Читать книгу The Violence of Organized Forgetting - Henry A. Giroux - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

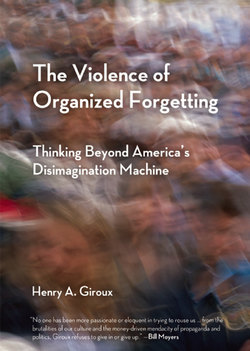

AMERICA’S DISIMAGINATION MACHINE

People who remember court madness through pain, the pain of the perpetually recurring death of their innocence; people who forget court another kind of madness, the madness of the denial of pain and the hatred of innocence.

—James Baldwin

America—a country in which forms of historical, political, and moral forgetting are not only willfully practiced, but celebrated—has become amnesiac. The United States has degenerated into a social order that views critical thought as both a liability and a threat. Not only is this obvious in the proliferation of a vapid culture of celebrity, but it is also present in the prevailing discourses and policies of a range of politicians and anti-public intellectuals who believe that the legacy of the Enlightenment needs to be reversed. Politicians such as Michelle Bachmann, Rick Santorum, and Newt Gingrich along with talking heads such as Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck, and Anne Coulter are not the problem. They are merely symptomatic of a much more disturbing assault on critical thought, if not rational thinking itself. The notion that education is central to producing a critically literate citizenry, which is indispensable to a democracy, is viewed in some conservative quarters as dangerous, if not treasonous. Under a neoliberal regime, the language of authority, power, and command is divorced from ethics, social responsibility, critical analysis, and social costs.

Today’s anti-public intellectuals are part of a disimagination machine that consolidates the power of the rich and supports the interconnected grid of military, surveillance, corporate, and academic structures by presenting the ideologies, institutions, and relations of the powerful as both commonsense and natural.1 For instance, the historical legacies of resistance to racism, militarism, privatization, and panoptical surveillance have long been forgotten in the current assumption that Americans now live in a democratic, post-racial society.2 The cheerleaders for neoliberalism work hard to normalize dominant institutions and relations of power through a vocabulary and public pedagogy that create market-driven subjects, modes of consciousness, and ways of understanding the world that promote accommodation, quietism, and passivity. As social protections and other foundations provided by the social contract come under attack and disappear, Americans are increasingly losing their capacity for connection, community, and a sense of civic engagement.

The Rise of the “Disimagination Machine”

Adapting Georges Didi-Huberman’s term “disimagination machine,” I argue that a politics of disimagination has emerged, in which stories, images, institutions, discourses, and other modes of representation are undermining our capacity to bear witness to a different and critical sense of remembering, agency, ethics, and collective resistance.3 The “disimagination machine” is both a set of cultural apparatuses—extending from schools and mainstream media to the new sites of screen culture—and a public pedagogy that functions primarily to short-circuit the ability of individuals to think critically, imagine the unimaginable, and engage in thoughtful and critical dialogue, or, put simply, to become critically engaged citizens of the world.

Examples of the “disimagination machine” abound. A few will suffice. For instance, the Texas State Board of Education and other conservative boards of education throughout the United States are rewriting American textbooks to promote and impose on America’s public school students what Katherine Stewart calls “a Christian nationalist version of U.S. history” in which Jesus is implored to “invade” public schools.4 In this version of history, the terms “human trafficking” and “slavery” are removed from textbooks and replaced with “Atlantic triangular trade;” Earth is merely 6,000 years old; and the Enlightenment is the enemy of education. Historical figures such as Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and Benjamin Franklin are now deemed to have suspect religious views and “are ruthlessly demoted or purged altogether from the study program.”5 Currently, 46 percent of the American population believes in the creationist view of evolution and increasingly rejects scientific evidence, research, and rationality as either “academic” or irreligious.6

The rise of the Tea Party and the renewal of culture wars have resulted in a Republican Party that is now considered the righteous party of anti-science.7 Similarly, right-wing politicians, media, talk show hosts, and other pundits loudly and widely spread the message that a culture of questioning is antithetical to the American way of life. Moreover, this message is also promoted by conservative groups such as the American Legislative Exchange Council, which “hit the ground running in 2013, pushing ‘model bills’ mandating the teaching of climate-change denial in public school systems.”8 Efforts to discredit climate change science are also promoted by powerful conservative groups such as the Heartland Institute. Ignorance is never too far from repression, as was demonstrated in Arizona when Representative Bob Thorpe, a Republican freshman Tea Party member, introduced a new bill requiring students to take a patriotic loyalty oath in order to receive a graduation diploma.9

The “disimagination machine”—though not entirely new to American culture—is more powerful than ever. Conservative think tanks provide ample funds for training and promoting anti-public pseudo-intellectuals and religious fundamentalists, while simultaneously offering policy statements and talking points to conservative media such as Fox News, Christian news networks, right-wing talk radio, and partisan social media and blogs. This ever-growing information-illiteracy bubble has become a powerful form of public pedagogy in the larger culture and is responsible not only for normalizing the war on science, reason, and critical thought, but also the war on women’s reproductive rights, communities of color, low-income families, immigrants, unions, public schools, and any other group or institution that challenges the anti-intellectual, antidemocratic world views of the new extremists. Liberal democrats, of course, contribute to this “disimagination machine” through educational policies that substitute forms of critical thinking and education for paralyzing pedagogies of memorization and rote learning tied to high-stakes testing in the service of creating a dumbed down and compliant work force. As the U.S. government retreats from its responsibility to foster the common good, it joins with corporate power to transform public schools into sites of containment and repression, while universities are “coming under pressure to turn themselves into training schools equipping young people with the skills required by the modern economy.”10 The hidden order of politics in this instance is that the United States has become an increasingly corporate space dominated not only by the script of cost-benefit analysis but also one in which creative powers of citizenship are being redefined as a narrow set of consumer choices.

