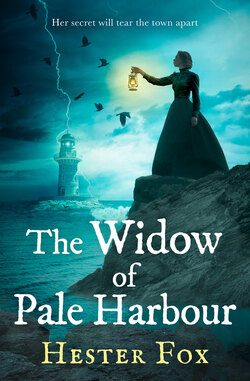

Читать книгу The Widow Of Pale Harbour - Hester Fox - Страница 16

5

Оглавление“I... Excuse me, but I was looking for a Mrs. Carver?”

The man was huge: tall, with broad shoulders, a gently squared jaw and a low, gravelly voice. She had only hesitated a moment before deciding to go to the door; if whoever had been leaving her the nasty surprises had decided to show up on her doorstep, they certainly wouldn’t have announced themselves. Beyond that, only one other kind of person would call on her, and that was someone who wasn’t from Pale Harbor. And that had to be the new minister that Helen said everyone was talking about. But with a dusting of light brown beard and shadowed eyes, he looked as if he had just lumbered off the docks, not come from a church. Suppressing her own surprise at the man who looked more like a sailor than a minister, Sophronia raised a brow.

“And you have found her,” she said with a gracious smile.

The man opened and closed his mouth a few times, and then looked behind him, as if checking to make sure that he had indeed come to the right house.

“I... My name is Gabriel Stone. The new minister.” He paused, and she let him stew in his confusion for another moment. “I’m sorry, but I thought that you...” He trailed off.

“Oh, don’t tell me,” she said with a sigh, “that you’ve been to dine with the Marshalls or the Wigginses already.”

Reddening, he started to explain himself, but she gave an airy wave. “No, no, you mustn’t apologize. They’re all well-meaning, but they haven’t the highest opinion of me. I suppose that goes for most of the town, as well. Please, come in.”

He was rather handsome in a rough sort of way, but when he passed her in the doorway, she couldn’t help her instinct to shrink back. He was so tall, so...big. Life with Nathaniel had taught her that men were dangerous creatures, and here she was, inviting a giant specimen inside her house. Closing the door behind him, she took a breath and drew herself up to her full height. Garrett was chopping wood in the yard, and Helen was nearby. She had nothing to fear. Besides, he was a man of the church.

“You’ll have to forgive Garrett and Helen their manners,” Sophronia said, giving him an apologetic smile. “We don’t do much entertaining nowadays.”

That was an understatement. They had never done much entertaining, even when Nathaniel was alive. But ever since learning that the town was to have a new minister, she had felt her heart lightening, a flicker of hope growing in her chest. People left Pale Harbor, but few came, and even fewer of those were anybody other than a poor fisherman down on his luck. Here was a man who hailed from Concord, the epicenter of all the exciting new schools of thought. If anyone could bring fresh ideas to Pale Harbor and persuade the townspeople to leave off in their superstitious ways, it would be him.

The minister followed her mutely, obediently. It was a strange sensation to feel the presence of a body behind her, in her space. Strange, yet not altogether unpleasant.

She led him to the parlor, her favorite room, with its circular walls studded with paintings and plush furniture upholstered in golds and greens. The parlor was also the Safest room in the house, thanks to the charms Helen insisted on hiding around the threshold, and the salt she was always sprinkling. It occupied the ground floor of the turret, so it was cozy and had only one door leading in and out to the hall. Cozy, beautiful, Safe.

“Please, have a seat.” She turned to clear some papers she had been reading off the sofa. When she turned around, the minister was lowering himself into the large armchair. Nathaniel’s old chair.

“Oh!” she exclaimed. “Not that one!”

He shot up like a bullet. “Oh... I didn’t... I’m so sorry.”

His cheeks flamed red and he looked genuinely distressed. What was wrong with her? He couldn’t possibly know the rules, and here she was proving the townspeople right in their belief that she was a madwoman. She took a deep breath.

“No, I’m sorry. It’s just...that was my husband’s chair.” She paused, twining her fingers together. “No one sits there anymore.”

“Oh.” He flicked his gaze to the chair behind him and then cleared his throat. “I didn’t realize.”

She forced a tight smile. “Of course not. Here,” she said, pulling up another chair and patting the back. “This one is more comfortable.”

Sophronia seated herself on the sofa, compulsively smoothing out her skirts. It had been so long since anyone besides Helen or Fanny had sat in the parlor, let alone an attractive man around her own age. Her pulse fluttered like a butterfly, but she was determined to be cool and composed. He might be a great thinker, but she had always been an excellent conversationalist, given the chance.

