Читать книгу Tour of Monte Rosa - Hilary Sharp - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The Monte Rosa massif has inspired not only mountaineers but also poets, writers, visitors and explorers for generations. This mountain range is a visual bastion, dominating viewpoints from valleys on all sides. As Leonardo da Vinci wrote in his Milanese memoirs at the end of the 15th century, the Monte Rosa ‘is so high that it seems almost to overtake the clouds’.

The Tour of Monte Rosa is a journey of dreams, an adventure that goes way beyond a hike or trek, a voyage of discovery in one of the most fascinating Alpine regions. To treat it as a mere walking tour would be to miss out on so much: the varied culture of the Swiss and Italian valleys and mountain villages; the gastronomic specialities which change from one valley to the next; the people encountered; the rich history of the area; the wealth and diversity of plant life and animals.

This is a trek to be savoured. If you do not have time to complete it in a leisurely fashion you may be well advised to do a section one year and leave the rest for another visit, rather than miss out on the chance to immerse yourself fully in the experience.

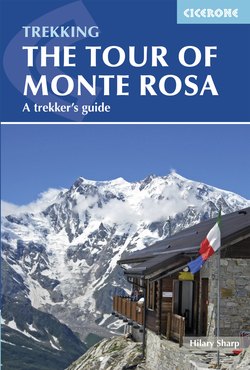

A great view of Monte Rosa from the Rifugio Oberto Maroli on Stage 6

Monte Rosa is far from being a single summit. This is the biggest massif in Western Europe, comprising ten defined summits which surpass the magical 4000m mark. Although now surrounded on all sides by resorts and mechanical uplift, the ascent of the Monte Rosa peaks remains a challenging undertaking, not to be underestimated. Winter and summer alike, the nearby slopes are home to skiers and tourists, but to reach a Monte Rosa summit you need to be fit and acclimatised. All around are glaciers, seracs and crevasses, and although in good sunny conditions deep snow tracks lead to the summits and give a sense of security, as soon as the fog comes down or the snow starts to fall this area becomes a very serious proposition indeed.

To walk around the Monte Rosa massif is to enjoy all the views and the incredible scenery with none of the dangers and perils associated with ascending the peaks. The Tour flirts just a little with the glaciers as it passes from Italy to Switzerland via the Theodulpass, leading the hiker into the high mountain world of ice and snow. But there are far more demanding ascents than this one on the Tour.

Apart from that short glaciated section this is a trek on non-glaciated ground. It is a wonderful route that climbs up from the valley bases through meadows, past summer farms and grazing cows, onto the higher rocky slopes where only the hardiest animals live, and over passes tucked up against the slopes of glaciated mountains, then descending new valleys, each different in character and scenery.

The region

The Monte Rosa massif forms part of the Pennine Alps (a mountain range in the western part of the Alps), and borders southern Switzerland and northern Italy. The Pennine Alps are located in France (Haute-Savoie), Switzerland (Valais) and Italy (Piedmont and Valle d’Aosta). The Petit Saint Bernard Pass and the Dora Baltea Valley separate them from the Graian Alps; the Simplon Pass separates them from the Lepontine Alps; the Rhône Valley separates them from the Bernese Alps; and the Col de Coux and the Arly Valley separate them from the French Prealps (Aravis and Chablais). The Pennine Alps contain the largest concentration of peaks over 4000m in Europe. The Swiss-Italian frontier forms the Alpine watershed and it is here that the most grandiose summits are to be found, their huge glaciers snaking down into the adjacent valleys: on the Swiss side flowing down to the Rhône, on the Italian draining to the Po.

The enormous barrier of the Pennine Alps represents the pressure zone created when the African tectonic plate collided with the Continental plate. Mountains were forced up and subsequent erosion has produced the spectacular scenery seen today. While very slightly less lofty than their famous neighbour Mont Blanc, peaks such as Liskamm, the ten summits of Monte Rosa, the Täschhorn, the Dom and the Weisshorn, to mention just a few, are at least equal in grandeur and splendour.

The Tour of Monte Rosa visits two countries, Italy and Switzerland. These are mountain regions, initially inhabited by people who probably arrived from other mountain valleys. To some extent cut off from life down on the plains, these regions have maintained their traditions and culture. Life was naturally harsh, especially during the long winter months. A common thread runs through the villages and valleys encountered on the trek – that of sustainable living – surviving on whatever you have locally.

The fabulously blue Gran Lago passed on Stage 2

The Italian regions are the Valle d’Aosta and Piedmont. A close look at a map will reveal that although it is only a day’s walk to get over from Switzerland to Macugnaga or Alagna, for example, it’s a very long drive from the main Italian valleys. This relative inaccessibility gives unique character to these remote Alpine villages. On the Italian side the trek passes through some villages incorporating a Walser settlement. These people have Germanic origins, their ancestors having made the journey to the mountains around AD1000. They settled in many Alpine regions, notably around Alagna and Macugnaga, and still preserve the basics of their original culture.

The Swiss part of the trek is exclusively in the Wallis canton, staying high above the Saas and Matter valleys. The relatively new Europaweg (established 2000) links with the long-existing Höhenweg to make the world’s longest balcony path (at least that’s how it feels) all the way from Saas Fee to Zermatt. While this trail is a visual joy, it does keep the hiker away from some of the charming villages in the valley – it may be that the future Tour of Monte Rosa takes to the valley paths (shown as Stage 8A in this guide) to avoid the Europaweg, which has serious maintenance problems, and the upside of this will be the chance to discover these traditional hamlets. Zermatt and Saas Fee – along with Grächen, which sits between these high-traversing trails – provide a good insight into life in this German-speaking part of Switzerland.

