Читать книгу George Guynemer, Knight of the Air (WWI Centenary Series) - Henry Bordeaux - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

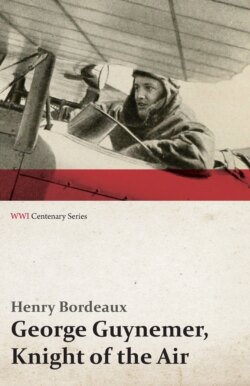

Air Warfare in the First World War

ОглавлениеIn 1903 the Wright brothers made the first recorded powered flight, achieving 12 seconds air time at Kittyhawk, Dare County, North Carolina, United States. In 1909, the first powered crossing of the English Channel was achieved by Louis Blèriot. Five years later, the First World War began.

Due to its still nascent technology, aviation was deemed of little use to the European armed services. One unknown British general commented that ‘the airplane is useless for the purposes of war.’ Likewise, the German General Ferdinand Foch is reported to have alleged that ‘aviation is a good sport, but for the army it is useless.’ These opinions reflected a widespread scepticism about aircraft, unsurprising given their delicate and undependable nature. Most aeroplanes in 1914 were constructed of hardwood or steel tubing, combined with linen fabric doped with flammable liquid to provide strength. They were incredibly fragile by later standards and frequently collapsed during flight, especially in combat situations.

As a result of these technical issues, when war erupted in July 1914, aircraft were used mainly for reconnaissance; feeding back information for artillery strikes, recording troop movements and taking detailed photographs of enemy positions. However, the diversity of uses, technological advances and sheer increase of numbers involved in air warfare during the period were astonishing. To illustrate, France had fewer than 140 aircraft at the outbreak of war, but by 1918 she had 4,500. However, France actually produced 68,000 aircraft during the war, with 52,000 destroyed in combat; a staggering loss rate of 77%. Aerial battles were extremely crude, but equally deadly – the pilots flew in tiny cockpits, making parachutes a rarity and death by fire commonplace. Many officers, especially the British, actually forbade the carrying of parachutes as it was feared they would lessen the fighting spirit of the men.

The typical British aircraft at the start of the war was the general purpose BE2X. It had a top speed of 72mph and was powered by a 90hp engine; it could fly for roughly three hours. By the end of the war, this had been replaced by planes such as the Sopwith Camel and the SE5a fighter, built for speed and manoeuvrability. The latter had a top speed of 138mph, now powered by a 200hp engine. The technological change which enabled these improvements was the ‘pusher’ layouts’ replacement. Traditionally, propellers faced backwards, pushing the plane forwards – but the alternative design with a forward facing propeller (a ‘tractor’) provided far superior performance both in terms of speed and power. Another major advance was the replacement of the rotary engine. In this type of engine, where the crankshaft remained stationary whilst the pistons (attached to the propeller) rotated around it, there was an excellent power to weight ratio, but it lost out to the more powerful water cooled engines. By 1918, the Sopwith Camel remained the last major aircraft still using the older rotary technology.

Within the first months of the war, whilst still in the ‘movement stage’, the value of aerial reconnaissance was vindicated. On 22 August 1914, contradicting all other intelligence, one British Captain and his Lieutenant reported that General Alexander von Kluck's army was preparing to surround the BEF. This initiated a massive withdrawal towards Mons, saving about 100,000 lives. Similarly, at the First Battle of the Marne, General Joseph-Simon Gallieni was able to achieve a spectacular victory, using information provided by the French air force to attack the exposed flanks of the German army. But nowhere was the importance of aerial intelligence more forcibly asserted than at the Battle of Tannenberg on the Eastern Front. The Russian General, Alexander Samsonov ignored his own pilot’s warnings, allowing almost all of his army to be captured or killed by the Germans. After the crushing defeat, Samsonov committed suicide whilst German Field Marshall Hindeburg stated ‘without airmen, there would have been no Tannenburg.’

