Читать книгу This City Belongs to You - Heather Vrana - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

The Republic of Students, 1942–1952

We have weapons that our forebears did not want, or were unable or were unwilling to wield . . . Three weapons that, well-used, can transform a group of guys . . . into a formidable force, capable of opposing and overthrowing those with the bayonets. These three weapons are our youth, our intelligence, and our unity.

“The Escuilach Manifesto”1

BANANAS—ON THE STALK, by the bunch, peeled, held aloft, all of them long Cavendish bananas grown for export by the United Fruit Company (UFCO)—formed the masthead of the No Nos Tientes in 1949. The anonymous artist was probably Mario López Larrave, a law student who drew most of the newspaper’s cheeky cartoons for many decades. The letters offered a visual complement to the pages of tongue-in-cheek text that appeared below them. After an “N” made of Guatemalan bananas destined for North American stomachs, a portrait of Francisco Javier Arana formed the “O” of Nos and two interlocking sickles formed the “S.” In April 1949, the young illustrator could not have known the prescience of his figures; rather, he drew from the anti-imperial spirit of the 1944 revolution that had been so crucial to his own academic and political formation. Within months, however, one member of the revolutionary junta would be assassinated and anticommunist hysteria would begin to ferment and, ultimately, alter the course of the nation.

López Larrave was just fifteen years old when M41 bulldog tanks closed in on the National Palace and finally deposed dictator Jorge Ubico y Castañeda (1931–1944).2 If school had not been cancelled, López Larrave and his classmates might have watched the action from the window of their classroom at the National Central Institute for Boys (INCV), just a few blocks away. Months earlier, a broad movement of university students, young military officers, teachers, workers, and women’s organizations had forced Ubico to end his thirteen-year dictatorship. For as long as many could remember, the pleasures of daily life, like intellectual exchange, art, music, politics, and even social gatherings, had been strictly regulated. Ubico, an alumnus, even influenced the boys’ INCV curriculum through his friendship with the school’s principal. Protests continued while Ubico’s handpicked successor, Juan Federico Ponce Vaides, remained in power. The city was seized by democratic fervor, inspired by Rooseveltian democracy and Central America’s unique historical moment.

Seen from the windows of INCV, the National Palace was a symbol of Ubico’s absolute power and utter decadence: an imposing baroque structure with a grand entryway, dozens of porticos, 350 rooms, numerous patios, and expansive hallways. Nearby, Guatemala’s urban poor suffered under laws that demanded their labor for export production and infrastructure construction. The 1934 vagrancy law required all men who lacked an “adequate profession” or proof of landownership to work between 100 and 150 days on massive rural plantations. Another law required all men—except those who could pay a fee—to work for two weeks per year building and maintaining roads. In business and politics, Ubico promoted his friends and family while he limited the opportunities available to others. A growing number of professionals and military officers were unable to advance in the careers for which they had trained.

Outgoing, earnest, and generous, López Larrave was a leader among his peers at INCV. The political opening that came with Ubico’s overthrow gave López Larrave’s enthusiasm a certain direction. At INCV, he met an outspoken university student leader named Manuel Galich who replaced Ubico’s crony as school principal. For the boys, Galich was larger than life. López Larrave’s classmate Roberto Díaz Castillo remembered, “the first time I heard him . . . the first time that his words—the Word of the revolution—shook that patio filled with adolescents who did not wear the military uniform, we saw in Galich our archetype of a popular hero.”3 For López Larrave, Díaz Castillo, and others of their generation, the revolution offered opportunities that had been foreclosed for many decades.

This chapter begins with Galich, and then expands to examine the political, social, and economic changes brought by the Revolution and their impact on university students and faculty. Throughout, I emphasize how San Carlistas’ debates over the meaning and practice of democracy reveal a particular understanding of cultural fitness as the engine of national progress. These conversations helped to define urban ladino intellectuals as they limited the civic participation of Guatemala’s indigenous majority. Constitutional reforms extending the franchise, education and social welfare reforms, and university research on indigenous communities and poverty were notable moments when these discussions came to the fore. Simply put, universitarios saw themselves as the Guatemalans most fit to determine the direction of the nation even as they fiercely debated the role that the university ought to play in society. Both on campus and off, terms like patria and libertad came to signify society’s most important qualities. Over time, this attitude became a signature of the Guatemalan middle class, as much as discretionary spending, leisure time, and social prestige in the community. For Guatemalans, as for other Latin Americans in the twentieth century, the middle class was celebrated as the key to a redemptive future, as it was critical to modern prosperity and a model of public virtue.4 During the revolutionary decade, discussions about the meaning and practice of democracy set the stage for the emergence of fierce anticommunist opposition and, soon, counterrevolution.

This chapter also captures some of the texture of daily student life in the 1940s. Student newspapers that printed satire, silly jokes, song lyrics, and comics remind us that in addition to adeptly discussing matters of state, San Carlistas were also pretty funny. Memoirs also fill in some detail—the elation of boyhood, teenage levity, and the self-consciousness of one’s later adult years—in a period that has left relatively little to the archival record.5 Much of this chapter draws on Del pánico al ataque by Manuel Galich. Galich published his memoir in 1949, five years after the success of the revolution and five years before counterrevolutionary forces would depose Jacobo Arbenz, who had not yet been elected. Like so many memoirs, it is uncritically inflected with triumphal hindsight.6 Galich presents himself and his friends as unified underdogs chasing fate, even as their diverse paths after the revolution are enough to call this unity into question. Nevertheless, the text offers insight into the hopes, dreams, and flaws of Galich’s generation. His nostalgic playfulness evokes the spirit of student nationalism.

In the first years of the Revolution, universitarios built a sense of fraternity, a political kinship, defined by affinities and exclusions. Women were important to the young men as wives, sisters, cleaners, cooks, and secretaries, but they were rarely classmates. Although women had attended the university since the 1920s, they were denied the fellowship and opportunities of male students.7 Likewise, indigenous students had never been excluded from the university, but they usually appeared in student papers as objects of ridicule or patronizing care because of their presumed lack of education. The impact of these exclusions expanded as the university’s influence over urban life extended. The reformed Constitution of 1945 bestowed new rights and responsibilities upon the whole education system. Teachers and students were to protect and expand culture, promote ethnic improvement (“promover el mejoramiento étnico”), and supervise civic and moral formation; in effect, to make the people fit for self-government.8

UBICO’S DECADENT FACTORY OF PROFESIONALISTAS

President Ubico lived and ruled in the manner of his idol, Napoleon Bonaparte. He dressed exclusively in military regalia, enjoyed motorcycle tours of the countryside and city, and hosted opulent dinners. Famously unpredictable, Ubico threw vicious tantrums as regularly as he threw galas.9 Politics at all levels operated under his control. Ministerial appointments reflected the interests of wealthy landowners, foreign investors, and Ubico’s friends and allies. At the local and regional level, Ubico eliminated challenges to his authority by hand-selecting intendentes to replace elected mayors in towns nationwide. Lest these intendentes become loyal to their communities, Ubico regularly moved them from place to place.10 Even Ubico’s nominally beneficent labor reform, which replaced debt peonage with vagrancy laws, empowered intendentes.11 The extraction of labor from poor men and women was crucial in years when global economic depression drove coffee prices so low that the commodity was scarcely profitable to produce and difficult to sell abroad. At the same time, Ubico deftly allied poor ladino and indigenous citizens to his government through powerful discourses of nation making and progress.12 Within the Army, Ubico based promotions on loyalty rather than competence. Over time, the officer class grew to resent these appointments and their incompetent superiors. Those who offended Ubico were punished and those who praised him lived well. These limitations paired with economic and infrastructural growth created the conditions for growing antipathy toward Ubico’s rule, especially among a small group of educated urban professionals and Army officers.13

The only sector that escaped Ubico’s punishing hand was Guatemala’s agricultural elite, especially UFCO, a Boston-based company formed in the last decades of the nineteenth century by the merger of banana production, distribution, and communication networks. UFCO agreed to build infrastructure in exchange for enormous land grants and preferential treatment: the company that would control one-third of the world’s banana trade by the 1950s paid very little in taxes to the Guatemalan government and was permitted to manage its workers with impunity. Of course, growth in export production and distribution networks required a large and skillful middle class.14 Huge companies required managers to organize workers, accountants to administer finances, lawyers to provide legal counsel and oversee contracts, and engineers to implement technical innovations. Dangerous plantations needed doctors and nurses to staff their hospitals and clinics. Supply shops required more accountants and managers. Children required schoolteachers.

