Читать книгу Escape to Africa - Henri Diamant - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление06. Father’s Career At Bata

I do not know why father abandoned his dream of owning and running his own store. Maybe it was on account of me. I was another mouth to feed and the growing family needed a decent and dependable income, the kind that one could not really expect from a small retail business. The company he was joining was known for great career opportunities, above average pay and exceptional benefits, such as the company-managed savings accounts that rewarded employees with the unheard of yearly yield of ten percent.

Without question, future events proved that father made the right decision to join the Bata organization. And, since he often spoke of those times, I was left with a good appreciation of what the company was all about, the company that eventually affected our lives to such a great degree.

The founder of the company, Mr. Thomas Bata, became an apprentice in his father’s modest footwear-manufacturing establishment during the late 1800s. By 1932, the year that he died in the crash of the company-owned airplane, he had transformed his hometown of Zlin, Czechoslovakia, into a modern industrial center that mass-produced some thirty-six million pairs of footwear per year. The town, about 150 miles east of Prague, was owned entirely by the company, and employed a total of 20,000 workers. It featured low-rent housing, free access to medical care, schools, a cinema, a great indoor market, a department store, and large athletic facilities where various company teams competed vigorously for trophies. It became a global enterprise, with an industrial center famous for its mass production techniques and up-to-date technology. It was the most modern enterprise in the country, wielding a huge economic impact on the young republic and, to some extent, the world across state borders. For instance, there was the time when the German railroads, which moved the bulk of Zlin’s exports to various German seaports (the Czech Republic being a land-locked country), informed the company about a substantial freight-rate increase. The company did not even bother to acknowledge receipt of the new rates, much less enter into any negotiations about them. Instead, it purchased a large fleet of trucks and started to do its own hauling across Germany. Within a few weeks, according to father, the railroads canceled the new freight rates, submitted some of the lowest rates ever, and took those dreadful trucks off the company’s hands by purchasing them at premium prices.

Father also mentioned a couple of other instances that I found really interesting. The first one had to do with the extraordinary concept (we must remember that we are talking about the1930s) that went into the making of the chairman’s office in the company’s new headquarters building. The architects installed it in an elevator that moved swiftly and quietly up and down the 16 floors of the headquarters. This saved the chairman’s time and kept the office personnel on its toes... no one knew when the boss would pop-up unannounced on their floor. By the way, the boss at that time was Jan Bata, he took over the management of the company after Thomas’ death. They were stepbrothers, and Jan remained in charge until Thomas Junior came of age.

The other instance tells of Bata’s entry into Africa. The initial decision to break into that market was made in the early 1930s, when the company charged two budding marketing managers to size up the business outlook on the continent. One was instructed to do his research up and down the East Coast, while the other was assigned to the West Coast. The one that had gone to the East Coast telexed the following discouraging news; “No one is wearing any footwear. No reason to waste time. Returning home”. Then headquarters received the now-famous telex from the second guy: “See great opportunity. Everyone here in need of their very first pair of shoes”. It is not difficult to guess which one of them was promoted quickly to a high management position in the expanding export division.

At any rate, once father made the move, he charged aggressively into his new job and, thanks to his prior experience in the retail business, easily impressed management during initial evaluation, and over the tough training period in Zlin. As a result, it did not take long before he was placed in charge of one of the low-volume shoe stores that were the training grounds for upcoming retail managers.

This store was located in the small town of Slavkov, a short distance from Brno, the second largest city in Czechoslovakia and the capital of the province of Moravia. And while it was a small town according to its size, it really was a giant by historical dimensions. History refers to it by the German name of Austerlitz, the place where a famous battle of the Napoleonic wars was fought on December 2, 1805. During that engagement, Napoleon’s small expeditionary force completely crushed the much larger army that had been hurled against it by a coalition of the Austrian and Russian military forces.

Outside of Slavkov, at a junction of the road leading to the highway that connects the cities of Brno and Olomouc, one can still have a meal at the Stara Posta Inn, the very same tavern that Napoleon used during the night of that famous December day, in 1805. The next morning, he went to Presburg to sign the Peace Treaty that forced Austria to relinquish Venice and the Tyrol, and paved the way for Napoleon to become the master of Central Europe. His reign ended in 1815, when he met his final defeat at the bloody battle of Waterloo, a small Belgian village some 10 miles southeast of Brussels. He was exiled to the island of Saint Helena, where he died of cancer in 1821. Napoleon Bonaparte’s body is buried in Paris, beneath the dome of the Hotel des Invalides, a hospital for sick and aged soldiers.

