Читать книгу Justice Miscarried - Helena Katz - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеRacism: The Donald Marshall Jr. Case

It was a Friday night on May 28, 1971, and seventeen-year-old Sandy Seale was playing pool with some friends in his family’s basement in Sydney, Nova Scotia. At 8:30 p.m., the athletic teenager grabbed his jacket, said goodbye to his parents, and headed off to a dance at St. Joseph’s Parish with a group of friends. But the dance was sold out by the time they arrived. After three unsuccessful attempts to sneak into the dance, Seale gave up. With his midnight curfew quickly approaching, he started walking toward Wentworth Park on his way to catch the bus home. When he reached the park, Seale ran into seventeen-year-old Donald Marshall Jr.

Junior, as family and friends called him, was from the Membertou Reserve. Following hearings in 1915, the Mi’kmaq band had been moved from highly-coveted land along the waterfront to a swampy site in a more isolated area. It took years for running water and electricity to be installed. A sewer system replaced outhouses only in the late 1950s.

The reserve of 125 band members was in the unusual position of being in an urban area, which made English the predominant language. But in the Marshall household, all the children spoke Mi’kmaq. Junior was the eldest of thirteen children. His father, Donald Sr., was the Grand Chief and spiritual leader of the 5,000 Mi’kmaqs who lived in the Maritimes. He also had his own plastering business. His mother, Caroline, worked as a cleaning lady at St. Rita Hospital in Sydney. The devoutly Catholic family was among the few on the reserve to have jobs; most people were unemployed and lived on welfare. Racism wasn’t unusual. Police sometimes warned white parents when their daughters were seen in the company of Aboriginal youths.

Junior had enjoyed attending school on the reserve, but got into trouble in a white school. He was expelled when he was fifteen after a teacher grabbed him by the ear and he hit her. He barely had a grade six education. He joined a group of toughs and had minor brushes with the law, including a four-month stint in the county jail for giving liquor to minors. Seale and Junior had met when Donald Marshall Sr. did some drywalling for Seale’s father. The two boys weren’t friends, but they ran into each other from time to time. At about 11:00 p.m. that spring evening they stopped to chat on the edge of Wentworth Park.

Just before midnight, Junior and Seale were seen talking to two men. One was a small, older man with grey hair. The other, Jimmy MacNeil, was younger and taller. The two men were on their way to the older man’s house after drinking seven beers each at the State Tavern, as well as some wine earlier in the evening. Roy Ebsary, the older man, was wearing a cloak and claimed that he was a priest from Manitoba. He asked if there were any women or bootleggers in the park. He invited the boys back to his house for a drink but they declined. They asked Ebsary for money. Seale was standing with his hands in his pockets. Suddenly, Ebsary pulled out a knife from beneath his cloak and plunged it into Seale’s stomach. The youth crumpled to the ground. Then Ebsary turned to Marshall and slashed him in the arm. Fearing for his life, Marshall ran. Ebsary and MacNeil fled to Ebsary’s house two blocks away.

Marshall ran into fifteen-year-old Maynard Chant, told him that a friend had been stabbed by one of two men, and showed him the cut on his arm. Chant, who had slipped out of a church service, was on probation for stealing milk money. He had been on his way home to Louisbourg when he bumped into Marshall. They flagged down a car and returned to the scene of the stabbing. Teenager Robert Scott MacKay, sixteen, and his date were walking to the bus stop when they found Seale on the ground. MacKay accompanied Marshall to a nearby house to call an ambulance. Chant took off his shirt and covered Seale’s wound. Then he headed home to Louisbourg.

When the police arrived, Constable Richard Walsh was the first on the scene. He found Seale lying in the street, moaning in pain, his intestines bulging from his abdomen. He was bleeding profusely: the knife had penetrated so deeply that it had sliced through his torso, cut his bowel and severed the aorta. The dying Seale was rushed to Sydney City Hospital as two police officers followed the ambulance. Oddly enough, no officers accompanied him in the ambulance, in case he was able to make a statement about the incident.

Marshall gave Corporal Howard Dean a description of the two men who had attacked him and Seale, but Dean didn’t write down the description in his notebook. Instead, the police officer placed Marshall in the back of the cruiser and brought him to the hospital to have his arm stitched up. Marshall also gave a description of the assailants to Sydney Police Sergeant-Detective Michael B. MacDonald. But he didn’t make a note of it either because his notebook was at the office. None of the police officers stayed behind to cordon off the crime scene to preserve evidence, search for a weapon, gather names of those at the scene, interview possible witnesses, or conduct door-to-door checks of nearby homes for a possible suspect or eyewitnesses. In 1971, the force’s officers didn’t have specialized training in forensic investigation of crime scenes. Instead, all four officers went to the hospital.

Seale received twenty-two pints of blood throughout the night, but his kidneys failed and he was placed on life support. Doctors operated twice, but at about 8:00 p.m. on May 29, 1971, less than twenty-four hours after being stabbed, Seale died without regaining consciousness. Although it was the hospital’s policy to notify the medical examiner when a patient died within twenty-four hours of surgery, surgeon Dr. Mahomad Naqvi, who operated on Seale, didn’t remember having done so. No autopsy was performed on Seale’s body to gather evidence for the police investigation.