Ubico adapted the National University to fulfill these needs. Like rural banana plantations, the urban university that churned out credentialed graduates was called “the decadent factory of profesionalistas.”15 This description of the university as factory is especially grim given Guatemala’s bleak labor landscape. Yet if the university was a decadent factory, it was so only for those who went along with the boss. Early in his presidency, Ubico granted himself control over the highest governing body at the university, the University High Council (CSU). From this position, he personally supervised all aspects of university life, including the very comportment of students and professors. Behavior and character became important parts of the curriculum. The institution was transformed from a center for scientific investigation and professional formation to a school of good manners. Galich, then a student, wrote that Ubico “wanted to form the minds of all Guatemalans . . . from philosophy to saddlery, and including science, law, ethics, economy, [and] motorcycling.” He joked that Ubico saw himself as “a walking encyclopedia with epaulets.”16

The belief that the university ought to stay out of national politics governed university affairs. As in other areas of government, Ubico hand-selected the university’s rector, deans, and secretaries for their allegiance rather than their proficiency. Deans were rarely experts in the fields that they advised, even though they made hiring and curriculum decisions. The rector retained final say over any faculty hires, but that position was also a presidential appointment. Faculty who opposed Ubico stood little chance of success. Ubico isolated the National University from other Latin American universities, despite interest in international student federations since the 1920s and more recent initiatives by students and faculty to unify Central American courses of study. Outside influence was suspect.17 In his memoir, Galich evoked the “suspicious grunt of the police chiefs when one asked permission to organize a conference, to receive an illustrious houseguest, [or] to form an indigenous institute,” even, he added, “to play chess . . . to coordinate an athletic tournament, to go to a library to read silently.”18

In early 1942, students from the Faculty of Law began to circulate critiques of the government in newspapers and pamphlets.19 Many of these statements were loosely transcribed in Galich’s memoir. The group criticized how the intellectual sector “has frequently been in the service of the dictator, of the autocracy” and “other times it has been rashly divided by differences in caste, religious convictions, by conflicting personal interests.”20 The young men warned of the danger of this disunity that left academics vulnerable to the power of despots. The group itself included brothers Mario and Julio Cesar Méndez Montenegro, Hiram Ordóñez, Manuel María Ávila Ayala, Heriberto Robles, Antonio Reyes Cardona, José Luis Bocaletti, José Manuel Fortuny, Alfonso Bauer Paíz, and Arturo Yaquian Otero. Most of these young men came from similar backgrounds: they were born or had spent most of their lives in the capital city and lived with parents who could afford expensive preparatory schooling for their sons. Ávila Ayala was different. He was about ten years older than his colleagues and was from Jalapa. Despite being a distinguished student, he never achieved the title of Licenciado, so valued in Guatemalan society. His bachillerato degree only certified him to teach handwriting and calligraphy. Like Ávila Ayala, Fortuny was also from the periphery and never graduated with a law degree. Instead, he quit school and worked for a North American business, Sterling Company. By contrast, Bauer Paíz, one of the youngest of the group, graduated from university by the end of 1942. He had attended the especially elite Colegio Preparatorio, unlike his fellows who had mostly attended the INCV. Mario Méndez Montenegro and Ordóñez had studied abroad. None of these young men were indigenous and most claimed some European ancestry. Most had been friends before university, like Bauer Paíz and Yaquian Otero who ran and lifted weights together because they wanted to lose weight before starting college.21

These young men who studied, ate, drank, and worked out together began to expand their conversations beyond the classroom by 1942. They called themselves the escuilaches, a term that lacks a singular history. It may be a reference to Spanish anti-French riots in 1766 or a pun on esquilar (to shear) and esquilador (sheep-shearer). The escuilaches were young men who wanted to shear the wool that Ubico had pulled over the eyes of the Guatemalan people.22 In any case, the escuilaches and their classmates were heirs to the political culture that celebrated the university’s role in Guatemalan political life that I outlined in the Introduction.

However, this history was discordant with their lives in Ubico’s Guatemala. At first, the escuilaches limited their critiques to the university administration. They denounced the appointment of ignorant deans and the dismissal of skilled faculty. They decried the lack of intellectual freedom. Soon they linked these grievances to national political and economic circumstances. They equated the university’s reigning principle of apoliticism to global fascism and blamed apolitical intellectuals for both world wars, arguing that a just society depended on an active university.23

In the middle of the night on May 15, 1942, the escuilaches snuck into the offices of the Third Court of the First Instance, the former home of President José María Reyna Barrios (1892–1898). They gathered to read what Galich calls in his memoir, “The Escuilach Manifesto.” In a romantic passage, Galich recounts the “dim azure light” of the moon where the young men realized their potential: “We have weapons that our forebears did not want, or were unable or were unwilling to wield . . . Three weapons that, well-used, can transform a group of guys . . . into a formidable force, capable of opposing and overthrowing those with bayonets. These three weapons are our youth, our intelligence, and our unity.”24 Galich’s reverence and hindsight intensifies the intoxicating promise of the moment.

His transcription of the manifesto includes an emotional account of the spiritual suffering Guatemala’s youth as a result of persistent despotism and greed. He writes that “the youth of Guatemala has never had teachers, ideologues, leaders who spoke to them of the destiny of the nation with a true heart, as Sarmiento and Alberdi spoke to the youth of South America, or Martí and Hostos, to the Caribbean youth, or, finally, Ingenieros to those of America.” Galich continues, “We have never known an apostle who did not appear later as a puppet, of a thinker who was not an imposter; . . . And what lessons do these teachers of pillage and assassination leave us? They are too bloody to mention.” The manifesto reflected the students’ transnational intellectual formation by Caribbean and South American positivist forefathers Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Juan Bautista Alberdi, José Martí, Eugenio María de Hostos, and José Ingenieros, even as it also asserted their isolation. Galich’s recounting of the manifesto continues, “If we think about this [we will] understand the eagerness with which the young Guatemalan impatiently awaits someone who will tell him the words that he is wanting to hear, the words of inspiration, of truth, of practical science, of legitimate patriotism, backed up by facts and not by lies.”25 In Galich’s retelling, the “young Guatemalan” becomes the figure for the whole of the nation, awaiting someone who can refine him with inspiration, truth, science, and patriotism. Galich writes that the group tiptoed out of the building with “the sensation of new breath in our souls.”26

Despite their enthusiasm, the young men were patient. While they aimed to prepare students to lead “a large popular movement that [would] destroy from the roots the old institutions and bring about a radical transformation,” they estimated that revolution was around ten years away. In the months after the scene described above, the escuilaches began by building support within the Faculty of Law. In October 1943, they revived the defunct Association of Law Students (Asociación de Estudiantes El Derecho [AED]).27 Following the AED’s example, a number of other facultades founded or revived student associations before the 1943 Christmas recess. Soon, several of these groups banded together into university-wide federation. The group took the name of the Association of University Students (Asociación de Estudiantes Universitarios [AEU]), the student federation formed in 1920, an earlier moment of groundswell in student organizing across Latin America, including Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Uruguay, and Cuba. The formation of a university-wide student group with its own bylaws and juridical norms changed the shape of inter- and intra-facultad relationships. The AEU of the 1920s imagined that university reform would follow after broader national reform, and so focused its energies outside of the university on the Central American Unionist movement. The revitalized AEU of the 1940s, by contrast, focused first on internal concerns.28

