Читать книгу Cold Stone Jug - The Anniversary Edition - Herman Charles Bosman - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеSafe in the arms of Jesus,

Safe in Pretoria gaol –

Fourteen days’ hard labour

For cutting off a donkey’s tail…

(Song of the old reprobate in

WILLIAM PLOMER’S TURBOTT WOLFE, 1926)

EXACTLY fifty years ago Herman Charles Bosman’s Cold Stone Jug was published by APB Bookstore (that is, the Afrikaanse Persboekhandel) at 3 Plein Street, Johannesburg. To its devoted first readers the early prison background of their humorous columnist and literary man-about-town came as something of a jolt.

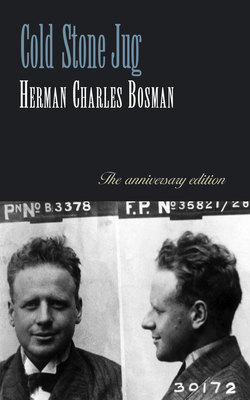

But in the Nominal Roll of Convicts, the great Domesday-book kept in the archives at the Little Reserve of Pretoria Central Prison of all the prisoners admitted there, his name is indeed entered in pen as Prisoner No. B3378: Bosman, Herman Charles, Race: E, Sex: M, with his crime, the date of conviction and the sentence. His age is given as 21 years, although he was in fact still twenty, in danger of not living through to his majority. When he referred to his prison years as an unnaturally prolonged adolescence he was not being inaccurate.

Cover of the first edition, 1947

Because he was a capital case due for execution, his double mugshots were pinned to the page, where they remain as a kind of memento mori to this day. Only a dozen or so of the condemned are commemorated in this manner, indicating that hangings in the Transvaal in the mid-1920s occurred rarely (say, one or two a month); they were reserved for murderers only. Of his opposite number in the condemned cells, the immaterial character named ‘Stoffels’ whom Bosman introduces to us in Chapter 1, there remains no trace.

In their ID shots the condemned are dressed in one of two ways: whites wear a striped jacket, a formal white shirt with detachable stiff collar and a neat black bow-tie, so that they go to meet their Maker like waiters at the Palm Court; blacks are posed in the same jacket and shirt, but without the collar and tie. All the doomed sport their original wavy locks or nappy mops; on Death Row a shaved head would mean that the prerogative of mercy had been exercised and the prisoner become a proper convict. Hangings were impressive rituals; after all, Francis Bacon had recommended attendance at them for their edifying effect.

The trial of Bosman for the murder of his step-brother, David Russell, was tried as Case 358 in the Witwatersrand Division of the Supreme Court of South Africa in Johannesburg, on 11 and 15 November, 1926, before Mr Justice Gey van Pittius, without jury but with two magistrates as assessors. The crime itself had been committed on the night of 18 July at the Bosman-Russell family home in Bellevue East. Bosman had been held as an awaiting trial prisoner at the Johannesburg Fort for four months – ever since the first Sunday at Marshall Square which he recounts in the Preamble.

Although the judge was obliged to sentence him to hang by the neck until he be dead – the words are plain enough in black ink on the registrar’s cover-sheet (Verdict: Guilty; Sentence: Death) – he added the respectful but very strong recommendation to the Governor-General that, in this “very sad and pathetic case”, sentence be commuted; the youth of the offender and the absence of any prior intention to kill could be considered as the mitigating circumstances. With the concurrence of his assessors he continued: “If I may be allowed to make a suggestion, I would also respectfully recommend, in case His Excellency the Governor-General should see fit to make a reprieve, that the period of imprisonment be not a lengthy one.” Bosman echoed these words in the epigraph to Cold Stone Jug where he describes the work as “a record of a somewhat lengthy sojourn in prison.”

The Nominal Roll kept in Pretoria indicates that the Governor-General, the Earl of Athlone, had done the right thing by Bosman over that Christmas, informing the registrar of the New Law Courts in Johannesburg on 28 December that Bosman’s sentence had been commuted to “imprisonment with hard labour for ten years.” In Cape Town on 10 January, 1927, the then Minister of Justice, Tielman Roos of General J. B. M. Hertzog’s long-lasting Pact government, signed the necessary Notice to the Sheriff. This was in due course ceremonially read to Bosman by the prison Governor in his death-cell (as recounted in Chapter 2).

The roll also notes that for commutation warrants and all other proceedings, including his daily behaviour record, one is to refer to the Convict’s Records, a folder unfortunately no longer preserved. But the roll does include several other inscriptions – for example, remission granted to all prisoners on the passage of the Flag Bill (this had dragged on as a divisive national issue since 1926, to be resolved finally by a joint sitting of both Houses in October, 1927): two months off. This detail brought Bosman’s date of discharge down to 14 September, 1936. (The Prince of Wales’s visit led to no reductions.)

So far the astute reader of Cold Stone Jug may have estimated: the roll merely corroborates and meshes with the evidence of Bosman’s own chronicle. Yet, in writing his record he was not so much intent on providing the reader with a documentary as with a more general narrative about the convict experience. By naming the institution ‘Swartklei Great Prison’ (instead of the ‘Pretoria Central’ where we know he did his time), he alerts us to his partly allegorical intention.

None the less, for the record, and in order to sort out his rather blurred mention in the final chapter that, like all his fellow inmates, he made a career inside of petitioning the powers that be for further remission of sentence, and that one day out of the blue a petition of his succeeded, it should be mentioned here that – according to the information nibbed into that immense record of life and death – he was indeed granted a second reduction. Following Authority No. 2666/W303, as noted on 30 April, 1930, Bosman’s term was then further commuted to “five years with hard labour.” So his date for release had now advanced to 14 September, 1931 (see PD/47/T.321 of 15 August, 1930); thus his last stretch of six years was dramatically reduced at a swoop to thirteen months. Whether this second reduction was thanks to his good behaviour, his fine style of petitioning or a general amnesty in South Africa (of which there is no evidence) is unclear. According to Bosman’s friend Fred Zwarenstein – his fellow school-teacher who became a lawyer, dedicatee of Bosman’s poem “Africa” and a courier of his work from prison – the string-pulling of Bosman’s uncle, Advocate Fred Malan, and the work behind the scenes of other petitioners, may have been influential.

The date of Bosman’s eventual release on probation remains unclear, however. According to the minutes kept in the State Archives of the meeting held in the Prime Minister’s office in Pretoria, by 13 August, 1930, the then Minister of Justice, Oswald Pirow, had already received the favourable report of the chairman of the Board of Visitors recommending Bosman’s release “as soon as possible.” This he endorsed and forwarded to the Governor-General, who the next day in turn approved the report in anticipation of the following meeting of the Executive Council. There it was likewise to be approved – on 12 September, 1930 – and signed by the Minister of Internal Affairs, D. F. Malan.

We know from Chapter 10 that, due to clerical bungling, Bosman’s release was then unduly delayed and he was not to emerge from that monumental door with its huge brass knocker and on to the public Klawer Street of the Pretoria prison reserve until November, 1930. Inside Pretoria Central Prison he had served almost exactly four years. The roll gives his day of release as 14 November, 1931, but that must apply to when he in due course successfully came off parole.

He had missed not only his coming-of-age party, and the notorious 1929 Black Peril election, but the worst of the Great Depression as well. He had been incarcerated as a youth during the jazzy, charlestoning, Art Deco Twenties. He was now an adult in a society of austerity.

What was the nature of his punishment?

