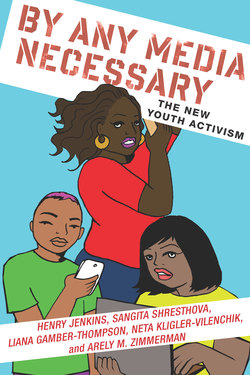

Читать книгу By Any Media Necessary - Henry Jenkins - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

“Watch 30 Minute Video on Internet, Become Social Activist”?

Kony 2012, Invisible Children, and the Paradoxes of Participatory Politics

Sangita Shresthova

Right now, there are more people on Facebook than there were on the planet 200 years ago. Humanity’s greatest desire is to belong and connect. And now we see each other. We hear each other. We share what we love and it reminds us of what we all have in common. And this connection is changing the way the world works. Governments are trying to keep up. The older generations are concerned. The game has new rules.

—Kony 2012

Sorry, it appears your system either does not support video playback or cannot play the MP4 format provided.

In spring 2012, Invisible Children (IC), a San Diego–based human rights organization, released Kony 2012, a 30-minute video about child soldiering in Uganda. In a central feature of the film, Jason Russell, one of the group’s founders and longtime leaders, speaks as a father to his young son about the evils perpetrated by the warlord Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The film ends with a call for supporters to help circulate the video in order to make Kony “famous,” criticizing the lack of Western media coverage of his atrocities and demanding that the U.S. government take action to end his reign of terror. IC anticipated that the well-crafted video might reach half a million viewers by the end of the year, based on its extensive experience deploying online videos. Instead, Kony 2012 spread to more than 70 million viewers over the first four days of its release and over 100 million during its first week in March 2012. By comparison, Modern Family, then the highest rated non-sports and non-reality program on U.S. television, was attracting a

little over 7 million average weekly viewers (based on published Nielsen ratings), and The Hunger Games, the Hollywood blockbuster released on March 23 of that year, drew an audience of approximately 15–19 million during its first weekend (based on ticket sales reported by boxofficemojo.com). Inspired by the video’s celebration of the power of social media, IC’s young supporters demonstrated how grassroots networks might shift the national agenda.

The speed and scope of the pushback against Kony 2012 was almost as dramatic as its initial spread. IC and its supporters were ill prepared for the video’s movement from a relatively tight-knit network of people who knew about the organization and its mission to a much larger population learning about Kony for the first time as someone they knew posted the video on Facebook, forwarded it by email, or blasted it via Twitter. Kony 2012 drew sharp criticism from many established human rights groups and Africa experts, who questioned everything from IC’s finances to what they characterized as its “white man’s burden” rhetoric. IC was especially challenged for being out of sync with current Ugandan realities and promoting responses some argued might do more harm than good. Critics saw Kony 2012 as illustrating institutional filters and ideological blinders that have long shaped communication between the global North and South.

Kony 2012 became emblematic of a larger debate concerning attention-driven activism. In a blog post written in Kony 2012’s immediate aftermath, Ethan Zuckerman (2012a) surveys the critiques leveled against the video, stressing that it gained broad and rapid circulation by grossly oversimplifying the complexities of the conditions in Africa and creating heroic roles for Western activists while denying the agency of Africans working to change their own circumstances. Zuckerman explained: “I’m starting to wonder if this [exemplifies] a fundamental limit to attention-based advocacy. If we need simple narratives so people can amplify and spread them, are we forced to engage only with the simplest of problems? Or to propose only the simplest of solutions?” This question haunts not only IC supporters, but leaders of many other activist groups.

By the time Kony 2012 hit, our team at USC had been studying Invisible Children for three years. We first learned about IC through one of its early, and still controversial, media artifacts, a short dance film entitled Invisible Children Musical (2006), which was a takeoff of Disney’s High School Musical. In this film, IC’s founders turned to popular culture, song, and dance to reach and inspire young people to take part in the Global Night Commute, a multisited live event. The Invisible Children Musical polarized our research group when we watched it during our weekly meeting. Some members were intrigued, even excited, by its unabashed appropriation of popular culture. Others literally pushed themselves away from the conference table to express their negative reaction to the film’s extravagantly celebratory and admittedly simplistic messaging.