It was Sydney’s first murder in five years, and the force’s police officers had little training in conducting investigations of this nature. Constable John Mullowney was dispatched to the park the morning after the stabbing to search for clues, but the crime scene hadn’t been secured nor photographed, and Mullowney didn’t have any training in handling evidence. He found a bloody Kleenex and turned it over to MacDonald without protecting it from contamination. Although the Sydney Police sometimes used the RCMP’s expertise with investigations, this time they rejected the help. They didn’t ask RCMP identification specialist John Ryan to photograph the park and the scene of the murder until more than two months later.

Sergeant of Detectives John MacIntyre took over the investigation the morning after the stabbing. Marshall spent much of that weekend at the police station in case officers had questions about the stabbing, but he wasn’t asked to give a formal statement until Sunday May 30, 1971. At 4:50 p.m., Marshall spoke to MacIntyre for twenty-two minutes during which he recounted meeting Seale in the park, then standing and talking on a footbridge for a few minutes before two men called them over to Crescent Street asking for cigarettes. The men said they were priests from Manitoba. Marshall said the older man was short, stocky, grey-haired, wore glasses, was dressed in a long blue coat, and was about fifty years old. He said he didn’t like “Indians” or “Negroes” when he stabbed Seale and slashed Marshall’s left arm. The younger one was tall, had black hair, and wore a blue V-neck sweater. The only information police had was what Marshall himself had told them. Sergeant-Detective Michael MacDonald gave MacIntyre the description, but he didn’t attempt to find the men.

MacIntyre had no evidence, hadn’t searched Marshall’s home for a murder weapon, nor had he taken any formal statements from witnesses. Yet he decided within hours of taking over the investigation on May 29, 1971, that Marshall had stabbed Seale during an argument. He discussed the case with the RCMP during a meeting at the Sydney Police station. He believed the cut on Marshall’s arm was self-inflicted because it didn’t line up with the tears in the yellow jacket he was wearing. Then he interviewed teenagers John Pratico, sixteen, Chant, fifteen, and Patricia Harriss, fourteen. The information they provided didn’t support his theory. He interrogated them until they provided statements incriminating Marshall.

Pratico had consumed twelve to sixteen beers, and about one-and-three-quarter litres of wine before, during, and after the dance at the church hall the night of the stabbing. He first heard about the incident when it was mentioned on the radio the next morning. He learned more details when Marshall happened to walk by his house later that day. Another boy told police that Pratico had information about the stabbing. During questioning on Sunday, May 30, Pratico told MacIntyre that he knew nothing about the stabbing. But he sensed that the burly, intimidating, six-foot MacIntyre didn’t believe him. It was standard police practice to have a parent present during questioning, but MacIntyre spoke to Pratico alone.

A week later, on June 4, feeling pressure from MacIntyre, the sixteen-year-old gave a different statement. MacIntyre told him he could go to jail if he didn’t tell the truth. Pratico then told MacIntyre that he was sitting behind some bushes in Wentworth Park drinking more beer when he saw Marshall and Seale argue. Then Marshall took out “a shiny object” and stabbed Seale. Pratico, a jumpy, nervous teenager, had been under psychiatric care since August 1970. In 1982, Dr. M. A. Mian, medical director of the Cape Breton Hospital, would say in a sworn affidavit that Pratico suffered “from a schizophreniform illness manifested by a liability to fantasize and thereby distort reality” and a “rather childish desire to be in the limelight.”[1]

On May 30, 1971, detectives MacIntyre and William Urquhart interviewed Chant. In his first statement to police, Chant said that he was walking through the park on his way home when he ran into Marshall. He said Junior told him there had been a stabbing and asked for help. The two detectives interviewed Chant again on June 4. As the interrogation progressed, police told his mother, Beudah Chant, that her son would talk more openly if she weren’t present. She agreed to leave the room. The burly MacIntyre reminded Chant that he was on probation and that he could be sent to jail if he didn’t tell the truth. The police were convinced that he had seen more than he was telling. As Chant sat alone, MacIntyre accused him of lying in his previous statement and said he could be jailed for up to five years for lying. He was told that another witness had placed him near the scene of the stabbing. That witness was John Pratico. As with Chant, he wasn’t even in the park when Seale was stabbed. A frightened Chant just wanted to get out of the room. He decided to tell police what they wanted to hear so that he could get the interrogation over with. The fifteen-year-old signed a five-page statement in which he claimed to have witnessed Marshall stab Seale. The police brought him to Wentworth Park, where they helped him fill in the details of his testimony. “I didn’t feel I was being told what to do, but suggestions were offered, such as ‘Could you have been standing here, you could have seen it more clearly,’” he later said.[2]

Detective MacDonald had interviewed fourteen-year-old Patricia Harriss twice and her story was consistent. She corroborated Marshall’s story again when she gave detective Urquhart a statement at 8:15 p.m. on June 17. She said that she and her boyfriend were on their way back from the dance at St. Joseph’s when they saw Marshall talking to two men before the stabbing. Seale wasn’t with them. She gave a description of Ebsary that matched the one Marshall had given police earlier. Harriss wasn’t the only one to see Ebsary and his companion in the park the night Seale was stabbed. Teenagers George and Roderick McNeil went to the police station the next day. They said they were on their way back from the dance when they saw the two men ask a young couple for a cigarette. Sydney Police was given a detailed description.