In the late eighteenth century the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham correctly perceived that, with its flamboyant trials, grisly tortures and tumbrils through the crowded streets, the European system of correction was deeply symbolic. In his writings about the inspection house, published in 1791, he proposed the panopticon building in which inmates, suffering the illusion that they were under constant surveillance, would come to collude in an orderly fashion in their own subjection. The outward show of this routine – the initiation into prison life, its costuming, parades and processions – to this day retains the theatrical element which Bentham saw as essential to the process of acting out guilt and its rectification. The very structure of the Pretoria Central Prison building – four wings in cruciform, each with several storeys of galleries with balconies about the main, well-lit hall like a stage, where as part of the therapy actual plays and the annual Christmas concert are staged – suggests that Bentham’s utilitarian thinking long remained active. The whole of Chapter 7 in Cold Stone Jug, dealing with the food strike, takes place in this Benthamite space like a Piranesi Gothic nightmare, yet as a real-life drama, with all the disruption that occurs from when the audience begins pelting the performers through to authority’s devastating return to order in a brilliant coup de theatre.

In Bentham’s day punishment at the Cape followed Roman-Dutch law and was usually of the body in open display – breaking on the wheel, brandings and amputations – so as to regulate the imported slave and conquered indigenous population by terror. Whites were punished following military procedures. The most celebrated European offender against Company rule was the free burgher and diarist, Adam Tas. For his petition agitating against the Governor’s tariffs, as tourists to the Castle well know, he was incarcerated in its black and airless dungeon for all of thirteen months during 1706-07. Admiring this rebellious, contrary Jew, Bosman made a point on a return visit of his to the Cape in 1947 of inspecting the site of his ordeal and even sketching the Tas mausoleum.

According to Dirk van Zyl Smit (in his South African Prison Law and Practice of 1992), the British Occupation of the Cape set in place some reforms more in line with the Enlightenment view that the aim of punishment should be the changing of the offender’s mind. Hence the immediate importation of prefabricated treadmills to Cape Town and Natal. These soon went to ruin, but in the second number of The Cape of Good Hope Literary Gazette (on 21 July, 1830) it was reported that, in propitious summer weather back home at Reading Gaol, each prisoner could be made to ascend up to 13 000 feet daily. The South African colonies preferred convict stations which, by reliably supplying heavy labour, contributed more to expansion. Thus were chain gangs used to execute public works, notably constructing spectacular mountain passes into the interior. Over 1848-50 there was the famous Anti-Convict Agitation organised to prevent the British Foreign Secretary declaring the Cape another penal settlement (along with Tasmania, mainland Australia and several islands in the Caribbean), where wrongdoers from the motherland would be dumped at the colony’s expense. This movement was so successful that it had the effect of Britain curtailing its notorious transportation policy. Public executions were also abolished on British territory in 1868. By the 1870s, when the great linguist Dr Bleek needed the Bushman informants whose language and literature he was instructed to preserve, entire tribes were on hand, building that notorious Breakwater into the Atlantic, stone by chiselled stone, before dwindling into extinction.

To the traveller inspecting the old Transvaal Republic of President Kruger’s days, the prison system might have appeared rather ramshackle. The first white sentenced to imprisonment there was one Alexander Anderson in 1865, with one year including hard labour. By a special deal with the landdrost, Anderson was during that period himself to build the very tronk in which he was meant to be held. One of the most chilling stories in Bosman’s Mafeking Road collection is “The Widow”, featuring the Transvaal Republic’s first judicial execution at Potchefstroom, the place of Bosman’s early schooling. In his version, after a lengthy trial the murderer of the husband of the heroine is put to death by firing squad and buried in the yard of the courthouse. The actual event was somewhat different, being a hanging from a tree in a field outside town, where the trussed burgher made his last stand as the horses attached to the cart which supported him were geed up.

In his biography of his father-in-law Piet Prinsloo, public prosecutor of Prinsloosdorp, Sarel Erasmus records that no landdrost would go to the trouble of sentencing his black offenders, but merely flog them in the back yard himself. White suspects held before a circuit court were often perforce boarded in the local law officer’s own home. As Sarel recounts (in Prinsloo of Prinsloosdorp):

There was no gaol at Krugersdorp, and if there had been there was no money to pay a gaoler. My uncle turned a stable into a gaol, but it was only wattle and daub, and when drunken Kaffirs were inside, they fell against the walls and tumbled outside, so that there was much repairing, and the guard had to keep his rifle and hammer going all the time.

Then, one night during the great storm in this legendary tall tale, of course the entire contraption is blown away.

Sarel Erasmus is later imprisoned himself in a British gaol and, like John Bunyan before him penning his plea for grace, is destined to deliver his immortal A Burgher Quixote as his protest. In reality ‘Sarel Erasmus’ is Bosman’s predecessor, Douglas Blackburn, the journalist and satirist of Transvaal affairs. During the middle years of the 1890s, as part of his duty as the editor of his scabrous weekly newspaper, The Sentinel of Krugersdorp, Blackburn had occasion to attend executions in Pretoria: a typical note of his is “Jan, hanged for murdering Paul le Roux, died without a wriggle.” But the favourite tale of prisoners in the old Transvaal was often retold, as in this unsigned piece (called “The Gaoler of Groenfontein” in The State, July, 1911):

Those [prisoners] who were well behaved were allowed out on leave on condition that they were to be back by nightfall. On one occasion certain of them – so the story ran – had been kept too long in the village by kind friends, and when they returned to their prison home they found that the gaoler had wearied of their tarrying and had barred the gates against them: so they had to seek refuge for the night elsewhere. But with the morning light they crept back to the fold, and that day lodged with the Magistrate a formal complaint at the Gaoler’s conduct in shutting them out.

The Transvaal had erected its central penal institution at what was known as the Convent Redoubt. (Originally a military camp adjacent to the Loreto Sisters, the site later became the Royal Mint and is now the African Window museum.) As a stream ran through the property, prisoners were obliged to undertake their own laundry arrangements. Here in the garden hangings were held on Saturday mornings, open to the public as one of the capital’s few spectacles. Here old Chief Lebogo (Malaboch), the last in the line of defeated black leaders of rural resistance against the commandos, was held after the Bagananwa War and widely photographed. Over New Year, 1896, he was joined by the defeated Dr Jameson and his hundred Raiders.

But the Benthamite concept of the prison as a total institution, in which every facet of the inmate’s daily existence may be controlled until such time as he has changed his attitudes to authority, to work and to the society outside, and where the benefit of literacy training and religious instruction may be inculcated, arrives in the Transvaal only with the building of the Fort in Johannesburg (where Bosman was held while awaiting trial), and then with Pretoria Central Prison as the prime example. Described by penologists as the Pennsylvania system of prison management, it was introduced in Britain notably at Pentonville before being exported to the colonies. The blueprint allowed for single-occupancy cellular accommodation for longtimers (to prevent amorous alliances and to break up gangs), with the exercise of labour in specially designed workshops.

During the military occupation of Pretoria in the Second Anglo-Boer War, it became clear to the Governor, Lord Milner, that Pretoria too needed to join the worldwide network of formal Imperial prisons stretching, as Boer prisoners of war knew well enough, from Ceylon to St. Helena and Bermuda. The prison reserve was set aside out of town on isolated, higher ground for this purpose. By the peace of 1902 the surrounding wall was completed. In 1903 a contract for building the Central Prison itself was awarded to Johannesburg’s Brown and Cottrill, but on their bankruptcy it was taken over by Maudsley, and then by Prentice and Mackey. By 1906, at a cost of £125 000, that stone fort, the Pretoria Central Prison, was completed and ready to admit its first six hundred. It has enjoyed full occupancy ever since. And as Chapter 5 of Cold Stone Jug records, when extensions became necessary, it was the prisoners themselves who served to immure themselves in still further, each stone of their fortifications hand-dressed from their own quarry, the koppie against which they rest.

But Bosman’s Cold Stone Jug is really a critique of unthinking notions about the value of imprisonment.

