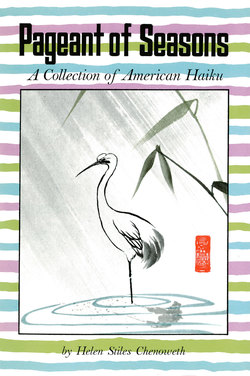

Читать книгу Pageant of Seasons - Helen Stiles Chenoweth - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

An interest in people and things Japanese has occupied three periods of my life that eventually led to the teaching of American haiku as part of work in creative writing classes.

When I was a child my mother read Japanese fairy tales and stories by Lafcadio Hearn to me. The story of kusahibari from his book Kotto was one of my precious memories of a "tiny insect whose particular kind of singing can be heard only in Japan." Years later I read his statement that poetry in Japan "is as universal as air. It is felt by everybody. It is read by everybody, composed by almost everybody, irrespective of class and condition."

This was a challenge to me when I first started to study the writing of poetry. One of the text books (now out of print) was used in experimental teaching of a second year high school class. First lessons were designed to write original poems in the haiku style and mood. In this experiment the pupils became haiku conscious of counting syllables as well as trying to emulate the exquisite work of the Japanese poetry in American fashion.

The result was that a term later the first class of its kind in the eastern part of the United States was open to students of third year English and to others as an elective. The study of poetry beginning with haiku was the second part of my interest in people and things Japanese.

The third period came when I had a class in Adult Education, teaching a group of women in the Los Altos Writers Roundtable in 1956. This was a workshop among women who wanted to write poetry, prose, and articles for publication. Prosody, the study of poetic meter and versification, proved to have its stumbling block among some of the writers who could neither apply nor relate syllables to their poetic efforts. Recalling a book I had used and its discussion of the use of haiku with syllabic content, was a directive toward promoting the study of Japanese haiku. I used haiku alone to relate the understanding and use of syllables, followed by the cinquain for meter identification in writing. The form cinquain was conceived by the poet Adelaide Crapsey who promoted its use as an American form after she had made a study of Japanese haiku.

A dozen determined women formed a special class of dedicated haiku writers. The result was Borrowed Water (Tuttle, 1966). During this time I wrote many haiku as suggestions for class work and examples of American mood, idiom, season, and other themes for writing haiku. Most of these were preserved for Pageant of Seasons, all written in California where the actual pageantry of seasons is brilliant, ever-changing, and associated with scenes that are as unpredictable as snow on a full-blooming rosebush in February.

I wish to thank the editors of American Haiku, Platteville, Wis., Haiku West, Forest Hills, N. Y., and Haiku Magazine, Toronto, Can., for their permission to publish haiku which appeared in their publications.

Los Altos, California

H. S. C.