As we learned more about the organization’s media and activities, we quickly understood that pushing the boundaries of youth activism was an integral, though not always completely intentional, part of IC’s efforts. Through a series of research projects focused on various facets of IC—including learning, transmedia storytelling, and performativity—we delved deeper into understanding the group’s media, staff, and supporters. Over the years, we observed many IC events in Southern California. We attended film screenings and watched many hours of IC media. We were invited to attend events that the group organized and visited its headquarters in San Diego many times. We interviewed 45 young people involved with IC and had regular interactions with the group’s leadership.

Our ongoing contact gave us a unique vantage point from which to observe IC as it moved from a relatively obscure initiative to an extremely visible (and overly scrutinized) organization that was asked to publicly account for all its decisions. We were also privy to the profound personal and organizational challenges IC faced as the situation around Kony 2012 escalated. And, we were part of a small group of researchers IC continued to trust after 2012. As one staff member observed in 2013, Kony 2012 had forced IC to “grow up” overnight; we were able to observe this change firsthand.

Nick Couldry (2010) begins his book Why Voice Matters by identifying the many different ways voices get denied or undermined within today’s neoliberal society. IC’s supporters were mostly drawn from the ranks of more affluent and politically influential sectors of society (see Karlin et al. forthcoming.) Surely, these youth have access to many of the levers (Zuckerman 2013a) needed to make their voices heard. Yet many of them had not been involved in civic life before and would not have become politically active without IC’s supportive community. In this book’s later chapters, we will see more dramatic examples of marginalized groups seeking collective power through participatory politics, but it’s worth stressing that political engagement is not guaranteed even among those who come from more privileged backgrounds. Supporting this perspective, Kligler-Vilenchik and Thorson (forthcoming) show how memes critical of Kony 2012 exploited stereotypes that young people are ignorant, irrational, duped, or apathetic. Couldry (2010) reminds us, “People’s voices only count if their bodies matter,” noting that existing forms of discrimination based on race, gender, sexuality, and so forth ensure that some voices go unheard (130), and we must surely add to that list the marginalization which has historically occurred as children and youth first assert themselves into political debates. Couldry also reminds us that “an unequal distribution of narrative resources” may also serve to limit which voices can be heard, since some forms of political speech are more readily recognized than others within institutional politics or journalism (9). The groups we are studying are seeking to expand the languages through which politics can be expressed, finding new vocabularies that make sense in the life contexts of young citizens; as they do so, however, they may often express their messages in ways that make them less likely to be heard by key decision makers.

In this chapter, we use IC and Kony 2012 to explore the potentials and challenges of participatory politics. Three years after the film’s release, we remain distinctly ambivalent about whether the film’s immense spreadability translated into a net success for the organization and the youth movement it inspired. We thus use IC and Kony 2012 to identify some of the paradoxes that must be addressed if we are going to understand whether and in what ways the mechanisms of participatory politics might promote meaningful political change and foster greater civic engagement. The paradoxes we identify here reflect recurring questions the organization faced during this period of crisis and success: How much should IC focus on expanding the youth movement it had built up through the years via its focused anti-LRA efforts? Could IC accept its members’ desire for a more participatory organizational model or should it try to retain control over their messaging? Could the story IC told be both simple enough to be easily graspable and complex enough to do justice to the nuances of the LRA conflict? How could IC make its humanitarian and social justice work fun without compromising its acceptance by policy makers and NGOs? And why didn’t IC work harder to balance the friendship and cordiality it so treasured with training that equipped its supporters to deal with contentious situations related to its cause? Above all, should this innovative organization be judged based on the results it achieved in pursuit of its policy goals or based on the ways it recruited and empowered a generation of young activists who might have an impact on a broader range of issues?

We watched IC’s leaders and supporters twist and turn as they experimented with different responses to these core paradoxes; we saw the group move between models that were more top-down or goal focused and others that were more participatory and process focused. The enormous success of Kony 2012 brought all of these tensions to a crisis point from which the organization never fully recovered. Each of the groups in our other case studies confront some of these same tensions; each represents a somewhat different model for how successful organizations might solicit and support the participation of their members in an age of networked communication; each group made its own choices, and, yes, its own mistakes, as they sought to address these defining challenges around civic culture in the early 21st century. Few of the cases, though, illustrate these paradoxes as fully as IC does and that’s why we are starting here.