Harriss didn’t have a chance to sign her statement before MacIntyre entered the room and began interrogating her again. Her mother, Eunice, only spent about an hour of the interrogation with her daughter before MacIntyre asked to speak to her daughter alone because she might be more forthcoming. Police didn’t believe Patricia had seen Marshall with the two men. Whenever she mentioned them, police crumpled up her statement and made her start over. She broke down and cried, but finally gave in. After five hours of questioning, she just wanted to leave. In her second statement, at 1:20 a.m. the next morning, she said she had seen Marshall and Seale together. But when she left the police station she was upset that police had told her what to say in her statement. As she later recalled in an affidavit to the RCMP in December 1982, “I found they (MacIntyre and Urquhart) were needlessly harping at me, going over and over telling me what they thought I should see … They took statements and changed them … My parents were not allowed in …”[3]

Once the police had statements from Chant and Pratico, they moved in to arrest Marshall on June 4, 1971. The Marshalls had received threatening phone calls after the fatal stabbing, so they had packed up their family and gone to his maternal grandfather’s home on the Whycocomagh reserve. The police drove to his grandparents’ house that evening and picked him up. As they took him back to Sydney, they said they had two eyewitnesses who said they saw him kill Seale. Marshall couldn’t believe his ears. He was placed in a cell at the Cape Breton County Jail.

MacIntyre believed that the gash on Marshall’s wound was self-inflicted. Once Marshall was behind bars, he wanted to get a sample of Marshall’s blood to strengthen his case. MacIntyre had the jackets Seale and Marshall had worn that fateful night, but there wasn’t enough blood on Marshall’s jacket to get a sample. MacIntyre asked a doctor at the Sydney hospital to take a sample while removing Marshall’s stitches. But Marshall had removed the ten or twelve stitches himself using a pocketknife. MacIntyre had no murder weapon, but that didn’t matter.

The case was handed to an experienced crown prosecutor, Donald C. MacNeil. He had been censured by the province’s human rights commission the previous year for comments he made in court on the lawlessness of Aboriginals. To solidify Pratico’s testimony, MacNeil and MacIntyre brought the teenager to Wentworth Park. They showed him where the mortally wounded Seale was found. They also said they had found a beer bottle with Pratico’s fingerprints and offered details to help him remember his story. But the strain of carrying around a lie took its toll on Pratico. Following a preliminary hearing in July 1971, Marshall was committed to stand trial on non-capital murder. In late August, Pratico had an emotional breakdown and was driven to a psychiatric hospital 430 kilometres away in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. He made the trip in a Sydney Police cruiser. A heavily-sedated Pratico was driven back to Sydney shortly before Marshall’s trial got underway.

Marshall’s family hired Sydney criminal lawyers Moe Rosenblum and Simon Khattar. Donald MacNeil didn’t give them copies of the contradictory witness statements. The defence lawyers weren’t aware that Chant, Pratico, and Harriss had given two different statements to police. For their part, Marshall’s lawyers were dubious that their client was telling the truth about the events that led to Seale’s fatal stabbing, including meeting two men who were dressed like priests. Although they were paid enough money to mount a proper defence, they didn’t check out Marshall’s story about being stabbed by an older man in a long coat, nor did they interview any of the Crown’s witnesses before the trial or investigate their stories and backgrounds. Had they done so, they would’ve learned that Pratico was sent to a psychiatric hospital after the preliminary hearing and Chant was on probation when police interrogated him. Instead, they relied on an incarcerated Marshall to give them leads.

On November 2, 1971, Junior Marshall was brought, handcuffed, to the Cape Breton County Courthouse, just blocks from Wentworth Park where Seale was stabbed. People had lined up on the steps of the law courts hoping to snag one of the hundred seats in the second-floor courtroom where he would be tried. His trial for non-capital murder got underway in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia before Mr. Justice J.L. Dubinsky.