The issue of prison reform went public in South Africa particularly in the days leading up to Union in 1910. The African Monthly in Grahamstown, for example, published from September, 1908, a series of articles by G. D. Gray, recommending that the future united South Africa should try and avoid the high rate of European and American criminal recidivism by genuinely affording our “broad-arrowed brethren in clanking leg-irons” the public’s sympathy and care, with the practical opportunity to learn appropriate trades and the mental skills to fit them for a decent life outside as citizens of the rising nation. Of the Transvaal’s 50 000 prisoners (the Cape had 60 000, Natal 30 000 and the Orange River Colony 10 000), Gray wrote:

After mentally and morally starving our State labourers for the required term of years, [we now also shut] every door which could admit good thoughts, keep away all that is likely to heal the diseased mind and soul – in short, empty them of good – we suddenly turn them adrift on the great evil world, and expect them to become paragons of all that is virtuous, and to live peaceful, honest, useful lives in the same society that has recently incarcerated them.

In 1910 John Galsworthy’s famous play, Justice, dramatised those same issues that troubled Gray, and many a Hollywood silent movie went on nobly to expose corruption and violence in modern gaols. In October, 1911, an unsigned article in The State on “Tragedies of the Rope” by a ‘Tolstoy admirer’ continued the bad publicity by describing gruesome executions at Pretoria Central. One was of two Australian officers in the prison yard, marched before the firing squad, blindfolded and offered a last cigarette; another of the notorious Australian, ‘One-armed Mac’ who, after a double murder committed in the Transvaal all of eighteen years before, was extradited from Australia in shackles and under escort on the Waratah, to be duly “flung violently from this world” after his missing limb.

Despite such deterrents, by the 1920s of Bosman’s term South Africa had arrived at the great social watershed that Pretoria Central Prison was built to avert, as the very nature of crime phased from amateur rural banditry to the professional and organised urban kind. Bosman’s castlist of representative characters makes this graphically clear: there is the safecracker of Chapter 2, Alec the Ponce, Snowy Fisher and Pap the full-time burglars, Huysmans the sex offender, Tex Fraser the mugger, Bluecoat Verdamp the habitual, the debonair Jimmy Gair in for financial irregularities and so on. The Nominal Roll confirms that during Bosman’s term stealing, rape and forgery and utterance were the common offences of his fellows, the vast majority of whom had British surnames. Surprisingly, the most prevalent offence was still the old bandiet one, amongst both whites and blacks, of livestock theft – to this Bosman pays no attention, possibly because their sentences were short. Nor does he feel there to be any category of ‘political prisoner’ – after the 1914 General Strike General J. C. Smuts had merely deported its Labour leaders; in 1922 Taffy Long had been hanged, but for murder rather than civil agitation. During Bosman’s term there was only one chronic escapist, and only one prisoner – presumably the original of thwarted ‘Pym’ – consigned to the Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

Reformers in the Transvaal had established with the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1909 the system of the indeterminate sentence for habitual criminals, together with the statutory body of the Board of Visitors, empowered to recommend releases to the prison Governor, as Bosman describes in Chapter 1. The change for the worse, as announced so astoundingly by the Governor to the assembled bluecoats at the end of Chapter 6, whereby indeterminate sentences were arbitrarily increased, was a setback for the reform mission and, as Bosman shows, seems to have had no meaning for the prison population.

By the mid-1940s prison reform was again an issue in the South African press: the Reverend H. P. Junod, who had served for many years as the chaplain to the segregated-off black prisoners of Pretoria Central, formed his Penal Reform League, and in 1945 the Lansdown Commission on Penal and Prison Reform was appointed. Although there is no evidence to suggest that these influenced Bosman to write Cold Stone Jug, its appearance in 1949 was nevertheless pertinent. No other writer offered the shocking testimony that all the prison system taught its inmates was stoically to endure.

And yet in Bosman’s day Pretoria Central Prison was a model institution of its kind, conscientiously managed by its Governor, Deputy Governor, Medical Officer, Head Warder, Overseer and other ranks. The Solly Flatt album, compiled in 1957 and kept at the Museum of the Department of Correctional Services in Pretoria, shows this clearly, in picture after picture. Flatt was first the prison’s Reception Clerk, then its Mess Caterer and eventually Head Warder. Between 1910 and the early 1940s he was also the official photographer, so that the mugshots of Bosman are probably his, or at least taken under his supervision. In one photo Flatt stands in his uniform and in full view behind the tripod, while his assistants – in exactly the convict garb Bosman describes – correctly keep their faces out of the lens. The tailor-shop, the printers, the brushmakers, signwriters, stonecutters and school are exactly as Bosman depicted. Even the stone quarry is captured on film, as is the Swedish drill conducted with military precision in the exercise yard.

Yet the crusade to reform Pretoria Central Prison was in full swing while Bosman was inside, thanks to Stephen Black. South Africa’s own working-class lad, Black had struggled his way up from boxing to being the country’s leading actor-manager. Diverted from showbiz to satirical journalism, he founded in Johannesburg his scarifying sheet, The Sjambok, Vol. 1, No. 1 being dated 19 April, 1929. Until March, 1931, The Sjambok would continue to appear weekly, despite mounting libel suits and other legal threats, as an alternative to the establishment’s big-sheet press and with the novelty of R. R. R. Dhlomo as a leading contributor. Only six weeks into its run – on 31 May, 1929 – Black carried a sketch called “In the Beginning” by one ‘Ben Africa’, which he must have known was a pseudonym of the young Herman Charles Bosman, forbidden to publish as he was behind bars. A feverish African liberation fantasy about Adam and Eve in an unenclosed landscape, the sketch was written in the same coyly erotic, dagga-dreamy vein as the prison poems in The Blue Princess sequence.

Then on 14 June, 1929, Black’s Sjambok began the remarkable instalments of the prison confessions of its greatest celebrity, the nation’s ‘Uncle Joe’ – the originally British actor, Lago Clifford, who from 1 July, 1924, on Radio JB had been the country’s first full-time announcer. A year before he had been consigned to Pretoria Central, an institution he fully conceded was run “on modern lines of Prison Reform.” Clifford’s series clarifies many details that are taken for granted in Cold Stone Jug: that there were three grades of prisoner (first offenders, second offenders and bluecoats – with starmen being first offenders having served more than half their sentence); the dop and drop hanging procedure; the wages earned in the workshops, rising to 3d. a day, with 30s. held in reserve to cover the cost of a coffin; and the routine by which prisoners could receive books and newspapers from outside and regular visits.

Here is Clifford’s portrait of Bosman:

The most interesting and intellectual man I met at the Central Prison was a young student – refined, creative, poetical. He is serving a sentence of ten years hard labour, having been convicted of murder, but reprieved. He is a university man who had a brilliant scholastic career; is highly read and possesses a most fascinating personality. On Sundays I used generally to chat with him. To me he was like an oasis in a desert – he freshened up the old classics – which I had practically forgotten. – We talked on Virgil, Cicero, Sallust, Homer, Ovid… In English prose and literature this man was thoroughly grounded [as well]. As we became better acquainted he lent me the copies of verses which he had written and on scanning them I realised instantly that here was no mere scribbler, such as the world is full of, but one with a rare gift…

I became very friendly with this man, but I am asked not to give his name, though what could come of this but good to the poor fellow I do not know. Will not something be done to mitigate his unhappy fate and give back to his country a fine intellect? The poor young student I speak of is an Afrikander and educated wholly in South Africa. But he has no trace whatever of any Colonial accent. His aspect is a bright and cheerful one; he has clear blue vital eyes. He was convicted of having shot and killed in an ungovernable fit of rage and jealousy. There was not any suggestion of a premeditated crime; it was wholly a crime of passion, of impulse. The law recognised this when it reprieved him; but ten years is a cruel sentence. The young man has undoubtedly great literary gifts, some think genius. And there he lies, wasting his life and abilities, which could be used in the service of his beloved South Africa…

To me it seems wrong to destroy a brilliant talent – or to stunt it in these dreadful surroundings… Above all the young prisoner is a philosopher and he makes the lightest of the thorny path which fate has mapped out for him… When I first arrived he was one of the assistant librarians – but after some months of this indoor work he asked for a change of labour, asked to be allowed to break stones! But the stones (as he said) were “under God’s clear sky!”