But the minister was silent, clasping his hands on his knees and looking exceedingly uncomfortable. Goodness, she knew the townspeople would have painted her in an unfavorable light, but what exactly had they told him to make the poor man look as if he were about to have a leg amputated?

She would just have to draw him out. “I heard you were making the rounds through Pale Harbor,” she said. “I wondered when I would find you at my door.”

He had been looking at her with unmasked curiosity, but at this he dipped his head and dropped his gaze under the fringe of his golden-brown hair. “I should have called sooner, but—”

With a wave of the hand she stopped him from having to make some paper-thin excuse. “No matter. I am very glad to meet you now.” And then, because she couldn’t help herself, she gave him a conspiratorial smile. “I’m not what you were expecting, am I?”

His gaze shot back up to meet hers, his lips parting as if in surprise at her frankness. He had full, sensual lips. They softened some of the roughness of his demeanor, and Sophronia had to force herself not to stare. She rushed on before he had a chance to respond.

“You’re not what I was expecting either. For whatever you have heard of me, I confess that when I heard we were to have a new minister, I envisioned a man of quite advanced years, with a gray beard down to his watch fob.” She stole a glance at his work-roughened hands, his broad shoulders. “It seems we were both mistaken in our preconceptions, for you must have imagined me quite the specter if the people of this town are to be believed.”

The minister looked down at his hands, as if it pained him to admit the truth. “Yes,” he murmured. “Something like that.”

Satisfied, she sat back a little in the sofa. “Well, I assure you I don’t have a tail.”

At this, the corner of his full lips quirked up ever so slightly, and an unexpected jolt of warmth ran through her. His face lost some of its hardness and his hazel eyes shone warmly, his smile all the more rewarding because of his reserve. To make a man like this laugh, well, that would be a coup indeed.

Some of the tension from her blunder about the chair lifted, and she saw him relax in his seat as well, crossing his long legs at the ankles. He draped his hands on the chair arms, and she caught a glimpse of the cut on his hand that was so bad that he had supposedly needed medical attention. She bit the inside of her lip to keep from smiling...it was tiny, hardly more than a scratch, and all at once she understood his game.

“Oh! Your cut. I nearly forgot,” she said, moving to the door. “I’ll ask Helen to bring some linen and hot water.”

“I really don’t need anything. It’s nothing.”

Sophronia blinked at him with big, innocent eyes. “Oh, but I thought you were injured?”

The tips of his ears pinkened. “It’s not so bad as all that,” he mumbled.

Just then Helen materialized in the door. “You called?”

“Yes,” Sophronia said, trying not to enjoy herself too much. “Our guest has quite the injury, and I was wondering if you would be a dear and fetch us some dressings for his wound?”

Helen’s sharp gaze darted to the minister and she scowled. But she dipped her head, murmuring, “As you wish.”

She stalked back out into the hallway, and Sophronia felt her cheeks flushing. Helen’s dislike of the minister was obvious, and terribly rude. “I apologize. She’s always been protective of me, but especially lately since—”

The minister’s gaze sharpened and Sophronia clamped her mouth shut. He didn’t need to know about the ravens, the feather, the sensation that she was being watched.

Sitting back down, Sophronia finally broached the subject that had been keeping her awake with excitement for the past week. “So, tell me about this new church.”

The minister opened his mouth and then closed it again. It might have been her imagination, but something like panic momentarily clouded his eyes and she thought he might leap out of his chair again. But then he cleared his throat and the look passed. “It’s... It will be transcendentalist. Similar to Unitarianism, if you are familiar with it?”

Transcendentalist! She had always admired the Unitarian school of thought, but the churches themselves were rather somber affairs. Transcendentalism, on the other hand, incorporated all the most progressive tenets of Unitarianism, such as the rejection of original sin and predestination, and then soared even higher with the idea that society and politics were corrupting forces to the purity of the individual. With transcendentalism, there was no need for society, and that suited her just fine.

She waited for him to elaborate, but nothing more came. She gave him an encouraging smile. “Well, I think it’s splendid. You must know Emerson, of course. I absolutely loved his first series of essays, and am anxious to get my hands on his second series. I devour everything I can from the leading minds on transcendentalism.”

“Emerson? Oh, yes.” He knotted his fingers together, not meeting her eye. “He’s very good.”

Sophronia frowned. He had not looked like she was expecting him to, and now it seemed that he would not converse easily on the subjects to which she had so looked forward. She tried again.