Before Pratico, the Crown’s star witness, was put on the stand in the Sydney courthouse, he made a last-ditch effort to tell the truth about what he really knew about the stabbing. During a recess, Pratico walked over to Marshall’s father. Donald Sr. called over County Sheriff James MacKillop and the defence lawyer Simon Khattar to hear what Pratico had to say. They were soon joined by Detective MacIntyre and the prosecutor, Donald C. MacNeil. They all went into a small room to discuss the evidence. Pratico said that Marshall didn’t stab Seale. But moments later a frightened Pratico went back into the courtroom and lied. He said that he was drinking beer behind a bush when he heard Marshall and Seale argue before Marshall pulled out a shiny object and plunged it into Seale’s abdomen. Rosenblum tried to discredit Pratico’s story by pointing out that he was drunk at the time of the murder and that he had said on other occasions that Marshall hadn’t stabbed Seale. But when MacNeil and the defence tried to question Pratico about recanting his story in the courthouse hallway, Justice Louis Dubinsky told them to confine their questions to the night of the stabbing. Khattar wasn’t able to find out why Pratico lied. That may have left the jury with the impression that Pratico had been intimidated by Marshall and his father into saying he hadn’t seen the stabbing. Little did they know that Pratico hadn’t been near the crime scene.

Harriss was having second thoughts, too, but police led her to believe that she would go to jail if she didn’t stick to the second statement she gave police, which said that Marshall and Seale were the only ones she saw in the park before the stabbing. Chant, a fifteen-year-old grade seven student from nearby Louisbourg, who had repeated a couple of grades, said that was heading home when he saw Pratico behind a bush watching two people on Crescent Street and witnessed the stabbing. Under cross-examination he admitted that he couldn’t positively identify Marshall as Seale’s assailant. He was declared a hostile witness.

Marshall was the only defence witness that Rosenblum called to the stand. The judge had to repeatedly remind the soft-spoken Marshall to speak up and stop covering his mouth with his hand. He testified that he was talking to Seale in Wentworth Park at about 11:00 p.m. when two men in long coats or cloaks approached asking for a cigarette and a light. They said they were priests from Manitoba and asked if there were any women in the park. Then the older man said “we don’t like Niggers or Indians,” pulled out a knife and stabbed Seale in the abdomen. He then slashed Marshall’s left arm with the knife. The trial was an ordeal for the young Marshall, who had just turned eighteen behind bars. He asked for and was given medication to help him through.

Jurors deliberated for four hours. Despite the absence of a murder weapon and the lack of motive, they ultimately chose to believe Pratico’s testimony and the Crown’s contention that Marshall’s wound — next to a tattoo of the words “I hate cops” —was self-inflicted. On November 5, 1971, Marshall was found guilty of non-capital murder. He sobbed as he was convicted that afternoon and sentenced to life in prison.

Racial prejudice was an issue for at least one juror. In an interview with The Toronto Star more than a decade later, one juror said there was no racism at play during the trial, but he also told a reporter, “With one redskin and one Negro involved, it was like two dogs in a field — you knew one of them was going to kill the other. I would expect more from a white person,” he said. “We are more civilized.”[4] Marshall was taken to prison. Pratico returned to the Nova Scotia Hospital just before Christmas in 1971. He would continue to be in and out of psychiatric hospitals for the next decade.

Ten days after Marshall was convicted, a guilt-ridden Jimmy MacNeil went to the Sydney Police to tell them the wrong man was behind bars for Seale’s murder. He never thought Marshall, an innocent man, would be convicted. On November 15, 1971, he told MacIntrye that he had witnessed the stabbing. Roy Ebsary was the real killer. Ebsary was a vegetable cutter who had served with the Royal Navy during the Second World War. Under questioning, he admitted that he was in Wentworth Park that night but denied that he stabbed anyone. Police also interviewed Ebsary’s common-law wife, Mary, and son, Greg. He told police that his father was fascinated with knives and often carried one with him. They didn’t interview his sister, Donna, who had witnessed her father washing blood from a knife after Seale’s murder.

On November 17, a criminal-records check revealed that MacNeil had no prior convictions. However, Ebsary had one breach of liquor laws and a conviction for possession of a concealed weapon — a knife. The file with MacNeil’s statement was sent to assistant prosecutor Lewis Matheson. He informed Deputy Attorney-General Robert Anderson and handed the file to the RCMP. (At a public inquiry, Anderson admitted that during a private conversation with Marshall’s lawyer Felix Cacchione in 1984 he may have said, “Felix, don’t get your balls caught in a vise over an Indian.” He claimed at the inquiry that his comment was based on Marshall’s reputation rather than his race.)[5]

RCMP Inspector Ernest A. Marshall (no relation) and Constable Eugene Smith arrived in Sydney on November 16, 1971, and conducted a brief investigation. Inspector Marshall had been on the force for thirteen years and had developed a friendship with MacIntryre during the six years he worked in the Sydney area. He and Constable Smith spoke to MacIntyre, who was convinced that he had the right man. Constable Smith administered polygraph tests to Ebsary and MacNeil at a motel on November 23. Smith had been trained in polygraph science at New York’s National Training Centre of Polygraphic Science but he wasn’t yet certified as a technician. They concluded that Ebsary was being truthful but MacNeil’s test was inconclusive. Constable Smith put an end to it because MacNeil was shaking badly from alcohol detoxification. However, he didn’t resume the test when MacNeil’s problems disappeared. The RCMP closed the case without further investigation. They never re-interviewed Donald Marshall Jr. or any of the witnesses who testified at Marshall’s trial. As Constable Smith later admitted before an inquiry, they simply rubber-stamped the Sydney Police’s investigation.