Now he is in the Carpenter’s Shop.

Among the First Offenders the personality and good temper of the young prisoner have made him very popular and I do not think he has an enemy in the prison.

As evidence of this youth’s potential, on 5 July Clifford had Black quote his lyric, “Perhaps Some Day”, which begins:

Some day, perhaps, I’ll see the world again.

May be some day.

When all those things of grinding grief and pain

Have passed away.

For there’s a longing in my heart to be

Beneath wide skies…

Twenty years later Bosman would weave that phrase, “some day”, into the vast pattern of his book (see Chapters 8 and 9 here).

In accordance with Black’s policy on the paper, the thrust of Clifford’s series was against capital punishment; indeed, at the Judges’ Conference held in Cape Town in January, 1931, its abolition was discussed as the key topic. Black kept pushing on this issue: on 23 January he ran a hair-raising piece by an unidentified ‘legal reporter’, obviously an official in the Justice Department, on “When Murderers Face Death”, which painted South Africa’s places of hanging (then in Cape Town and East London, Pietermaritzburg, Bloemfontein and especially Pretoria, before they were all centralised in the latter) as vile butcher’s shops.

Another ex-con to hit town was the forger Aegidius Jean Blignaut who, as a more cultural half-section to The Sjambok, in December, 1929, launched Vol. 1, No. 1 of The Touleier along the lines of Roy Campbell and William Plomer’s Voorslag (of 1926 in Durban). On the masthead was the synthetic name of ‘Herman Malan’ as literary editor, responsible for the authorship of some of Blignaut’s more inflammatory exposés and also for any further work smuggled out from his old university crony, Bosman. Here the latter’s masterly story, “Makapan’s Caves”, and other now classic pieces, first saw the light, mixed in with much other dubious and substandard material. Black continued to use Bosman in his magazine’s column under the rubric of ‘Life as Revealed by Fiction’ – for example, on 2 January, 1931, he carried “In Church” by the Bosman half of Herman Malan, and on 13 February “The Night-dress”, both accomplished pieces.

When Black’s Sjambok had to close, Blignaut immediately took up the baton, reviving Black’s old LSD as The New LSD on 27 March, 1931, without missing a week, and by July converting it into New Sjambok. (Black was to die unexpectedly on 8 August.) There Blignaut also continued the prison reform campaign with several of his own scurrilous and reprehensible pieces (which he was often to recycle). Examples are “What God and the Hangman Know” (on 25 July, 1931), which sentimentalises a gruesome adieu, and “Van Straaten – Prison Teacher” (on 7 September, 1931), which purports to expose the farce of Pretoria’s prison school.

Only one of these New Sjambok japes may with certainty be attributed to Bosman, on the grounds that it was repeated practically verbatim in Cold Stone Jug (the account of Billy the Bastard searching the convict from the sawmill missing two fingers in Chapter 5). This item was presented as “From our Correspondent” in Pretoria Central Prison no less, and headed “Morons in Khaki” (on 12 October, 1931). It concludes rather ruefully:

life is tolerable [here] only because most of the warders and chief warders are humane enough to exercise a certain amount of discretion in applying the Prison Regulations.

The piece also mentions his discovery of his brother convict-writers in the prison library, Paul Verlaine and Oscar Wilde, together with François Villon, whom he would for ever after cite as his true soul mates. Villon of course earns the final accolade in the Epilogue of Cold Stone Jug.

Later the Blignaut-Bosman team descended to using their Ringhals and New Ringhals to conduct vicious scams of minimal literary worth. Bosman kept writing stories of interest (“The Prophet” first appeared on 20 January, 1934, in the only copy of The Ringhals which has survived), while Blignaut was the next, disguised as the ex-clergyman ‘Clewin Webb’, to write his rather disjointed prison memoirs. In the episode of 24 November, 1934, he recounts how when he had come across Bosman once again in Pretoria Central in 1928, he “looked less like a murderer than usual. Perhaps because his crime was due more to impulse than premeditation he did not seem to have stamped upon his features the brand of Cain.”

The evidence led against the effectiveness of the prison system by the three gaol-birds, Clifford, Blignaut and Bosman, may be summarised on two fronts. They stood not only against what was becoming the Right’s definition of the problem of crime, but also against the Left’s explanation. Under the first count they could evoke a long history of what may be labelled eugenicist thought, beloved of white male supremacists and predicated on a hereditarian belief which attributes criminality to bad genes. In the late 1920s much public debate in South Africa was tinged with the fear of degeneration which the race biologists predicted in reaction to the rise of women’s rights and increasing sexual tolerance. For example, take Dr C. Louis Leipoldt, the great poet and the Transvaal’s first medical inspector of schools, who was now the editor of The South African Medical Journal in Cape Town and who should have known better. On 21 July, 1931, he began a frank series on “Racial Deterioration in the Union” in Johannesburg’s Rand Daily Mail explaining the nation’s drastic need to deflect a future of flat-footed halfwits and mental defectives. In response Blignaut went off the deep end (on 25 July in The New Sjambok), inviting Leipoldt to examine their muscular, eleventh-generation office boy, who would show him just how degenerate he had become by rolling up his sleeves and hurling the “flat-brained pseudo-poet” down the New Sjambok’s stairs. When a Transvaal judge recommended sterilisation as a solution to a mere bigamy case, Blignaut was incensed. Bosman’s own riposte to this line was to be Cold Stone Jug: its firm, orderly intelligence dispels any impulse to explain away the criminal mind as biologically handicapped.

Nor had the three ex-cons time for the contrasting view on the Left (and Bosman as a university student had made trouble as a Young Communist), that crime, far from being determined by evolution, may be attributed to poverty and other flaws inherent in the capitalist order. This theory had its origin in middle-class Victorian theological panics about the seething underworld of the very underclass their market economy was creating. Even The New Sjambok’s proprietor, gentlemanly John Webb, wrote (on 25 July, 1931) that the cause of crime was nothing other than “being poor, and not having sufficient influence to have the law interpreted favourably.” Yet in Clifford’s, Blignaut’s and Bosman’s records there is no sign of any feeling of victimhood owing to some lousy, disadvantaged past. Remember that Cold Stone Jug is the story of a lot of innocent men, free agents all, until they inexplicably become unfree.

When Bosman was discharged from Pretoria Central Prison, he could no longer work as a teacher. Taking over as ‘Herman Malan’ the poet on The New Sjambok, he could strike off in a new direction. With the trial in 1932 of Mrs Daisy de Melker, the opportunity arose for him to use his inside knowledge of prison life to catch pennies. She was charged with poisoning her husbands and her son in order to claim the benefits of their insurance policies. De Melker’s petition to the Governor-General for clemency, handwritten childishly in pencil, is still on file at Pretoria Central; there she asked him to believe she had purchased all that arsenic to kill the cats… Once her appeal had failed, Bosman hit the streets with two sensational pamphlets, detailing expertly how she was to be strung up.

Soon Bosman met Ella Manson, at the reference desk of the Johannesburg Public Library, soon they were married. Wisely they departed to make a new life in London. There in 1936 – while working again for John Webb, who had now founded The Sunday Critic – Bosman made another attempt to put his prison period to some use. The upshot was a serial running to 15 000 words entitled Leader of Gunmen. It begins on 19 April with the following summary:

Parts of it read like fiction… The master-mind who built up an organisation of gunmen; he inspired them with his own recklessness and his own desperate courage; and then he flung them against society… Crime-wave upon shattering crime-wave… They terrorised a nation; members of the police force got scared and resigned; even the local judges wavered, so a judge was specially imported from another Province to try them – Judge Gregorowski, who had sentenced the Jameson Raiders to death a quarter of a century before…

A gang leader who saw his followers go one by one to their doom; they were hanged; they were shot; they passed behind prison-bars with life-sentences; their reason gave way and they were flung into asylums; or they died by their own hand…

But their leader was not vanquished: undeterred, he set about creating another organisation… a motley assortment of embezzlers, murderers, burglars, sneak-thieves, pimps, killers; he knit them together with a cold purposefulness and a grim energy that was almost Napoleonic in its quality – a wild and inchoate Napoleon, who thought on criminal lines and talked in prison slang… And the first instalment begins now.