Moving beyond the Clicktivism Critique

On August 8, 2013, Jason Russell addressed an auditorium full of young IC supporters. After some initial lighthearted comments, his demeanor changed. “I want to give you a little glimpse into what was going on inside of me,” he said. He then recounted the days following Kony 2012’s release that led up to his public mental breakdown. “I wrote down all the things that we were pissing off, that we were disrupting, that we were questioning,” he recalled. “The list looked like this: Hollywood, social networking, online media, movies, activism, United Nations, America, millennials, journalism, nonprofits, fashion, advertising, and international justice.” He explained that’s when he realized “why they’re so pissed off.” In his words, it was “because it’s … the whole world that is going, ‘Who is this? Who are you? How dare you load a 29-minute 59-second video online? And how dare you reach 120 million people in five days? That’s not allowed. Something must be fishy. You must be a scam.’” At this point, his usually enthusiastic audience fell silent. Russell’s recounting of his personal experiences took everyone back to the moment when the initial excitement about Kony 2012’s phenomenal spread gave way to the backlash against Russell, Invisible Children, and the group’s young supporters. In Move, a film IC released in the fall of 2012, IC communication director Noelle West described her experience:

My cloud nine quickly dissolved.… Our website wasn’t built to maintain 35,000 concurrent viewers at one time. So our website’s crashing intermittently. The only thing we could communicate through was Tumblr. So you’re not going to see information about every single thing that we do from a Tumblr. And that was, I think, the beginning of the conversation turn from “this was the greatest thing on the planet” to “what the hell is this?”

In the same film, Russell described the criticism as a “tsunami” that IC “didn’t see coming.” In his words, “We turned around, and we were all under water.”

Something of the vicious tone of the critiques is captured in comments from Ugandan activist, social media strategist, and blogger TMS Ruge (2012a), who defined Kony 2012 as “another travesty in shepherd’s clothing befalling my country and my continent.” To Ruge, the film was “so devoid of nuance, utility and respect for agency that it is appallingly hard to contextualize.” Ruge, along with other critics, also questioned the effectiveness of purchasing “a T-shirt and bracelet” as acts that would somehow end a two-decade-long conflict. Other critics accused IC of exploiting the naiveté and ignorance of its young supporters, who they feared would confuse the feel-good process of spreading a YouTube video with the hard work involved in changing a complex international situation.

One internet meme summed up the phenomenon: “Watch 30 Minute Video on Internet, Become Social Activist.” This meme is, in many ways, emblematic of a larger critique of so-called clicktivism, defined as the application of the metrics and methods of the marketplace (number of clicks) to measure the success of (arguably) activist efforts. As one critic explains, “The end result is the degradation of activism into a series of petition drives that capitalise on current events. Political engagement becomes a matter of clicking a few links. In promoting the illusion that surfing the web can change the world, clicktivism is to activism as McDonald’s is to a slow-cooked meal. It may look like food, but the life-giving nutrients are long gone” (White 2010). The clicktivist critique often describes online campaigns as involving limited risk or exertion and having limited impact on institutional politics.

A meme that critiqued and ridiculed the Kony 2012 campaign.

The New York Times’ Room for Debate introduced its discussion of Kony 2012, tellingly titled “Fight War Crimes, without Leaving the Couch?” (2012), with this provocation: “Social media definitely have the power to bring attention to terrible problems—but is there a downside, if the ‘call to action’ is wrong-headed or if these campaigns give young people a false sense of what it really takes to create change?” While networked communications has made it easier for citizens to access and act upon information, making it possible for movements like Kony 2012 to achieve remarkable speed and scope, we must keep in mind these developments have not always been seen as a positive thing.

Indeed, the most persistent skepticism centers around whether these new platforms and practices make it too easy to take action without ensuring that people have time to reflect. Writing in the midst of the boom and bust surrounding the video, Mark A. Drumbl (2012) concluded: “The Kony 2012 campaign—and clicktivism generally—have short attention spans and limited shelf life” (484). Some speak about compassion fatigue in a world where political messages get carried by dramatic and simplified videos and then diminish as participants feel the tug of yet another story and another appeal for action. The premise that IC’s supporters could achieve dramatic results by mobilizing massive numbers of people online was resoundingly ridiculed by memes, ironically generated and circulated by other internet users, such as one that announced, “You shared Kony 2012? Congratulations—you saved Africa.” Malcom Gladwell’s (2010) critique that Twitter revolutions involved lower risks than previous political movements was expressed by another widely circulated cartoon depicting an exchange between activists of two different generations. The older one, wearing an eye patch, explains, “I lost my eye in a five day student protest in 1970,” while the younger one explains, “I just sprained my clicking finger joining a Facebook protest group.”