While the investigation cast doubt on Marshall’s involvement in Seale’s murder, his lawyers, who were appealing the teenager’s conviction to the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal, were not informed about the new evidence. They also failed to raise a legal error that the trial judge had made when he stopped them from questioning Pratico about recanting his evidence. They lost the appeal in January 1972.

Marshall languished in county jail until June 20, 1972, when he was finally sent to maximum-security Dorchester Penitentiary in New Brunswick. He was transferred to the medium-security prison in Springhill in January 1975. While in prison, inmate 1997 went back to school and earned a certificate as a plumber. He passed the time playing hockey and baseball and running. Throughout his incarceration in Dorchester and Springhill penitentiaries, Marshall continued to maintain his innocence. A chain around his neck with an inscription from Isaiah, “No weapon formed against you shall prosper,” helped give him hope that one day the truth would set him free.

An application for a three-day pass to spend Christmas 1977 with his family was turned down. Marshall believed it was because he refused to admit that he had killed Sandy Seale. They also refused to allow him to attend his grandmother’s funeral. MacIntyre, who by then had become Sydney’s police chief, was against allowing Marshall to receive unsupervised temporary absences. He said he was concerned that Marshall would seek revenge against witnesses.

For their part, prison staff continued trying to get Marshall to admit to the murder. Marshall refused. He wrote letters to politicians trying to get his case reopened, to no avail. In a 1972 report, while Marshall was incarcerated at Dorchester Penitentiary in New Brunswick, a staff member wrote, “Marshall is a typical, young Indian lad that seems to lose control of his senses while indulging in intoxicating liquor.”[6]

In October 1979, he escaped while returning to Springhill Penitentiary from a wilderness camping trip for prisoners near New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. He made his way to his girlfriend’s house in Pictou and was recaptured there several days later. He was charged with being unlawfully at large and sent to the maximum-security Dorchester Penitentiary in New Brunswick. While he was in prison, Marshall broke his wrist in a hockey game, but the prison doctor told him it was just a ganglion. Eight years later, an X-ray at a civilian hospital in Springhill revealed two broken bones in his wrist that had rotted away and died. He had surgery to repair the damage.

Marshall’s incarceration also took an emotional and financial toll on his family. His parents were devastated and his father had nightmares. Marshall Sr. had to get an unlisted telephone number after his son was arrested because of threatening phone calls. His drywall and plastering business suffered. Each time he and his wife visited their son, they spent about $200 to travel more than 500 kilometres from the Membertou reserve to Dorchester, New Brunswick. At one time, the family had to rely on welfare to get by.

Meanwhile, the Sydney Police Department continued to receive information that they had the wrong man behind bars. In 1974, martial-arts instructor Dave Ratchford went to police a day after Ebsary’s sixteen-year-old daughter Donna told him that her father was Seale’s killer, not Marshall Jr. But Detective Urquhart said the case was closed.

While Marshall was imprisoned at Dorchester, a friend came for a visit and brought along a young man who had boarded with Ebsary. He said Ebsary admitted that he killed Seale. Marshall wrote Ebsary a letter. Ebsary replied that he knew Marshall wasn’t Seale’s killer and promised that he would get Marshall out of prison. Marshall sent copies of the letter to the parole board and the Sydney Police. He also contacted Halifax lawyer Stephen Aronson. On December 5, 1981, another stabbing occurred in Sydney. Ebsary was charged and convicted of the offence.

The RCMP began reinvestigating the case in February 1982 after Aronson wrote to the RCMP telling them that Mitchell Sarson of Pictou, Nova Scotia claimed Ebsary had committed the Seale murder. Staff Sergeant Harry Wheaton and Corporal James Carroll carried out the investigation under the supervision of Inspector Don Scott, commanding officer of the Sydney detachment. They were assigned to the case on February 3, 1982.

They met with MacIntyre, who produced two witness statements from Harriss and her boyfriend, Terry Gushue. A comment that MacIntyre allegedly made also raised eyebrows. MacIntyre said he wasn’t able to get a blood sample from Marshall because Marshall removed his own stitches from the minor knife wound he sustained during Ebsary’s attack. Wheaton asked why MacIntyre failed to ask Marshall’s doctor, Dr. Mohan Virick of Sydney (who was East Indian), for the sample. MacIntyre replied, “Those brown-skinned fellows stick together.” [7] MacIntyre also claimed that Marshall had escaped prison in 1979 by paddling a canoe more than 250 kilometres to Pictou, Nova Scotia. In fact, Marshall walked and hitchhiked.

Wheaton and Carroll were stunned by what they uncovered. Pratico, Chant, and Harriss all recanted their testimony, saying that they had been pressured by the Sydney police to lie. Chant, a born-again Christian, had told his parents and his pastor that he lied during Marshall’s murder trial. He was relieved to finally tell police the truth. Wheaton and Carroll interviewed Marshall at Dorchester Penitentiary on February 18, 1982, and March 3, 1982. The two concluded that Marshall was innocent.