The Monte Rosa massif

When driving up from the lowlands of the Po Valley past Milan on a clear day you will notice a misty mass rearing up in the distance. Soon you will distinguish snowy slopes and rocky buttresses, but even so this huge massif seems completely improbable from the motorway. This is the Monte Rosa massif, and you will better understand its situation and associated culture and weather if you can visualise its exact location. The massif forms the southern extremity of the Pennine Alps, and is the first obstacle encountered when heading up from the southern plains. The massif is shared between Switzerland and Italy, situated in the Italian regions of Piedmont (provinces of Verbania and of Vercelli) and the Valle d’Aosta (province of Aosta), and the Swiss canton of Valais (Wallis). The name pied monte literally means ‘at the foot of the mountains’.

Monte Rosa’s four highest summits (L to R): Nordend, Dufourspitze, Zumsteinspitze and Signalkuppe with the Margherita Hut just visible close to its 4559m summit

Facts and figures

The Monte Rosa massif is very large – the biggest in the Alps – with 22 peaks over 4000m. Ten of these peaks form Monte Rosa itself. The high point of Monte Rosa is the Dufourspitze, which at 4634m is the second-highest peak in the Western Alps. The official limits of the Monte Rosa massif are:

West Theodulpass (3317m)

East Monte Moro Pass (2853m)

North Schwarzberg-Weisstor, next to the Rimpfischhorn, in the Mischabelgruppe (4199m)

South Col d’Olen (2881m).

Matters are made more complicated by the fact that the massif straddles the Swiss-Italian frontier and thus many of the summits have both Italian and Swiss names (and sometimes different altitudes as the maps do not always concur!).

The northern side belongs to Switzerland and holds the greatest glaciers, such the Gorner Glacier (Gornergletscher), which is the second-largest glacier in the Alps and runs down to the Zermatt Valley (Mattertal). The Italian side is far less glaciated since it faces south and east, and here the most important is the Lys Glacier (Ghiacciaio del Lys or Ghiacciaio di Gressoney).

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Monte Rosa is its East Face, which is the highest in the Alps. There is a height difference of around 2470m between the meadows at the end of Valle Anzasca to the top of the mountain. Seen from Macugnaga, the face forms a steep and colossal barrier – virtually a Himalayan wall in the Alps. It features one of the longest couloirs of the Alps, known as the Canalone Marinelli after its first ascentionists. Also in the Monte Rosa massif, between the Nordend and the Dufourspitze, is the highest pass in the Alps – the Silbersattel (4517m).

Why ‘Rosa’?

The origin of the name ‘Rosa’ is lost in the mists of time. One version has it that the name comes from the beautiful pink colour (rosa) that tints wide glaciers and snowfields at sunset and sunrise, when the first and last light of day hits the different faces of the massif. When seen from the low valleys and big cities such as Turin and Milan Monte Rosa appears huge and magical, almost floating on a thin layer of clouds. When the sun goes down, the last rays of light bathe the mountains with a strange palette of colour. However, this interpretation could just be romantic nonsense. It seems more likely that the name ‘rosa’ comes from an ancient dialect word rouèse or roises, meaning ‘glacier’.

First ascents

The achievements of the earliest explorers of the Monte Rosa summits are undocumented how can we know … how can we know how many crystal hunters or shepherds tried to climb these peaks? But the first recorded ascent of the Monte Rosa massif is said to have taken place in 1778, when seven Italians from Gressoney went up from the south side, lured by tales of a mythical lost valley. The high point reached by this group (at about 4000m) was called the ‘stone of discovery’.

Ibex at Bettaforca with the Parrotspitze summit behind seen from Stage 3

Recent history of mountaineering on the massif is firmly linked to Italian priests: the first ascent belongs to Alagna’s priest, Pietro Giordani. He reached 4046m (now called Punta Giordani) in 1801. To Giuseppe Zumstein belongs the ascent of the Zumsteinspitze (4563m) in 1819, and to N Vincent goes the ascent of the Piramide Vincent (4215m) in 1819.

In 1842 another priest, Gnifetti (a name associated with many Monte Rosa peaks), reached the Punta Gnifetti (Signalkuppe) (4554m). In 1861 an English expedition (EN and TF Buxton and JJ Cowell) climbed Nordend (4612m) with two Guides. In July 1855 an English expedition (J Birkbeck, C Hudson, E Stephenson, and J and C Smyth), with Swiss Guides, attained the highest summit of the range, the Dufourspitze (4634m).

The first difficult route, the Nordend East, was climbed by an Italian expedition (led by Guide L Brioschi) in 1876, and the first winter ascent belongs to another Italian expedition (L Bettineschi, F Jacchini, M Pala and L Pironi) in February 1965.

Glaciers

Glaciers and glaciated mountains feature strongly all along the Tour of Monte Rosa. The valleys have been carved by the ice, and many people now come to the Alps to see what remains of these huge frozen rivers. The terrain encountered on the trek has been largely shaped by glaciers – mainly long gone – and all around are high snowy mountains. The trek has one short passage on a glacier which, although quite flat and apparently banal, should not be underestimated.

Glaciers respond to climatic changes. In cold periods with heavy snowfall glaciers expand downwards, only to retreat in warm dry periods. Over the course of the centuries the climate has changed more than once, and these fluctuations have influenced the life of the Alpine populations.

The Middle Ages were a time of relative warmth which favoured the colonisation of the Alps at increasingly high altitudes. Glaciers retreated considerably and artefacts found at now-glaciated passes are evidence that much of this terrain was ice-free for many centuries. The 16th century saw the beginning of the Little Ice Age, a cold period of heavy snowfalls which lasted three centuries, and the glaciers regained much territory. The advancing glaciers buried many of the high pastures and gave rise to fear and superstition among mountain people – the ice was literally pushing up against their front doors, and they were moved to call the priests to exorcise these demonic forces.