The titles of some of the thirteen episodes of Leader of Gunmen give an indication of how the serial developed: “Chief of Police Arrested”, “Claude Satang Double-crossed by City Councillor”, “World’s Toughest Killer Talks”, “Most Sensational Escape in Crime Annals”, “Town at Gunman’s Mercy”…

Here is a sample of the serial’s bluff, jocular style:

Bishop was sitting in a prison-cell brooding over many wrongs. His cell mate was a rather superior young Englishman who had not been long in South Africa. (But he had been there long enough to find his way into Central Prison.)

“Yus,” Bishop announced sombrely, “I am what you call an eaten man.”

“How interesting,” his cell mate exclaimed. “I, too, am a public schoolboy. Eton, are you? What year?”

“Yus, it’s my year, all right,” Bishop answered. “My left year.”

Leader of Gunmen was Bosman’s first try at wrapping a history of South African violent crime into an entertaining package. Aimed at timid British readers, its tone was perhaps too bullying and insufficiently beguiling for it to succeed. By 5 July its publication was suspended.

Yet its hero is an interesting figure. He begins as a sergeant scouting for Smuts during the First World War,

not appearing in any way different from any of the thousands of young soldiers who had been drafted to East Africa. His ambitions were the ambitions of hosts of other normal young men of his age. He certainly had no dreams of one day becoming a gangster.

He was captured in 1917, escaped along with two other men. They passed through terrible hardships. Two of them died. The survivor was Claude Satang. He was tougher than his companions. But, when the South African troops found him, they had to identify him by his badge. He had lost his memory. So he was sent back to South Africa. Gradually, in the hospital at Roberts Heights, near Pretoria, Claude Satang’s memory returned. But with it there came also the frightening knowledge that his outlook on life had altered. He no longer had his casual and easy-going acceptance of things as he found them. In its place was a bitter and unreasoning hatred of society.

He did not understand it at first – this change that had come over him. Later, he understood only too clearly. But then he was in a prison-cell… Before him lay the years of the sentence he had to serve. Behind him was the most stupendous and incredible career of crime that the world had ever known… (Don’t miss next week’s instalment.)

Rather like the bluecoat’s tale in Chapter 2 in Cold Stone Jug, Leader of Gunmen concludes in the air, starting “just from anywhere and ending up nowhere.” From what may be pieced together of it in the Colindale Newspaper Library, it is of the same type as other works in that extraordinary rash of prison fiction Bosman mentions in Chapter 8 here, with titles like Ruined Through Being Too Kind-hearted and so on, through to Cold Stone Jug itself.

The Museum of the Correctional Services Department holds an actual copy of one of these, produced by Bosman’s own publisher, APB, in the same year as the final Cold Stone Jug. This is a South African classic of its kind, Christoffel Lessing’s treasury of prison lore called Kersfees in die Tronk (1949). Lessing had been inside for theft since 1928, and in Pretoria Central since 1933 where he managed to pass from Standard Six to a Bachelor of Arts. As Bosman was to do, he turned to Die Ruiter and to Die Brandwag for publication.

Like Bosman in Cold Stone Jug, Lessing in his Kersfees gives no details of his crime, nor does he repent. The hangings high on brandy, initiations in the star-yard, the scenes in the stone-yard with 6 lbs. hammers, the monthly concerts and boxing tournaments organised by the inmates, the whole establishment singing “Sarie Marais” together on Christmas Eve, Beauty Bell the safecracker and threepence a day… these are the highlights of the South African prison novel of the period. Lessing goes one further than Bosman, however; at least half of Kersfees is devoted to fantastic tales of breaks which every convict except Lessing seems to have pulled off. Kersfees is a rather more genial version of Cold Stone Jug, done in the raw. David Goldblatt the photographer has filled in the rest of Lessing’s biography (in the Stet of May, 1986), including a reading of his later English-language autobiography of 1950, Forth from the Dungeon. Lessing himself has reappeared (in the Stet of November, 1988), with a poignant memoir on the theme that could well have been Bosman’s own: that it is only on his release from prison that the ex-con’s punishment really begins.

At all events, Bosman in London wriggled out of providing a denouement for Leader of Gunmen, his objectionable first effort, with the following announcement (on 12 July):

We regret to inform our readers that we are discontinuing our very popular prison serial, owing to the constant criticism that is being levelled at certain stark features of the story. The Sunday Critic was not actuated by any spirit of sensationalism in publishing a description, for instance, of the manner in which a convict ate a portion of his live cell mate.

It is our sincere hope that, by drawing public attention to the debasing effects that prison life has on the strongest mind, we would be able to exercise a powerful influence in the direction of prison reform.

We therefore leave Claude Satang and his fellow-gunman, Dirk Joubert, in the African Bush. We leave them still uncaptured. We bid farewell to Cloete and Babyface de Klerk and Alec the Ponce. We depart from these stern characters, in the evening, when the dusk is falling over the grim walls of Pretoria Central Prison, and in the cells the cigarettes are being lit, and the hashish ‘smoke’ is being passed around.

Fratres, valete.

With that poignant salute, Bosman leaves off trying to make something of his prison experience. It would take him more than a decade before he was able to face it again, this time in the last part of his novel, Jacaranda in the Night, where his protagonist serves a stint on the stone-pile in Pretoria Central, and then in the manageable and mature form of the present book.

What works did Bosman read to sharpen his concept of the ‘prison memoir’?

In Cold Stone Jug he mentions as familiar from his childhood Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, with its fearful entombment in the dungeon of France’s Robben Island, the Chateau d’If off Marseilles (although he remembers it more for its presentation of hashish-smoking). He would surely also have known of Victor Hugo’s ticket-of-leave man, Jean Valjean, in Les Misérables (“Once I stole a loaf of bread to stay alive, but now I cannot steal a name to go on living”). Hugo himself had popularised the European prison reform movement in his remarkable Prison Writings of the 1830s, particularly about Paris’s La Roquette (“The inmates teach me to talk in their slang… getting hitched to a widow… treading the boards… getting the swing of things… showing me the ropes…”; “the scaffold is the only construction that revolutions do not demolish”). Bosman seems not to have read Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the House of the Dead (1860), about his four-year term in Siberia, although the Constance Garnett translation into English became available during his teens and on 7 March, 1930, Stephen Black in The Sjambok had attempted to revive interest in it by nominating it as one of his monthly Neglected Masterpieces. Yet Dostoyevsky set the trend in novelising the modern prison experience by using a faceless narrator reporting on the lives of his fellow convicts, unrepentant all (“Man is a creature that can get used to anything, and I think that that is the best definition of him”). Nor does Bosman seem to have made use of the Johannesburg Public Library’s copies of these other classics in the genre, which Ella Manson could readily have made available to him from the reference section: the historical novel on which the literature of sister-colony Australia was to be founded, Marcus Clarke’s For the Term of his Natural Life (1874), about the British Poe-reading Bohemian transported to the antipodes with a 16-inch sleeping space per convict on board; the early Victorians like Charles Reade who describe the inside of houses of correction; and the Irish nationalist leader, John Mitchel, whose Jail Journal (1854) includes an account of his year marooned on a prison ship in False Bay during that famous Anti-Convict Agitation.