When Wheaton and Corporal Herb Davies went to MacIntyre’s office in April 17, 1982, to question him about his original 1971 investigation, the burly detective was less than forthcoming. When the two RCMP officers left MacIntyre’s office, Davies told Wheaton that he had seen MacIntyre slip papers under his desk. Wheaton returned and confronted MacIntyre, who handed over the first statement that Patricia Harriss made to police in which she exonerated Marshall. But it wasn’t the first time that MacIntyre had told the RCMP that he had handed over the entire contents of the file when in fact he hadn’t.

Investigators finally found the murder weapon when Ebsary’s estranged common-law wife allowed the police to search the basement of the home they once shared. Fibres from the clothing that Seale and Marshall were wearing the night of the fatal stabbing were found on the knife. The RCMP also interviewed Ebsary’s daughter, Donna, who had seen her father wash the blood off his knife the night that Seale was stabbed. There was finally enough evidence to cast doubt on Marshall’s conviction.

On March 26, 1982, the parole board informed lawyer Aronson that Marshall would be released. After spending nearly eleven years behind bars for a murder he didn’t commit, Marshall walked out of Dorchester Penitentiary on March 29, 1982. He was twenty-eight years old. His parents were waiting to drive him from Moncton to Carleton House, a halfway house in Halifax. One of his first requests was to visit the fishing village of Peggy’s Cove to see the ocean. The following day, on March 30, 1982, Ebsary, then aged sixty-nine, was sent to the Nova Scotia Hospital in Dartmouth to undergo a court-ordered psychiatric exam before being sentenced for the December 1981 stabbing.

Aronson appealed to federal Justice Minister Jean Chrétien to grant Marshall a full pardon, which would recognize that Marshall never committed the offence. Under what was then Section 617 of the Criminal Code, Chrétien could order a new trial, refer the matter to the appeals court, or ask the appeals court to rule on specific questions related to the case. Chrétien was apparently outraged about Marshall’s wrongful conviction, but he was advised by his staff to refer the matter to the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal. In June 1982, Chrétien referred the case to the appeals court on the basis that new evidence uncovered by the RCMP had come to light. The court could order a new trial, declare Marshall not guilty or uphold his conviction. “All I want,” Marshall told The Globe and Mail reporter Michael Harris, “is what belongs to me, my freedom.”[8]

The Appeal Division of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court held a hearing on October 5, 1982, to consider the new evidence. Marshall sat quietly, dressed in a blue V-neck sweater, blue-gray slacks, a shirt, and tie. He had moved into an apartment and gotten a job as a Native education counselor with the federal Indian Affairs Department. The evidence was presented before Chief Justice Ian MacKeigan and Justices Gordon Hart, Malachi Jones, Angus L. Macdonald, and Leonard Pace, who was attorney general when Marshall was convicted in 1971. It included affidavits from John Pratico and Maynard Chant admitting they didn’t witness the fatal stabbing and weren’t even at the scene when it happened. Patricia Harriss recanted her testimony as well. She said her first statement to police about seeing Marshall with two men the night of the murder but not seeing Seale was the truth. The Sydney Police detectives filed affidavits saying the second statements from the witnesses were obtained because they believed Marshall had influenced the witnesses in their initial statements. The five justices heard applications from Crown Prosecutor Frank Edwards and defence lawyer Aronson. They decided to hear evidence from seven witnesses on December 1 and 2, 1982, including Marshall, Maynard Vincent Chant, and an RCMP fibre expert. James William MacNeil, the thirty-seven-year-old unemployed labourer who had been with Ebsary at the time of the murder, testified that Ebsary stabbed Seale during a scuffle when the teenagers tried to rob them. Then they went back to Ebsary’s house and he watched him stand at the kitchen sink and wash blood off the knife. Ebsary’s daughter, Donna, testified that she watched her father clean the knife and that he then took it upstairs to his room. She said he was fascinated with knives and had a grindstone in the basement. He was a violent man, she said, who had killed her cat and her budgie in a rage. Her brother, Greg Ebsary, identified the murder weapon as belonging to Roy Ebsary. Both Chant and Harriss recanted their 1971 testimony that helped convict Marshall and said they were pressured by police to change their statements. Marshall admitted that he wanted to get money when he was in the park, but he denied that he and Seale tried to rob Ebsary and MacNeil. RCMP forensics expert James Evers from the crime lab in Sackville, New Brunswick, said the knife had twelve fibres on the blade that were consistent with material from the coats that Seale and Marshall wore on May 28, 1971.