What further keeps the American public in a state of intellectual servitude and fuels the hysteria of Judeo-Christian nationalism is the perception of being constantly under threat—a thinly veiled justification for ramping up state and corporate surveillance while extending the tentacles of the national security state.11 Through political messages filtered and spectacularized by the mass media, Americans have been increasingly encircled by a culture of fear and what Brad Evans has called “insecurity by design.”12 Americans are urged to adjust to survival mode, be resilient, and bear the weight of the times by themselves—all of which is code for a process of depoliticization.13 The catastrophes and social problems produced by the financial elite and mega-corporations now become the fodder of an individualized politics, a space of risk in which one can exhibit fortitude and a show of hypermasculine toughness. Or vulnerability is touted as a matter of common sense so as to mask the social, political, and economic forces that produce it, thus transforming it into an ideology whose purpose is to conceal power and encourage individuals to flee from any sense of social and political engagement. As Robin D. G. Kelley argues, “focusing on the personal obscures what is really at stake: ideas, ideology, the nature of change, the evisceration of our critical faculties under an appeal to neoliberal commonsense.”14

In this instance, the call to revel in risk and vulnerability as a site of identity formation and ontological condition makes invisible the oppressive workings of power. But it does more—it undermines any viable faith in the future and reduces progress to a script that furthers the neoliberal goals of austerity, privatization, and the accumulation of capital in the hands of the ruling and corporate elite. Meaningful social solidarities are torn apart and deterred, furthering a retreat into orbits of the private and undermining those spaces that nurture non-commodified knowledge, public values, critical exchange, and civic literacy. The pedagogy of authoritarianism is alive and well in the United States, and its repression of public memory takes place not only through the screen culture and institutional apparatuses of conformity, but also through a climate of fear and the ominous presence of a carceral state that imprisons more people than any other country in the world.15

The stalwart enemies of manufactured fear and militant punitiveness are critical thought and the willingness to question authority—as is abundantly evident, for example, in the case of Edward Snowden and those who champion him. What many commentators have missed in regard to Snowden is that his actions have gone beyond revealing merely how intrusive the U.S. government has become and have demonstrated how willing the state is to engage in vast crimes against the American public in the service of repressing dissent and a culture of questioning. Snowden’s real “crime” was that he demonstrated how knowledge can be used to empower the population to think and act as critically engaged communities fully capable of holding their government accountable. Snowden’s exposure of the massive reach of the surveillance state with its biosensors, scanners, face-recognition technologies, miniature drones, high-speed computers, massive data-mining capabilities, and other stealth technologies made visible “the stark realities of disappearing privacy and diminishing liberties.”16 Making the workings of oppressive power visible has its costs, and Snowden has become a flashpoint revealing the willingness of the state to repress dissent regardless of how egregious such a practice might be.

Since the late 1970s, there has been an intensification in the United States, Canada, and Europe of neoliberal modes of governance, ideology, and policies—a historical period in which the foundations for democratic public spheres have been dismantled.17 Schools, libraries, the airwaves, public parks and plazas, and other manifestations of the public sphere have been under siege, viewed as disadvantageous to a market-driven society that considers noncommercial imagination, critical thought, dialogue, and civic engagement a threat to its hierarchy of authoritarian operating systems, ideologies, and structures of power, domination, and control. The 1970s marked the beginning of a historical era in which the discourses of democracy, public values, and the common good came crashing to the ground. First Margaret Thatcher in Britain and then Ronald Reagan in the United States—both hard-line advocates of market fundamentalism—announced that there was no such thing as society and that government was the problem, not the solution. Democracy and the political process were all but sacrificed to the power of corporations and the emerging financial service industries, just as hope was appropriated as an advertisement for a whitewashed world in which the function of culture to counter oppressive social practices was greatly diminished.18 Large social movements fragmented into isolated pockets of resistance mostly organized around a form of identity politics that largely ignored a much-needed conversation about the attack on the social and the broader issues affecting society, such as increasingly harmful disparities in wealth, power, and income. Tony Judt argues this point persuasively in his insistence that politics

devolved into an aggregation of individual claims upon society and the state. “Identity” began to colonize public discourse: private identity, sexual identity, cultural identity. From here it was but a short step to the fragmentation of radical politics, its metamorphosis into multiculturalism. . . . However legitimate the claims of individuals and the importance of their rights, emphasizing these carries an unavoidable cost: the decline of a shared sense of purpose. Once upon a time one looked to society—or class, or community—for one’s normative vocabulary: what was good for everyone was by definition good for anyone. But the converse does not hold. What is good for one person may or may not be of value or interest to another. Conservative philosophers of an earlier age understood this well, which was why they resorted to religious language and imagery to justify traditional authority and its claims upon each individual.19

As forms of state sovereignty gave way to market-centered private modes of political control, the United States morphed into an increasingly authoritarian space in which young people became the most visible symbol of the collateral damage that resulted from the emergence, especially after 9/11, of a new kind of domestic terrorism. If the enemy abroad was defined as the Islamic other, young people increasingly obtained the status of the enemy at home, especially youthful protesters and young people of color. Neoliberalism’s war on youth is significant as both a war on the future and on democracy itself. Youth are no longer the place where society reveals its dreams. Instead, youth are becoming the site of society’s nightmares. Within neoliberal narratives, youth are defined opportunistically in terms of contradictory symbols, whether as a consumer market, a drain on the economy, or as an intransigent menace.20