Nevertheless, it was the AEU of the 1940s that would most change Guatemalan society. Their first demand was to replace Ubico-appointed administrators with more prepared candidates. In the Faculty of Medicine, students succeeded in replacing Dean Ramiro Gálvez and his secretary Oscar Espada with Antonio Valdeavellano and Alfredo Gil.29 Students in Pharmacy followed suit, demanding new administrators and permission to participate in curriculum reform. Amid these early successes, the AEU struggled with a question that would divide the student body for the next six decades: what was the role of the university in politics? One block of medical students refused to join the AEU because they rejected the group’s involvement in national concerns, limited as it was. Even AEU president Alfonso Marroquín Orellana advocated a limited role for the university in national and citywide affairs. The escuilaches could not disagree more. By September, the avowedly political escuilaches had expanded their influence in the AEU and replaced the apolitical Marroquín Orellana with fellow escuilach, Gerardo Gordillo Barrios.30

As historian Virgilio Álvarez Aragón has noted, joining students across facultades enabled the group to exert political power and influence outside the university.31 For his part, Galich wrote that students found in the new organizations “the democratic exercise that [they] were denied as citizens”—political expression, assembly, and representation.32 Before long, opposition to Ubico became major point of cohesion among groups that had begun with more disparate and modest aims. The AEU had come to represent “the recapture of student rebellion” or, as Galich’s title suggests, “the end of panic and the beginning of the attack.”33

In May 1944, two events encouraged the AEU to go on the offensive. The first was the overthrow of Salvadoran dictator and Ubico crony Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. University students had been instrumental in the dictator’s overthrow, and their Guatemalan counterparts saw this as a victory of the student spirit. The AEU sent a letter of support signed by nearly two hundred students who professed their “faith in the dignified future of our Central American pueblos.”34 We can assume that this was a sizeable percentage of the student body, as enrollment was just 711 students in 1943.35 The second event that catalyzed university students was the incarceration of their classmate, Ramón Cadena. Arrested on charges only vaguely recorded as “political,” Cadena was held in the Central Penitentiary for weeks without due process. Galich and other law students wrote a letter of protest to Ubico on June 12. The letter accused the military tribunal of conducting a false trial and prosecuting Cadena’s personal views rather than the facts of the case. Like the letter of support for Salvadoran students, this letter circulated through the university and gathered dozens of signatures. But before it could reach the hot-tempered dictator, the National Police intercepted the petition. Cadena was released. Students celebrated this as a victory and the student body gained, according to Galich, new “confidence in itself and in its unity.”36

Ubico’s desperation also grew. Repression had been the order of the day for more than a decade, but the detention of visiting scholars, repression of student meetings, interrogation of student leaders, and dismissal of professionals who spoke out of place were committed with greater boldness. Ubico fired Ávila Ayala from his post at INCV. Galich wrote that Ávila Ayala was fired because he asked students to apply knowledge from inside the classroom to question the world outside, precisely the kind of teaching that Ubico despised. Of course he was also an escuilach.37 Reflecting on their audacity, Galich wrote, “we did not know even remotely then, but we already sensed [it].”38 Opposition to Ubico swelled. Students would no longer simply endure.

FROM STRIKE TO REVOLUTION

On the afternoon of June 19, 1944, the AED assembled for a business meeting. The group counted about a hundred students, just under half of the facultad’s total enrollment, though even fewer usually attended meetings.39 But this afternoon, the assembly hall filled with hundreds of students and professors from other facultades, and teachers and other professionals. The crowd presaged an extraordinary turn of events. Perhaps people came to hear the results of the AED elections, which pitted an escuilach against an apolitical candidate. More likely, they anticipated something more. As the meeting began, copies of a letter circulated through the crowd. The letter demanded the dismissal of the new Law facultad dean and secretary, both recent Ubico appointments. This was an aggressive, but not unprecedented, challenge to Ubico’s authority. After all, students in the facultades of Medicine and Pharmacy had made similar demands earlier in the year. But this letter went one step further and proposed two suitable replacements. The letter effectively asserted that the students, not Ubico or his hand-selected faculty, should choose administrators. The letter circulated and the meeting continued.

Then, just as the announcement of the results of the AED elections began, two students proposed a general strike. A roar of excitement filled the room. “Of the passive students of the previous fourteen years, there remained not a whit,” remembered Galich.40 The AED leadership resumed the meeting and announced the election results: escuilach Mario Méndez Montenegro was elected AED president, Hector Zachrisson as vice president, Manuel Galich and Carlos González Landford as secretaries, and Oscar de León Aragón as treasurer. After a round of applause for the newly elected leaders, the crowd again erupted with a motion to strike. Galich remembered, “A ‘hurrah!’ sprang from more than two hundred young but virile throats, and applause rang out through our ‘first minute of the liberation.’”41 They planned a meeting for the following day to give the whole university an opportunity to consider the strike declaration and the AED student leaders time to work out the details. For many decades, San Carlistas would define themselves and their social class through a contentious relationship between the student body, the university, and the state. These early assemblies were the first shouts—hardly whispers—of the struggles to come.

The next day, an even larger group gathered. It was one of the first times in decades that large numbers of students of medicine, law, economics, and engineering had gathered as a group. Representatives from the various facultades took the dais and expressed their support for the strike. The group also voted to unconditionally support the capital city schoolteachers’ strike against Ubico’s education minister. The alliance was practical, as many students like Galich and Ávila Ayala taught at capital city secondary schools while finishing their degrees at university.42 Galich remembers that he and Ávila Ayala left the meeting together and walked from downtown to their homes in the southern neighborhood of Campo Marte in Zone 5, about a three-kilometer walk. They discussed the rising protest as they walked. Anticipating that Ubico would seek retribution, they decided to write two documents: a public declaration of unity between schoolteachers and universitarios and a clear statement of the ideology of the group, an Ideario. The declaration of unity would protect both groups and improve the students’ reputation. The Ideario would clearly articulate the group’s ideals, in case Ubico judged them to be seditious.

First, the Ideario affirmed that administrators and teachers should not be bureaucratic appointments, but rather selected for their academic background and commitment to the university. Second, it argued for the removal of administrators who did not conform to this standard. Third, it prioritized the development of scientific and technical knowledge at the university. It also called for the foundation of a Faculty of Humanities and a research institute on indigenous history and language. It acknowledged students’ desire to participate in policy making at the university. Finally, it called for the government to work closely with students to improve the international reputation of the university through scientific and cultural publications and by reinstating the foreign exchange program. The demands sought to recover the National University’s historic prestige and reorient its activities toward national improvement. Inspired by classical liberalism with a rights-bearing student at the vanguard, the Ideario closed with a declaration that the students’ only interest was the “creation of the ideal university.”43 In sum, it articulated professionalism, study, and encounters with state bodies and institutions as the first expression of student nationalism, which would become the most enduring feature of Guatemala’s middle class.44

Galich’s memoir recounts a remarkable meeting that was held the following morning. Galich, Mario Méndez Montenegro, and Zachrisson were summoned to Ubico’s chambers. His personal secretary, Ernesto Rivas, received the young men and began the meeting with an offer: Ubico would dismiss his recent Law School dean and secretary appointments if they promised to call off the strike. Galich remembered that the young men responded, “We could comply with this agreement, but we cannot speak to whether our colleagues would approve a decision that is personally ours” and Méndez Montenegro confirmed, “In no way can we decide something for the entire University.”45 The students’ collective-minded response may have been surprising to Rivas, who was accustomed to Ubico’s autocratic style. Negotiations continued, though the young students did not budge. At one point, the telephone rang. It was Ubico. After he hung up, Rivas offered even further concessions to the students. In fact as the morning wore on, he offered concessions to all of the students’ demands: the replacement of the recent appointments, the formation of a Faculty of Humanities, and even Ávila Ayala’s reinstatement at the INCV. At the nearby Paraninfo, students, professors, and teachers waited for news from the meeting. Five hours later, Galich, Méndez Montenegro, and Zachrisson left the National Palace for lunch.46