The mid-19th century saw the start of the warm period which has continued, with occasional colder intervals, to this day. The extent to which we are now in a natural cycle or whether the recent fast melting of the glaciers is due to the effects of modern civilisation may be debated, but there is no doubt that the current warming is very rapid.

Ancient passes

Many of the trails used by the Tour of Monte Rosa have been used for centuries for all sorts of different purposes. In the Middle Ages the Alpine climate was warmer by several degrees than it is today, and before motorised transport it was often easier and safer to go over the high mountain passes than to descend to the main valleys such as the Rhône and the Aosta. Frequently the mountain valleys were rendered impassable by deep gorges, or were prone to rockfall or landslides. While the high passes carried their own risks – bad weather, cold, exhaustion, attack from marauders – they were usually more direct and less tortuous.

There were abundant reasons for wanting to travel from one valley to the next.

Trade: in times past people bartered goods rather than dealing in money. Goods that were needed in the Alps included salt and spices, so the mountain people would take their own goods to trade. The wines from the Aosta Valley were sent over to the Valais and Tarentaise by the so-called Route des Vins (which went from Chambave to the Rhône Valley, probably across the Theodul and Collon passes).

The farmers would take their cattle over into neighbouring valleys to graze as part of the transhumance method of farming.

People travelled surprisingly long distances for work; for example much of the Alpine architecture in Switzerland is based on the work of Italian builders from the Valsesia region, near Alagna.

Sometimes people needed to migrate because they had too many enemies in their native valley, or conditions had made survival there untenable.

The Monte Moro Pass (L to R): the lift station, the Oberto Maroli hut and the golden Madonna (Stage 6)

History tantalises us with fascinating stories about these travels – fortunes lost, treasures found, lives risked. Now as we trek through the mountains, generally comfortable in our high-tech gear and with well-filled stomachs, it’s interesting to try to imagine the trepidation that travellers hundreds of years ago would have felt before setting out on these highly risky ventures. The vagaries of Alpine weather meant that any excursion into the hills brought with it a risk of bad weather, not to mention illness or even attack. The frequent presence of chapels and crosses en route attests to the need to put their life in God’s hands. Hence on several cols in the Alps – such as the Grand St Bernard, Petit St Bernard and Simplon – we find hospices, erected by religious people to provide safe haven for those poor souls in need of food, shelter or security while trying to get to the next valley.

Theodulpass (3301m)

This pass is one of the most famous in the western Alps and a major crossing point on the Tour of Monte Rosa trek. In Roman times it was called Silvius, and is documented as early as AD3. The name Theodulpass dates from the late 17th century. It was named after St Theodul, a Christian missionary and the first Bishop of Valais towards the end of the fourth century. He made numerous visits to Italy, probably via this pass which now bears his name.

In 1895 54 coins dating from 2BC to AD4 were found just below the col, and these are now in an archaeological museum in Zermatt. It must certainly have been hotter and drier in those days, since these and other artefacts attest to the passage of the col on foot and on horseback. It would seem there was a small settlement on the col providing provisions and guided passage. From the 5th century onwards winters became more rigorous and the glaciers began to grow. Commercial caravans abandoned the route, but from the 9th century the glaciers regressed and there was a return of activity across the pass, with several monastic orders settling on both sides of the massif. In 1792 Horace Benedict de Saussure (famed as the main instigator of the first ascent of Mont Blanc) came this way and spent some time at the col measuring the exact altitude of the Matterhorn. Whilst there he apparently found the remains of an old fort built in 1688 by the Comte de Savoie.

The Little Ice Age from the 16th century onwards led to colder conditions and the glaciers grew accordingly. Cols such as the Theodulpass became more and more difficult to cross and would-be travellers were regularly victims of accidents while attempting this passage, be it from the cold, avalanches or crevasses. In 1825 a merchant fell into a crevasse with his horse, allegedly taking 10,000 francs with him – an incentive for bounty hunters for years to come. In the 20th century conditions on this pass became much easier – in 1910 a herd of 34 cows successfully made the passage – but, nevertheless, care must be taken here.

The Walser community

The Italian part of the Tour of Monte Rosa passes through several areas of Walser settlement. The Walsers are descended from Germanic peoples who, a thousand years ago, left their homeland to migrate throughout the Alps. They came from the German-speaking Upper Valais region – in German ‘Wallis’, hence Walliser people, giving the name ‘Walser’. Why they left their homeland is not known – possibly a natural catastrophe, climatic change, plague or a desire to roam – but wherever they settled they preserved their ancient German language, customs and traditions.

Monte Rosa towers over the hamlet of Alpe Bors (Stage 4)

They settled in the higher reaches of the Alps, not just in Italy but also in the Swiss Bernese Oberland and the Chablais region of France. They particularly favoured the southern Alpine valleys, especially those surrounding Monte Rosa. The Walser colonisation was achieved peacefully, as the Italian feudal lords in the Valsesia Valley had little to lose in granting them high-altitude land (generally above 1500m or even higher) which was regarded as inhospitable and therefore not exploited by the locals.

In return for maintaining these Alpine lands the Walsers were allowed freedom. Their communities were not subject to the laws of the region, and in effect they had their own sovereignty. The newcomers did not immediately establish relations with the locals, and initially received supplies of staple commodities such as salt, metal tools, cereals and clothing from the Valais. Later the colonies became practically self-sufficient and the umbilical cord linking them with their old country was broken. Their integration became complete when their self-governing parishes were recognised.