When the court hearing resumed on February 16, 1983, Crown prosecutor Frank Edwards and defence lawyer Aronson argued for just forty-five minutes that the five Supreme Court judges quash Marshall’s conviction and acquit him of murdering Sandy Seale. Aronson argued that a miscarriage of justice had occurred. But Edwards argued that Marshall was “the author of his own misfortune to a very large degree.”[9]

On May 10, 1983, more than a year after Marshall was released from prison, lawyer Stephen Aronson phoned the band office at the Membertou reserve to announce that the five judges of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia unanimously acquitted Marshall of the murder of Sandy Seale. The band office emptied as people ran from one house to another to share the news that Junior was free. Marshall learned the news from his tearful mother when he went to Victoria General Hospital in Halifax to visit his father who was suffering from kidney failure. For Caroline Marshall, “It was the best Mother’s Day present I’ve ever had, even if it was late.“[10]

But in a portion of the sixty-six-page decision that would hinder Marshall’s efforts to obtain compensation from the province, the judges picked up on the Crown’s argument and blamed him for being the author of his own misfortune. They said that any miscarriage of justice in his case was more apparent than real. “In attempting to defend himself against the charge of murder Mr. Marshall admittedly committed perjury for which he could still be charged. By lying he helped secure his own conviction.… By planning a robbery with the aid of Mr. Seale he triggered a series of events which unfortunately ended in the death of Mr. Seale.”[11] The judges made no reference to the perjury committed by three witnesses in Marshall’s original trial. They also exonerated the police and the Crown while convicting Marshall for an offence for which he was never charged.

Aronson and Marshall were pleased with the decision but wanted a public inquiry to be called to determine how an innocent man came to be convicted of murder. Marshall had also amassed a legal bill of $79,000 for his acquittal, which he was unable to pay. Aronson said the Union of Nova Scotia Indians and the federal government both told him the bill would be paid. For its part, the provincial government refused to pay despite the fact that the administration of justice is under provincial jurisdiction. Having run out of money, Aronson left private practice and took a job with the federal government. But he didn’t regret the work he did for Marshall’s release. “I will always look forward to seeing this guy. What he’s done in the last year, after spending 11 years behind bars is absolutely amazing. During the last year he’s remained normal while I’ve grown less trusting and more cynical about the workings of the system.”[12]

On May 12, 1983, two days after Marshall was acquitted, Roy Newman Ebsary was finally charged with second-degree murder in the death of Sandy Seale — twelve years after Seale was stabbed to death. The charge was reduced to manslaughter at his preliminary hearing in August 1983. Ebsary pleaded not guilty on the grounds of self-defence. On September 12, 1983, his lawyer, Luke Wintermans, tried to have the charges dropped on the grounds that too much time had elapsed between the offence and Ebsary’s trial. Justice Lorne Clarke of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court dismissed the motion. Before a jury of eleven men and one woman, Wintermans claimed that Ebsary was defending himself when he stabbed the unarmed Seale. After a one-day trial and ten hours of deliberations, the jury couldn’t come to a decision. Ebsary was released on his own recognizance pending a new trial. This was in contrast to twelve years earlier, when Marshall was taken from the courtroom in handcuffs and shackles. Noel Doucette, then president of the Council of Nova Scotia Indians, and a fourteen-year member of the provincial Human Rights Commission, was upset. “It’s a sad irony. Twelve years ago Donald Marshall (a Micmac) came into this same courtroom in shackles. It took a white jury only 45 minutes to convict him. Then you see Ebsary, a white man just walk in and out of here as if he had done nothing at all. It’s justice for the white man and for the Indian; it’s the law.”[13]

Ebsary’s second trial began two months later, on November 4, 1983, before Mr. Justice R. McLeod Rogers of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court. This time, prosecutor Edwards played a tape recording of a twenty-minute conversation between Ebsary, seventy-one, and Corporal James Carroll, a twenty-three-year veteran of the RCMP. In it, Ebsary described the sequence of events that occurred in Wentworth Park on May 28, 1971, and how he stabbed Seale and slashed Marshall’s arm, then went home, fired up a barbecue, and cooked up some steaks. Ebsary claimed Marshall had fatally stabbed Seale to “finish him off.” He was found guilty of manslaughter. Donald Marshall Sr. raised a clenched fist in victory. After years of public shame about his son’s conviction, the right man was finally convicted. On November 24, 1983, Ebsary was sentenced to five years in prison in the same courtroom where Marshall was sentenced to life behind bars twelve years earlier.

But it was not over. Ebsary was released on bail pending an appeal of his conviction. The Nova Scotia Supreme Court Appeals Division ordered a new trial on September 11, 1984. Chief Justice Ian MacKeigan ruled that the trial judge in November 1983 gave the jury incorrect instructions on whether Ebsary acted in self-defence when Seale and Marshall confronted him. Ebsary’s third trial got underway in January 1985 before Justice Merlin Nunn. As Ebsary was found guilty on January 17, 1985, Marshall sat in the back of the courtroom and wept quietly. On January 30, 1985, Ebsary was sentenced to three years in prison but his lawyer appealed. On May 12, 1986, the Nova Scotia Supreme Court upheld Ebsary’s manslaughter conviction but reduced his sentence from three years in prison to one year in county jail. The Supreme Court said it reduced the sentence because of Ebsary’s advanced age and failing health and because there was an element of self-defence. On October 9, 1986, the Supreme Court of Canada refused Ebsary leave to appeal the conviction. He served his one-year sentence at the Cape Breton County Correctional Centre near Sydney. The tiny, frail eccentric lived the final years of his life in Sydney rooming houses, estranged from his longtime common-law wife and their two children.