Young people increasingly have become subject to an oppressive disciplinary system that teaches them to understand citizenship through the pecuniary practices of the market and to follow orders and toe the line in the face of authority, no matter how counterintuitive, unpleasant, or oppressive doing so may be. They are caught in a society in which almost every aspect of their lives is shaped by the dual forces of the market and a growing police state. The message is clear: get in on buying/selling or be ignored or punished. Mostly out of step, young people, especially people of color and low-income whites, are inscribed within a machinery of dead knowledge, social relations, and values in which there is an attempt to render them voiceless and invisible. Often relegated to sites of terminal exclusion, many young people are forced to negotiate their fates alone, bearing full responsibility for a society that forces them to bear the weight of problems that are not of their own making and for which they bear no personal blame. For example, what prospects are waiting for teenagers who age out of the foster care system at eighteen years old and go out into our minimum-wage society on their own? What future do they have? For many, the answer is military recruitment or prison. What is particularly new is the way in which young people have been increasingly denied a significant place in an already weakened social contract and the degree to which they are absent from how many countries’ leaders now envision the future.21

How young people are represented betrays a great deal about the economic, social, cultural, and political constitution of American society and its growing disinvestment in young people, the social state, and democracy itself.22 The structures of neoliberal violence have diminished the vocabulary of democracy, and one consequence is that subjectivity and education are no longer the lifelines of critical forms of individual and social agency. This is most evident in the attack on public schools in the United States, an attack that is as vicious as it is authoritarian. The war on schools by billionaires such as Bill Gates (Microsoft) and the Walton family (Walmart), among others, is attempting to corporatize classroom teaching by draining pedagogy of any of its critical functions while emphasizing “teaching to the test.” Similarly, schools are being reorganized so as to eliminate the influence of unions and the power of teachers. As Michael Yates points out, they have begun “to resemble assembly lines, with students as outputs and teachers as assembly-line-like mechanisms who do not think or instill in their students the capacity to conceptualize critically and become active participants in a democratic society.”23 Such schools have become punishing factories waging a war on the radical imagination and undermining those rationalities where desire is constructed and behavior specified that embraces civic courage and the common good.

The promises of modernity regarding progress, freedom, and hope as part of the project of extending and deepening the ideals of democracy have not been eliminated; they have been reconfigured, stripped of their emancipatory potential and relegated to the logic of a savage market instrumentality. Modernity has reneged on its promise to young people to provide them with social mobility, economic well-being, and collective security. Long-term planning and the institutional structures that support it are now fully subservient to the financial imperatives of privatization, deregulation, commodification, flexibility, and short-term profits. Social bonds have fragmented as a result of the attack on the welfare state and the collapse of social protections. Moreover, all possible answers to socially produced problems are now limited to the mantra of individual, market-based solutions.24 It gets worse. Increasingly, those individuals and groups who question the savage logic of the free market or are unable to function within it as atomized employees/consumers are viewed contemptuously as either traitors or moochers and are rendered disposable by corporate and government elites.25

Public problems now collapse into the limited and depoliticized register of private issues. Individual self-interest now trumps any consideration of the good society just as all problems are ultimately laid at the door of the solitary individual whose fate is shaped by forces far beyond his or her personal control. Under neoliberalism, everyone has to negotiate their fate alone, bearing full responsibility for problems that are often not of their own doing. The implications politically, economically, and socially for young people are disastrous and are contributing to the emergence of a generation that will populate a space of social abandonment and terminal exclusion. Job insecurity, debt servitude, impoverishment, enlistment to war zones, incarceration, and a growing network of real and symbolic violence have dismissed too many young people to a future that portends zero opportunities and zero hope. This is a generation that has become a primary target for disposability through prison or war, consignment to debt, and new levels of surveillance and consumer control.

The severity and consequences of this shift for youth are evident in the fact that this will be the first generation in which the “plight of the outcast may stretch to embrace a whole generation.”26 Zygmunt Bauman argues that today’s youth have been “cast in a condition of liminal drift, with no way of knowing whether it is transitory or permanent.”27 That is, the generation of youth in the early twenty-first century has no way of grasping if it will ever “be free from the gnawing sense of the transience, indefiniteness, and provisional nature of any settlement.”28 Neoliberal violence—originating in part from a massive accumulation of wealth by the elite 1 percent of society, growing inequality, the reign of the financial service industries, the closing down of educational opportunities, and the stripping of social protections from those marginalized by race and class—has produced an entire generation without jobs, an independent life, and even the most minimal social benefits.

Youth no longer inhabit the privileged space, however compromised, that was offered to previous generations. They now move listlessly through a neoliberal notion of temporality as dead time, devoid of faith in progress and entranced by a belief in those apocalyptic narratives in which the future appears indeterminate, bleak, and insecure. Progressive visions pale and recede next to the normalization of wealth-driven policies that wipe out pensions, punish unions, demonize public servants, raise college tuition, and produce a harsh world of joblessness—all the while giving billions of dollars and “huge bonuses, instead of prison sentences . . . to those bankers and investment brokers who were responsible for the 2008 meltdown of the economy and the loss of homes for millions of Americans.”29 Students, in particular, now find themselves in a world in which heightened expectations have been replaced by dashed hopes. The promises of higher education and previously enviable credentials have turned into their opposite: “For the first time in living memory, the whole class of graduates faces a future of crushing debt, and a high probability, almost the certainty, of ad hoc, temporary, insecure and part-time work and unpaid ‘trainee’ pseudo-jobs deceitfully rebranded as ‘practices’—all considerably below the skills they have acquired and eons below the level of their expectations.”30

What has changed for an entire generation of young people includes not only neoliberal society’s disinvestment in youth and the lasting fate of downward mobility, but also the fact that youth live in a commercially saturated and commodified environment that is unlike anything previously imposed. Nothing has prepared this generation for the inhospitable and savage new world of commodification, privatization, joblessness, frustrated hopes, and stillborn projects.31 Advertising provides the primary imagery for their dreams, relations to others, identities, and sense of agency. There appears to be no space outside the panopticon of commercial debasement and casino capitalism. The present generation has been born into a throwaway world of consumption and control in which both goods and people are increasingly viewed as entirely disposable. Young people now reside in a world in which there remain few public spheres or social spaces beyond the controlling influence of the market, the warfare state, debtfare, and sprawling tentacles of the NSA and its national surveillance apparatus.