Neta Kligler-Vilenchik and Kjerstin Thorson (forthcoming) identified and tracked 135 such memes circulated in response to the Kony 2012 campaign, almost all of which were negative in their characterization of IC and its efforts. They saw such memes as part of a struggle over what constitutes good citizenship, with the memes mostly referring back to classic conceptions of the informed citizen some felt were under threat from Kony 2012’s more networked model of participation. Michael Schudson (1999) and Roger Hurwitz (2004) have discussed a shift from the older model of the informed citizen toward an emerging model of the monitorial citizen. Under the informed citizen model, people need to possess full knowledge of an issue before they can act politically. Given the complexity of many contemporary issues, this standard is often impossible to achieve and the failure to meet expectations based on it can result in a sense of disempowerment. By contrast, in a networked society, people can monitor specific concerns and then use social media to alert each other to issues requiring greater attention or collective action. We can see the circulation of these political videos as one mechanism through which monitorial citizenship works. Kligler-Vilenchik and Thorson conclude that the anti–Kony 2012 memes “may suppress budding political interest and engagement” by dismissing both a political cause that engaged many young people and ridiculing the forms of political participation they chose to make their voices heard: “young networked citizens may be experimenting with new ways not only to become informed, but to act on that information.”

A meme created by Peter Ajtai of insert-joke-here.com pitted generations against each other in the slacktivism debate.

If all that happens is the spread of a video, then the system of monitorial citizenship will have failed. However, our research shows that this is not what happened with Kony 2012, nor was it what IC intended when it released the film. On the contrary, IC saw such circulations as a point of entry into more intense kinds of political engagement. A high percentage of those reached by such social awareness campaigns may well shift their attention elsewhere, but some research (Andresen 2011) suggests that the act of passing along a video increases the likelihood that participants will take other kinds of action in support of the cause, including contributing time and money. A large part of IC’s argument for “making Kony famous” was that, for many years, his atrocities received relatively little media coverage and escaped intense scrutiny from the international community. The group hoped that increased awareness would result in shifts in media coverage and public policy that would hinder the LRA’s mobility.

Echoing this, the IC supporters we interviewed post–Kony 2012 made very realistic claims about the effectiveness of online advocacy campaigns. Nineteen-year-old Johnny discussed writing a class essay critiquing Gladwell’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted.” He explained his perspective: “[Facebook and Twitter] definitely can be used as a medium to gather people, to get attention, but it can’t be the only thing. At the end of the day, you need bills to be passed. You need money to be raised, but if that [social media] can be used to spread awareness and get the word out and help these things be achieved, that’s great. Kony 2012 proved that.” Johnny described the video as a catalyst setting other things into motion, creating the awareness and support that enabled Congress to pass laws impacting what was happening in Africa. In his model, participatory and institutionalized politics worked together to achieve the desired results.

IC offered its members varying degrees of participation, including involvement in large-scale mass gatherings and attendance at training sessions, while it also worked more directly with elite institutions and political power brokers. In fact, many of the supporters we met saw the range of participation IC offered and the “hip” tone of these engagements as crucial to the group’s appeal to youth. Stephanie, an IC college club member, confirmed this when she observed that the organization “is really good about having different campaigns” that offer multiple ways to participate and many points for potential engagement that might begin, for instance, with attending an IC screening and grow over time. The bucket list of IC-related activities the youth described included organizing local IC events (often designed to be celebratory in tone), creating their own media to recruit members for local clubs, using social media to maintain support, setting up information tables at their local school or college, designing T-shirts, fundraising toward specific IC goals, and even interning or touring with IC. To Janelle, who was interning with IC at the time of her interview, the key to IC’s success with young people is their “youthful, hip vibe,” which she attributed to the fact that “everyone in the boardroom is 30 years and younger.” As Stephanie reflected on her IC experience, she also appreciated the support and advice she received in running her local club as IC’s responsive staff helped her navigate various logistical and organizational challenges.