In 1933 father took over a large store in Sumperk, in the vicinity of the city of Olomouc. This promotion came with a substantial pay increase, an increase that motivated father to purchase the family’s first car. Having a car in those days was rather exceptional, and the fact that father could afford one was clear indication that, true to its reputation, the company never failed to link pay to performance and hard work.

Another noteworthy event happened that year. Harry started his formal education and entered first grade. How fitting that he reached this milestone in the proximity of Olomouc, a well-known college town.

Father’s new responsibility did not overwhelm him for a moment, and he proved again that he could be trusted to handle effectively and proficiently any task that was assigned to him. And so, a couple of years later, he was promoted to District Manager of the Znojmo region. As a result, we had to move once again. But this time no one complained because we were moving closer to Kravsko and our grandparents.

As District Manager, father had two distinct areas of responsibilities. He had to manage the largest store in his District, the one located in the center of Znojmo, and at the same time supervise all the units in surrounding towns.

The large store faced Horni Zamesti, Znojmo’s major square. It was the only modern structure around the square, and with its four floors it was also one of the tallest. It had a flat roof and a large BATA sign prominently displayed at the very top of the building.

The entire first floor, bright and attractively appointed, was devoted to retail sales. It featured comfortable chairs, large displays and a concealed warehouse full of merchandise. The second floor held a large shoe-repair workshop on one side, and several pedicure booths on the other.

The third floor was reserved for single employees. It had several dorms and a large area for dining and social activities. The manager’s apartment occupied the complete fourth floor.

Our family had a maid because mother worked with father on the sales floor. She supervised the cash registers, and kept an eye on the entire business during father’s frequent trips into the district. The maid took care of us kids, cleaned the apartment and did some cooking. Occasionally, we were allowed to play with the toys displayed in the children’s section of the store (the company manufactured amazing toys, most of them molded in rubber). I spent long and happy hours in the company of all kinds of handsomely detailed toy soldiers and military hardware. The array included horse-drawn guns that were capable of firing rubber shells. And those shells easily toppled enemy troops, even at some distance (provided I aimed well, which was not always easy to do).Several of the soldiers held little electric bulbs that flashed Morse codes when activated by remote control. Let me assure you, I had great fun with all that military hardware.

I can truly say that we were good kids, and usually managed to stay out of serious trouble. But boys being boys, there were some exceptions to the rule. I remember the time when one of my innocent experiments went terribly wrong. I was playing on the roof, where we kept a couple of pet doves, when I decided to find out how fast an object would drop to the street after I released it from my towering vantage point. So, I chose a heavy hammer from my tool-box (I loved making things out of wood, and had a complete set of tools at my disposal) and threw it over the wall that ran around the perimeter of the roof. Fortunately, no one got hit with my missile. Unfortunately, the hammer bounced off the pavement and, for no good reason at all, decided to fly straight through one of the large and very expensive display-windows in the front of the store. That was the time that I receiving a good whipping from father.

The city of Znojmo is surrounded by a remarkable countryside. First there is the Dyie River that flows through one part of the town. Then there are lush forests, fertile fields, beautiful orchards, large vineyards and many recreational areas. We swam in the Dyje River (it was within walking distance from the store), and went on day trips into the nearby forests any time father was able to take off from his grueling schedule. We picked mushrooms and ran after butterflies whenever we emerged into meadows full of wild flowers. And when we stopped to rest, father liked to whittle twigs that he transformed, in no time at all, into whistles capable of producing clear, shrill sounds.

We also spent many happy times with our extended family in Kravsko, and enjoyed the company of our Viennese cousins, Susanne and Ruth, whenever their parents came down to visit. One summer season, Aunt Johanna rented an apartment in downtown Znojmo, and we actually became fond of having them constantly around, even though they were mere girls.

Visits with our family in Lostice were, as I mentioned earlier, quite infrequent. I guess that was because it took several hours to get there and father could not take too much time off from his responsibilities. Even on Sundays, when retail was closed, father regularly set up spot-checks of stores to find out whether any of them were having inventory shortages. Father worked seven days a week.

It was at the tender age of six years, during the 1936 school year, that I entered the first grade, and my days stopped being all fun and games.Still, it was not long before I adapted to the new routine, and to the new direction that my life was taking.

However, some time later, cracks started to appear in our peaceful universe, cracks that, in general, appeared insignificant. Yes, Europe’s crisis evolved slowly at first, but then its ominous rumblings took on the life of a runaway locomotive. There was no stopping the world from tumbling into an abyss.

Father saw the danger for what it was, and decided to save our lives by taking the family out of the country. Fortunately, the company had just started a program that gave its Jewish employees top priority for job-openings outside Czechoslovakia, and father jumped at the opportunity. And to move matters along, father requested an immediate transfer from the Retail Division to the Import/Export Division named Kotva (Czech name for anchor) because it was in the process of a vigorous expansion, and was opening new branches all over the world.