The structures of neoliberal modernity do more than disinvest from young people: they also transform the protected space of childhood into a zone of disciplinary exclusion and cruelty, especially for those families who are marginalized by race, class, and residency status and who are forced to occupy a social landscape in which they are increasingly disparaged as flawed consumers or pathologized others. With no adequate role to play as owners and consumers, many youth are now considered disposable, forced to inhabit “zones of social abandonment” extending from homeless shelters and impoverished schools to bulging detention centers and prisons. 32 In the midst of the rise of the punishing state, the circuits of state repression, surveillance, and disposability “link the fate of blacks, Latinos, Native Americans, poor whites, and Asian Americans” who are caught in a governing-through-crime youth complex that essentially serves as a default solution to major social problems.33 As Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri point out, young people live in a society in which every institution becomes an “inspection regime”—recording, watching, gathering information and storing data.34 Complementing these regimes is the shadow of the prison which is no longer separated from society as an institution of total surveillance. Instead, “total surveillance is increasingly the general condition of society as a whole. “The prison,” Michel Foucault notes, “begins well before its doors. It begins as soon as you leave your house—and even before.”35

Everyone Is Now a Potential Terrorist

Today young people all over the world are building movements against a variety of grievances ranging from economic injustice and massive inequality to drastic cuts in education and public services. These social networks have and currently are being met with state-sanctioned violence and an almost pathological refusal to respond to the articulation of social needs and demands. In the United States, the state monopoly on the use of violence has intensified since the 1980s, and in the process has been increasingly directed against youth, low-income populations, communities of color, people with disputed residency status, and women. As the welfare state is hollowed out, a culture of compassion is replaced by a culture of violence and cruelty. Collective insurance policies and social protections have given way to the forces of corporate predation, the transformation of the welfare state into punitive workfare programs, the privatization of public goods, and an appeal to individual competition and ambition as a substitute for civic agency and community engagement.

Under the notion that unregulated market-driven values and relations should shape every domain of human life, the business model of governance has eviscerated any viable notion of social responsibility while furthering the criminalization of social problems and cutbacks in basic social services, especially for young people, the elderly, people of color, and the impoverished.36 At this historical juncture there is a merging of violence and governance along with the systemic disinvestment in and breakdown of institutions and public spheres that have provided the minimal conditions for democracy. This becomes obvious in the emergence of a surveillance state in which social media not only become new platforms for the invasion of privacy but further legitimate a culture in which monitoring functions are viewed as both necessary and benign. Meanwhile, the state-sponsored society of hyper-fear increasingly regards each and every person as a potential terrorist suspect.

The war on terrorism has increasingly morphed into a war on dissent. As Kate Epstein argues, one “very real purpose of the surveillance programs—and perhaps the entire war on terror—is to target and repress political dissent. ‘Terrorism’ is the new ‘Communism,’ and the war on terror and all its shiny new surveillance technology is the new Cold War and McCarthyism.”37 Everyone, especially people in communities of color, now adjusts to a panoptical existence in which “living under constant surveillance means living as criminals.”38 As young people make diverse claims on the promise of a renewed democracy, articulating what a fair and just world might be, they are increasingly met with forms of physical, ideological, and structural violence. Abandoned by the existing political system, young people in Oakland, New York City, Montreal, and numerous other cities throughout the globe have placed their bodies on the line, protesting peacefully while trying to develop new organizations for democracy, to imagine long-term institutions, and to support notions of “community that manifest the values of equality and mutual respect that they see missing in a world that is structured by neoliberal principles.”39 In Quebec, despite police violence and threats, thousands of students demonstrated for months against a former right-wing government that wanted to raise tuition and cut social protections. Such demonstrations against the language and politics of austerity have taken place in a variety of countries throughout the world and embrace a new understanding of the commons as a shared space of participatory knowledge, enrichment, debate, and exchange.

These movements are thinking beyond a financialized notion of exchange based exclusively on notions of buying and selling. They are not simply about addressing current injustices and reclaiming space, but also about reawakening the social imagination, acting on new ideas, advancing new conversations, and embodying a new political language. Rejecting the corporate line that democracy and markets are the same, young people are calling for an end to the normalization of chronic impoverishment, accelerating economic inequality, the suppression of dissent, and the permanent war state. Today’s movement-building youth refuse to be acknowledged exclusively as consumers or to accept that the only interests that matter are fiscal. These creative young people and the movements they are advancing are raising a diverse range of voices in opposition to market-driven values and practices that aim at both limiting agency to civic community and undermining those public spheres that create networks of solidarity and reinforce a commitment to the common good.

Resistance and the Politics of the Historical Conjuncture

Marginalized youth, workers, artists, and others are raising serious questions about the violence of inequality and the authoritarian hierarchies that legitimate it. They are calling for a redistribution of wealth and power—not within the old system but in a new one in which democracy becomes more than a slogan or a legitimation for authoritarianism and state violence. As Angela Y. Davis and Stanley Aronowitz, among others, have argued, the fight for education and justice is inseparable from the struggle for economic equality, human dignity, and security, and the challenge of developing American institutions along genuinely democratic lines. Today, there is a new focus on public values, the need for broad-based movements, and imagining viable systems for securing democracy, social justice, and ecological sustainability. And while the visibility of youth protests have waned, many young people are working locally to forge a deeper notion of justice, one in which appeals to justice are matched by effort to change the dominant ideologies and structural relations that inform everyday life.