The inhabitants of these isolated colonies had to work hard to survive: they had to clear forest, till the land, create fields and meadows for cultivation and grazing, build houses and, during the summer, produce everything necessary to feed their families and animals during the long winter months. Their ethnic and linguistic isolation and difficulties in communication and transport made them fiercely independent and proudly free. They say that to breathe the air of the Walsers is to breathe the air of freedom.

(L to R) Signalkuppe, Zumsteinspitze and Dufourspitze seen from Nordend

The Walser culture is expressed not only through language and traditions but can also be seen in their traditional architecture and settlement patterns. The Walsers had to survive in rough conditions, so they became experts in farmwork, making tools and cultivating crops at altitude. Their houses were often built of wood and these buildings can be seen today (such as at the hamlet of Otro, above Alagna) and will be strung with tools, their large balconies supporting wooden frames for drying hay. Essential to the Walsers’ diet was rye bread, baked twice a year (in spring and autumn) in the communal oven. During the winter months it was kept on a special wooden rack hung out from the walls, to prevent attack by mice.

Those houses high in the meadows were isolated from each other to provide larger areas for cultivation around each one. In the towns, such as Alagna and Macugnaga, the houses were clustered together in small groups called frazioni (hamlets). Each hamlet, surrounded by a large area of fields, consisted of up to 12 private houses and some communal structures such as the chapel, one or more watermills, a big oven and a stone fountain, which always represented the focal point of the community. This decentralisation of the hamlets was carried out for reasons of safety (to avoid mass destruction through avalanches, landslides and flooding) as well as to gain the maximum amount of sunshine and to make use of local water supplies. In every hamlet the houses were built close together so that the roofs were almost touching, thus protecting the narrow lanes below from rain and snow.

This concentration of dwellings enabled quick and easy access to the communal services and to the cultivated fields. Walser houses could provide shelter for two or more families, together with their cattle. Stable, dwelling and barn – all the basic needs for the survival of mountain farming people – were concentrated under a single roof. Time for the Walsers was regulated by the seasons, as it still is for many country people, and their society was organised by common rules: everybody had to help build the houses, members of each family had to co-operate in snow shovelling and street maintenance, and so on.

Today the Walser community maintains its unique culture, architecture and language, albeit on a limited scale. Take the time to study the villages and hamlets encountered along the Tour to better understand the harsh way of life endured in these mountain communities. There is a Walser Museum in Alagna (www.alagna.it/en/ and click on ‘Alagna’ and then ‘The Walser Today’) and also one at Macugnaga in the hamlet of Borca.

The Otro Valley (Stage 4)

The valleys

Monte Rosa and its neighbouring summits form a huge massif from which glaciers descend on both the Swiss and Italian sides, flowing into valleys. On the Swiss side two main valleys, the Mattertal and the Saastal, drain down to the Rhône Valley, while on the Italian side it is a little more complicated. The Valtournanche, the Ayas Valley and the Lys Valley all descend to meet the Aosta Valley, where the main river is the Dora Baltea. The Valsesia drains down to the Po while the River Anza, which flows down the Anzasca Valley from Macugnaga, flows into Lake Maggiore.

Mattertal

Mattertal means ‘valley of meadows’. Legend has it that long ago, before the Alps were discovered by climbers and walkers – when mountains were still regarded as the abode of evil spirits and dragons – people believed that a magic valley existed, hidden among the glaciers of Monte Rosa, among the big peaks. It is said that in 1788 a band of men set out from the Valle di Lys in Italy in search of this Eldorado. They climbed over the pass between Monte Rosa and Liskamm (now the Lysjoch) and looked down to the valley below. However, they were disappointed only to find more glaciers, rocks, snowfields and deep ravines. Where were the grassy meadows, the land of milk and honey, which they had been looking for? Perhaps they would not be so disappointed now, seeing how the dawn of mountaineering and the consequent explosion in tourism have made this valley a haven for holidaymakers and a most lucrative place for the inhabitants.

Saastal

The Saas Valley is surrounded by well-known 4000m peaks such as the Dom, Täschhorn, the Allalinhorn, the Strahlhorn, the Rimpfischhorn, the Weissmies, the Lagginhorn…Settlements in the valley go back to the days of the Celts. The inhabitants of the Saas Valley used to form a self-contained community, but in 1392 the area was divided into four politically independent communities. Each settlement retained the basic name ‘Saas’, the origin of the names Saas Almagell, Saas Balen, Saas Grund and Saas Fee.

For centuries merchants and traders roamed through the Saas Valley across the Monte Moro and Antrona mountain passes to Italy. These trade routes were also used by pilgrims. Even the Romans used to cross these cols, attested by the discovery of ancient coins at the Antrona Pass in 1963. Although the villages in the Saastal grew during the early 20th century, Saas Fee was not developed for tourism until much later, perhaps because access to this higher village was more difficult. The first Saas Fee hotel was constructed in 1880. In 1951 the road up from Saas Grund to Saas Fee was finally completed.

Valtournanche

Dominated by the Matterhorn (or rather Monte Cervino, to give it its Italian name), this Italian valley really represents the Valle d’Aosta. Its first language traditionally was French, hence ‘Breuil’ in the name of the village at the head of the Mattertal. The valley has its base down at Chatillon, south of Aosta. The Marmore river runs along the valley, draining the glaciers of the Dent Hérens, Matterhorn and Plateau Rosa peaks, among others.

Ayas Valley

This valley is formed by the Evançon river. Its highest village is St Jacques and it meets the main Aosta Valley at Verrés.

Lys Valley

Often known as the Gressoney Valley this is a long and winding gorge that descends from the slopes of Liskamm following the route of the Lys river all the way to Pont St Martin. It is a valley rich in history with several interesting churches and villages.

