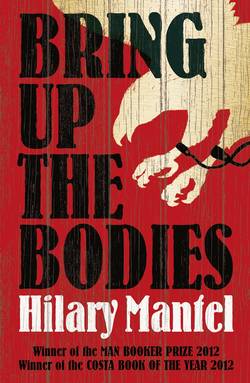

Читать книгу Bring Up the Bodies - Hilary Mantel - Страница 12

ОглавлениеChapter II Crows

London and Kimbolton, Autumn 1535

Stephen Gardiner! Coming in as he’s going out, striding towards the king’s chamber, a folio under one arm, the other flailing the air. Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester: blowing up like a thunderstorm, when for once we have a fine day.

When Stephen comes into a room, the furnishings shrink from him. Chairs scuttle backwards. Joint-stools flatten themselves like pissing bitches. The woollen Bible figures in the king’s tapestries lift their hands to cover their ears.

At court you might expect him. Anticipate him. But here? While we are still hunting through the countryside and (notionally) taking our ease? ‘This is a pleasure, my lord bishop,’ he says. ‘It does my heart good to see you looking so well. The court will progress to Winchester shortly, and I did not think to enjoy your company before that.’

‘I have stolen a march on you, Cromwell.’

‘Are we at war?’

The bishop’s face says, you know we are. ‘It was you who had me banished.’

‘I? Never think it, Stephen. I have missed you every day. Besides, not banished. Rusticated.’

Gardiner licks his lips. ‘You will see how I have spent my time in the country.’

When Gardiner lost the post of Mr Secretary – and lost it to him, Cromwell – it had been impressed on the bishop that a spell in his own diocese of Winchester might be advisable, for he had too often cut across the king and his second wife. As he had put it, ‘My lord of Winchester, a considered statement on the king’s supremacy might be welcome, just so that there can be no mistake about your loyalty. A firm declaration that he is head of the English church and, rightfully considered, always has been. An assertion, firmly stated, that the Pope is a foreign prince with no jurisdiction here. A written sermon, perhaps, or an open letter. To clear up any ambiguities in your opinions. To give a lead to other churchmen, and to disabuse ambassador Chapuys of the notion that you have been bought by the Emperor. You should make a statement to the whole of Christendom. In fact, why don’t you go back to your diocese and write a book?’

Now here is Gardiner, patting a manuscript as if it were the cheek of a plump baby: ‘The king will be pleased to read this. I have called it, Of True Obedience.’

‘You had better let me see it before it goes to the printer.’

‘The king himself will expound it to you. It shows why oaths to the papacy are of none effect, yet our oath to the king, as head of the church, is good. It emphasises most strongly that a king’s authority is divine, and descends to him directly from God.’

‘And not from a pope.’

‘In no wise from a pope; it descends from God without intermediary, and it does not flow upwards from his subjects, as you once stated to him.’

‘Did I? Flow upwards? There seems a difficulty there.’

‘You brought the king a book to that effect, the book of Marsiglio of Padua, his forty-two articles. The king says you belaboured him with them till his head ached.’

‘I should have made the matter shorter,’ he says, smiling. ‘In practice, Stephen, upwards, downwards – it hardly matters. “Where the word of a king is, there is power, and who may say to him, what doest thou?”’

‘Henry is not a tyrant,’ Gardiner says stiffly. ‘I rebut any notion that his regime is not lawfully grounded. If I were king, I would wish my authority to be legitimate wholly, to be respected universally and, if questioned, stoutly defended. Would not you?’

‘If I were king …’

He was going to say, if I were king I’d defenestrate you. Gardiner says, ‘Why are you looking out of the window?’

He smiles absently. ‘I wonder what Thomas More would say to your book?’

‘Oh, he would much mislike it, but for his opinion I do not give a fig,’ the bishop says heartily, ‘since his brain was eaten out by kites, and his skull made a relic his daughter worships on her knees. Why did you let her take the head off London Bridge?’

‘You know me, Stephen. The fluid of benevolence flows through my veins and sometimes overspills. But look, if you are so proud of your book, perhaps you should spend more time writing in the country?’

Gardiner scowls. ‘You should write a book yourself. That would be something to see. You with your dog Latin and your little bit of Greek.’

‘I would write it in English,’ he says. ‘A good language for all sorts of matters. Go in, Stephen, don’t keep the king waiting. You will find him in a good humour. Harry Norris is with him today. Francis Weston.’

‘Oh, that chattering coxcomb,’ Stephen says. He makes a cuffing motion. ‘Thank you for the intelligence.’

Does the phantom-self of Weston feel the slap? A gust of laughter sweeps out from Henry’s rooms.

The fine weather did not much outlast their stay at Wolf Hall. They had hardly left the Savernake forest when they were enveloped in wet mist. In England it’s been raining, more or less, for a decade, and the harvest will be poor again. The price of wheat is forecast to rise to twenty shillings a quarter. So what will the labourer do this winter, the man who earns five or six pence a day? The profiteers have moved in already, not just on the Isle of Thanet, but through the shires. His men are on their tail.