All of these issues are important, but what must be addressed in the most immediate sense is the threat posed by the emerging surveillance state in the United States. Beyond targeting the activists of all ages who are rising up in a number of American cities, the militarization of society poses a clear threat to democracy itself. This threat is being exacerbated as a result of the merging of a warlike mentality and neoliberal modes of discipline and education in which it becomes difficult to reclaim the language of conscience, social responsibility, and civic engagement.40 Everywhere we look we see the encroaching shadow of the national surveillance state. The government now requisitions personal telephone records and sifts through private emails. It labels whistle-blowers, such as Edward Snowden, traitors, even though they have exposed the corruption and lawlessness practiced on an ongoing basis by elite authorities who operate above and beyond the laws to which the rest of the population are subjected. While state authorities spy on the general population and bankers commit acts of economic mass destruction with virtual impunity, ordinary Americans go to jail by the thousands simply for protesting. For example, in a 24-month period, more than 7,000 people went to jail for participating in protests associated with the Occupy movement.41 The U.S currently imprisons over 2.3 million human beings while “6 million people at any one time [are] under carceral supervision—more than were in Stalin’s Gulag.”42

While little national attention is given to the thousands of arrests and acts of violence that were waged against the Occupy movement and other protesters, it is important to situate such state aggression within a broader set of categories that not only enables a better understanding of the underlying social, economic, and political forces at work in such assaults, but also allows us to reflect critically on the distinctiveness of the current historical period in which such repression of democracy is taking place. For example, it is difficult to address state-sponsored violence against free speech and protest without analyzing the devolution of the social state and the corresponding rise of the warfare and punishing state.

Stuart Hall’s reworking of Gramsci’s notion of conjuncture is important here because it provides both a conceptual opening into the forces shaping a particular historical moment and a framework for merging theory and strategy.43 Conjuncture in this case refers to a period in which different elements of society come together to produce a unique fusion of the economic, social, political, ideological, and cultural in a relative settlement that becomes hegemonic in defining reality. That fusion is today marked by a neoliberal conjuncture. In this particular historical moment, the notion of conjuncture helps us to address theoretically how state surveillance and repression of free speech and widespread nonviolent protests are largely related to a historically specific neoliberal project that advances vast inequalities in income and wealth, creates the student loan debt bomb, eliminates much-needed social programs, eviscerates the social wage, and privileges profit over people. Youth today live in a period of history marked by an “epochal crisis” in which they are largely considered disposable, relegated to the savage dictates of a survival-of-the fittest society in which they are now considered on their own and governed by a generalized fear of being unemployed or not being able to survive.44

Within the United States especially, the often violent response to nonviolent forms of social protest must also be analyzed within the framework of a mammoth military-industrial state and its commitment to war and the militarization of the entire society.45 The merging of the military-industrial complex, the surveillance state, and unbridled corporate power points to the need for strategies that address what is specific about the current neoliberal warfare state and how different interests, modes of power, social relations, public pedagogies, and economic configurations come together to shape its politics. Thinking in terms of such a conjuncture is invaluable politically in that it provides a theoretical opening for making the practices of the warfare state and the neoliberal revolution visible in order “to give the resistance to its onward march content, focus, and a cutting edge.”46 It also points to the conceptual power of making clear that history remains an open horizon that cannot be dismissed through appeals to the end of history or end of ideology.47 It is precisely through the indeterminate nature of history that resistance becomes possible and politics refuses any guarantees and remains open.

I want to argue that the current historical moment or what Stuart Hall called the “long march of the Neoliberal Revolution” is best understood in terms of the growing forms of violence that it deploys and reinforces.48 Such antidemocratic pressures and their relationship to protests in the United States and abroad are evident in the crisis that has emerged through the integration of governance and violence, the growth of the punishing state, and the persistent development of what has been described by Alex Honneth as “a failed sociality.”49 The United States has become addicted to violence, and this dependency is fueled increasingly by its willingness to wage war at home and abroad.

War in this instance is not merely the outgrowth of policies designed to protect the security and well-being of the United States. It is also, as C. Wright Mills pointed out, part of a “military metaphysics”—a complex of forces that includes corporations, defense industries, politicians, financial institutions, and universities.50 War provides jobs, profits, political payoffs, research funds, and forms of political and economic power that reach into every aspect of society. Waging war is also one of the nation’s most honored virtues, and its militaristic values now bear down on almost every aspect of American life.51 As modern society is increasingly defined by the realities of permanent war, a carceral state, and a national surveillance infrastructure, the social stature of the military and soldiers has risen.52 As Michael Hardt and Tony Negri point out: “In the United States, rising esteem for the military in uniform corresponds to the growing militarization of the society as a whole. All of this despite repeated revelations of the illegality and immorality of the military’s own incarceration systems, from Guantánamo to Abu Ghraib, whose systematic practices border on if not actually constitute torture.”53 The state of exception in the United States, in particular, has become permanent and promises no end. War has become a mode of sovereignty and rule, eroding the distinctions between war and peace, defense and provocation. Increasingly fed by a coordinated moral and political hysteria, warlike values produce and endorse shared fears as the primary register of social relations.

