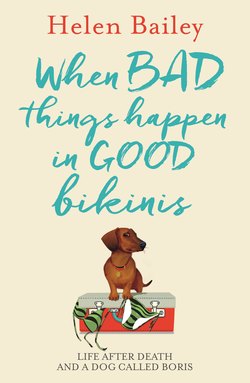

Читать книгу When Bad Things Happen in Good Bikinis - Helen Bailey - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

DOGGONE

ОглавлениеThe morning my husband was killed, we were due to go away for the weekend. I was ironing and packing as he said goodbye. He was just ‘popping along the road’ being driven by a friend. He didn’t come back. It happened one minute from home. I was ironing and he was dying and I DIDN’T KNOW. How can that be possible? ~ Emma A

I’m a list-maker. I make so many lists, sometimes I have to make a list of the lists I’ve made. Personally, I don’t think list-making comes high on my list (ha!) of vices, but that was before I read an article which warned that women were becoming slaves to their lists, that instead of giving them control, the lists were controlling them in a vicious cycle of ticking things off and adding stuff on. ‘Loosen up your lists!’ the article advised. ‘Renounce listmania!’

I gave it a whirl when we had friends round for a meal. Instead of instructions taped to the inside of a kitchen cupboard door (7:00pm: Put oven on to 170; 7:05pm: Double check oven is on, etc.), I went (list-wise) commando.

It was a disaster. Instead of wafting around the kitchen in a state of list-less bliss, I forgot to do pretty much everything but drink alcohol.

Making lists comes naturally to me. I find lists a way of keeping some control in my life, and never has my life been more out of control than it has been in the last 23 weeks. So, as bizarre as it now sounds, I decided to make a list of ways in which, pre-accident, I could have imagined losing my husband: cancer; car crash; heart attack; brain tumour; slipping on ice and banging his head on the kerb; carjack at gunpoint on the Holloway Road; some DIY disaster involving a ladder and electricity – dammit, even perishing by terrorist attack on the Northern Line made it onto the Death List. But walking into a calm, turquoise-blue sea whilst on holiday and drowning? It never once crossed my mind.

I ached to talk to JS about his death, to say, ‘You know all those times I freaked out that I would lose you because [insert Doomsday scenario here]? Actually, this is how it all ended . . .’ I couldn’t imagine what he would say. It was so inconceivable; it was unimaginable.

I could imagine him rationalising other deaths:

Cancer: ‘Well, we knew there was a lot of it in the family.’

Car crash: ‘I’m surprised I didn’t have a serious prang earlier.’

Terrorism: ‘Even the tightest security can’t stop a nutter stuffing Semtex up their jumper.’

Heart attack: ‘So much for the expensive BUPA ECG test!’

But had I said to him one night, whilst sitting on the sofa watching Top Gear, ‘I’m worried one day I’ll be in my bikini on a beautiful beach and watch you drown,’ he’d have felt my forehead and asked whether I was delirious or been at the cooking sherry.

A few months after the accident and in major self-pity mode, I trudged tearfully around Hampstead Heath with The Hound, wondering just how many people are unlucky enough to have lost both a husband and a beloved dog whilst on holiday. Yes, dear reader, a death en vacance has happened to me before, which is why I doubt I will ever need my (still packed) suitcase again, not that anyone will want to accompany me given that clearly the Grim Reaper sneaks into my luggage.

In early March 2008, I travelled with JS and our dachshund, Rufus, from London to Northumberland to spend a week in Embleton, a tiny village on the north-east coast. The weather was glorious when we arrived, so we unpacked the car and rushed straight to the beach. Rufus went wild with excitement, zooming over the sands and along the dunes. We laughed at him careering about. ‘What a lucky dog he is!’ I remember JS saying fondly.

A few hours later, back in the cottage, we heard the dog repeatedly sneezing in the kitchen. I went to investigate and found the room covered in blood, as if someone had been shot against the fridge-freezer. Rufus seemed fine: he was wagging his tail, excitedly licking blood off the floor. I was confused. Surely if he’d cut his paw he’d be in pain or licking the wound? Then he sneezed again, and blood splattered everywhere.

I rang the vet who told us to bring Rufus in. JS drove like the clappers in the dark through the country lanes to the surgery. The vet asked us to sit in a nearby pub for an hour whilst he examined the dog. I remember going to the loo and realising that my face, hands and clothes were covered in blood; JS was so distraught, he hadn’t realised I was doing a Jackie Kennedy impression, but in jeans and a rugby shirt rather than a pink designer suit. We must have stood out like sore thumbs: it was Saturday Karaoke night, and all the Geordie lasses were in their pelmet skirts and plunging tops, belting out ‘I Will Survive’ whilst clutching luminous bottles of alcopops. I wanted a clear head, so had a cup of tea and a packet of cheese and onion crisps.

We went back to the surgery. The bleeding had worsened. The dog with the waggy tail was now sedated and kept in overnight. We were still wide-awake and rigid with anxiety in the early hours of Sunday morning when the vet rang with his diagnosis: the back of Rufus’ throat – his soft palette – had completely ripped apart. The vet didn’t know for sure, but it seemed likely that Rufus had an undetected tumour that had burst, probably by running on the beach. It was a bomb waiting to go off, and it went off on our holiday. As my husband wailed and paced the bedroom of the rented cottage, I made the only decision I could, to allow the vet to increase the sedation and put our beloved friend to sleep. Three of us had arrived on holiday a few hours before. Now we were two. I make no apologies for confessing that Rufus was our child substitute, that we had both poured an unhealthy amount of emotion and love into the little lad. And now he was gone.

We both wanted to go home immediately, but with no sleep we were too tired to drive the 300 miles back to London. On the Monday, instead of packing a rucksack with a picnic and heading off on a walk, we went back to the surgery to sign forms, pay the bill, get Rufus’ red leather collar and arrange for him to be cremated. We spent days sitting in coffee shops, tearful, passing time, not wanting to go home, not wanting to stay. We barely ate; we couldn’t sleep. We were both heartbroken, but I remember JS saying that as long as we had each other, we’d be OK. Together, we could get through anything.

Going home without Rufus was traumatic; walking through the front door without him rushing ahead of us, harrowing. Life felt empty, the house soulless. Even work was no escape: he had been an office dog since he was ten weeks old. Staff cried.

As I walked on the Heath with The Hound, the similarities to what had happened almost exactly two years apart felt profound, even down to the Sunday morning holiday deaths. As bizarre parallels swirled around my brain, I was amazed that I hadn’t thought of them before.

And then I remembered what JS had said when people commiserated about how awful it must have been to lose Rufus on holiday. I remembered it as clearly as I could remember my own name, and it literally took my breath away. JS said, ‘Oh, he had the most wonderful death. He had a great life and a fantastic last day on the beach. He didn’t get ill or suffer. He went out with a bang. Wouldn’t we all like to go like that?’

JS wouldn’t have wanted his family to suffer and the timing was rotten, but I now know what my husband would say about his own death.

The problem is, back then JS was right when he said we could get through anything, together. But we’re no longer together. I’m alone. And I haven’t lost my dog. I’ve lost my husband.