The three men, all in their early 30s, had been invested with tremendous authority as liaisons between the emergent student movement and the dictator. Now, they had to decide whether to present the assembled crowd with the Ideario, the president’s concessions, or both. Galich remembered that they met with friends at the cafeteria of the judicial office buildings to discuss the situation. They ordered lunch from Miss Chaíto, a woman Galich remembered as the “guardian angel of the students who worked at the courts in those years,” who served the students “not only with efficiency, but also with affection.”47 While fighting for a more just future, Galich and his peers relied upon the manual labor of others, especially the affective labor of women in service positions. We cannot precisely know Miss Chaíto’s motives, but we do know that women whose histories have not become iconic also opposed Ubico. Perhaps Miss Chaíto’s labor was a political act in itself—providing support for the overthrow of Ubico—rather than the act of personal affection that Galich recounted.

Over beef stew, avocado, tortillas, coffee, and bread, the young men argued. Galich advocated for a more restrained approach. He was concerned that the embryonic movement might be unable to sustain a struggle against the dictator. Further, if Ubico had agreed to their demands, why should they continue to fight? Méndez Montenegro disagreed. As long as Ubico remained in power and the university was not autonomous, their demands remained unfulfilled. The movement could only gain momentum. Finally, he lost patience and, according to Galich’s memoir, “stood up and leaned across the table, pointing his finger at me, saying in a decisive tone: ‘If you back out now, escuilach, I am going to punch you!’” Galich, it seems, found new resolve. They would not accept Ubico’s concessions. The young men returned to the National Palace. In Galich’s words, “impulse triumphed over caution; intuition overcame reason.”48

The three students returned to the Paraninfo, which by that time overflowed with “students, teachers, people of all social classes, of all professions, of all of the neighborhoods of the city, who came to witness a accomplishment without precedent in Jorge Ubico’s Guatemala.”49 Applause and cheers erupted as Galich reported how Ubico acceded to all of the group’s demands. Another student stood to read the Ideario. Cries of “Viva!” filled the room and it was unanimously approved. Celso Cerezo Dardón suggested a general strike. Others urged the group to wait and see whether the president would issue a formal response to the Ideario. The meeting dissolved into muddled debates and disagreements. Then, in Galich’s cinematic retelling, a young student, barely out of secondary school, stepped forward and yelled, “If you don’t declare the strike, I will declare my own strike!”50

The strike was on. Over the next few hours, representatives from each facultad made speeches and listed demands. Students in laboratory sciences demanded better equipment, other facultades demanded technical schools for workers and a School of Pedagogy.51 That their demands hardly differed from those pursued by students in the early 1920s confirmed the university’s stasis during the dictatorship. After some debate, the group agreed to give Ubico twenty-four hours to comply. Before the meeting adjourned, a group of young lawyers joined the strike. Now the striking students had support from two important professional sectors, education and law.

After the meeting, the escuilaches assembled at Ávila Ayala’s house to prepare the long list of demands to be delivered to the president. The young men talked, smoked, typed, and copyedited. On breaks, Galich remembers how they retired to a different room to consult a fortune-telling toy. Regrettably, these fortunes are lost to history.52 The following morning of June 22, Cerezo Dardón delivered the demands and the Ideario to Ubico. Galich remembers that he tried to sleep late, but his daughter’s cries woke him. Unable to rest, Galich went to meet with friends in the offices of the Third Court. His sleeplessness was a stroke of luck, as policemen came searching for him soon after he left. Ubico had ordered the arrest of the student leaders. He had also suspended the constitution. Friends smuggled Galich, Ávila Ayala, and Méndez Montenegro into the Mexican Embassy, where they joined nearly all of the students, teachers, and lawyers who had signed the strike declaration.53 The group anticipated arrest, exile, or worse. They waited to see how the rest of the nation would respond. An answer came later that afternoon in a treatise entitled “The Document of the 311.” Named for its three hundred-eleven signatories, including many professionals and high-profile academics, the document called for an end the state of exception and the reinstatement of the Constitution.54

Hand to hand and by word of mouth, the demands, the Ideario, and other declarations, slogans, and plans circulated throughout the capital. Small protests punctuated daily life over the next three days. The Ubico regime responded by sending parapolice forces into neighborhoods to loot and attack residents. The protestors were blamed for damages and injuries.55 On the afternoon of June 25, a group of schoolteachers organized a protest at the Church of St. Francis, located five blocks from the National Palace. Their chants and signs demanded freedom, democracy, and Ubico’s dismissal. Memoirs and journalistic accounts of the protest emphasize that the women were well-dressed, professional, and orderly. This was important to the opposition’s claim that the imminent attack was unjustified. Ubico ordered the military and police to enclose the protestors. Officers fired shots into the crowd and one young teacher, Maria Chinchilla Recinos, was struck and died in the street. For many, this attack against a teacher—a professional woman who nurtured the nation’s children—was unforgiveable. Emboldened, workers’ groups came forward to join the strike and Ubico’s regime lost what little support it had from small business owners who depended on him to curb worker unrest. According to the Foreign Broadcast Information Service, by the end of June, Guatemala seemed to be “on the verge of a revolution.”56

Like others who had openly opposed Ubico, Galich, Ávila Ayala, Méndez Montenegro, and Cerezo decided to go into exile in Mexico as the situation deteriorated.57 In fact, they were on a train to Mexico City when the conductor announced Ubico’s resignation.58 Only eight days had passed since the young men had met with Ubico’s secretary. Galich wrote, “It was as if a frenzy overtook us. We hugged. We squeezed one another for a long time. We drank every beer on the train. Some mariachis accompanied our celebration with songs from the Aztec land.”59 The young men’s Mexican exile became a sightseeing holiday. The group went to the Museo de Bellas Artes, visited a secret aguardiente factory, and met with Mexican university students. To Ávila Ayala’s dismay, they even saw a bullfight. He despised the fiesta brava and spoke, Galich wrote, “in the name of some hypothetical society for the protection of animals—‘I don’t know how you can applaud such savagery.’”60 The young men returned to a hero’s welcome. Apparently, Galich was embraced so enthusiastically that his trousers fell off.61

Two weeks later, Ubico’s handpicked successor, Federico Ponce Vaides, was sworn in as interim president. Elections were scheduled for mid-December, but Ponce’s dictatorial intentions were clear from the outset. Opposition continued to grow. The AEU sent more demands and petitions to the National Palace. To their earlier demands, they added the reinstatement of all public employees who had been fired for participating in the anti-Ubico strikes, the removal of police from all university buildings, the retraction of threats made against teachers, and respect for “democratic rights.”62 They also demanded university autonomy. In short, Ubico’s resignation did not bring order, but instead emboldened the opposition.63 Ponce maneuvered between the protestors’ and his predecessor’s expectations, but had little success in satisfying either. For instance, when students convened an all-university congress to assemble a list of acceptable candidates to replace the university’s Ubico-appointed rector, Ponce was all but forced to accept one of their suggestions, Carlos Federico Mora.