The war on terror, rebranded under Obama as the “Overseas Contingency Operation,” has morphed into a war on democracy. Everyone is now considered a potential terrorist, providing a rationale for both the government and private corporations to spy on anybody, regardless of whether they have yet to be suspected of a crime. Surveillance is supplemented by increasingly militarized police forces that now receive intelligence, weapons, and training from federal authorities like the Department of Homeland Security. Military technologies such as drones, SWAT vehicles, and machine-gun-equipped armored trucks once used exclusively in combat zones such as Iraq and Afghanistan are now being supplied to local police departments across the nation, and not surprisingly “the increase in such weapons is matched by training local police in war zone tactics and strategies.”54

The domestic war against “terrorists” [increasingly a code for those who dare to protest] provides new opportunities for major defense contractors and corporations who “are becoming more a part of our domestic lives.”55 As Glenn Greenwald points out, “Arming domestic police forces with para-military weaponry will ensure their systematic use even in the absence of a terrorist attack on U.S. soil; they will simply find other, increasingly permissive uses for those weapons.”56

Of course, the new domestic paramilitary forces will also undermine free speech and dissent with the threat of force while simultaneously threatening core civil liberties, human rights, and civic responsibilities. Given that “by age 23, almost a third of Americans are arrested for a crime,” it becomes clear that in the new militarized state young people, especially those in communities of color, are viewed as predators and treated as either a threat to corporate governance or a disposable population.57 This siege mentality will only be reinforced by the collaboration of the state with private intelligence and surveillance agencies; the violence such an alliance produces will increase, as will the growth of a punishment state that acts with impunity. Scholars like Michelle Alexander demonstrate that this contemporary violence is in many ways an extension of the state’s application of Jim Crow laws, which themselves extended from the generations of domestic terror that white enslavers institutionalized to control people they had bought, bred, and sold for profit.58

Yet there is more at work here than the prevalence of armed knowledge and a militarized discourse: there is also the emergence of a militarized society that now organizes itself “for the production of violence.”59 America has become a society in which “the range of acceptable opinion inevitably shrinks.”60 War has become normalized and no longer needs to be declared. The targets of war increasingly expand from communities of color and immigrants to youth, low-income women, and unions. War is no longer aimed at restoring peace but sacrificing it, along with any hope for a different future. The endless updating of a machinery of warfare and death has not just become permanent, it has become a booming growth industry. The normalization of permanent war does more than promote a set of unifying symbols that embrace a survival-of-the-fittest ethic, favoring conformity over dissent, the strong over the weak, and fear over responsibility. It also gives rise to what David Graeber has called a “language of command” in which violence becomes the most important element of power and a mediating force in shaping most, if not all, social relationships.61

Permanent War and the Public Pedagogy of Acceptable Ambient Violence

A permanent war state inevitably relies on modes of public pedagogy that influence willing subjects to abide by its values, ideology, and narratives of fear and violence. Such legitimation in the United States today is largely provided through a market-driven system addicted to the production of consumerism, militarism, and organized violence that circulates through various registers of commercial culture extending from television shows and Hollywood movies to violent video games and music concerts sponsored by the Pentagon. The market-driven spectacle of war demands a culture of compliance: silenced intellectuals and a fully entertained population distracted from the living nightmare of correctable injustices all around them. There is also a need for subjects who can be shaped to derive pleasure in the commodification of violence and a culture of cruelty. Under neoliberalism, culture appears to have largely abandoned its role as a site of critique. Very little appears to escape the infantilizing influence and moral vacuity of those who run the market. Film, television, video games, children’s toys, cartoons, and even high fashion are all shaped to normalize a society centered on war and violence. For instance, in 2013, following disclosure of NSA and PRISM spying revelations, the New York Times ran a story on a new line of fashion with the byline: “Stealth Wear Aims to Make a Tech Statement.”62

As the pleasure principle becomes less constrained by a moral compass based on a respect for others, it is increasingly shaped by the need for intense excitement and a never-ending flood of heightened sensations. Advanced by commercialized notions of aggression and cruelty, a culture of violence has become commonplace in a social order in which pain, humiliation, and abuse are condensed into digestible spectacles endlessly circulated through new and old forms of media and entertainment. But the ideology and the economy of pleasure it justifies are also present in the material relations of power that have intensified since the Reagan presidency, when a shift in government policies first took place and set the stage for the contemporary reemergence of unchecked torture and state violence under the Bush-Cheney regime. Conservative and liberal politicians alike now spend millions waging wars around the globe, funding the largest military state in the world, providing huge tax benefits to the ultra-rich and major corporations, and all the while draining public coffers, increasing the scale of human poverty and misery, and eliminating all viable public spheres—whether they be the social state, public schools, public transportation, or any other aspect of a democratic culture that addresses the needs of the common good.

State violence—particularly the use of torture, abductions, and targeted assassinations—is now justified as part of a state of exception in which a “political culture of hyper-punitiveness” has become normalized.63 Revealing itself in a blatant display of unbridled arrogance and power, it appears unchecked by any sense of conscience or morality. How else to explain right-wing billionaire Charles Koch insisting that the best way to help the poor is to get rid of the minimum wage? In response, journalist Rod Bastanmehr pointed out that “Koch didn’t acknowledge the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots, but he did make sure to show off his fun new roll of $100-bill toilet paper, which was a real treat for folks everywhere.”64 It gets worse. Ray Canterbury, a Republican member of the West Virginia House of Delegates, insisted that “students could be forced into labor in exchange for food.”65 In other words, students could clean toilets, do janitorial work, or other menial chores in order to pay for their free school breakfast and lunch programs. In Maine, Republican Representative Bruce Bickford has argued that the state should do away with child labor laws. His rationale speaks for itself. He writes: “Kids have parents. Let the parents be responsible for the kids. It’s not up to the government to regulate everybody’s life and lifestyle. Take the government away. Let the parents take care of their kids.”66 This is a version of Social Darwinism on steroids, a tribute to Ayn Rand that would make even her blush.

