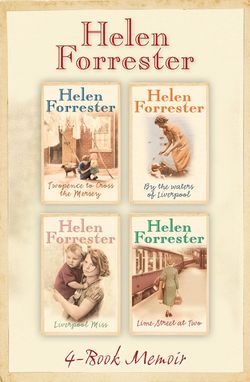

Читать книгу The Complete Helen Forrester 4-Book Memoir: Twopence to Cross the Mersey, Liverpool Miss, By the Waters of Liverpool, Lime Street at Two - Helen Forrester - Страница 20

CHAPTER TWELVE

ОглавлениеOne of the advantages of being very poor is that one has time. Since we had no clothes except those on our backs, there was no pile of washing to be dealt with each Monday. When there is little food, there is little cooking, and since we possessed no bed linen, towels, cleaning materials or tools, most other domestic jobs either were non-existent or could not be carried out. As the weather improved, therefore, I began to take a walk each day, pushing Edward and Avril in the Chariot.

These were, for me, voyages of discovery into a world I had never dreamed of before. I meandered along narrow streets, where the soot-blackened early Victorian houses opened directly upon the pavement. Some of the houses had the flagstone across their front door scrubbed and neatly whitened, with a strip of well-shone brass covering the sill; their painted window-sills were carefully polished and their garish chintz curtains were starched as stiff as the sentries outside Buckingham Palace. Others were like our house: dull windows veiled in grey webs of lace, window-panes missing and filled in with cardboard, old orange-peel and cigarette-ends littering their frontage.

The local pawnbroker’s shop, with its dusty sign of three golden balls hanging outside over a wooden table piled high with second-hand clothing, made for me a fascinating treat. I loved to gaze in the windows at the rows of Victorian and Edwardian rings for sale, the war medals, violins, blankets, china ornaments and sailors’ lucky gold charms.

The pawnbroker himself was part of the scene, as he stood in his doorway puffing at a cigarette, shirt-sleeves rolled up to show olive-coloured arms, tight black curls receding from his forehead, a magnificent watch-chain with dangling seals swathed across a wrinkled, blue serge waistcoat over a comfortable paunch.

‘Come on, me little blue-eyed duck!’ he would call to Avril when he saw her, and occasionally he would feel around in his waistcoat pocket with his tobacco-stained fingers to dig out a grubby sweet for her. She loved him and would howl dismally on the days when we did not walk that way. For me, he would have a polite nod and a brief Afternoon. Nice day’, regardless of whether it rained or shone.

One mild March afternoon, I circled the cathedral and listened to the ring of the stonemasons’ tools on its great sandstone walls. It rose like a graceful queen above slums which put Christianity to shame. I stared up the beautiful sweep of steps leading to its entrance, wondering if I dare go in, but I was too afraid. I had not seen myself in a mirror since coming to Liverpool, but I knew I was both dirty and shabby. My hat and shoes had been passed to Fiona, who was obliged to go out to school, whereas I could stay indoors. The shoes had been replaced by a pair of second-hand running shoes with holes in the toes; my head was bare and my hair straggled in an unruly mass down my neck; it was rarely combed and never washed.

Still pushing aimlessly, I wandered along Rodney Street, a lovely street of well-kept Georgian houses, the homes and surgeries of Liverpool’s more eminent doctors. A brass plaque on No. 62 informed me that Gladstone was born there. Mr Gladstone was not one of my heroes, so I continued onward enjoying the peace and orderliness of the quiet road.

I turned down Leece Street, past the employment exchange where Father spent so many unhappy hours, past tall, black St Luke’s Church and into Bold Street, the most elegant shopping centre in Liverpool. Although there were at least a dozen empty shops up for rent, the atmosphere was one of opulence. I pushed past women in fur coats and pretty hats, who stared at me in disgust, to look in windows which held a single dress or fur or a few discreet bottles of perfume. A delicious odour of roasting coffee permeated the place.

Onward I went, through the packed shopping area of Church Street, where trams, nose to tail, clanged their way amid horsedrawn drays, delivery vans and private cars, and newspaper men shouted to me to ‘read all abaat it’. The cry of ‘Echo, Echo, Liverpool Echo, sir’ comes wafting down the years, like the overwhelming scent of vanilla pods, the sound and smell of a great port.

‘I know where we’ll go,’ I said to Avril, who was bouncing up and down in the Chariot pretending it was a horse.

‘Where?’

‘We’ll go down to the Pier Head!’

I knew this part of the town, because I had been shopping in it on many occasions with my grandmother. I pushed the Chariot purposefully up Lord Street to the top of the hill, where Queen Victoria in pigeon-dropped grey stone presided, down the hill, through a district of shipping offices with noble names upon their doors: Cunard, White Star, Union Castle, Pacific & Orient, the fine strands which tied Liverpool to the whole world. Past the end of the Goree Piazzas, an arcade of tiny shops and offices, where out-of-work sailors lounged and spat tobacco and called hopefully after me, under the overhead railway which served to take the dockers to work, and a last wild run across the Pier Head, dodging trams and taxis, to the entrance to the floating dock.

At last I had found it!

The river scintillated in the sunshine; a row of ships was coming in on the tide; a ferry-boat and a pilot-boat tethered to the landing-stage rocked rhythmically; screeching gulls circled overhead and swooped occasionally to snatch food from the river. A cold wind from the sea tore at my cardigan, jostling and buffeting my skinny frame. I put the hood of the Chariot up to shield Avril and Edward from it.