Valsesia

With its base away down near Novara, far closer to Milan than Aosta, the Valsesia Valley winds its way up to Varallo where the road splits, then continues up to another junction at Balmuccia. The glacier-fed River Sesia gushes down here, and the valley above this point is known as Upper Valsesia. Alagna Valsesia is the highest village in the valley and is surrounded by mountains. This is the home of the Walsers, emigrés from the north via the Valais (Wallis) region (in what is now Switzerland) from the 10th century. Today you’ll still hear people speaking the old dialect, based on long-extinct Old German.

Anzasca Valley

This is the most eastern valley coming down from the Monte Rosa massif. It is very close to the Swiss frontier and it descends from Macugnaga to meet the Toce river near Domodossala, the main access point for Macugnaga, on the main road and railway from Visp/Brig to Milan. The Toce river flows down into Lake Maggiore, a famous tourist spot.

Macugnaga seen from the summit of Nordend

The main towns

Saas Fee

Saas Fee lies in an idyllic valley surrounded by the highest mountains in the Swiss Alps. No less than 13 peaks of 4000m or more encircle the village, which has christened itself ‘the Pearl of the Alps’.

Saas Fee can be reached by car or bus. No cars are allowed to enter the town (they have to be left in a car park at the entrance to the town); only small electric vehicles operate on the streets (and some petrol-driven refuse trucks). The resort buzzes in both summer and winter, and features the highest underground funicular railway in the world (the Metro-Alpin), which in winter serves the skiing area. It also takes the visitor to the highest revolving restaurant in the world, at 3500m. The campus of the European Graduate School, a university of the Valais canton, is located in Saas Fee.

Traditional costumes in Saas Fee

In old documents Saas is also called Sayxa, Sausa, Solxa and Solze, from the Latin salix meaning pasture. The origins of the word ‘Fee’ have not been established, but it could come from vee (cattle), ves (mountain), fö or föberg (sheep mountain) or fei (fairy).

Although the region was described by S Grunert in his 18th-century travel book as the ‘most abominable wild region of Switzerland’, people started to visit the Saas Valley towards the late 18th century and early 19th century precisely because they were attracted by that sort of landscape. They included authors of travel books, cartographers, mineralogists, botanists and landscape painters. Saas Fee was somewhat cut off from the valley until the main road from Saas Grund was constructed in 1951, resulting in an increase in tourism. Despite the influences of modern life, many traditional customs exist to this day, including home-made costumes (which are worn at various events) and traditional music. There are several costume and music societies which can be seen at festivals and parades.

Zermatt

Zermatt is a town of contrasts. Dominated by the Matterhorn, it is nowadays assured a place high on the list for many people travelling in the Alps. With the advent of European travel in the 18th century the inhabitants of Zermatt quickly became aware that they were sitting on a potential goldmine, and since then the town has developed in line with the huge commercial success of the Matterhorn’s image. However, it still maintains its mountaineering roots and is a Mecca for alpinists.

One way to travel in Zermatt

Zermatt means ‘to the meadows’ (zer being ‘to’ and matt meaning ‘meadow’). However, 500 years ago Zermatt was still called Prato Borno, named by the Romans many years before and meaning ‘cultivated field’. Zermatt has been a settlement since ancient times – apparently there was a scattering of tiny dwellings there as early as AD100 – but until about AD1100 there was no real central settlement. For centuries it was a place of trade and exchange between neighbouring valleys. Zmutt, situated just above Zermatt – today just a small hamlet with a good view and nice restaurants – was in those days the last place en route to the Theodulpass between Italy and Switzerland, and thus an important spot with its customs post, inns and guiding service for the passage to the col.

As the climate began to change (in the 12th century), the Theodulpass gradually became impassable for parts of the year, and the village that had existed there was abandoned. The 16th–18th centuries were particularly cold – the Little Ice Age – and the glaciers advanced right down to the valleys. The passage of the cols became impracticable, even in summer. Life was almost impossible in the high villages, and many people moved away.

On top of the Breithorn, on top of the world!

In the early 1800s climatic conditions began to improve, and for the first time foreign tourists visited the Zermatt Valley. As first they were greeted with hostility and mistrust, but gradually the villagers started to set up inns to accommodate these travellers. Until the carriage road was built from St Niklaus in 1858–60, Zermatt could only be reached on foot or by mule along a rough path. Yet many illustrious visitors, ranging from mountaineers to artists to explorers, were attracted to the unique experience of the town. The arrival of the railway for summer use in 1891 proved a real boost to tourism. The introduction of skiing to the Alps in the early 1900s assured the area’s future, but also the relentless exploitation of Zermatt, as it did all other Alpine resorts – the term ‘White Gold’, used to describe the snow, has proved to be very apt.

It was only in the 1960s that the route as far as Täsch was made into a proper road. Zermatt town council agreed that cars would not be allowed into town, and in 1972 the inhabitants rejected a proposal for a public road to Zermatt. So the town remains car-free, although the silent electric vehicles used throughout town are arguably far more dangerous as they sneak up behind unsuspecting pedestrians. In 1979 the Klein Matterhorn cable car, at 3820m the highest in Europe, was completed.

Breuil-Cervinia

Breuil was the original name of this village, nestled at the top of the valley under the slopes of Monte Cervino and frequented since Roman times. ‘Cervinia’ was the name given by the fascists under Mussolini during World War II, when they wanted to destroy the long-standing Francophile culture of the Aosta region. The Valdôtain people (of the Aosta Valley) refused this attempted reversal of their culture and took up arms, retreating to the hills and waging a war of resistance. After the liberation most places resumed their French names, but at Breuil-Cervinia they kept both names – presumably the incorporation of the Italian name for the Matterhorn, Cervino, was regarded as a good tourist attraction.

