Читать книгу The Five Walking Sticks - Henry R Lew - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление

Dear Reader,

Thank you for starting “The Five Walking Sticks.” I hope the title titillated your imagination. It was designed to arouse your curiosity, to entice you to see what my tale is all about.

“The Five Walking Sticks” describes the life of a man. His is not a household name and you have probably never heard of him. But his story is most unusual and certainly more fascinating than many others that relate to the rich and famous. One doesn’t have to be well remembered to have had a remarkable life and the reader certainly does not miss out on the rich and famous by travelling through the pages of this one.

But “The Five Walking Sticks” is much more than the life of a solitary human being. It is a course of study, a curriculum of history, anthropology and civilisation, which physically takes you into one of the most astonishing places on earth, the city that the British journalist George Augustus Sala dubbed “marvellous Melbourne” in 1885.

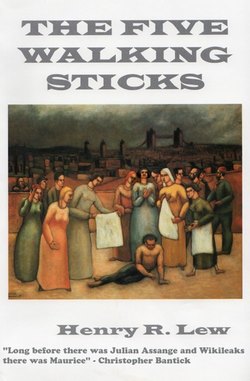

The central character Maurice Brodzky was very well known in Melbourne from 1885 to 1903. He was a most interesting and intelligent man and the role, which he played, was both important and valuable. That we know so little of him today is because rich and powerful opponents helped sanitise Melbourne’s history of him and later day historians continued this neglect. Michael Cannon in “The Land Boomers” is the sole exception. Indeed Cannon went so far as to describe Brodzky’s muckraking exposes, of the land boom and bust period, as “a record of individual public service which, it is safe to say, has never been surpassed anywhere in the world.” We are fortunate that sufficient information has survived to make a book possible. I cannot guarantee every single fact in this book as it directly relates to Maurice Brodzky. To ensure continuity I have on rare occasions filled the cracks in the plaster by insinuating myself into Maurice’s situation and writing the story as I imagined it would have happened. I don’t apologise for this for my aim has been to provide you with what I feel is the true spirit of the man even if history has at times been slightly stretched in the process.

Marvellous Melbourne, in 1890, was a cutting edge, avant-garde, cosmopolitan, multicultural metropolis, much as it is today. It was not at all the conservative Victorian Anglo-Saxon city into which I was born in 1948 and I must admit that my schoolteachers never told me it had ever been different. I hadn’t realised to what extent the Gold Rush and its aftermath had encouraged people from all parts of the globe to seek Melbourne out. I should have. I knew of Australian explorers named Burke and Wills but I also knew of Leichhardt and Strzelecki. I knew of Melbourne artists named Von Guerard, Chevalier, Buvelot, de Loureiro, Kahler and Nerli to mention only a few. And don’t we owe our Botanical Gardens, the most beautiful example in the whole wide world, and the main jewel in our beautiful city’s crown, to a man named Von Mueller? Two depressions and two world wars made our city less multicultural and more Anglo-Saxon and it was left to the Olympic Games of 1956 to recreate it as it was, to reactivate the merry-go-round that seems to epitomise human history.

I found out then as now we similarly had politicians famous for their double standards, some big businessmen who went profitably broke with other people’s money, and other ones very active in political circles using their politically acquired connections as a means of enriching their own coffers. And likewise there were people then, as now, like Maurice Brodzky, who believed men and women are equal, that people with religious beliefs different from the majority are no less worthy, and that Caucasians, Asians, and Aborigines are all cast out of the same mould and should be regarded and treated as such. Albert Einstein said in 1929 that homosexuality should not be punishable except to protect children and that a woman should be able to chose to have an abortion up to a certain point in pregnancy. People today who claim originality for such statements on social and moral issues are far from original. These things have all been said before. We can still learn our lessons from history. Scientific technology advances quickly but human nature and behaviour doesn’t.

Melbourne in late Victorian times like today was changing rapidly. The telegraph, which enabled news from Europe to be printed in Melbourne’s newspapers the following day, rather than two to three months later, was as big an advance as anything happening now. And in Melbourne last century the trams were privately owned, the trains were privately owned, the electricity, gas and telephone companies were privately owned and an ophthalmologist named Dr. Wolff was advertising in a manner that ten years ago would have been regarded as strictly unethical. And as I sat and watched our penultimate Premier Mr. Jeffrey Kennett allowing all these things to happen again I could only smile as he argued that he was taking us into the future.

I went through several titles before deciding on “The Five Walking Sticks”. There is an interview that Maurice conducted with the elderly journalist Edmund Finn better known as “Garryowen.” Finn on opening his front door introduced our hero to his five most cherished friends, his named collection of walking sticks. One of these was surprisingly called “the Rabbi.” As Maurice was Jewish this struck a chord. For Maurice too had five cherished friends, his languages of Hebrew, German, English, French and Latin, each of which he had mastered like a native. And as was the case with Finn, they gave him the freedom to walk wherever he wished, they were his five walking sticks.

Three people in particular helped me in the construction of my tale. My greatest collaborator was Maurice Brodzky himself. The middle third of my book which deals with Table Talk rests mainly on his own writings. I have not re-written them. Rather I have edited them, sometimes severely, sometimes lightly, to make them more friendly for the contemporary reader. This makes the middle third of my book somewhat different in style from the rest but I felt obliged to leave it in this form if I was to convey to you the essential spirit of this most interesting and unusual man. Richard Brodney and John Brodzky, Maurice’s grandsons, also helped by giving me copyright to Maurice’s unpublished writings and also to the works of their respective fathers Spencer Brodney and Horace Brodzky.

My own son Alexander Lew encouraged me to write the story in the first person. I wish to thank him for this. I was dubious at first but I now feel it was the correct way to go. If you enjoy this story one percent as much as I have then it has all been worthwhile.

Yours sincerely,

Harry Lew,

Melbourne, April 2000