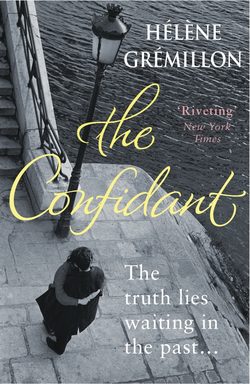

Читать книгу The Confidant - Helene Gremillon - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIt is not other people who inflict the worst disappointments, but the shock between reality and the extravagance of our imagination.

Annie and I always walked together from school to the haberdashery. We never left at the same time, but the distance between us gradually shrank along the way. Whoever was walking in front would slow down, while the one behind picked up speed, until the two of us were walking side by side.

But years later, when we met again – on 4 October 1943, in Paris – Annie laughed and said I was the one who played both parts: either I caught up with her, or I let her catch up with me, but as far as she was concerned she swore she had never adjusted her speed. I did not seek to deny it; it was true that I wouldn’t have missed those walks with her for the world. In my mind, I called them our ‘lovers’ strolls’ – words often help to rearrange the nature of things. It was true, too, that I had long hoped for something between us, but things had turned out differently. She must have been married by then; at twenty, that was normal – I had deliberately aged her a year or two, to hurt her feelings a bit. I had seen the wedding ring on her finger. I was pretending. I was playing the part of the man who does not chase after women, who no longer hopes. The man whom one need not fear. As a child I had never used any tricks to secure her affections, but on that 4 October 1943, with my eyes glued to the ground to avoid her gaze, I could hear myself saying the exact opposite of what I was thinking. I was obligingly opening the way for her to tell me whatever she liked, with no regard for the past. What of her life, today? Was she happy?

Oddly enough, Annie replied with a confession.

‘I must tell you, Louis, that you have always been the first. The first to kiss me, the first to caress my cheek, my breasts, the first who knew that there were days when I wore nothing under my skirt.’

Annie reminded me of all those first times; she remembered everything better than I did.

‘Why did you never tell me this?’

She looked up at me.

‘What’s the point in telling a man that he was the first? Do you tell the twelfth man that he was the twelfth? Or the last that he was the last?’

I did not know what to say.

Did she hope, by pouring out all her memories, that I would forgive her for everything that never happened between us? The truth is, she began to change when she first started spending time with that Madame M.

Annie stood up abruptly, as if suddenly embarrassed to be near me. She offered me a chicory coffee, apologising that, because of the rationing, she no longer had any real coffee, or any sugar. She was nervous, opening all the cupboard doors as if she didn’t really know what she was doing. Her apartment was very small. I watched her bare feet moving about her few square metres of living space. Her kitchen – a sink and a hot plate – was next to her bed, fortunately, for had she so much as left the room I might have doubted her very presence. I hadn’t seen her for three years. For three years I’d had no news of her at all. At no time did I suspect she might be living in Paris like me. I looked at her fingernails, her peeling red varnish; in the village she never used to wear any. Seeing her again like this: it seemed too good to be true. Outside it was pitch black. I was suddenly overwhelmed by desire for her. She handed me a steaming hot cup.

‘So, do you remember Monsieur and Madame M.?’

How could she ask me such a thing?