It used to surprise the cardinal, that one Englishman would starve another and take the profit. But he would say, ‘I have seen an English mercenary cut the throat of his comrade, and pull his blanket from under him while he’s still twitching, and go through his pack and pocket a holy medal along with his money.’

‘Ah, but he was a hired killer,’ the cardinal would say. ‘Such men have no soul to lose. But most Englishmen fear God.’

‘The Italians think not. They say the road between England and Hell is worn bare from treading feet, and runs downhill all the way.’

Daily he ponders the mystery of his countrymen. He has seen killers, yes; but he has seen a hungry soldier give away a loaf to a woman, a woman who is nothing to him, and turn away with a shrug. It is better not to try people, not to force them to desperation. Make them prosper; out of superfluity, they will be generous. Full bellies breed gentle manners. The pinch of famine makes monsters.

When, some days after his meeting with Stephen Gardiner, the travelling court had reached Winchester, new bishops had been consecrated in the cathedral. ‘My bishops’, Anne called them: gospellers, reformers, men who see Anne as an opportunity. Who would have thought Hugh Latimer would be a bishop? You would rather have predicted he would be burned, shrivelled at Smithfield with the gospel in his mouth. But then, who would have thought that Thomas Cromwell would be anything at all? When Wolsey fell, you might have thought that as Wolsey’s servant he was ruined. When his wife and daughters died, you might have thought his loss would kill him. But Henry has turned to him; Henry has sworn him in; Henry has put his time at his disposal and said, come, Master Cromwell, take my arm: through courtyards and throne rooms, his path in life is now made smooth and clear. As a young man he was always shouldering his way through crowds, pushing to the front to see the spectacle. But now crowds scatter as he walks through Westminster or the precincts of any of the king’s palaces. Since he was sworn councillor, trestles and packing cases and loose dogs are swept from his path. Women still their whispering and tug down their sleeves and settle their rings on their fingers, since he was named Master of the Rolls. Kitchen debris and clerks’ clutter and the footstools of the lowly are kicked into corners and out of sight, now that he is Master Secretary to the king. And no one except Stephen Gardiner corrects his Greek; not now he is Chancellor of Cambridge University.

Henry’s summer, on the whole, has been a success: through Berkshire, Wiltshire and Somerset he has shown himself to the people on the roads, and (when the rain isn’t bucketing down) they’ve stood by the roads and cheered. Why would they not? You cannot see Henry and not be amazed. Each time you see him you are struck afresh by him, as if it were the first time: a massive man, bull-necked, his hair receding, face fleshing out; blue eyes, and a small mouth that is almost coy. His height is six feet three inches, and every inch bespeaks power. His carriage, his person, are magnificent; his rages are terrifying, his vows and curses, his molten tears. But there are moments when his great body will stretch and ease itself, his brow clear; he will plump himself down next to you on a bench and talk to you like your brother. Like a brother might, if you had one. Or a father even, a father of an ideal sort: how are you? Not working too hard? Have you had your dinner? What did you dream last night?

The danger of a progress like this is that a king who sits at ordinary tables, on an ordinary chair, can be taken as an ordinary man. But Henry is not ordinary. What if his hair is receding and his belly advancing? The Emperor Charles, when he looks in the glass, would give a province to see the Tudor’s visage instead of his own crooked countenance, his hook nose almost touching his chin. King Francis, a beanpole, would pawn his dauphin to have shoulders like the King of England. Any qualities they have, Henry reflects them back, double the size. If they are learned, he is twice learned. If merciful, he is the exemplar of mercy. If they are gallant, he is the pattern of knight errantry, from the biggest book of knights you can think of.

All the same: in village alehouses up and down England, they are blaming the king and Anne Boleyn for the weather: the concubine, the great whore. If the king would take back his lawful wife Katherine, the rain would stop. And indeed, who can doubt that everything would be different and better, if only England were ruled by village idiots and their drunken friends?

They move back towards London slowly, so that by the time the king arrives the city will be free from suspicion of plague. In cold chantry chapels under the gaze of wall-eyed virgins, the king prays alone. He doesn’t like him to pray alone. He wants to know what he’s praying for; his old master, Cardinal Wolsey, would have known.

His relations with the queen, as the summer draws to its official end, are chary, uncertain, and fraught with distrust. Anne Boleyn is now thirty-four years old, an elegant woman, with a refinement that makes mere prettiness seem redundant. Once sinuous, she has become angular. She retains her dark glitter, now rubbed a little, flaking in places. Her prominent dark eyes she uses to good effect, and in this fashion: she glances at a man’s face, then her regard flits away, as if unconcerned, indifferent. There is a pause: as it might be, a breath. Then slowly, as if compelled, she turns her gaze back to him. Her eyes rest on his face. She examines this man. She examines him as if he is the only man in the world. She looks as if she is seeing him for the first time, and considering all sorts of uses for him, all sorts of possibilities which he has not even thought of himself. To her victim the moment seems to last an age, during which shivers run up his spine. Though in fact the trick is quick, cheap, effective and repeatable, it seems to the poor fellow that he is now distinguished among all men. He smirks. He preens himself. He grows a little taller. He grows a little more foolish.