Ponce also faced competition in upcoming presidential elections. Two new political parties emerged out of the anti-Ubico strikes. Schoolteachers and professionals formed the National Renovation Party (Partido Nacional Renovador [PNR]) on the day after Ubico stepped down. They selected their candidate for president that same afternoon: distinguished professor and doctor of education Juan José Arévalo Bermejo. Arévalo, like many other capital-city-born intellectual elites, had spent many years abroad at university or in exile, and sometimes both. He had attended the National University for a short time before going to Paris. From Paris, he went to Argentina on a scholarship to study education, where he finished a PhD. In 1934, he returned to Guatemala to serve in the Ministry of Education but returned to Argentina two years later after conflicts with Ubico. Students formed another party, the Frente Popular Libertador (FPL).64 The FPL nominated AED president Julio César Méndez Montenegro as their candidate and National University alumni filled his cabinet. In August, however, the group joined the PNR to form the Revolutionary Action Party (Partido de Acción Revolucionaria [PAR]) and back Arévalo. Méndez Montenegro would have to wait until 1966 for his turn as president. Many things would change by that time.

Meanwhile, Ponce’s regime showed more signs of stress. Public protest continued in the capital city. Critics of Ubico, like Luis Cardoza y Aragón, began to return from the exiles in places like Paris and Mexico.65 On September 15, Guatemala’s Independence Day, columns of machete-wielding campesinos paraded through the city center, proclaiming their loyalty to Ponce. The press speculated that the president had bribed the poor rural citizens in an attempt to aggravate urban ladino fears of the rural indigenous masses.66 The suspicious assassination of the founder of the popular opposition newspaper El Imparcial (founded in 1922 by members of the celebrated Generation of 1920) also seemed linked to Ponce’s attempt to maintain control. Citizens doubted whether the December elections would take place and if so, that they would be fair. Some students, teachers, and other citizens began to collect weapons for an armed insurrection.

A clearer plan had developed within the armed forces. At around 2:00 A.M. on October 20, young officers in the prestigious National Guard seized the Matamoros Barracks and laid siege to San José Castle, the Army’s most important storehouse for powder, munitions, and arms at the southern edge of Guatemala City. The young National Guard officers resented the cronyism that had limited high-ranking positions to loyal officers from elite families and the mistreatment that had characterized their years of service.67 They distributed arms to between two and three thousand troops and civilians, including some students and alumni, like José Rölz-Bennett and the Méndez Montenegro brothers.68

This chapter began with a scene from the following morning, when National Guard tanks rolled toward the National Palace and Ponce and Ubico were perhaps in hiding or had fled the country. Two military men, Jacobo Arbenz and Francisco Javier Arana, and one civilian, National University alumnus Jorge Toriello, assumed executive power. A grand celebration of the revolution was delayed until October 26, when about 100,000 civilians marched through the city center. Students joined campesinos, workers, teachers, and the poor below the balcony of the grand Post Office to greet the new ruling junta. The junta suspended the Constitution, dissolved the Legislative Assembly, and expelled a handful of generals and police chiefs. Ubico’s capricious rule was over. Just two years had passed since the escuilaches had dreamed of “teachers, ideologues, leaders” who would speak “to them of the destiny of the nation with a true heart.” Maybe Arbenz, Arana, and Toriello could be just such a trio.

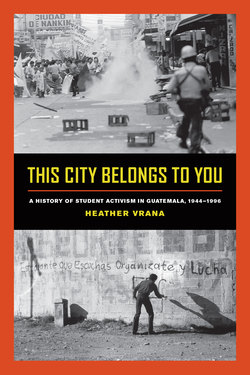

FIGURE 1. Citizens gathered in front of the National Palace, October 20, 1944. Photograph by J. Francisco Muñoz. Enrique Muñoz Meany Collection, Fototeca Guatemala, Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA).

MAKING A REPUBLIC FROM THE UNIVERSITY

For their role in the revolution and elite academic preparation, many student leaders were rewarded with high-level appointments or elected positions in the new revolutionary government. Recent graduates of the university’s Law Faculty became architects of the nation-state as ministers in the executive branch, representatives in the Legislative Assembly, and delegates in the Constitutional Assembly. Two years after dreaming up their ten-year plan to create revolution, Galich and the gadfly escuilaches began to rebuild the government from the very seats of power they had opposed. This made for a very young government. Alfonso Bauer Paíz, who served as Minister of Economy and Labor, was 26 years old. Galich, the recently elected president of the Legislature, was an elder among the students at 31 in 1944. The average age of a member of Congress by 1951 was 35, but some congressmen were as young as 22. These student-statesmen balanced homework with the legislative agenda, running from Assembly to class on any given day.69

Fittingly, education was one of the first issues confronted by the new government. Two weeks after Ponce’s defeat, the junta presented Decree 12 to the Congressional Education Commission (CEC). In addition to honoring students for their bravery in the revolution, the decree acknowledged how the university had suffered during the dictatorship. Under Ubico, the decree read, the university was made into a “factory of professionals where investigation was hollow and thinking lost all relevance.”70 A gesture of good will, Decree 12 granted the university autonomy in “intellectual, cultural, and administrative questions.” But to the CEC’s student-statesmen, it was useless to grant autonomy to the existing institution, formed as it was during the “asphyxiating” dictatorship.71 They rejected even the implicit limitation of the university’s autonomy to “intellectual, cultural, and administrative questions.” For the junta, Decree 12 was a symbolic recognition while the CEC balked at abstractions that might be empty in practice. The junta suggested reform while student–statesmen demanded total regeneration. The CEC reasoned that a new nation needed a new university.

The CEC made significant changes to the junta’s decree. They began with the university’s name. The National University would again be called the University of San Carlos (USAC), a gesture to its prestige in the colonial era. Next, the CEC pledged to extend the university’s reach beyond the capital city through extension programs and branch campuses. Additionally, they reserved the right for the university alone to alter, form, or dissolve any programs of study in accordance with society’s changing needs. Most importantly, the CEC limited executive power over the university by eliminating an article in the initial draft of the decree that permitted the executive to intervene in the university in certain circumstances. Individuals chosen by the USAC electorate were solely responsible for its operation. National well-being and scientific, technological, and cultural development would be in the hands of the autonomous university.

The CEC also formed two new programs in Mathematics and Humanities, which demonstrated the university’s new attitude toward knowledge production.72 Instead of engineering, an applied science that created technicians, the new USAC emphasized theoretical mathematics. In turn, the Humanities facultad would serve as the university’s ethical compass.73 As the keynote speaker at its inauguration, President Arévalo declared, “Our university is indebted to the youth of Guatemala,” but “mediocrity, sensationalism, and mercantilism . . . have impoverished us and we are going mad.” He continued, “We need teachers for the youth: we need something like priests, charged with telling us in which direction the nation ought to go.” The Humanities program was designed to produce just these types of thinkers who would through their word and their conduct inspire “faith, courage, and self-sacrifice” in the youth.74 Arévalo called on students to lead the people of Guatemala as secular priests.

In these first months of the Revolution, students, faculty, and alumni worked to restructure both the university and the nation in the image of an ideal republic. Their efforts not only revised the laws that governed the university, but also confirmed the presence of a coherent civic block at USAC. The ruling junta, CEC, and daily newspapers consistently referred to students, professors, and administrators as “San Carlistas.”

San Carlistas also joined the Constitutional Assembly, which hurried to write a Constitution before Arévalo’s inauguration on March 15. The Constitutional Assembly united two generations of San Carlistas: elders of the Generation of 1920, who as members of the Unionist Party had aided the overthrow of Estrada Cabrera, and neophytes who had entered national-level politics with the Revolution. The elders included luminaries David Vela, Francisco Villagrán de Leon, José Rölz-Bennett, Clemente Marroquín Rojas, and José Falla. Some escuilaches were among the younger generation. Of the Commission of Fifteen that initially drafted the Constitution, fourteen members were lawyers or law students; one was a medical doctor.75 Unsurprisingly, their chief concerns were universal suffrage, literacy, and federal social reforms, including university extension programs, and the foundation of the National Indigenista Institute (IIN), which sought—in certain terms—to improve government relations with rural indigenous citizens.76

While student-statesmen discussed these concerns within the immediate context of Guatemala, they also engaged with larger ideological debates that circulated throughout much of the world after World War II. The Constitutional Assembly employed the new human rights–based language of organizations like the United Nations. San Carlistas were also early members of the International Union of Students (IUS) in 1946, an organization with consultative status in the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).77 Contemporary internationalist ideals were reflected in the Assembly’s invocation of the “democratic spirit” that divided the world into two antagonistic blocs: fascist and democratic. In Guatemala, however, this sweeping call for democracy elided liberal and popular political concerns. This elision enabled a strong governing coalition, albeit one with deep internal divisions.78 Within a decade, conflicts over the precise meanings and practices of democracy would destabilize the revolutionary governments, a topic taken up at length in Chapter 2.