Over time, IC supported more explicit political lobbying efforts. For example Jack, a college sophomore, described the ways that IC had enabled him to directly contact Senate staffers during a visit to Washington:

The fact that the staff members of a senator could actually listen to a 17-year-old was pretty amazing.… [IC does] a very good job of preparing us.… The lobbying meetings I’ve attended in the last few years have been based around specific legislation or resolutions that they’re seeking to pass or, you know, stuff like that. So you get a point of contact from the office and then they send us—they put together, you know, guides, very detailed guides, for both the lobby people leaders and, then, if you have first-time lobby members in your group, they have specific guides for them. And they detail everything from what you should wear to a meeting to what you should talk about.

Jillian, a 22-year-old from Pennsylvania, similarly described the ways that IC provided her and her classmates with the scaffolding they needed to deal directly with their elected officials. She noted that the IC staff members would often call to debrief with her team on what worked or didn’t after a meeting took place. The tendency to reduce Invisible Children to a 30-minute video undervalues the much broader array of media tactics the group deploys. Similarly, the idea that this movement depends primarily on short-term reactions to rapidly spreading content underestimates the number of young people who have participated in afterschool organizations, been trained by the roadies who travel the country showing IC films and leading workshops with supporters, gathered for massive scale public protests, attended one of the Fourth Estate conferences, or flown to Washington to lobby government officials.

Clicktivist critiques simplify our understanding of the political life of American youth. Right now, young people are significantly more likely to participate in cultural activities than engage with institutional politics. As a consequence, those activist groups that have been most successful at helping youth find their civic voice often tap into participants’ interests in popular and participatory cultures, frequently blurring the distinction between what Mizuko Ito and her colleagues (Ito et al. 2009) categorized as friendship-driven and interest-driven modes of participation online. Ito et al. define friendship-driven modes as “dominant and mainstream practices of youth as they go about their day-to-day negotiations with friends and peers” (15). Such friendship-driven networks are often a “primary source of affiliation, friendship, and romantic partners” for youth. In contrast, interest-driven practices are rooted in “specialized activities, interests, or niche and marginalized identities.” Ito et al. clarify that the interest-driven activities often reside within the “domain of the geeks, freaks, musicians, artists, and dorks” (16). Kahne, Lee, and Feezell (2011) closed the circle between interest-driven activities and civic engagement when they examined how young people’s interest-driven online activities may “serve as a gateway to participation in important aspects of civic and, at times, political life” (15) and found a correlation between young people’s interest-driven participation online and increased civic behavior, including volunteering, group membership, and political expression.

Our research found significant overlap between friendship and interest-driven engagement among IC participants. In their analysis of IC interviews, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik and her colleagues (2012) identified “shared media experiences” (gathering around texts that have a shared resonance), sense of community (identifying with a collective or network), and a wish to help (a desire to achieve positive change) as three key components of participants’ IC experiences. For a vast majority of the youth interviewed, all three components intersected with their “friendships” and “interests” as they chose to take action with their friends around issues they cared about. Ruth, who was an intern at IC’s offices in 2010, described her experience: “Invisible Children is a lot about relationships.… You work together, you play together, you eat together.” To Janelle, another intern, this approach results in a “complete great intertwining” of work and fun at IC, making it hard to separate the two. Like Ruth and Janelle, many other IC supporters felt that the group’s social elements were crucial to their sustained participation.

Similarly, many interviewees felt that “shared media experiences” significantly contributed to this sense of connection between IC youth. Melissa Brough (2012) traced the early history and tactics of Invisible Children, stressing that the group has long placed a high priority on media production as a means of creating awareness but also recruiting and training a movement of American young people determined to impact human rights concerns in Africa. Jason Russell and Bobby Bailey, recent graduates of the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts, along with Lauren Poole, who was enrolled at the University of California, San Diego, established Invisible Children in 2006 as an outgrowth of their documentary film Invisible Children: Rough Cut (2006), which called for the capture of Joseph Kony and fundraised for on-the-ground recovery efforts. The organization grew rapidly: Brough recounts that within six years, they had built an organization with 90 staff on the ground in Uganda running development programs, 30 paid U.S. staff managing outreach, a fundraising apparatus that brought in almost $32 million in 2012, and a network of more than 2,000 clubs in schools and churches. The group’s commitment of more than 9 percent of its budget to media making and another 35 percent to mobilization of youth in the United States became yet another site of controversy as Kony 2012 brought new scrutiny of the organization. Lana Swartz (2012) has similarly noted the diverse range of different media practices the group deploys:

“The Movement,” as Invisible Children calls its U.S.-facing work, includes visually arresting films, spectacular event-oriented campaigns, provocative graphic t-shirts and other apparel, music mixes, print media, blogs and more. To be a member of Invisible Children means to be a viewer, participant, wearer, reader, listener, commenter of and in the various activities, many mediated, that make up the Movement. It is a massive, open-ended, evolving documentary “story” unfurling across an expanding number of media forms.