Breuil-Cervinia is a fairly typical resort town with a mix of old and new. The church sports a rather fine sundial and there are some attractive houses, but in general the architecture is not exceptional.

Gressoney St Jean and Gressoney la Trinité

Gressoney St Jean is a located on a wide, lush plain. The surrounding landscape is very interesting because of the excellent view of the majestic mountain ranges and of the Liskamm Glacier, from which the Lys river emerges and runs down the valley.

In the centre of the village some well-preserved Walser houses surround the parish church, dedicated to St John the Baptist. This church was rebuilt in 1725 on the ruins of a previous edifice dating from 1515. Its roof has a big overhang, and the 16th-century bell tower is characterised by a spire and mullion windows. In the parish museum visitors can admire a big crucifix dating back to the middle of the 13th century, probably one of the oldest masterpieces in the Aosta Valley. Not far from the village centre is a charming small lake, whose emerald green water reflects numerous mountain peaks. In 1894 Queen Margherita ordered a castle (Castel Savoia) to be built in this panoramic spot, known nowadays as ‘Belvedere’, and often holidayed here. One of the best examples of Walser culture is undoubtedly the women’s traditional red and black costume with a white blouse trimmed with lace and a precious bonnet made of golden filigree. These can be seen during local festivals, one of which is St John’s Feast that begins on the evening of 23 June, when fires are lit in different villages, and lasts for three days. On this occasion the inhabitants of Gressoney go to Mass wearing their traditional costumes.

Gressoney la Trinité has limited facilities – pharmacy, hotels, a shop. Gressoney St Jean has far more, including some quite unexpected shops for such a small town, and there is a regular bus service between the two villages. Between Gressoney la Trinité and Gressoney St Jean there is a marble quarry.

Alagna

Officially named Alagna Valsesia, this charming village (an ancient Walser settlement) is situated in the upper Valsesia at 1205m and is one of the most important ski resorts in Piedmont. Nestling at the foot of Monte Rosa, it is also the starting point for a number of beautiful mountain walks. The village is full of reminders of its Walser origins. In the hamlet of Pedemonte, just a short way from the centre of Alagna, is the Walser Museum, a wonderful record of Walser life. There are also the remains of a 16th-century castle.

The chapel at Otro (Stage 4) sports a typical fresco

The parish church of St John the Baptist in the centre of Alagna is also well worth a visit. The present church was built on the site of an older chapel dating from 1511, and the main altar is an authentic masterpiece of 17th-century baroque work. The village is known for its wood art, and there is evidence of the skilled work of traditional wood artists who were active up and down the Valsesia Valley. There is also a history of mining at Alagna. The main evidence for this is the feldspar mine seen on the road up to Rifugio Pastore, but at one time gold was also mined here.

On the far side of the centre of Alagna lie the hamlets of Dosso, Piane, Rusa and Goreto, typical Walser settlements where little churches provide the centrepoint for a cluster of baite, the Walser chalets.

The whole of this area falls under the protection of the Upper Valsesia National Park.

Macugnaga

The small town of Macugnaga feels far from anywhere. If you have to bail out from here it’s actually easier to get back to Switzerland than to the Italian valleys further along the trek.

Macugnaga has a colourful past, being not only a high Alpine settlement but also having a history of goldmining. That is long gone now and the town survives mainly on its winter season when people come to ski under the slopes of Monte Rosa. Again the Walser community has made its mark, and there are several fine examples of Walser architecture.

The town is centred round its main square where most of the hotels and bars are situated. As soon as you leave the square you enter quiet old side streets, the silence only broken by the roar of the Anza torrent, swelled by glacial melt during the summer months.

Wildlife and vegetation

Plants and flowers

The plants and flowers encountered on any trek vary throughout the year, and even though an Alpine trek of this nature can only be done as a regular walk during the summer months there is a huge change in vegetation between late June and late September. Early on in the summer season the lower slopes around the villages will be a blaze of colour as all the meadow flowers are in bloom up to around 2000m – trumpet gentians, pasque flowers, alpenrose, vetch, martagon lilies…a perfect time to be walking at lower altitudes.

Higher up there may still be nevé remaining from winter, and most slopes will only just be snow-free, so the flowers will not yet be in bloom. As the summer progresses many of the lower meadows will be scythed for haymaking, but above 2000m the flowers will start to bloom. Again the alpenrose – a member of the azalea family – is prevalent, covering the slopes from about 1500 to 2500m. Its pink flowers make a wonderful backdrop for hiking, and trekking in the Alps when these flowers are in season is an absolute joy. Many Alpine flowers that grow at lower altitudes will also be found here, but in a smaller and more intensely coloured form. The houseleeks that grow on the rocks, astrantia and orange hawksbeard are all Alpine versions of regular garden flowers. Above 2500–3000m are the real Alpine gems, tiny jewel-like flowers, so small that they get lost in the rocky crevices. These have a very short growing season of about six weeks before the return of the snows. Hence their miniature, energy-efficient size, and bright colours to maximise their attractiveness to pollinating insects. Look out for starry blue gentians and clumps of pink rock jasmine on the high rocky passes, as well as the rare King of the Alps which you may be lucky enough to spot on a couple of the cols. Scree slopes are often home to the amazing purple and orange toadflax, while on the highest ground you’ll find the pinky white buttercup-like flowers of the glacier crowsfoot, allegedly the flower that grows at the highest altitude in the Alps.

The flower everyone expects to see is the edelweiss and you should spot some somewhere along this trek, providing it is not too early in the season – it doesn’t generally bloom before mid-July. Although the edelweiss has become known as the classic Alpine flower, many people are disappointed at first sight – its white furry bracts can appear rather grey. Look closely, however, and you’ll see that the real flower is the yellow centre, and seen in sunlight it is rather fine.

