhart is the lone woman in aviation known widely prior to 1970s astronaut Sally Ride. Rosa Parks ironically takes a back seat to her male counterparts, including Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and ←2 | 3→Martin Luther King, Jr. Similarly, civil rights activist and labor leader Dolores Huerta is overshadowed by her co-founder of the National Farmworkers Association, César Chávez (Sowards, 2010, 2012). Media mogul Oprah Winfrey, touted by Forbes and Fortune as one of the world’s most powerful women, “is the only person in the world to have appeared in Time’s list of the most influential people 10 times” (Nearmy, 2016, para. 1). Yet, the ongoing prevalence of gender and race disparities in Hollywood continue to draw scholarly attention (Reign, 2018; Thompson, 2018).

Nevertheless, trailblazing figures have led the way for other strong and powerful women. Since the 1980s, female-bodied aviators and astronauts have become much more commonplace. Female-bodied politicians have increased, as well. For example, 39 women have served as governors in 28 states, 307 women have served in Congress, and 19 of the 100 largest cities in the United States have had female-bodied mayors (“A brief history,” 2016). Women’s presence has increased in the boardroom too, with 24 women leading Fortune 500 companies as CEOs. In 1981, Sandra Day O’Connor emerged as the first, and only, female-bodied Supreme Court Justice until Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined her in 1993. More headway has been made since 1/3 of the bench are women in 2019: Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. At the box office, Wonder Woman, directed by Patty Jenkins, set a new record for a movie directed by a woman in 2017. Such gains have ushered in, for some, the notion that we are now in a postfeminist era. The concept of postfeminism is “fraught with contradictions” (Genz & Brabon, 2009, p. 1), but it consistently denotes the perception that gender equality has arrived—or at least is well on its way—and therefore feminism is no longer needed.

We reject this depoliticizing, perilous viewpoint. Despite the advances made, much work remains at the forefront of feminist activism. For example, even though 59 different women have been to space, that pales in comparison to the 474 male astronauts who have made the same journey. In terms of politicians, the record number of female-bodied governors at any given time was nine in 2004 and 2007; thus only 5 % of the states in the country were governed by women. Similarly, women head only 5 % of Fortune 500 companies. Although Hollywood too is shifting, Patty Jenkins is only the second woman to be the sole director of any live-action movie with a production budget over $100 million (Domonoske, 2017).

In addition to continued underrepresentation in government, economics, and on screen, the gender wage gap in 2016 was 20 % and even larger for women of color, guaranteed paid maternity leave is not available in the ←3 | 4→United States, and the second shift persists, with many women still being expected to maintain household, childcare, and parental care responsibilities irrespective of having paid jobs. Indeed, the second shift has expanded into a third, as digital labor has expanded to fill women’s leisure time as well (Chess, 2010; Jarrett, 2016; Jones, 2016). Women are overlooked for career advancement more than their male colleagues. In academia, for example, even though women earn just over 50 % of the U.S.-granted Ph.Ds., only 38 % of faculty members overall are women; 46 % are assistant professors, 38 % are associate professors, and 23 % are full professors (Mason, 2011). Considering the occupation alongside family and parenting responsibilities, “across all disciplines, women with children were 38 percent less likely than men with children to achieve tenure” (Mason, 2011, para. 11). “Among tenured professors, only 44 percent of women are married with children, compared with 77 percent of men” (Mason, 2011, para. 14). Thus, even though women are making advances, constraints abound, as evidenced by the glass ceiling and pay gaps, the good-old-boys club, disparate family obligations, social expectations, and sexual harassment, among other obstacles.

Beyond these ongoing structural challenges, the advances made have sparked a backlash. Rising to fame for refusing to honor students’ requests to use their preferred pronouns, Jordan B. Peterson typifies this backlash (Bowles, 2018; Lynskey, 2018; Wilhelm, 2018). Bowles (2018) calls him the “custodian of the patriarchy,” noting his view that “order is masculine. Chaos is feminine” (para. 3). Wilhelm (2018) describes him as “best known for offending and outraging large numbers of people on television and the Internet over various fraught topics like transgender pronouns, gender roles, and identity politics” (para. 5). He has attracted a large following (and sparked some backlash of his own), exemplifying how outrage is deployed to try to protect the status quo and nostalgic imagined past. Women’s advances are perceived as dangerous, and folks like Peterson are actively trying to maintain patriarchal positions of power.

Despite these structural, material, and rhetorical efforts to retain patriarchal power relations, as a result of the 1960s and 1970s movements and ongoing activism, younger generations are exposed to powerful women in greater numbers than in the past. As roles for women have expanded in government and business, so too have roles expanded for women in mediated representations. Indeed, media companies have been quick to capitalize on feminist gains by casting female-bodied protagonists in roles traditionally reserved for males.

←4 | 5→

Such representations have ushered in a postfeminist media era in which “perniciously effective,” active, and overlapping cultural processes work towards the “undoing of feminism[s];” (McRobbie, 2004, p. 255). A number of scholars have traced postfeminist media’s defining characteristics (Gill, 2007, 2016, 2017; McRobbie, 2004; Tasker & Negra, 2007). Gill (2017) summarizes the features she first identified in 2007, including

the notion of femininity as a bodily property; the shift from objectification to subjectification; an emphasis upon self-surveillance, monitoring and self-discipline; a focus on individualism, choice and empowerment; the dominance of a makeover paradigm; and a resurgence of ideas about natural sexual difference. (pp. 615–616)

These characteristics have only intensified as postfeminism has expanded and reified, to the point that Gill suggests postfeminism now acts as a “gendered neoliberalism” (p. 620). This has led to postfeminist representations of women who are sexually liberated, reject feminism, or occupy positions of power in “men’s” milieu, including sports and the military.

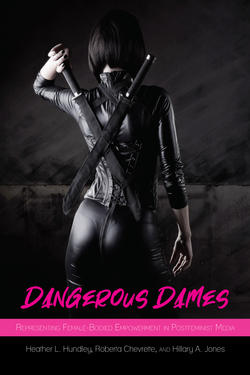

As feminists, we seek to illuminate the rhetorical work performed by contemporary representations of a specific type of postfeminist hero who has garnered a cache of cultural capital: the contemporary female-bodied action hero who is smart, capable, physically agile and fit, accomplished in her career, and proficient with weaponry and technology. We recognize that gender exists on a continuum, including nonbinary and trans experiences and expressions. Our use of the term “female-bodied” as well as “women” in our analyses is not to privilege a harmful and exclusionary biological definition of gender. Instead, our use of these terms is intended to reflect slippages between sex and gender in the popular imagination, and especially in the media construction of dangerous dames.

Fierce, frequently sexy, often feminine but sometimes androgynous, these heroes take no shit. Not only are their female bodies a focal point for their construction as strong and exceptional action heroes and women, but they are also frequently characterized by presumptions regarding biological “essences.” It is precisely this conflation of sex and gender that we seek to illuminate and problematize as we examine constructions of gender routed through sex stereotypes. We note that persons of all genders, sexes, and sexualities are affected by the subject positions proffered by these texts; the gendered exclusions within the rhetorical construction of the “female-bodied” warrior are thus at the heart of our analyses. Examining examples of these representations over the last quarter of a century and across media, we ask: what equipment ←5 | 6→and constraints emerge from these portrayals of dangerous dames with greater access to power? Do women exhibiting these powerful characteristics provide us with new or unique equipment for living and feminist ways of being? What complications or contradictions arise for meaningful feminist action via these mediated representations?