As aerial reconnaissance became more frequent and effective, new methods were developed to counter this threat. At first, infantry fired at planes from the ground, although this was largely ineffective due to ill-adapted guns. Yet quickly, airmen began directly attacking one another. Pilots and their observers attempted to shoot at the enemy using rifles and pistols; some threw bricks, grenades and ropes with grappling hooks attached. A more reliable solution was required. As early as 1912 the Vickers company had already produced an experimental airplane to be armed with a Maxim machine gun. Nicknamed the ‘Destroyer’, the EFB1 plane was powered via the old fashioned pusher layout, allowing the gunner to sit in front of the pilot, giving an uninterrupted field of vision. The nose was too heavy with the machine gun’s weight though, and the plane crashed on its first flight. By 1914 many pilots took the initiative and experimented with machine guns themselves. The British pilot Louis Strange improvised a safety strap allowing the observer of his tractor driven Avro 504 to ‘stand up and fire all round over top of plane and behind.’ Similarly, on 5 October, 1914, a French pilot in a Voisin III pusher biplane became the first man of the war to shoot down another aircraft – his observer standing up to fire a Hotchkiss machine gun.

Only a few machine guns were small and reliable enough for use however, and the problem was not satisfactorily solved until Anton Fokker developed the ‘interrupter gear’ in 1915. This meant that a machine gun could be synchronised with the moving propeller blades – soon to produce the ‘Fokker Scourge’ for the allies. This development gave the Germans a strong advantage, not only strategically but in terms of morale. The Fokker, and its successor the Eindecker caused panic in the British parliament and press; also contributing to German successes at the Battle of Verdun as French reconnaissance failed to provide information on enemy positions. It took the allies an entire year to adapt the device to their own use.

These fighting aircraft were supported by the bombers; not directly involved in fights (if possible), but aimed at destroying the enemy’s capacity to make war on the home front. Industrial units, power stations, shipyards and entire cities became targets; some of the most famous being Germany’s Zeppelin raids on London – causing up to half a million pounds of damage with each vessel. At the start of the war, bomb aiming was crude in the extreme however. Bombs were simply dropped over the side of the aircraft when the pilot reached the vicinity of the target. Russia was the first to develop an airplane specifically for this purpose; the Murometz, a large four-engine airplane originally produced in 1913 as a passenger plane, was used successfully throughout the entire war. The Germans had the Gotha bomber plane, and the British had the Handley Page. Yet despite the strategic importance of these bomber planes, as the war continued it was the fighters who captured the public’s imagination. Popular legends arose around the ‘great aces’ such as Manfred von Richthofen (the ‘Red Baron’), Ernst Udet, and the French pilot Paul Rene Fonck. Governments were quick to trumpet the successes of their airmen for propaganda purposes, with the French and the Germans being the first countries to award the distinction of ‘ace’.

This seemingly exotic and elegant war in the air was far removed from reality however. As noted, reconnaissance was the largest role of aircraft during the war, and the bravery of the pilots in fulfilling this dangerous and unglamorous work is seldom remarked. Newly recruited pilots were sent into the sky, often only with a few hours air training time (typically less than five), and as the war progressed it became unusual for new pilots to survive their first few weeks. The newer planes, often built more for manoeuvrability than stability were increasingly difficult to operate and if pilots were not shot down, bad weather, mechanical problems and simple pilot error could all intervene. Most died not in spectacular dogfights but after being shot from behind, unaware of their attackers.

Taken as a whole, air warfare did not play a fundamental strategic role in World War One, as it did in later conflicts – however bombers and fighters provided just as important a psychological weapon as they did a practical one. The main significance of World War One aviation was a rapid increase in technology and prestige, fostering a new found respect in the general public and military commanders for this hitherto unknown method of battle. The terrible capabilities of air warfare would be unleashed on a far greater scale in the next World War, with even more devastating consequences.

Amelia Carruthers