Public values are not only under attack in the United States and elsewhere they appear to have become irrelevant. Those spaces that once enabled an experience of the common good are now disdained by right-wing and liberal politicians, anti-public intellectuals, and an army of media pundits. State violence operating under the guise of increasing personal safety and security, while parading as a bulwark of democracy, actually does the opposite and cancels out democracy “as the incommensurable sharing of existence that makes the political possible.”67 Symptoms of ethical, political, and economic impoverishment are all around us. One recent example can be found in the farm bill passed by Republicans, which provides $195 billion in subsidies for agribusiness, while slashing roughly $8 billion from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). SNAP provides food stamps for people living below the poverty line. Not only are millions of food stamp beneficiaries still at risk for malnourishment and starvation, it is estimated that benefits would be entirely eliminated for nearly two million Americans, many of them children. Katrina vanden Heuvel writes in the Washington Post that it is hard to believe that any party would want to publicize such cruel practices. She states:

In this time of mass unemployment, 47 million Americans rely on food stamps. Nearly one-half are children under 18; nearly 10 percent are impoverished seniors. The recipients are largely white, female and young. The Republican caucus has decided to drop them from the bill as “extraneous,” without having separate legislation to sustain them. Who would want to advertise these cruel values?68

Neoliberal policies have produced proliferating zones of precarity and exclusion that are enveloping more and more individuals and groups who lack jobs, need social assistance and health care, or are homeless. According to the apostles of modern-day capitalism, providing “nutritional aid to millions of pregnant mothers, infants, and children . . . feeding poor children, and giving them adequate health care” is a bad expenditure because it creates “a culture of dependency—and that culture of dependency, not runaway bankers, somehow caused our economic crisis.”69 What is left out of the spurious and cruel assertion that social provisions create a culture of dependency, especially with respect to the food stamp program, is that “six million Americans receiving food stamps report they have no other income. [Many describe] themselves as unemployed and receiving no cash aid—no welfare, no unemployment insurance, and no pensions, child support or disability pay. . . . About one in 50 Americans now lives in a household with a reported income that consists of nothing but a food-stamp card.”70 Needless to say, there is more to the culture of cruelty than ethically challenged policies that benefit the rich and punish the poor, particularly children. There is also the emergence of a carceral state that operates a governing-through-crime youth complex and a school-to-prison pipeline that essentially functions as a new extension of Jim Crow.71

The strengthening of the school-to-prison pipeline—seen in the increased acceptance of criminalizing the behavior of young people in public schools—is a grotesque symptom of the way in which violence has saturated everyday life. Behaviors that were normally handled by teachers, guidance counselors, and school administrators are now dealt with by the police and the criminal justice system. Under such circumstances, not only do schools resemble the culture of prisons, but young children are being arrested and subjected to court appearances for behaviors that can only be termed as trivial. How else to explain the case of a diabetic student who, because she fell asleep in study hall, was arrested and beaten by the police or the arrest of a seven-year-old boy who, because of a fight he got into with another boy in the schoolyard, was put in handcuffs and held in custody for ten hours in a Bronx police station?72 In Texas, students who miss school are not sent to the principal’s office or assigned detention. Instead, they are fined and in too many cases actually jailed.73 It is hard to imagine, but in a Maryland school, a thirteen-year-old girl was arrested for refusing to say the pledge of allegiance.74 In these examples, we see more at work than stupidity and a flight from responsibility on the part of educators, parents, and politicians who maintain these laws. We see actions motivated by an underlying belief and growing sentiment that young people constitute a threat to adults and that the only way to deal with them is to subject them to mind-crushing punishment.

The consequences have been disastrous for many young people. Even more disturbing is how the legacy of slavery informs these practices, given that “arrests and police interactions . . . disproportionately affect low-income schools with large African-American and Latino populations.”75 Instead of schools being a pipeline to opportunity, low-income white youth and children of color are being funneled directly from schools into prisons. Feeding the expanding prison-industrial complex, justified by the war on drugs, the United States is in the midst of a prison binge made obvious by the fact that “since 1970, the number of people behind bars . . . has increased 600 percent.”76 It is estimated that in some cities, such as Washington D.C., 75 percent of young black men can expect to serve time in prison. Michelle Alexander has pointed out that “one in three young African American men is currently under the control of the criminal justice system—in prison, in jail, on probation, or on parole—yet mass incarceration tends to be categorized as a criminal justice issue as opposed to a racial justice or civil rights issue (or crisis).”77

Young people of color in America have an ascribed identity that is a direct legacy of the society created by generations of white enslavers. Black men are particularly considered threatening, expendable, and part of a culture of criminality. They are deemed guilty of criminal behavior not because of the alleged crimes they might commit, but because a collective imagination paralyzed by the racism of a white supremacist culture that can only view them as a disturbing threat. Clearly, the real threat resides in a social order that hides behind the mutually informing and poisonous notions of colorblindness and a post-racial society, a convenient rhetorical obfuscation that allows white Americans to ignore the institutional and individual ideologies, practices, and policies that support toxic forms of racism and destroy any viable notions of justice and democracy. As the Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis cases made clear, when young black men are not being arrested and channeled into the criminal justice system in record numbers, they are being targeted by vigilantes and private security forces and in some instances killed because they are black and assumed to be dangerous—or in Davis’s case because he was playing loud rap music.78 This medieval type of punishment inflicts pain on both the psyches and bodies of young people as part of a public spectacle of domination and subordination.