However, two of JPL’s well-thumbed volumes did certainly have a bearing on the writing of Cold Stone Jug. The first one Bosman acknowledges having as part of his weekend reading (in his Pavement Patter column, “The Innocents Abroad”, Trek, November, 1948): a book recording “a brief time of recess from the daily grind”, Silvio Pellico’s Ten Years in Prison. But what Bosman had in hand was a now untraceable typescript of a translation of it into Afrikaans, which he was presumably to vet for publication. (JPL holds several editions of Pellico in English, with one into French, as well as the original Italian of 1831.) Once as famous as his contemporary, the Marquis de Sade, Pellico was the romantic poet and patriot sentenced to death for treason under the Austrian Occupation, whose sentence was commuted to fifteen years of gruelling servitude. A year after reading Pellico, Bosman had completed his own prison memoir.

The second influence, although there is only circumstantial evidence for this, is the work of one Jim Phelan, now also largely forgotten. Judging by the copies of Phelan’s various works held in JPL, there was quite a vogue for him in Johannesburg in the 1940s. Bernard Sachs, Bosman’s editor at The South African Opinion and Trek, remarks in the first of no less than four memorials he wrote of his old schoolmate and colleague that “Cold Stone Jug, a description of Bosman’s life in prison, is competent, but has been done as well by Jim Phelan and others” (Trek, November, 1951), as if the Phelan connection were common knowledge. Once Bosman was safely dead, of course Sachs was free to retell his early life-story as he saw it in a thinly veiled, rather tasteless novel which includes extensive quotations from the 1926 trial records (The Utmost Sail, 1955).

Phelan was born near Dublin in 1895; at the time Bosman would have read him, he was a bestselling author, famous for his recounting of his thirteen years spent from 1926 in Manchester Gaol, Maidstone, Dartmoor and Pankhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight, serving his term for murder. He too consoled himself with the writings of his fellow “healthy dead men”, Bunyan, Hugo, Wilde and Henry, and could turn a black epigram (“in the condemned cell the only statistic of importance is one’s weight (lbs.)”). In his Jail Journey of 1941 he remarks: “I do but record the strange things I saw in that country I visited.” He sets the precedent for recounting parts of his story in the secret language of that country, as Bosman would do as well.

Bosman was also conversant with how the Americans handled his subject matter. There was Ambrose Bierce’s exemplary horror story about an execution, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” (collected in his In the Midst of Life in 1891), in which the Southern planter and spy caught by Union soldiers sabotaging the railway bridge over Alabama’s Owl Creek is trussed up over the raging stream with his neck “in the hemp.” Bosman’s other favourite, O. Henry, left at his death an unfinished story called “The Dream”, about a man awaiting execution.

Yet by as late as 1947 it seems that our ‘Herman Malan’ had so successfully made himself over as ‘Herman Charles Bosman’ that his criminal past no longer existed for him. Consider this excerpt (from his Indaba column that July), written in his new chaffing manner, appropriate to the sort of ephemeral bantering in which he excelled. Is there any detail here to give away the fact that the reformed Bosman really knew what he was talking about?

[What] struck me in connection with the difference between Cape Town and Johannesburg relates to all the talk that is going on locally about the projected closing down of the Roeland Street Gaol. I am, naturally, not acquainted with Roeland Street Gaol: I am a Johannesburg man. But it would appear that this far-famed Cape Town prison has got just as much character, individuality, squalor, disagreeableness and romance as, say, the Johannesburg Fort. Now, it is when one places the Fort in juxtaposition to Roeland Street that it would seem (to the person inside trying to look out) that Cape Town is not, after all, a thousand miles from Johannesburg…

Incidentally, it would be interesting to know why it is that certain prisons have developed a definite individuality, so that the sound of their names means something: Dartmoor, Sing-Sing, Alcatraz, San Quentin, the Breakwater. About these names there is a solid and eminently satisfactory grimness. Whereas, the names of lots of other prisons – and the world is full of prisons – evoke, by comparison, hardly any kind of emotional response.

Next to Roeland Street and The Fort, Pretoria Prison sounds colourless and insipid, almost just like being inside. And I wonder why that is. After all, has the Pretoria Gaol not got just as thick walls and just as heavy bars and just as small window-apertures? – and are the warders not just as brutal and burly and the convicts as debased and sullen and hang-dog looking as their fellows in Roeland Street? And yet look at the difference in the sound of these two gaols in respect of tone, shuddery reaction and general showiness.

Anyway, I think it is a pity that prisons with so much individuality and tradition as The Fort and Roeland Street must go. But the authorities will no doubt try and replace them with gaols just as good. (And succeed.)

His friends of the late 1940s, Gordon and Yvonne Vorster, used to recount that when Cold Stone Jug first came out they were completely taken aback: they had not known anything of the author’s shady past. They knew that it had been his habit regularly to retire into a room the size of a toilet, with a table and chair and with a goodly supply of typing paper, and to emerge from there cordially enough when his daily stint was done. This cubbyhole of his was no ordinary retreat: adjacent to the lift shaft of His Majesty’s Buildings in Eloff Street, it had once served as the walk-in safe of The South African Jewish Times. Its editor, Leon Feldberg, had provided him with the requisite keys to lock himself in and even had a small window knocked into the wall. Claustrophobic, reliving his captivity, there Bosman used to write until all his drafts were complete. Not wanting to pry, the Vorsters had never quizzed him about the contents of the work. Even his wife of the time, their confidante Helena, admitted that she was shocked by Cold Stone Jug, albeit pleased that he had been able to face those ghosts and write them out, she hoped once and for all.

The reception accorded Cold Stone Jug in the Johannesburg English-language press at first was edgy. Bosman’s friend and champion, Mary Morison Webster, the Georgian lady poet who could set the trend for the nation on The Sunday Times, sat this one out. For weeks Bosman had to watch the space other competing volumes in the bookshops were accorded: Madeleine Masson’s new biography of Lady Anne Barnard; the entire page two filled week after week with excerpts from Winston Churchill’s war memoirs; how members of Mrs Mackie-Niven’s safari party had at last traced the huge wild fig-tree just over the Mozambique border where her father’s immortal dog, Jock of the Bushveld, lay buried.

In the event, The Star led. Its brief review in its weekly space on 31 January, 1949, was entitled “Tale of Prison Life.” This was alongside a longer column devoted to the problems the erstwhile prison reformer Alan Paton was having answering his continuing fanmail over Cry, the Beloved Country, and the news that the satire about the stock exchange, Kaffirs are Lively, by Bosman’s colleague on Trek, Oliver Walker, was still doing well. The record run of Leonard Schach’s production of The Glass Menagerie was also cause for affirmative comment. The entire facing page was devoted to Lyndall Greig, niece of Olive Schreiner, with the first release of her sprightly memoir of their tour together to Rhodesia long before.

The Cold Stone Jug review is unsigned and concludes:

There are many unpleasant and grotesque subjects offered for the reader’s contemplation. The subject matter of criminal character and prison atmosphere have been truthfully recorded. But in this generation we have become familiar with grim themes. The quality that lifts this book out of such a context is its humour, objectivity and a style that is full of nuances of meaning, implications that slide into the mind in the by-going. This may not be everyone’s book, but it is an interesting one.

Over the following weeks The Star kept listing Cold Stone Jug as a ‘Book in Demand (non-fiction).’ Yet, as if to neutralise any bad reports on prisons, on 26 February it devoted a full page to the new British system of prison farm-labour, “From Pentonville to a Prison without Bars.” This included a detailed report of the new spirit in which the High Commissioner, Mr Goodenough, voluntarily gave his talk to those inmates left in Pentonville; his topic was Southern Rhodesia’s progress towards dominion status. The occasion was concluded with Goodenough’s favourite wild animal stories.