But even in the Revolution’s first months, the tension between liberal political philosophy and popular concerns put intellectual elites at odds with urban workers, rural farmers, and the jobless. Some of these divisions were exposed in the debate over universal suffrage. The ruling junta opposed extending the right to vote to illiterate men and women because they were seen as remnants of feudalism, not modern citizens, and therefore ineligible for the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. The junta insisted that restricting the vote to literate citizens would secure the nation for democracy and protect it against fascism because illiterate people were likely to be exploited by politicians, an argument supported by the historical memory of the presidency of Rafael Carrera and other nineteenth-century caudillos. Initially, the AEU and the AED agreed. Contradictory as this may seem, it serves as a reminder that San Carlistas were literate, ladino, mostly urban—in a word, urbane.

The junta, student leaders, ministers, advisors, and members of the Assembly came from the only ethnic, class, and regional background where the ability to read and write in Castilian Spanish was common. In 1950 (the first post-revolutionary census), 73.8 percent of Guatemala City residents were literate, while national figures including the majority-indigenous periphery recorded only 27.8 percent literacy. Many urban intellectuals accepted this evidence of the link between indigeneity and illiteracy. In summary comments in the national census, unnamed statisticians reiterated the implications of these numbers: “Literacy, taken to mean the ability to read and write, has always been considered one of the best means to judge the cultural level of a population . . . while nearly a half of the ladino population (49.1%) is literate, only 10 percent (9.7%) of the indigenous population is [literate].”79 The elite status of professionals is even clearer in terms of national employment statistics. In 1940, Guatemala’s economically active population counted 1,846,977 individuals; of this group of nearly 2 million workers, only 2,145 worked in what were called the “liberal professions” (profesiones liberales) as lawyers, notaries, doctors, surgeons, dental surgeons, pharmacists, midwives, and topographical and civil engineers. That is, less than 0.12 percent of economically active Guatemalans had careers in professional fields. By contrast, 45.8 percent (846,103) of economically active individuals did domestic service work and 42.1 percent (777,509) did agricultural work. Together this nearly 88 percent of the population performed labor that did not require schooling or literacy.80

Moreover, professionals were concentrated in the capital city. In 1940, more than half of Guatemala’s 413 lawyers lived in the capital. A decade later, around 62 percent of Guatemala’s lawyers, doctors, surgeons, dental surgeons, and topographical and civil engineers lived in the Department of Guatemala, where Guatemala City is located. The remaining 38 percent were scattered unevenly throughout the other twenty-one departments. When the 1950 census noted an illiteracy rate (72.2%) that exceeded the recorded indigenous population (53.5%) by nearly 20 percentage points, these data were taken to indicate that there was also a “regular quantity of illiterate ladinos,” which led some social scientists to understand rurality as a factor in illiteracy. The same census recorded that only 22 percent of individuals over the age of seven in Guatemala City had attended “any school or classes whatsoever.” Plainly, to attend university was extremely rare, and to graduate was even rarer. Most San Carlistas had attended the same preparatory schools and known one another for decades by the time they reached university. Professionals and students formed a small, tight-knit, mostly urban, ladino community.81

All of these factors—race, region, and fraternity—weighed heavily on the Constitutional Assembly’s discussion of granting full suffrage to illiterate Guatemalans.82 USAC alumnus and conservative editor of the newspaper La Hora Clemente Marroquín Rojas observed that the debate divided civil society into two sectors: on one side “industrial workers, laborers, and some youths and students,” and the other “pure gentlemen: many students, but all ‘respectable people [gente decente].’”83 North American anthropologist Richard N. Adams looked on and dismissed the revolutionary yearnings of the escuilaches because of their apparent hypocrisy. He wrote, “the Faculty of Law, the locus of such radical student protests, [produced] a population of professionals that is apparently incapable of altering the system and is, instead, deeply involved in its continuity.”84 Adams’s observation certainly echoed the contemporary belief that the middle class ought to exemplify the “ideal of private prosperity and public virtue thought to be crucial to the smooth functioning of modern societies.”85 Actually, as I mentioned above, there was tremendous ideological difference among the escuilaches. Nevertheless, while the ruling junta, the AEU, the AED, and some members of the public opposed the vote for illiterate citizens, the majority of the Constitutional Assembly, many political parties (including president-elect Arévalo’s PAR), and most of the general public favored at least an open ballot for illiterate citizens.

Before long, the AEU changed its position. In their statement about the shift, the AEU leadership declared with confidence that it could not “stand against the interests and ideals of the pueblo.”86 In order to achieve political and social equality, the nation needed all of its citizens to participate. Further, they wrote, the restriction of illiterate citizens’ right to vote “forecloses and annuls the human character of our laborers, most of all of our industrial workers who have given sufficient proof of their patriotism and civility.”87 Still, they favored an open ballot for a short period while illiterate citizens were taught civic literacy, reading, and writing. As the foremost student group, the AEU represented San Carlistas as custodians of the knowledge and skills that were prerequisites to the franchise.

Not everyone was so easily persuaded. One important event must have loomed large in the newspaper debates over universal suffrage: the violent conflict between ladinos and Kaqchikels in Patzicía on October 22, 1944. Capital city newspapers described the aggression of the Kaqchikels and used the events to demonstrate how rural indigenous Guatemalans were unprepared for full citizenship.88 They did not report the fatal mismatch of machetes versus guns that placed indigenous combatants at a deadly disadvantage. Flashpoints such as these provided opportunities for middle-class professionals and students to demonstrate their own cultural and political difference, to celebrate their urbanity, and articulate a “dialectical brew of optimism, anxiety, and contradiction” that promoted certain manners as requisite for citizenship.89

In El Imparcial, just a few months later, illustrious journalist Rufino Guerra Cortave echoed this view when he wrote, “the rural man, the illiterate, the laborer, Indian or ladino, continues in his ignorance and, consequently, continues to be a danger, to be manipulated by the perverse maneuvering of the enemy.”90 For Cortave, the indigenous citizen was not to be faulted for his ignorance, but rather “four centuries of oppression, cruelty, and systematic brutalization of the native” had “made him so indolent and apathetic,” and “resigned to his lot.”91 Ongoing oppression rendered the indigenous community (and illiterate ladinos) incapable of participating in the social contract. Cortave continued, “To beings whose lack of consciousness is a cloud in our sky of democratic liberties . . . we must take reason . . . we must infuse the ABC of civilization.” After all, if one had not learned more than the most rudimentary reading, he “is not guilty if he cannot discern good from evil and it is the duty of the rest of the Guatemalans of conscience to show them the path of their own best interest if they are to be part of this society.” This task could be achieved “with reason and patriotic honesty as guides.”92 Cortave’s quasi-expert discourse declared that only with literacy could one have reason, discern good from evil, and be counted upon to act in their own best interest. The process of coming to consciousness by those blameless for their lack of it required a certain submission to a course of treatment by the more wise.

In La Hora, Jorge Schlesinger argued that the “Indian” was an “irresponsible subject” because of “his lack of education and inadaptability.” Like Cortave, he encouraged the incorporation of the indigenous as citizens in the national community. But for Schlesinger, inclusion was owed because “he is the pillar of the national economy which is based mainly on agriculture” not because inclusion was “necessary to unify the national conscience,” as Cortave had written.93 In fact, the government was duty-bound to look after the indigenous, if only so “that he may be useful to the fatherland.”94 Cortave, Schlesinger, and the AEU agreed on the conclusion if not on the rationale: illiterate rural indigenous laborers and their ladino counterparts must be enfranchised.