The shore hands were casting off the ferry-boat, and I looked wistfully out across the water at the empty Cammell Laird shipyards in Birkenhead. My eyes followed the shore along to the spires of Wallasey, and mentally I followed the railway with all its dear familiar station names along the coast to West Kirby. On that railway-line lived Grandma, who was so angry with Father that she never wrote to us. There was a middle-class world, where people could still wash every day in clean bathrooms. The slump had reached some of them, I guessed; but once past Birkenhead, I thought sadly, it could not be half as miserable as Liverpool was. Perhaps, if I could see Grandma and describe to her my mother’s terrible suffering and my father’s despair, she would forgive them and help them.

I longed to push the Chariot up the ramp of the ferry-boat and escape, run away from our smelly rooms, from hunger and cold, the cold which was raking through me mercilessly now, and from people who looked like the gargoyles on the old cathedrals I had attended in the past.

‘The ferry costs twopence,’ I reminded myself, as I wrapped Avril and Edward closer in their inadequate piece of blanket, ‘and you haven’t got twopence.’ Furthermore, Grandma, though long since widowed, had been married to a businessman who never failed, and who had come from a long line of ironmasters and merchants who always seemed to have done very well for themselves – she just would not understand.

The way home seemed incredibly long, and I paused at the bottom of Bold Street, to stand for a moment in the warmth of a shop doorway before continuing. A shopwalker behind the glass door frowned at me as I hauled the Chariot close in. The shoppers were thinning out rapidly and I watched them hurrying to their cars, parked at the kerb, or into Central Station. And there she was!

Joan! My own best friend!

She was sauntering down the pavement in her neat school uniform, her mother beside her, presumably here on one of her visits to her grandmother. I had not seen her since leaving my old home and, presumably, she knew nothing of my recent adventures – one day I had attended school with her; the next day I had been whisked away to Liverpool.

I started forward.

‘Joan!’ I cried, my heart so full of gladness I thought that I would burst with sheer joy. ‘Oh, Joan!’

The mother stopped, as did Joan. The smiles which had begun to curve on their lips died half born. Without a word, they both wheeled towards the road, crossed it and disappeared into Central Station.

I stared after them dumbly. They had recognized me. I knew they had. Then why had they not stopped and spoken to me?

A gentleman told me irritably to get out of the way and I became aware that the Chariot and I were blocking the pavement. Still dumbfounded, I turned the pram homeward and slowly pushed it up the hill, gazing vacantly before me.

Coming towards me, amid the well-dressed shoppers, was an apparition. A very thin thing draped in an indescribably dirty woollen garment which flapped hopelessly, hair which hung in rat’s tails over a wraithlike grey face, thin legs partially encased in black stockings torn at the knees and gaping at the thighs, flapping, broken canvas covering the feet. This thing was attached to another one which rolled drunkenly along on four bent wheels; it had a torn hood through which metal ribs poked rakishly.

I slowed down nervously, and then stared with dawning horror.

I was looking at myself in a dress-shop window.

It was a moment of terrifying revelation and I started to run away from myself, pushing the pram recklessly through groups of irate pedestrians, nearly running down a neatly gaitered bishop. Every instinct demanded that I run away and hide, and for a few minutes my feet were winged. Halfway up the hill, back in the shadow of St Luke’s, however, under-nourishment had its say, and I sank exhausted on the church steps, while Avril giggled contentedly in the pram after her rapid transit up the street

I was disgusted with myself. I felt I could have done more. I was old enough to know that I should wash myself; at least cold water was available. And if I could wash garments through for the children, I could have put some of my own through the same water. I realized, with some astonishment, that I had always been told what to do. The lives of all the children had until recently been strictly regulated by a whole heirachy of domestics, some of them very heavy-handed, and a father who had, at times, used a cane with sharp effect. I washed when told to wash, went to school when told to go, however irksome it seemed, got out my playthings when permission was given. Disobedience was a crime and to query or object to adult orders, which were given without any supporting explanation or reason for them, was quite unthinkable. I don’t think that I had ever had an original thought until I had been plunged into this queer life in Liverpool, where I had been given the job of looking after my brothers and sisters.

Now, sitting on the blackened stone steps of the soaring Gothic church, I realized that neither Father nor Mother nor Grandmother nor servant was particularly interested in me. With all the bitterness and unreasonableness of a budding teenager, I saw myself as a convenient tool of my parents, my only reason for existence that I could take the care of the children off them.

I fastened the two remaining buttons of my cardigan, got up and wheeled the Chariot slowly up Upper Duke Street, skirting St James Cemetery with some trepidation in the gathering gloom. For the first time, I tried to think constructively, to devise ways in which the family might get out of the morass in which it was floundering; but my experience was too limited and my mind too dulled by lack of use, my body by lack of food, for me to be able to come up with a possible solution. Greater minds than mine were having trouble with the same problem. We were but one family amid millions of others.

I cried openly as I trudged along, my glasses sliding slowly down my nose, the tears making white rivers in my grey face.

When my parents came in that evening, I again brought up the question of my going to school. I was always very nervous when trying to communicate with them and probably I mentioned the subject too diffidently, because when I suggested that I would have to complete my education before I could hope to go to work in the future, Mother simply dismissed me by saying, ‘Don’t be absurd. Go and put Avril to bed.’ Father laughed and added, ‘I hope no daughter of mine will ever have to go to work.’

Father’s kindly meant remark startled me. Even a young girl like myself knew that times were changing and more and more women were entering the labour force. Lancashire had, in addition, a long tradition of women working, and the only future I could visualize as holding an iota of happiness for myself was one which contained a career.

‘But …’ I began.

‘That is enough, Helen. Do as you are told.’

And Helen, being a coward, did as she was told.