Three weeks later Charles Eglington came out with the lead review in The Rand Daily Mail (“Prison Walls” on 19 February). Doubtless distressed by its lurid pulp fiction cover, Eglington found the work full of “unfortunate blemishes”: repetitive, aimlessly rambling and gratuitously sordid. He concluded rather cussedly that, in his view, Bosman seemed “not to want to evoke compassion in the reader and that the humour is so often, if not cruel, then callous.”

On the next day The Sunday Times at last noticed the work, though it also kept its distance. The reviewer, identified only as ‘S’, conceded it was:

true to life and well written.

The characters are well-drawn and living, and if they seem all to be touched with the same primitive rawness, it is probably not to be wondered at when the walls and bars of a prison carry their own inevitable and characteristic prison smell in spite of all the scrubbing. The book is vital and interesting but tough, like its subject.

The space opposite was devoted to major coverage of yet another book devoted to soil erosion in the Karoo.

In the March, 1949, number of Trek another of his colleagues there, Joseph Sachs, attempted to grapple with “this sinister drama of human degradation”, noting that such material was hardly the occasion for the usual literary moralising. But halfway through he simply gives up, resorting to lengthy quotation without further comment.

The first printing of Cold Stone Jug did well nevertheless, selling out within seven months. With reprinting it continued to sell: for July-December, 1949, Bosman’s royalties were 16/2; for January-June, 1950, £2/6/9; for the rest of the year, £1/5/2; and for the first half of 1951, again £2/6/9…

But the climb of Cold Stone Jug to some status in the critical hierarchy was slow. In 1951 the official organ of the Mineworkers’ Union, the weekly bilingual paper Die Mynwerker/The Mineworker, launched its literary supplement called Excelsior, which serialised complete books. Bosman had the gratification of seeing his Cold Stone Jug “unconditionally declared a masterpiece” and relaunched there on 15 June; between episodes 18 and 19 he unexpectedly died, and Excelsior carried a heartfelt obituary for a fellow worker. The serialisation continued to its bitter end on 1 February, 1952.

In his survey of fiction in English from Union to 1960 (in the PEN Annual of that year), Edgar Bernstein did place Bosman in “a class of his own”, describing Cold Stone Jug admiringly as an “autobiographical novel” (“I know of few stories which plumb deeper into the emotions of prisoners”). A decade later, in an article in the New Statesman (on 23 January, 1971) focusing on that other Afrikaner son of the soil, Eugène Marais, Doris Lessing digressed to include Bosman:

Marais was a solitary, but one of a scattered band of South Africans bred out of the veld, self-hewn, in advance of their time – and paying heavily for it. Schreiner was one, always fighting, always ill; Bosman another, the journalist and short-story writer who wrote the saddest of all prison books, Cold Stone Jug. His account of how hundreds of prisoners howled like dogs or hyenas through their bars at the full moon – everyone, warders too, pretending afterwards that it had never happened – has the same ring to it as Marais’s description of the baboons screaming out their helplessness through the night after leopards had carried off one of their troop.

With an appreciation like that, Cold Stone Jug may at last be seen as having come into its own.

When contemporary scholars attempt to describe the now substantial sub-section of South African writing designated as ‘prison literature’, Cold Stone Jug is usually mentioned as the foundational text. But we approach Bosman’s 1920s across the divide of the apartheid period, overlaid with new meanings for even the basic terms of punishment. The transitional moment is hard to pinpoint. But, for example, there is Hannah Stanton in her account, “Pretoria Central Gaol, 1960” (in Africa South in Exile, October-December, 1960), where she records that after the declaration of the State of Emergency of 30 March, 1960, she was detained there with some 1 900 others, without any charge or access to her co-workers at the Anglican Tumelong Mission in Pretoria’s Lady Selborne, before being deported as a British citizen. Her description of the prison routines might have come directly out of the pages of Bosman, even though the nature of the offence has changed, together with attitudes towards it. She is no longer a ‘criminal’: she is a ‘political’, with all that that has come to mean.

In a review-article in the October, 1975, issue of The Journal of Southern African Studies C. J. Driver was the first to link Cold Stone Jug to the new school of prison writers (including Albie Sachs, Daniel Mdluli aka D. M. Zwelonke and others). Neil Rusch (in an article in the Speak of Autumn, 1979) tries devotedly to use Cold Stone Jug as his key text in recounting what he terms the subsequent Prison Reform Crusade to lift restrictions on reporting of prison conditions within the new gulag of the apartheid state. Sheila Roberts (in Ariel of April, 1985) is one of the first to isolate ‘prison literature’ as a distinct category of South African culture. Situating Cold Stone Jug as its origin, she deals with the poetry of Dennis Brutus (Letters to Martha), Breyten Breytenbach and Jeremy Cronin (Inside), commenting rather unsurprisingly on the sameness of the experience expressed (prison is prison, as she remarks). Cronin himself in 1985, by contrast, wrote about how uncomfortable he felt being lumped together with the unregenerate lag. By the time of the article on writing from South African prisons by Anthony D. Cavaluzzi (carried in the Wasafiri of October, 1990), this sub-set in the literature has become widely known as typical of a new African experience of oppression, that of the ‘exile within.’

In a paper delivered at the Association of University English Teachers of Southern Africa conference held in Stellenbosch in July, 1990 (and published in the ninth English Academy Review), Mitzi Andersen suggested that Cold Stone Jug, being organised like a novel, was in fact considerably fictionalised. Pointing to Bernard Sachs’s evidence, she showed the originals of some of its characters to have been substantially altered – one Ronald Stewart, a British actor who once he was out never shaved, became ‘Slangvel’; an Andrew MacGregor was turned into the backveld schoolmaster, ‘Huysmans’, but in real life had actually married his under-age poppet, Kate, before eventually murdering her; ‘Tex Fraser’ was really nicknamed the Yank before he was released from the nick; the long monologue at the end of Chapter 2 was the speciality of a certain Jeff, who at last escaped the indeterminate sentence to reunite and party with Bosman in the back room of The Sjambok printing works. Another attempt to pin down the exact genre of Cold Stone Jug is Henrietta Mondry’s (in the Journal of Literary Studies of June, 1992), and in the English Academy Review of the same year Margaret Lenta persuasively argues off those who have disqualified Cold Stone Jug from being a major South African creative achievement because of its mixed-genre nature.

Then David Schalkwyk (in Research in African Literatures of Spring, 1994) takes Roberts’s grouping further, including many other writers who have endured prison to leave an account of it (Ruth First, Mongane Serote, Molefe Pheto in And Night Fell, Hugh Lewin) in various based-on-fact ways. As for Bosman, their interest lies in their canny use of irony as a coping device; a grand school of surviving, indeed. More recently Anthony Holiday (in Leadership during 1998), who also has done time in Pretoria’s condemned cells, while commenting on the new ANC-governed South Africa’s scrapping of the death penalty, has taken the anti-capital punishment campaign into Africa at large.

Few critics of Bosman in the context of prison literature, however, link him up to the tradition in which he placed himself, that is of European writing on the topic from St. Paul onwards. Nor are they often able to handle the fact that, unlike the politicals, always assumed to be unjustly punished, Bosman was indeed a common criminal owning up to his guilt.

Also overlooked is his scathing indictment of the system of capital punishment, made imaginatively in Cold Stone Jug when the story of his Stoffels (stof = dust in Afrikaans) gets underway and elsewhere. None make the obvious comparisons with E. E. Cummings’s The Enormous Room of 1922, or with George Orwell’s opinion about “the unspeakable wrongness of cutting a life short when it is in full tide” (in his essay of 1931, “A Hanging”); with Arthur Koestler’s 1955 campaign against what he called “the monthly sacrifice” in Britain, where once upon a time under the Bloody Code there were 220 offences for which suspension at Tyburn tree was the remedy and even unruly horses were hung for throwing their riders; or with Albert Camus’s 1957 diatribe against what he termed the law of retaliation in his “Reflections on the Guillotine.”