Hardy alpine flowers have to endure extremes of temperatures and very barren ground

In September the meadows will no longer be full of flowers, but a keen eye will still spot many different species at higher altitudes. Lower down there will be a few late-season blooms such as purple monkshood growing next to streams, or the Alpine pansy, which seems to keep going for the whole summer. In late summer the lower paths will be bordered by bilberry bushes, laden with berries, and also raspberries, the lure of which makes for slow progress at times. There are also some low-growing bushes bearing shiny red bear berries, used to make a savoury jelly.

There is a wide variety of trees to be found, depending on altitude. The Alps are known for their coniferous forests, largely composed of spruce and pine. These forests are brightened up by larch trees, the only deciduous conifers, which lose their needles each winter. They are a pleasant light green colour in spring, and their needles turn golden before falling in the autumn. Larch is one of the best woods for construction, and most old chalets are made at least in part from this beautiful red wood.

A tree peculiar to the Alps is the Arolla pine (Pin cembro) which has long needles and is often seen on the upper limit of the treeline – the higher up it grows, the smaller and more stunted it is. This extremely hardy tree can resist temperatures as low as −50°C and is indifferent to soil quality or slope aspect. Its wood is one of the most sought after, especially by sculptors. Its cones are sturdy, and the seeds too heavy to be blown by the wind. They are eaten by birds, notably the nuthatch, which stores seeds in cracks in rocks. Hence the Arolla pine is classically found growing out from the most improbable boulders.

Wildlife

One of the highlights of walking in the mountains is the excitement of spotting wildlife. In the Alps you may see a whole host of animals and birds along the trail. The chamois, ibex and marmot are the three ‘must-sees’, but plenty of other animals also inhabit these mountain valleys, meadows and boulderfields. In the forests are several types of deer, generally seen early in the morning or at dusk. Wild boar live below about 1500m and their snuffling antics often churn up the edges of the footpaths. The chewed pine cones lying on the trail betray the presence of squirrels, which will probably be spotted nipping from tree to tree.

If you are first on the trail you have the best chance of a wildlife sighting, but don’t make too much noise or you will scare everything away. The meadows and rocks are home to the mountain hare, which is very timid and more often seen in winter – or at least its tracks are – and the stoat which scampers around rocks, curious but very fast. They say there are lynx in the Alps but they are either very rare or very cautious: seeing one would be quite a surprise. Wolves are being reintroduced into the Wallis region, but you would be unlikely to catch a glimpse of one.

Ibex are often seen on the more remote parts of the Tour

Above there is a wealth of birds, ranging from the very small to the very big. Any forest walk will be accompanied by the happy chirping of tits, finches and goldcrests, and the drilling of busy woodpeckers. Buzzards are common at the lower levels and, higher up, golden eagles are not rare, especially on bad-weather days when they circle far above on the air currents. On the high cols you will be joined by Alpine choughs the moment you get out your picnic. These black birds, recognisable by their yellow beaks, are known to live at altitudes as high as 8000m in the Himalayas. But the king of all the birds has to be the lammergeier or bearded vulture, reintroduced throughout the Alps over the last few years. You would be lucky to spot one, but if you see a huge bird with an orange underbelly that only seems to flap once an hour it is probably a lammergeier. These giants, long regarded as meat-eating predators, live almost entirely off the bones of dead animals, dropping the bones from on high to break them up for easier consumption. Just rarely you may see a heap of broken bones lying near the trail.

Stoats often play among the rocks

It is a great privilege to see any of these creatures, and while taking photographs is a superb way to immortalise the moment, it is crucial to leave the animal undisturbed. Besides, there’s nothing so ridiculous as watching a would-be photographer stalking his subject while the animal moves further and further away! Fit your camera with a strong zoom lens, or be satisfied to keep the memory in your head.

When to go

The Tour of Monte Rosa crosses cols often close to 3000m, which are likely to remain snowy well into June. The huts used on the trek generally do not open until late June or early July, so it is not advisable to set out before the summer Alpine season begins. However, later is not necessarily better as fresh snow is quite likely late in the season.

Névé on certain sections of trail can make passage quite difficult – either because the snow is hard and slippery or because it’s a hot, late afternoon and the snow has melted and doesn’t hold your weight. For example, the stage from Testa Grigia to Plan Maison/Cime Bianche is really only feasible when there is no snow on the slopes, be it névé or fresh snow. Similarly the climb to Monte Moro from Mattmark can be very tricky in névé or fresh snow as there is a passage across sloping rocky slabs which is aided by cables.

In addition to thinking about snow conditions, you have to decide if you are going to walk every part of the route or whether you intend to take the occasional lift. If you’re planning to take lifts, be sure of their open season – usually early to mid-July to early September. In line with the lift season, the hotels in villages such as Macugnaga have a short summer season.

The wild and scenic Ruesso Valley leading up to the Gabiet Lake (Stage 3A)

The best time to do this trek is during this brief summer holiday season – late July to late August. The earlier you go, the more flowers there will be on the hillsides; the middle of the season sees the most holidaymakers in the Alps; the end is generally noted for beautiful autumn light, but can be prone to fresh snowfall above 3000m.

If in doubt call local tourist offices or the huts for up-to-date information on conditions.

Getting there

Zermatt/Saas Fee

By air

The nearest airports are Zurich and Geneva. From Britain these airports are served by many airlines, including British Airways (www.britishairways.com), Easyjet (www.easyjet.com), Swiss International (www.swiss.com). Aer Lingus (www.aerlingus.com) fly to Geneva from Ireland.

Onward travel to Zermatt or Saas Fee is best done by train.