His request was approved in due time and, once again, new challenges were set in motion for our family. Father was assigned to a lesser job, one that allowed him to report regularly to Zlin, for Kotva’s orientation meetings on procedures and intricacies of the import/export business. He became the manager of a small store in Zidenice, a suburb of Brno.

We moved to Brno during the early part of 1938, an astounding city as far as I was concerned. The scope and cosmopolitan diversity surpassed anything else that I had experienced before. It was, and still is, the administrative and cultural capital of the Province of Moravia, and the second largest city in the country.

We had barely settled into our new home, when father was forced to leave for several weeks. It was not Zlin that required his presence that time. Being a reservist, he was recalled to temporary duty in the military. Czechoslovakia was determined to defend its borders against a potential german invasion.

I may be prejudiced, but father really was a dashing dragoon, and I have a picture to prove it. The photograph shows him in a standing position; he has a cap with a short visor on his head, a thin moustache on his upper lip and he is attired in a belted jacket, with a long sword clipped to the left side. He also holds a riding crop with his left hand, and a cigarette with the other. This is definitely a picture of the neatest cavalryman I had ever seen.

As I said before, Czechoslovakia mobilized because Hitler wanted to annex the Czech territory known as Sudeteland. It was ready to fight, even against the worst of odds, to prevent the break up of its territory and maintain its borders. It even formed alliances with France, England and other countries in the hope of safeguarding its independence. Unfortunately, nothing helped. In September of 1938, at the infamous meeting in Munich, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain surrendered to Hitler’s demands and sacrificed Czechoslovakia in the name of peace. Hitler had promised during the meeting that the Sudeteland would be his only territorial demands in Europe. But, as the World found out, this was just a ploy on his part. He grabbed the Sudeteland on September 19, 1938, and overran the rest of Czechoslovakia on March 14, 1939.

Fortunately for us, we managed to leave Czechoslovakia at the end of January, 1939, and narrowly escaped the Nazis by the skin of our teeth.

This is how it all came to pass.

After the reserve forces demobilized, and father returned home, he notified the office in Zlin that he wanted to get out of the country without further delays. He made it clear that he did not care where he would be transferred, as long as he could leave within weeks.

And so, as I mentioned at the beginning of this Memoir, the first position that became available was the one in Romania. Father “grabbed” it without hesitation, and arranged to have our travel documents processed on an emergency basis. At the same time, our parents started to grapple with another dilemma. They had to think about what to take along to our new destination, and what to leave behind. Eventually, practicality won over sentimentality, and they decided to leave most of our possessions in the good care of relatives. We were going to take only what we could fit in our personal luggage. After all, it was not as if we were leaving for good. A couple of years, at most, and we should be back home, reunited once more with those cherished possessions.

However, things did not work out as planned. To father’s dismay, the family passports were lost during visa processing at the Romanian Embassy and, by the time new ones were issued, the Romanian position had been given to some one else. Of course, this was really a blessing in disguise because Romania eventually became as unsafe as any other country in Europe.

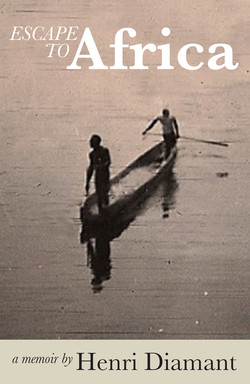

The very next opening that materialized was the one in the Congo, and that was how we landed in Elisabethville, the major town in Congo’s southeastern province of Katanga. Father’s assignment was to open the second Kotva branch in the colony. The first one, in the capital city of Leopoldville, was performing beyond all expectations, and the company wanted to cash in on that success.

Our new travel documents were issued during the month of December 1938, in a passport office right in downtown Zlin, By the way, this clearly shows the clout that Bata wielded with the Czech authorities. Think of it, in order to accommodate the company, the government maintained a passport office in Zlin, a private company town.

Father spent a couple of weeks in Zlin, for final briefings and for some general information about the Congo. However, once we reached our destination, it became obvious that the personnel in the export department had absolutely no clue about that particular area of the world. For instance, when father expressed his concerns about starting a brand new Kotva office in a strange country with a foreign language, he was told that there was nothing to worry about. To start with, the retail manager in Elizabethville had already been instructed to rent a good suite of offices for Kotva, and a suitable home for the family. Second, problems related to actual business could be worked out during frequent visits to Leopoldville. All father had to do was hop on the train once he closed the office on Friday evening, get all the advice he needed during an overnight stay in Leopoldville, and be home by opening time on Monday morning. Little did they know that there was no direct train connection between Elizabethville and Leopoldville, and that the round-trip journey would have taken father several weeks to accomplish. It is a rail and river route, where trains are used only to get around the non-navigable portions of the Congo River. Most of the trip is spent on paddle-wheel boats that sail cautiously over the ever-changing navigation channels during daylight hours, and drop anchor near riverbanks the minute it gets dark. This trek stretches for some 1500 miles.