Suffrage became “obligatory and secret” for literate men; “optional and secret” for literate women; and “optional and public” for illiterate men. Illiterate women were not mentioned at all in the Constitution.95 A woman thusly located in the assemblymen’s understanding of political authority could not possibly properly exercise citizenship. The question was settled in the Constitutional Assembly, but it revealed a rift that was not easily mended. Civil society was the precondition of democracy, but education was the precondition of civil society. San Carlistas were charged to infuse the “ABCs of civilization,” and in so doing enact the most enduring feature of the new student nationalism: the responsibility of the students to lead the nation.

The new constitution was completed in time for Arévalo’s inauguration. On March 15, 1945, President Arévalo stood before a crowd in the congressional chambers. He declared, “We are going to equip humanity with humanity. We are going to rid ourselves of guilt-ridden fear through unselfish ideas. We are going to add justice and happiness to order, because order does not serve us if it is based on injustice and humiliation.” He continued, “We are going to revalorize, civically and legally, all of the men of the Republic . . . Democracy means just order, constructive peace, internal discipline, [and] happy and productive work . . . a democratic government supposes and demands the dignity of everyone.”96 Dictatorship, or order “based on injustice and humiliation,” was abolished. Yet real democracy required “internal discipline, happy and productive work,” and men who had been “revalorized.” Later in the address Arévalo confirmed, “we are [working] directly for a transformation of the spiritual, cultural, and economic life of the republic.” The speech was a vow to teach civic values to all citizens who had lost or not yet acquired them. Arévalo added that Guatemalan democracy would become “a permanent, dynamic system of projections into society [by] tireless vigilance.”97 Some of Arévalo’s populist contemporaries, like Victor Haya de la Torre in Peru and Juan Perón in Argentina, had made similar claims, occasionally inspiring the support and at other times the ire of the middle class.98

FIGURE 2. President Arévalo depicted as a woman before a stereotypical indigenous peasant on a float for the desfile bufo, 1945. Anonymous Photograph. Collection of Juan José Arévalo Bermejo. Fototeca Guatemala, Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica (CIRMA).

Once in office, Arévalo called on San Carlistas to design the tax reform and new social security program, and to lead teams of doctors, lawyers, and engineers into the countryside to organize free clinics. Arévalo and his advisors also promoted national culture through fiction, poetry, music composition, and fine art contests.99 His democratic vision fused Rooseveltian social liberalism with Lockeian liberalism, the legacy of late nineteenth-century Central American Liberalism, and the populist political style that was en vogue across Latin America.100 His populism empowered intellectuals, experts, and policymakers through interwoven projects of economic development, human welfare, and political tutelage. Before long, advisors and funders from the United States would utilize these networks to implement a kind of soft imperialism in the context of the Cold War.101

The Arévalo government designed comprehensive reforms for every level of the educational system. The reforms ushered in a new period of openness. Professors and students returned from exile and brought with them experiences gained in Mexico and further afield.102 Schoolteachers were encouraged to restructure professional credentialing and rethink their teaching methods. Hundreds of new primary and secondary schools were built with government subsidies. The new Instituto Normal Nocturno, a night school, enabled workers to have access to the nationalist positivist curriculum of the highly regarded “cultura normalista.”103 At USAC, administrative reform crafted a republican government for the university: a legislature, the University High Council (CSU); an electoral college, the University Electoral Body; and an executive, the rector. The rector presided over the CSU, but its membership included the deans of all academic units, a professional delegate from every colegio, and a student delegate from each academic unit.104 Elections by secret ballot in the University Electoral Body replaced the personal appointment of the rector. Colegios, like guilds, regulated professionals’ training, examinations, and licensure; they served as a political bloc and social organization for members. The inclusion of colegios in university governance meant that although San Carlistas changed phases, from student to professional, and frequently, from professional to professor, their obligation to USAC endured.105

Education reforms progressed quickly, but Arévalo had more difficulty launching reforms in other areas. His economic policy based on a system of capitalist growth through agricultural export of coffee, cotton, and petroleum and moderate labor and finance reforms suggests he was cautious about impacting export production. The 1947 Labor Code restored the right to unionize to urban unions, but placed limitations on agricultural unions.106 Two of Arévalo’s most lasting reforms were the formation of the National Institute for the Promotion of Production (INFOP) and the Guatemalan Social Security Institute (IGSS) in 1948. These institutes sought to expand and diversify industry and agriculture, and focused on industrialization, credit, home construction, the indigenous economy, and cooperatives.107 San Carlistas advised both institutes.

But Arévalo was an educator, and not an economist or agronomist.108 His uneven policies and their consequences fueled debate over the meaning of the revolution. Historian Piero Gleijeses has argued that Arévalo’s economic reforms failed because they did not transform Guatemalan economic structure; the reforms actually reinforced the inequalities that his educational and cultural programming attempted to mitigate.109 For his part, Arévalo himself wrote in 1939 that any education reform would fail in Guatemala without structural reform.110 Nevertheless, as president, he pursued precisely the opposite policy. School attendance removed children from the household where they could have learned useful skills and contributed to the family’s economic activities. Making matters worse, the government could only afford to send empíricos to rural schools. Empíricos were a category of teacher who lacked regular credentials. They had not attended a Normal School and were scarcely more educated than their pupils. Worse, they were usually ladino and tackled a difficult job for which they were unprepared: teaching indigenous rural students with scant support and supplies.111

Yet the authors of these new plans and programs lived in the capital city where only 7.8 percent of the population was indigenous in 1950. The indigenous citizen-to-be was a stranger, someone known through literature and legend. Despite victorious assertions of national unity that affirmed indigenous Guatemalans’ full citizenship in the revolutionary government, chauvinism and misunderstanding endured. Take the words of Antonio Goubaud Carrera, an USAC professor of anthropology and the first director of the IIN: “Indigenismo, a word that seems as if it were of recent use, meant ‘the protection of the indigenous’ at the beginning of the colonial period . . . [Now] indigenismo denotes a consciousness of social problems that ethnic aspects of indigeneity present, relative to western civilization . . . the manifestation, the symptom, of a particular social unease.” The gravest problem was how indigenous people lacked a national perspective, and spoke “strange languages,” wore “fantastical costumes that set them apart from the rest of the population,” were “tormented by beliefs that a simple drawing would eliminate” and “bound by technologies that date to thousands of years before.”112 The IIN’s objectives were research and data collection. Its experts began by defining who was “an Indian.”113 Writer and San Carlista Luis Cardoza y Aragón observed in 1945, “The nation is Indian. This is the truth that first manifests itself with its enormous, subjugating, presence.” “Yet we know,” he continued, “that in Guatemala, as in the rest of America, it is the mestizo who possesses leadership throughout society. The mestizo: the middle class. The revolution of Guatemala is a revolution of the middle class . . . What an inferiority complex the Guatemalan suffers for his indian [sic] blood, for the indigenous character of his nation!”114 In other words, to deliver the middle class—here a synonym for mestizo or ladino—revolution, urban professionals had to venture into the countryside to study the exalted past and teach the retrograde.