By train

Eurostar run a regular service from London to Geneva, which takes about 6 hours (www.eurostar.com) and for travelling around once in Switzerland the train service does not disappoint. The Swiss railway network is incredibly efficient; timetables and online ticket sales can be found at www.sbb.ch. For the best prices it may be worth buying a Swiss rail pass – all the different passes are described in detail on www.myswissalps.com/swissrailpasses with helplines and forums to advise on the best choice of pass.

By car

If you drive to Switzerland you’ll need to buy a motorway vignette on entry to the country, which in 2014 cost 40CHF for the year – this price has been held for years and each year there is talk of a considerable hike in price, so don’t be surprised if it costs more than this in the future. You cannot take the car to Zermatt, but must park at Täsch and take the train up to the town. Saas Fee is also a car-free resort with a large paying car park at the entrance to the town. The other Saas villages, notably Saas Grund, all allow cars and have lots of parking areas.

By bus

Eurolines offer a regular service from Britain and Ireland to Switzerland, serving both Geneva and Zurich. Although the journey is long the price is competitive: www.eurolines.com tel: 08717 818178.

Breuil-Cervinia/Gressonney/Alagna

By air

The nearest airport is Turin (www.aeroportoditorino.it). The other option is Milan Malpensa (www.milanomalpensa-airport.com). Turin and Milan Malpensa airports are served by various airlines, including British Airways (www.britishairways.com) and Easyjet (www.easyjet.com).

By train

There is a train service from Milan to Turin and a train and bus service from Turin to Aosta, then good bus services up the valley to Breuil-Cervinia. There is no direct connection from Turin or Milan to Cervinia; you have to change buses at Châtillon. The bus stations are in the city and not at the airports.

By car

Driving in Italy is generally good fun so long as you have an adventurous spirit. The motorways usually charge tolls.

By bus

Eurolines offer a regular service from Britain and Ireland to Italy with stops at Turin and Aosta and Châtillon (at the bottom of the valley up to Cervinia): www.eurolines.com tel: 08717 818178.

Access to other towns

From Zurich, Geneva or Turin airports you can reach any of the other towns encountered during the trek. In Switzerland the train is the best way to get along the main valleys, from where the yellow Swiss PTT buses give access to all but the remotest villages. These tend to meet up with the trains, so travel is exceptionally easy. There is also train access along the Aosta Valley from Turin and Milan, with buses up the side valleys.

Getting around

There are several possibilities for using lifts during the Tour of Monte Rosa. These can be very useful for a number of reasons. If you are pressed for time, using a lift could cut off several hours of walking, and if your knees are hurting, taking a lift down could make all the difference to your comfort on the rest of the trip. Furthermore, lifts are inevitably in ski areas, and some of these look a lot better when covered in snow. So to avoid walking up or down bulldozed pistes it may be a good idea to take the lift – the ascent from Stafal (Gressoney) to the Passo dei Salati springs to mind, as does the descent from Testa Grigia to Plan Maison.

The marvellous trail leading down from Colle del Turlo on Stage 5

However, it is important to bear in mind that the lifts have a very limited open season in the summer. Typically this may be from the first week or even the second week of July to the first week of September, so if these are an integral part of your trek planning you need to be absolutely sure they will be running. If they are just an option this is less crucial, though once you’ve decided to take a lift, finding it closed can be a very traumatic experience! It’s worth knowing that some lifts have a timetable in the summer (rather than running continuously) and they tend to close for lunch or close early afternoon to fit in with summer skiing requirements.

Buses are a useful means of escape if you have to abandon the trek for some reason, or if you only plan to do a part of it. Most of the bus services mentioned in this guide are year-round regular services, but the frequency can change radically outside the high summer season. Tourist offices will have details.

Accommodation

There are a host of accommodation possibilities for your stay, ranging from hotels of all standards to an auberge or albergo (a basic hotel usually offering dormitory accommodation and maybe small rooms) to huts to campsites. In the summer season – July and August – there is a huge demand for accommodation, so advance booking is highly recommended (see Appendix C for hut contact information and Appendix D for other contacts).

Hotels

These range from 4-star luxury to no-star basic. Major towns such as Zermatt, Breuil-Cervinia and Saas Fee have many to choose from, whereas the smaller villages like St Jacques and Grächen have just a handful, usually in the 2-star category or below. In addition to rooms, some hotels also have a dormitory; this is particularly common in Switzerland. The local tourist offices will provide a list of hotels and may even make bookings for you. Note that some hotels in the Italian towns do not open before early July – this can be the case where there is a cable car (the opening time of the cable car dictates the season for the hotels).

Campsites

There are sites in most Alpine towns. Camping is generally not allowed in the valley outside campsites or (sometimes) near to the huts. Ask the tourist office for details.

Huts or refuges

Mountain huts vary greatly in the facilities they offer, from quite luxurious with showers and even small bedrooms to the most basic with just a dormitory and a dining room. There are always toilets, and running cold water is almost guaranteed, although exceptionally hot summers can lead to isolated cases of dried-up supplies. Huts high in the mountains may not have running water early in the morning when the source could be frozen, so at such huts it’s wise to fill water bottles the previous evening. Most huts are open from late June/early July to early September, and there will be a guardian in residence. Usually the guardian cooks an evening meal and provides breakfast. At a few huts you can take your own food, but you must make sure the guardian is happy with this. Quite frankly it is hardly worth the effort of carrying up food when a very good meal will be on offer for a reasonable price. Drinks – alcoholic and otherwise – are also sold.

In Italy there are strict laws about public water supplies and in some huts you may be told that the tap water is not controlled – this means they cannot guarantee that it is clean. If in doubt it’s always better to buy water than to risk being ill and unable to hike the next day.

Hut etiquette