Brian explained in an interview how IC’s media moves people to action: “There is just no way that if you have a beating heart and a pulse in you, that you can watch any of their films and not be moved into action afterwards.… [T]here is always something that resonates within you, just, wow, this is powerful.” IC youth we met were proud of the group’s media, which they saw as central tools in spreading its message.

Spreading Kony 2012

There has been a tendency to deal with Kony 2012 in isolation from the much longer history of IC efforts to rally public opinion against the African warlord. By the time IC released Kony 2012, the group had produced and circulated ten previous features and many shorts; helped get legislation passed in 2010; formed local clubs through high schools, colleges, and churches; recruited and trained thousands of young activists through intern programs, summer camps, and conventions; demonstrated the capacity to mobilize those supporters through local gatherings and demonstrations across the country; developed a large-scale operation on the ground in Africa and brought Ugandans to the United States to interface with American recruits; set up a Ugandan and American teacher exchange program; and run national conventions designed to train young activists so that they could explain what was happening in their own words. Kony 2012 did not simply “go viral” out of the blue; rather, IC had sustained a community and tested strategies of grassroots circulation that reached diverse participants and laid the groundwork for the film’s extraordinarily rapid dissemination.

Supported both through top-down distribution efforts and bottom-up, peer-driven media circulation, the film’s release relied on what Jenkins et al. (2013) call “spreadability” or an “emerging hybrid model of circulation, where a mix of top-down and bottom-up forces determine how material is shared across and among cultures in far more participatory (and messier) ways” (3). As we think about this spread of Kony 2012, we might consider different moments of participation as an alternative to the clicktivism model.

A core group of young supporters who had been recruited and trained over many years through clubs at churches, schools, and colleges took the first steps in sharing the film with their peers. The video then circulated via friends, families, and others within their social networks. Gilad Lotan (2012), a researcher for Social Flow, discovered that the earliest and most active retweeters of Kony 2012 came from midsized cities in the Bible Belt and Middle America (including Birmingham, Indianapolis, Dayton, Oklahoma City, and Pittsburgh), cities where there were already many active IC chapters. He also discovered, looking at the personal profiles of those early supporters, that many of them displayed signs of strong religious commitments, as well strong ties to their former (or current) high schools and colleges. Part of the group’s tactics involved getting fans to target high-profile policy makers and “culture makers,” often celebrities known to have strong online followings, in hopes that they would retweet and thus further amplify the message, precipitating greater coverage through mainstream media outlets. Finally, the video provoked responses from concerned others including critics in public policy centers in the United States, critics from the global South who also use digital media to engage within political debates across geographic distances, and other young people who challenged their friends’ grasp of what they were circulating.

A visualization created by Gilad Lotan mapped the initial spread of the Kony 2012 film.

Each of these sets of participants had a different relationship to the organization and its message. As the video traveled outward from the initial cadre of hardcore supporters, there was a greater risk of what danah boyd (2014) calls “context collapse.” For the hardcore supporters, Kony 2012 was understood in relation to the larger IC story: for example, while critics saw something patronizing in the way Russell was explaining the human rights issues to his young son, longtime supporters saw the video as a moment of maturation, having first seen Russell as a hapless college student in the Rough Cut, in contrast to his now stepping into a different—more adult and responsible—role. Meanwhile, the context critics felt was missing from this particular video, including the inclusion of a substantial number of African voices, was more fully developed in other videos the organization had produced. Tony (2011), for instance, the film IC released prior to Kony 2012, focused specifically on the long-term relationships the group’s founders had developed with Ugandan youth and auto-critiqued the culturally naive blunders they had made along the way.