Compensation for Marshall’s eleven years behind bars and a public inquiry into his wrongful conviction proved to be another battle he would have to fight. The federal government argued that it was up to the Nova Scotia government to compensate him since the administration of justice is under provincial jurisdiction. Nova Scotia’s attorney-general initially said that Marshall’s Aboriginal status made him a federal responsibility. Marshall wanted $1 million in compensation, taking into account his loss of freedom and pain and suffering during his incarceration. During negotiations with the provincial government, which began in June 1984, Marshall’s lawyer, Felix Cacchione, also cited a New Zealand case in which a wrongly convicted person received $1.3 million in government compensation and an American case in which $1 million in compensation was paid. But the provincial government’s position was to pay Marshall as little as possible. The final settlement wouldn’t take into account the botched police investigation. They didn’t believe that a miscarriage of justice had occurred.

Cacchione was denied access to the provincial government’s files on Marshall’s case, giving the government an advantage during compensation negotiations. As Reinhold Endres, the government’s chief negotiator, later testified at a royal commission into Marshall’s wrongful conviction, the province wanted a settlement that was as low as possible. “My concern was not that justice be done for Mr. Marshall,” he said. “The way I approached it was how far down we could come from that figure.”[14] In the appeal that acquitted Marshall, the Nova Scotia Supreme Court justices said that a miscarriage of justice in the case was more apparent than real because the murder occurred when he was involved in an alleged mugging. (The word “alleged” is used by the author because Marshall was never tried for the offence and there were questions as to whether a robbery even occurred.)

In September 1984, tired of fighting what seemed like yet another uphill battle, Marshall settled for $270,000 in compensation from the province of Nova Scotia. He agreed, in return, not to take any legal action against the Crown for his wrongful imprisonment. Compensation included $97,000 in legal costs he incurred to prove his innocence and get compensation. Cacchione and Aronson reduced their legal bills. Aronson received $70,000 and Cacchione got $27,000, but this still left Marshall with only $173,000 for nearly eleven years behind bars. That amounted to $43.79 a day for nearly 4,000 days in prison. The federal government agreed to cover half of the compensation. A fund that Montreal United Church minister Robert Hussey set up collected another $45,000 for Marshall. As Cacchione told The Globe and Mail in an interview, “This is not a happy ending. This is partial repayment of an unpayable debt.”[15]

Fifteen years after Marshall was wrongly convicted, the Nova Scotia government appointed a royal commission, in October 1986, to examine the circumstances that led to Marshall’s wrongful conviction, as well as the administration of criminal justice in the province. Alexander Hickman, chief justice of the Newfoundland Supreme Court’s trial division, headed the commission. The other members were Associate Chief Justice Lawrence Poitras of the Quebec Superior Court and Chief Justice Gregory Evans of the Ontario Supreme Court.

About eighty people packed the basement hall of St. Andrews United Church, just blocks from where Seale was murdered, when the inquiry got underway in Sydney on September 9, 1987. During the inquiry, the three commissioners learned that the police investigation was shoddy: the crime scene wasn’t sealed off and searched for clues, bystanders weren’t questioned, no autopsy was performed, a description that Marshall gave police wasn’t circulated to officers on patrol, and police didn’t search files looking for someone fitting Ebsary’s description. The Crown also failed to give the defence copies of witnesses’ contradictory police statements, and defence lawyers failed to request them. Witnesses agreed that full disclosure did not exist in Nova Scotia. The trial judge didn’t allow the defence to question a witness about his admission in the hallway outside the court that his testimony about witnessing Marshall stab Seale was a lie. Marshall’s lawyers failed to raise this legally incorrect ruling during their 1972 appeal. A 1971 RCMP re-investigation of the case simply rubber-stamped the original Sydney Police investigation. Frank Edwards, the prosecutor in Marshall’s 1983 appeal hearing, wanted to argue for an acquittal on the grounds that there was a miscarriage of justice. But he was directed by deputy minister Gordon Coles to argue that Marshall was partly to blame for his wrongful conviction. The five appeal justices who blamed Marshall for his wrongful conviction reached their conclusion in 1983 based on statements and affidavits that were filed but weren’t formally introduced before the court. This meant that the Crown and defence counsel couldn’t make submissions about them or cross-examine people who made the statements to which the judges referred in their ruling.

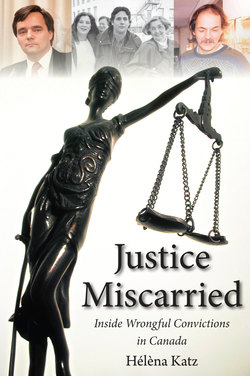

Justice Alexander Hickman headed the Commission of Inquiry into Donald Marshall’s wrongful conviction. Courtesy of Justice Alexander Hickman