There was no bigger advocate of this type of university extension than President Arévalo’s good friend, respected surgeon Dr. Carlos Martínez Durán. In August 1945, Martínez Durán was elected as the first rector of the autonomous university. He was a great admirer of John Locke, Max Scheler, Miguel de Unamuno, and José Martí, and when he could, he implemented their ideals at USAC. At his inauguration, he proudly proclaimed, “The student is the pueblo in the classroom!”115 He famously said, “Universitario, this city belongs to you. Construct within her your talent, so that future generations can quench their thirst for knowledge here. May your academic life be sacred, fecund, and beautiful. Enter not into this city of the spirit without a well-proven love of truth.”116 Thus charged, AEU students went out into their city with their “sacred, fecund, and beautiful” intellects. Although these efforts were complex and mediated by regional and ethnic prejudices, to say nothing of students’ inflated sense of duty, the university’s gaze outward toward the pueblo outlasted the Ten Years’ Spring. It became a treasured aspect of San Carlista student nationalism, sometimes referred to as “nation building” or “hacer patria.”

Building the nation was, curiously, the theme of an homage to Francisca Fernández Hall, USAC’s first female civil engineer, celebrated in July 1947. The event began with a speech from president of the Engineering Students’ Union (AEI) Héctor David Torres about the role of women in Guatemalan society. He spoke, “women also build the nation, because hacer patria does not only mean to defend the nation on the field of battle, nor to attain the highest governmental appointments. Hacer patria is to educate the people . . . to acculturate oneself . . . to work loyally and honestly.” Torres acknowledged that women did not currently have a place in national-level leadership, but “if they were capable of facing domestic life as a mother, wife, or sister, then they were capable of successfully confronting the intricate problems of science.” Importantly, only two women were mentioned in the newspaper’s reportage of the event: the woman elected beauty queen of the Engineering facultad and Fernández Hall herself. While the university’s official Boletín Universitario detailed speeches delivered by men in honor of her, of Fernández Hall it reported only that she “expressed her gratitude” on behalf of all Guatemalan women.117 Women remained marginal to the rising chorus of San Carlistas student nationalism, invoked as figures or objects who helped reinforce gendered understandings of valor and responsibility and, ultimately, political authority.

In the same issue of the Boletín Universitario, editors reminded their large readership that university extension was an integral part of national social reform.118 They promoted the Faculty of Humanities’ weekly radio show on TGW, which offered programs on topics as varied as government policy (income tax and agrarian reform), social concerns (consumerism, Guatemala’s leading cause of death, and alcoholism), political rights (rights and responsibilities of the press and the Declaration of the Rights of Man in Guatemalan jurisprudence), and narrower topics like citizens’ satisfaction with USAC and listeners’ favorite Guatemalan writers. One program asked listeners whether they considered Guatemala one unified or many individual nations. Another contemplated the claim that man cannot live without philosophy.119 The program projected the university as far into the pueblo as the Spanish language and radio signal could reach.

At this time, USAC also became involved in transnational academic exchanges. Free from Ubico’s restrictions, the university soon relaunched its lively foreign exchange program and hosted scholars from across the Americas and Europe.120 In 1950, USAC participated in the World Conference of Universities in Nice, France. The following year, AEU students attended the International Conference of Students in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), where they met other students from around the world, including Liberia, Cuba, Morocco, Algeria, French West Africa, British East Africa, and England. It is not clear what came out of these travels. Certainly students had adventures and gained new pen pals and a sense of a global student experience. They also began to read a popular international student newspaper entitled The Student (not to be confused with the USAC newspaper of the same title). Notably, through the 1950s, San Carlistas traveled to socialist bloc countries, Western democracies, and colonial African nations. Certainly these travels expanded San Carlistas’ perception of the world, especially regarding the effects of U.S. and European imperialism. The imprint of these connections is evident in some anticolonial writings by San Carlistas, addressed in later chapters.

Martínez Durán also traveled widely. Surprisingly, since the Arévalo and Arbenz governments would soon become their sworn enemies, the U.S. State Department and UFCO hosted Martínez Durán for six weeks in 1948. After the visit, Martínez Durán published a multi-part essay about his travels in the Boletin Unversitario. The entourage toured Tulane University, the University of North Carolina, Duke University, American University, and Georgetown. According to the rector, they avoided political discussions. For Martínez Durán, the tour underscored two crucial differences between Guatemala and the United States: the large indigenous population and rural poverty. Upon his return, he reiterated the importance of national pride and asked San Carlistas to pay special attention to these unique problems. He planned to offer extension programs in the sciences, technology, philosophy, and art to elevate all Guatemalans. He lamented secondary schools students’ poor preparation in the humanities as compared to the United States.121

Martínez Durán also emphasized the proper physical environment for learning. In an essay written for the Boletín Universitario, he imagined a University City where “the finest of honeys will be distilled from the nectar of the youth . . . where life finds fulfillment, and the universal and the national, in a close embrace, will decide the destiny of Guatemala.”122 He envisioned faculty and students living together in a model city where they would be inspired by nearby mountain ranges and could forge new knowledge through neighborliness and sports rivalries.123 In fact, the construction of a model University City was a regular theme in the Boletín Universitario for much of the mid-1940s, as USAC and other Latin American universities began to plan new campuses to promote students’ mental and emotional development.124 The first modest step, a residence hall, was completed in February 1951. According to a special feature story in the Boletín Universitario, the residence hall was intended to eliminate the “great enemies of San Carlistas”: “malnourishment, dangerous living, and isolation.”125 Residents were treated to films, a lecture series, Saturday luncheons with prominent scholars, and a music library filled with Wagner and Chopin records. The residence hall also fostered USAC’s first athletic teams. As advocates of “a sound mind in a healthy body,” Congress heartily approved.126

The new Republic of Guatemala and USAC came of age together. From exile years later, Arévalo referred to these years as a period of “creole nationalist revolution,” invoking nineteenth-century revolutions for independence from Spain and underscoring the revolution’s racial character. Martínez Durán’s plans for the university complemented Arévalo’s efforts to make Guatemala a more fecund environment for the development of national culture.

A REPUBLIC OF SAN CARLISTAS

President Arévalo and Rector Martínez Durán envisioned reciprocal paths toward progress for the nation and the university. A close friendship paralleled their shared professional goals. But their terms ended in 1950, Arévalo’s with the election of Colonel Jacobo Arbenz, and Martínez Durán’s with the election of engineer Dr. Miguel Asturias Quiñonez.127 From this moment, the paths of USAC and the Republic of Guatemala diverged. Asturias Quiñonez represented the many conservatives who were not enthusiastic about the Revolution’s reforms and had continued to exercise influence through daily newspapers, businesses interests, and the Catholic Church during Arévalo’s presidency. Arévalo had prioritized the university, but Arbenz focused elsewhere. Arbenz was a military man, not an educator. Arbenz was inspired by friendships with young Guatemalan communists, including escuilach Fortuny (who served as his speechwriter), Alfredo Guerra Borges, Victor Manuel Gutiérrez, Enrique Muñoz Meany, and Augusto Charnaud MacDonald. With them Arbenz read Marx, Lenin, and Stalin; national history; and agronomy in order to understand Guatemala’s colonial past and structural inequality.128 Some of these young men were San Carlistas, but their focus was on land reform and labor, not education.

The new president’s study of agricultural history and contemporary agronomy helped him to draft a dramatic agrarian reform and significant public works projects. His agrarian reform expropriated and nationalized idle lands so that campesinos could plant and harvest food for sustenance. In turn, his public works projects focused on three large infrastructural developments: a major highway from the capital to Puerto Barrios to rival the North American–owned IRCA train line; the construction of a second port to solve the transport bottleneck caused by inadequate facilities at Puerto Barrios; and the construction of a hydroelectric plant to supplement the expensive and inadequate service provided by the U.S.-owned monopoly Empresa Eléctrica.129 Arbenz’s immediate aim was to promote industrialization while continuing to provide much-needed jobs for Guatemalans in agricultural and manufacturing sectors. He sought to connect Guatemalans to the world through investment in domestic communication and transportation networks. This was also practical, as the United States and the World Bank declined to invest in Guatemala’s structural development after hearing of Arbenz’s ties to communists. Taken together, the agrarian reform and public works projects undermined the longstanding economic power of North American businesses.