IC’s deployment of social media as a channel for circulating Kony 2012 allowed it to gain much greater visibility than if the nonprofit had been forced to rely exclusively on broadcast media, whether through public service announcements or “earned” media coverage. Yet at the same time, this strategy meant that the group could not fully control where or how the video spread. IC underestimated what Lissa Soep (2012) has described as the “digital afterlife” of the film, in which “the original intentions of media producers are reinterpreted, remixed and sometimes distorted by users and emerge into a recontextualized form” (94). This is a problem encountered by many groups that have sought to deploy such practices. One could argue that even the pushback from African political leaders and commentators reflected the new openness that could be achieved in a system where there was more grassroots control over the means of production and circulation; a traditional public service announcement might never have been seen by these Africa-based critics and, similarly, American supporters of Kony 2012 would never have heard these critiques in a more localized media ecology.

Kony 2012 is now often held up as the extreme example of a message that was widely circulated, but which did not result in meaningful change. More than three years after the film, Joseph Kony remains at large, a fact that is often cited as the ultimate proof of Kony 2012’s failure. Some of IC’s critics also find evidence for the meaninglessness of the film’s popularity in the subsequent Cover the Night initiative, which asked young people to hang Kony 2012 posters in their neighborhoods on April 20, a little more than a month after the film’s release. Writing for Policy Mic, Shanoor Servai (2012) called Cover the Night “the anti-climax to the online brawl” over Kony 2012. To her (as to others), Cover the Night proved that a “movement that begins without face-to-face contact between its supporters is unsustainable.” While they certainly raise some valid points, these critics fail to acknowledge the turmoil into which the controversy surrounding Kony 2012 threw IC’s staff and supporters—undermining their ability to make the most of the film’s extraordinary reception—not to mention the extensive work the organization has nonetheless done to move online contacts into more extended face-to-face interactions among participants. More than that, such critiques ignore the actual policy changes the organization was able to achieve. Kony 2012 and IC directly contributed to the bipartisan passage of an expansion to the federal Rewards for Justice program, authorizing a reward of up to $5 million for information “that leads to the arrest of Joseph Kony.” Indeed, IC leadership was invited to the White House ceremony where President Obama signed the bill into law. Despite such policy accomplishments, however, Invisible Children has had to cut back on its budget and staff and faces ongoing institutional pressures even as it has moved to prioritize its activities on the ground in Africa post–Kony 2012.

Paradoxes of Participatory Politics

Invisible Children’s attempts to reinvent itself post–Kony 2012 give us a starting point from which to consider the contradictions and paradoxes associated with participatory politics. We do not necessarily see IC as an exemplar, and this discussion is not intended to endorse the group’s choices. But we hope to better understand some of the challenges youth-centered networks confront as they promote social change through participatory politics. In particular, we are pointing toward fault lines within the organization that have surfaced as different segments of the group’s leadership lobby for greater or less commitment to these competing principles and as different mixes of these traits dominate various films IC produces and various campaigns it launches.

Goals <—> Process

The tension between IC’s primary policy goals, to have Joseph Kony captured and to end the LRA’s atrocities, and its main activism objective, to expand the civic capacities of its young U.S. supporters, is the central paradox within the organization. In our first meetings with IC staff in 2009, they openly admitted to being “surprised” when they first recognized that their supporters numbered in the hundreds of thousands. At that time, IC also did not have any formal structures in place to organize and direct these young people’s desire to participate. Rather they relied on peer-to-peer personal connections between clubs and specific staff members to transfer knowledge that fell outside immediate IC-determined fundraising strategies. To IC’s leadership, the youth movement they had built was an unexpected outcome of their efforts to bring about the capture of Joseph Kony and support the rehabilitation of forcibly recruited child soldiers in the region.

A few months before the release of Kony 2012, IC assembled more than 650 of its most dedicated supporters for a gathering at the University of San Diego and announced that the event marked the launch of what they called Fourth Estate. While the term “fourth estate” has long been applied to the role of the press in a democratic society, IC used it to convey something different: the role of citizens in holding governments accountable. Between 2010 and 2014, IC organized three Fourth Estates. While they differed significantly in scope and size, they all took place over several days and included speeches and workshops designed to help “hardcore” IC supporters develop skills required to help the organization achieve its goals at that given moment. Here, IC shared plans with their most trusted supporters. As such, each conference provided unique insights into the organization’s shifting priorities and helped us track IC’s evolving relationship to participatory politics.