The imaginative responses of writers who have not been prisoners are also neglected. Just one example is Nomavenda Mathiane in her magnificent report (in the Frontline of April-May, 1988), bidding farewell to those on Death Row in Pretoria Central Prison. Nor until Zackie Achmat’s article exposing the prevalence of forced homosexual liaisons between older and younger prisoners (in Social Dynamics in 1993) would Bosman’s important theme – his terror of protection turning into tampering – be addressed with any academic seriousness.

In an article in the Natalia of 1997, Adrian Koopman and his students put Cold Stone Jug to yet another use as a touchstone when interpreting the graffiti found on the walls of the old Prince Alfred Street prison in Pietermaritzburg when it was decommissioned by the Department of Correctional Services in 1993. The scene of terrible floggings on the blood-spattered triangle – as Blackburn recorded in his indictment of the way crime was controlled in colonial Natal, the novel Leaven of 1908 – Pietermaritzburg gaol had hosted many a hanging as well. Against the authorities, Koopman maintains, the anonymous scratchings on the walls – particularly of guns, calendars, crooked cops and the inevitable sexual parts – represent a poignant expression of resistance against the anonymity forced on all prisoners of the old type: those who used boob-slang and left no other record behind.

A concluding note on prison argot.

In one of his columns for The South African Opinion (in June, 1946) Bosman recounted that that brilliant trawler of bawdry and illicit lingo, the New Zealand-born scholar Eric Partridge, had now cast his net over South Africa, inviting local experts to dish him their verbal dirt. Bosman responded with relish; the time had come to print South Africa’s unprintable. He offered these credentials:

I have been afforded exceptional facilities for studying South African prison slang at first hand, and rather extensively. And I believe that in this tarnished word-currency, which starkly illumines the mode of life of a little-known and rather terrible world, we have something that comes very near to the earthy side of real poetry. It is something that has genuine literary significance: the fact that a few rough and sullied words can lay bare the whole inner life of a criminal, and make a prison up in a moment, with its gates and walls and warders, in sunshine and in shadow.

His article, called “South African Slang”, stresses the contributions of Afrikaans and black languages to the basic convict vocabulary, otherwise derived mostly from the East End of London, District Six and Fordsburg. He reckoned that a unique strain in that “great clearing-house of crime, Pretoria Central”, had been colloquialisms from its Australian gangsters (bonzer for deserving admiration, bosker for good and swagman as in tramp), the original core of informants having been dropped into silence long since. Many of the items he cites are so confidential to prisoners that he seems eventually to have weeded them out of the final Cold Stone Jug six months later, the text making only elementary explanations as it proceeds.

Here is Bosman’s beginner’s list, as explained from the end of Chapter 2 onwards:

blue – high; bluecoats – habitual criminals; boob (rather than the common British jug or stone jug, originally referring to Newgate two centuries before, or the American cooler, slammer or pen for penitentiary) – prison; boom (also American green leaf or Navy cut, ashes, grass, the herb, Nellie, papegaai, queer stuff, the weed) – dagga; bottle, lumber – smuggle; bunk – observation cell; channel – distributor of contraband; china (plate) – mate (riming slang); crook – no good; daisies – shoes; do one’s dash – give up; a doppie of tobacco ration, a stoppie of dagga; drop – get convicted; edge that – cool it; go in smoke – into hiding; head – long-term prisoner, not yet a lifer; hook, also crook or onkus – difficult; the hug – ambushing a victim from behind; jack – backside; jerry – to tumble to; john – policeman; johnny (horner) – corner; lam – on the run; leaves – banknotes; longstall – keep cave; lumber, nab, pinch – arrest; moll – woman; nark on – report; peter – cell; pipe – to spot; poke – smuggled goods; pom-pom – discharge suit; ponce – pimp, procurer, brothelkeeper, whore-monger; pozzy – hideout; rammies – trousers; rep – prison record; rookers – dagga smokers; roomer – method of waylaying; sandbagging – cosh and mug; sassing – harassing; scandal, skinder – to gossip; screw – turnkey, warder; shelf – traitor; snout – a kick, also tobacco; soup – dynamite; span – team; stone balmy – absolutely insane; swinging the lead – pulling a trick; zol – hand-rolled smoke.

The above vocabulary constitutes the core of what a later inmate (in his article, “South African Gaol Argot”, in the UNISA journal, English Usage in Southern Africa of May, 1974) defines as ‘Central English’, evidently still petrified there. The unidentified linguist lists as current all the syntactical features which Bosman used in his recorded speech: the double negative (I haven’t got nothing); the misuse of parts of speech (Do it good); the dropped auxiliaries (I done it) and prepositions (Don’t swear me), with the historic present tense used to such vivid effect (So I says to the Bombardier… ). Those familiar with Alex la Guma’s prison stories of the early 1960s will readily recognise those features, together with much of that persistent “tarnished word-currency” (burg, john, juba, rooker, squashies), still largely uncaptured in Oxford’s 1996 Dictionary of South African English on Historical Principles.

Much of this carceral parlance Bosman already knew from his reading of turn-of-the-century O. Henry. He used terms like box-man and cracksman (safecracker), to be buncoed (taken for a ride), graft and spiel (scam). More than once he described the bull-pen, the admissions part of the stir (prison). To him lamb meant a predator’s under-age (female) sex partner (see Huysmans’s twelve-year-old in Chapter 4), while punk meant the ambiguous male equivalent (the pansy’s rabbit is Pym’s expression).

Entrance to Pretoria Central Prison, Klawer Street (photo: Craig MacKenzie)

A scene from the Solly Flatt Album, of the Pretoria Prison, late 1920s

A-2 Section entrance

A-2 Section

Quarry

Print-shop

Brush-shop

Scenes from the Solly Flatt album, inside Pretoria Prison, late 1920s

Once the Penguin New Writing volumes had first made vulgar Commonwealth fiction of interest to London while Bosman was there before the war, a writer like Frank Sargeson could splash around these terms, apparently in common use in New Zealand (in his memoir, “That Summer”): cobber; going crook; dees (detectives); dinkum lags; john; peter; possie (vantage point) and screw.

And for the sake of comparison here is a checklist compiled from Phelan’s Jail Journey as the basic phrasebook of his Home institutions. Almost all of it correlates with Bosman’s:

bitches bastard – bad screw; china; chokey (solitary punishment cell); compound (open working area); dip – pickpocket; graft – to cadge gifts with a hard luck story; grass – spy who betrays fellows to warders; the mix – to enlist a warder to make trouble for another convict; mugs – older inmates; plant – hiding place; popper – one in for shooting; red-collar – freedom to go about unsupervised; screw; screwsman – thief; snout; stiff – illicit note from one convict to another; stir; straighten – get someone to do you a favour; swagging a kangar (kangaroo, chew) – carrying a bit of tobacco; tan – club and kick to a standstill; work a ticket – get a transfer; turnover – cell search; wideman – professional robber.

As in Bosman, much of Phelan is given over to the rituals of tinder-boxing and all the argot associated with tobacco as legal tender.

Both writers also remark that, in their experience, the rule of perpetual silence among convicts had only recently been lifted in the prison system of the English-speaking world. In other words boob-slang as they learnt it had previously been only an illegal side-of-the-mouth means of communication. Central English was once the whispered language of dying and dead men.

A more recent record of time spent in Pretoria Central is Steven Botha’s “Concrete Island” (in Frontline, October-November, 1987), a piece so frank and forthright that it makes Cold Stone Jug, once held to be such a shocker, seem tame indeed. To his confession Botha attaches a wordlist of contemporary prison slang, so that we may measure how, even there – half a century on – times and vocabulary have utterly changed. Only two words are recognisable from Bosman’s days: boer for warder and the perpetual old bandiet for the convict serving his term.

Stephen Gray

Johannesburg, 1999