“I’d be curious to know what you think of his concept of the oversoul.” The essay explored the fascinating idea of the human soul and its relationship to other souls and how every person, alive and gone before, was connected. It was unlike anything Sophronia had ever read. “I found the theories intriguing and very much wanted to believe that Emerson’s beautiful prose held the truth, but it was difficult to do so when he gives us only anecdotes and stories. Perhaps, as a spiritual man, you need no such proof, but surely the purpose of an essay is to persuade?”

The minister looked like a fish out of water; he opened his mouth, but no sound came out. Just as Sophronia was about to repeat herself, Helen appeared with the tea, and whatever he had been about to say was forgotten.

“Thank you, Helen,” Sophronia said as she set the tray down. “You’re a treasure.”

“It’s nothing,” Helen said brusquely, but there was a faint glow of pride in her eyes. “Will there be anything else?”

“That will be all, thank you.”

The minister didn’t say anything as she poured out two cups of tea, just absently rolled some of the linen that Helen had brought around the cut on his palm. She hazarded a glance at him, and wondered what she looked like to him, with her scar, silver and smooth from time, tracing a path from her temple down to her jaw. Did he see a poised, well-spoken woman of means? Or was he able to see beneath her mask, to the scared, haunted ghost of a woman underneath?

When she looked up, she realized she had not been the only one studying the other. He had been staring at her hands as she prepared the tea. He cleared his throat, as if aware he had been caught, and took the china cup from her. He nodded to the paintings on the wall behind her. “You’re a collector,” he said.

She craned her head around and followed his gaze. Turning back, she gave him a shy smile. “Oh, yes. Are you an admirer of art?”

He nodded. Standing, he moved carefully to the wall. Sophronia knew her collection was exquisite, rivaling some of the best in places like the Athenaeum in Boston. But whereas the walls there were covered in somber portraits and classical allegories, her collection skewed toward the wild, with lots of rugged landscapes and people who were no more than tiny smudges against the grandeur of nature.

He must have been so lost in a world of turbulent waterfalls and sun-soaked valleys that he hadn’t turned when she stood to join him. Her sleeve brushed against his wrist as she pointed to a large watercolor in an elaborate gilt frame. “That’s a Turner,” she said, unable to keep the pride from her voice.

“It’s...beautiful,” he murmured.

It really was. A tempest of black waves swirled about an achingly fragile ship, shafts of light fighting to break through the cocoon of dark clouds. The painting was alive, full of movement, yet somehow peaceful; the ship was just one element of the storm, one little drama among the greater backdrop of nature. It was her favorite piece.

They moved along the wall as she pointed out some of her finer pieces, transfixed by the animation in his eyes as she discussed the merits of each.

He stopped in front of a small-framed article, illustrated with a lithograph, and nodded toward it. “Was your husband a writer?”

Pressing her lips together, she paused before answering. Why were men always so quick to attribute accomplishments to other men? “He owned a magazine,” she said. “That was Nathaniel’s one great kindness—he left me his magazine when he died. This was the front page from the first printing I oversaw as owner and submissions editor.”

He peered closer at the yellowed paper under glass and looked up at her in surprise. “What, you own Carver’s Monthly?”

“The one and only.”

He gave a long, low whistle and rocked back on his heels. “Damn.”

She raised a brow at the unexpected profanity, and he immediately colored. “Sorry. Only that I used to read it every week.”

“Then you have exceedingly good taste,” she said with a broad smile, finding herself unable to take offense. “It’s funny how for all their distrust of me, as soon as the townspeople think I can help them with something, they’re more than happy to put aside their prejudice and knock on my door. Just last month, Jasper Gibbs came to me with a volume of stories he had written, asking me to publish them in the magazine.”

“And did you?”

“Goodness, no. They were awful.”

Sun was coming through the windows in a low, hazy slant. They sat back down as the clock in the corner struck three. He’d been in her parlor for almost an hour, and though he was quiet, he was a good listener and she found herself wishing he would stay for hours more.

But before she knew it, he was rising to his feet and setting aside the tea, which he had hardly touched. “I’m afraid I’ve imposed on your hospitality long enough.”

“You did no such thing,” she said, trying not to let her disappointment show. “As you can imagine, visitors are few and far between, and I always welcome good conversation.”

Her hand paused on the doorknob before she released him out into the chill evening. “Do come again, Reverend. I believe we have much more to discuss.”