Anyone belonging to a population identified and treated as disposable faces an existence in which the ravages of segregation, racism, poverty, and dashed hopes are amplified by the forces of “privatization, financialization, militarization, and criminalization,” fashioning a new architecture of punishment, massive human suffering, and authoritarianism.79 Students being miseducated, criminalized, and arrested through a form of penal pedagogy in prison-type schools provide a grim reminder of the degree to which the ethos of containment and punishment now creeps into spheres of everyday life that were largely immune in the past from this type of state violence. This is not merely barbarism parading as reform—it is also a blatant indicator of the degree to which sadism and the infatuation with violence have become normalized in a society that seems to take delight in dehumanizing most of its population.

Widespread violence now functions as part of an antiimmune system that turns the economy of sadistic pleasure into the foundation for sapping democracy of any political substance and moral vitality. Democracy in the United States is increasingly battered by a collusion between financial elites and a surveillance state that de-prioritizes their “complex” crimes of economic mass destruction.80 An American disimagination machine producing civic death and historical amnesia penetrates into all aspects of national life, suggesting that all who are marginalized by class, race, and ethnicity have been permanently abandoned. But historical and public memory are not merely on the side of those enforcing domination.

Anthropologist David Price asserts that historical memory can be a source of renewal within the “desert of organized forgetting” and suggests a rethinking of the role that artists, intellectuals, educators, youth, and other concerned citizens can play in fostering a “reawakening America’s battered public memories.”81Against the tyranny of forgetting, educators, young people, social activists, public intellectuals, workers and others can make visible and oppose the long legacy and current reality of state violence and the rise of the punishing state. Such a struggle suggests not only reclaiming, for instance, education as a public good but also reforming the criminal justice system and removing police from schools. In addition, there is a need to employ public memory, critical theory, and other intellectual archives and resources to expose the crimes of those market-driven criminogenic regimes of power that now run the commanding institutions of society and that have transformed the welfare state into a warfare state.

The consolidation of capitalism, counterintelligence, and the carceral state with their vast apparatuses of real and symbolic violence must also be situated and understood as part of a broader historical and political attack on public values, civic literacy, activism, and social justice. Crucial here is the need to engage how such an attack is aided and abetted by the emergence of a poisonous neoliberal public pedagogy that depoliticizes as much as it entertains and corrupts. State violence cannot be defined as simply a political issue. Also operating in tandem with politics are pedagogical forces that wage violence against the minds, desires, bodies, and identities of young people as part of the reconfiguration of the social state into the punishing state. At the heart of this transformation is the emergence of a new form of corporate sovereignty, a more intense form of state violence, a ruthless survival-of-the-fittest ethic used to legitimate the concentrated power of the rich, and a concerted effort to punish young people who are out of step with official lists, ideology, values, and modes of social control.

Making young people bear the burden of a severe educational deficit has enormous currency in a society in which existing relations of power are normalized. Under such conditions, those who hold power accountable are viewed as treasonous while critically engaged young people are denounced as un-American.82 In any totalitarian society, dissent is a threat, civic literacy is denounced, and those public spheres that produce engaged citizens are dismantled or impoverished through the substitution of genuine education with job training. Edward Snowden, for one, was denounced as being part of a generation that combined being educated with a distrust of authority. It is important to note that Snowden was labeled as a spy, not a whistle-blower—even though he exposed the reach of the spy services into the lives of most Americans. Of course, these antidemocratic tendencies represent more than a threat to young people: they also put in peril all of those communities, individuals, groups, public spheres, and institutions now considered disposable because they are at odds with a world run by bankers and the financial elite. Only a well-organized movement of young people, educators, workers, parents, religious groups, and other concerned citizens will be capable of changing the power relations and vast economic inequalities responsible for turning the United States into a country in which it is almost impossible to recognize the ideals of a real democracy.

Learning to Remember

The rise of America’s disimagination machine and its current governing-through-punishment operating system suggest the need for a politics that not only negates the established order but imagines a new one, one informed by a radical vision in which the future does not imitate the present.83 Learning to remember means merging a critique of the way things are with a sense of realistic hope or what I call educated hope, and transforming individual memories and struggles into collective narratives and larger social movements. The resistance that young people are mobilizing against oppressive societies all over the globe is being met with state-sponsored violence that is about more than militant police brutality. This is especially clear in the United States, where the shift from social welfare to a constant warfare state has replaced a culture of civic responsibility and democratic vision with one of cruelty, fear, and commodification. Until educators, artists, intellectuals, and various social movements address how the metaphysics of casino capitalism, war, and violence currently permeate American society (and societies in other parts of the world) along with the savage social costs it has enacted, the forms of social, political, and economic violence that ordinary people are protesting against, as well as the violence waged in response to their protests, will become impossible to recognize and counteract.

If acts of resistance are to matter, demonstrations and protests must give way to more sustainable organizations that develop alternative communities, autonomous forms of worker control, universal forms of health care, models of direct democracy, and emancipatory modes of education. Education must become central to any viable notion of politics willing to struggle for a life and future outside of predatory capitalism and the surveillance state that protects it. Teachers, young people, artists, and other cultural workers must come together to develop an educative and emancipatory politics in which people can address the historical, structural, and ideological conditions at the core of the violence being waged by the corporate and repressive state as well as begin to imagine a different collective future.

The issue of who gets to define the future not only rests on the questions of who controls global resources and who establishes the parameters of the social state. It also depends on who takes responsibility for creating a formative culture capable of producing democratically engaged and socially responsible citizens. This is much more than a rhetorical issue. Urgently required are new categories of community, identity, thought, and action that can form the basis for educating the public and generating broad-based structural changes. At stake here is the need for a language of both critique and possibility. Such a discourse will be utterly crucial for developing a politics that restores the promise of democracy and makes it a goal worth fighting for and winning.