By the way, in accordance with Congolese regulations, the company had to give father a three-year contract, so he could become eligible for work and residency permits in the colony. Another part of these rules required that, at the end of the three years, employees were given six-months of paid leave in a temperate-climate region (usually the employees’ country of origin), before resuming work in the tropics. This was deemed essential for the continued good health of employees and their dependents.

The immigration rules also required that we submit to thorough physical examinations, and be immunized against various tropical diseases. All of this took place over several days in the outpatient section of Zlin’s large hospital, and so we stayed at the company’s hotel for the duration of the procedures. It was not a lavish hotel, but it was thoroughly modern and exceptionally well run. It was regularly overrun with businessmen from all over the world.

In any event, we finally left on the first leg of our long journey at the end of January, 1939. We took the train from Prague to Antwerp, by way of Brussels. I remember Uncle Arnold standing on the quay and waving goodbye as we pulled out of Prague’s railroad terminal. Little did I realize at the time that it would be another thirteen years before I would see him again, this time in the USA, at the opposite side of the Atlantic Ocean. It was when Harry and I flew from the Congo to the States, early in 1952, to visit our relatives and to see for ourselves what that famous country was all about.

It was during that trip that I became totally captivated with the States, and decided right then and there that I would return, for good, the minute I could make it happen.

Anyway, after the train emerged from Prague’s cavernous depot and we eventually tired of gaping out of the window, we stowed our luggage in the overhead rack and made ourselves comfortable for the long journey. Harry and I played a board game while our parents remained unusually quiet, or so I thought, as the train rolled toward our first stop, the German border. They were evidently sad at leaving, but they must have been relieved that we were finally getting out of harm’s way.

Some time later, the train stopped across the border, right inside German territory, the country ruled by Hitler and his Nazi hordes. And yet, I do not remember experiencing any particular bouts of foreboding at the time, not even after what I saw next. The compartment door opened abruptly and a huge man, he must have been well over six feet tall, stepped boldly inside and instantly gave that hideous Nazi hand salute. He was dressed in an impeccable uniform, complete with the ugly swastika armband on his left sleeve and a side arm at his belt. Nonetheless, he was quite civil and actually processed our travel documents with professional courtesy. When he was done, he gave another Nazi hand salute, and firmly closed the compartment door on his way out. But, while the border crossing was uneventful for our family, others were not as fortunate. We heard that a number of passengers were not allowed to transit through Germany, and were forced to return to Czechoslovakia.

After changing trains in Brussels, we reached Antwerp on schedule, only to be told that our sailing date had been pushed back by a whole week because of some engine troubles on the vessel. This was unfortunate, not because we were reluctant to spend extra time in Antwerp, the center of Flemish culture for hundreds of years, but because father did not have much cash to pay for the unexpected layover (fiscal regulations had allowed only limited funds to be taken out of Czechoslovakia). Nonetheless, we managed to enjoy our extended time in Antwerp, even though we had to spend the week in a small and unassuming hotel, and had our meals at inexpensive restaurants. We saw the Cathedral of Our Lady, with its three monumental altarpieces painted by Peter Paul Rubens, the Grand Square (Grote Market) dominated by the Golden Age Town Hall and the Jewish neighborhood of Jootsewijk that was teeming with black-coated ultra orthodox jewish men.

Language was not much of a problem because many Flemish people understood enough German to communicate with our parents. By the way, three languages are spoken in Belgium; namely French (Walloon), Flemish and, to a much lesser degree, German. The latter is the regional language of a miniscule part of Belgium and does not wield the same influence as the other two languages. Both the Flemish and the French ethnic groups are extremely touchy about their heritage, and neither will tolerate discrimination in any form whatsoever. For instance, when the post office brings out new stamps, it has to make sure that half of each issue is printed with, for instance, “Belgique” on top of the design and “Belgie” underneath, while the other half of the issue has the names reversed the other way around. Both, French and Flemish are the two official languages of Belgium.

At last, our sailing date came, and we took a cab to the harbor and our liner, the SS Leopoldville. That turned out to be one of the most exciting days of my young life.

The date was February 13, 1939.

It was going to take me many years before I would walk once more on the European Continent.