He has seen Anne work her trick on lord and commoner, on the king himself. You watch as the man’s mouth gapes a little and he becomes her creature. Almost always it works; it has never worked on him. He is not indifferent to women, God knows, just indifferent to Anne Boleyn. It galls her; he should have pretended. He has made her queen, she has made him minister; but they are uneasy now, each of them vigilant, watching each other for some slip that will betray real feeling, and so give advantage to the one or the other: as if only dissimulation will make them safe. But Anne is not good at hiding her feelings; she is the king’s quicksilver darling, slipping and sliding from anger to laughter. There have been times this summer when she would smile secretly at him behind the king’s back, or grimace to warn him that Henry was out of temper. At other times she would ignore him, turn her shoulder, her black eyes sweeping the room and resting elsewhere.

To understand this – if it bears understanding – we must go back to last spring, when Thomas More was still alive. Anne had called him in to talk of diplomacy: her object was a marriage contract, a French prince for her infant daughter Elizabeth. But the French proved skittish in negotiation. The truth is, even now they do not fully concede that Anne is queen, they are not convinced that her daughter is legitimate. Anne knows what lies behind their reluctance, and somehow it is his fault: his, Thomas Cromwell’s. She had accused him openly of sabotaging her. He did not like the French and did not want the alliance, she claimed. Did he not shirk a chance to cross the sea for face-to-face talks? The French were all ready to negotiate, she says. ‘And you were expected, Master Secretary. And you said you were ill, and my lord brother had to go.’

‘And failed,’ he had sighed. ‘Very sadly.’

‘I know you,’ Anne said. ‘You are never ill, are you, unless you wish to be? And besides, I perceive how things stand with you. You think that when you are in the city and not at the court you are not under our eye. But I know you are too friendly with the Emperor’s man. I am aware Chapuys is your neighbour. But is that a reason why your servants should be always in and out of each other’s houses?’

Anne was wearing, that day, rose pink and dove grey. The colours should have had a fresh maidenly charm; but all he could think of were stretched innards, umbles and tripes, grey-pink intestines looped out of a living body; he had a second batch of recalcitrant friars to be dispatched to Tyburn, to be slit up and gralloched by the hangman. They were traitors and deserved the death, but it is a death exceeding most in cruelty. The pearls around her long neck looked to him like little beads of fat, and as she argued she would reach up and tug them; he kept his eyes on her fingertips, nails flashing like tiny knives.

Still, as he says to Chapuys, while I am in Henry’s favour, I doubt the queen can do me any harm. She has her spites, she has her little rages; she is volatile and Henry knows it. It was what fascinated the king, to find someone so different from those soft, kind blondes who drift through men’s lives and leave not a mark behind. But now when Anne appears he sometimes looks harassed. You can see his gaze growing distant when she begins one of her rants, and if he were not such a gentleman he would pull his hat down over his ears.

No, he tells the ambassador, it’s not Anne who bothers me; it’s the men she collects about her. Her family: her father the Earl of Wiltshire, who likes to be known as ‘Monseigneur’, and her brother George, Lord Rochford, whom Henry has appointed to his privy chamber rota. George is one of the newer staff, because Henry likes to stick with men he is used to, who were his friends when he was young; from time to time the cardinal would sweep them out, but they would seep back like dirty water. Once they were young men of esprit, young men of élan. A quarter of a century has passed and they are grey or balding, flabby or paunchy, gone in the fetlock or missing some fingers, but still as arrogant as satraps and with the mental refinement of a gatepost. And now there is a new litter of pups, Weston and George Rochford and their ilk, whom Henry has taken up because he thinks they keep him young. These men – the old ones and the new – are with the king from his uprising to his downlying, and all his private hours in between. They are with him in his stool chamber, and when he cleans his teeth and spits into a silver basin; they swab him with towels and lace him into his doublet and hose; they know his person, each mole or freckle, each bristle in his beard, and they map the islands of his sweat when he comes from the tennis court and rips off his shirt. They know more than they should, as much as his laundress and his doctor, and they talk of what they know; they know when he visits the queen to try to bounce a son into her, or when, on a Friday (the day no Christian copulates) he dreams of a phantom woman and stains his sheets. They sell their knowledge at a high price: they want favours done, they want their own derelictions ignored, they think they are special and they want you to be aware of it. Ever since he, Cromwell, came up in Henry’s service, he has been mollifying these men, flattering them, cajoling them, seeking always an easy way of working, a compromise; but sometimes, when for an hour they block him from access to his king, they can’t keep the grins from their faces. I have probably, he thinks, gone as far as I can to accommodate them. Now they must accommodate me, or be removed.

The mornings are chilly now, and fat-bellied clouds bob after the royal party as they dawdle through Hampshire, the roads turning within days from dust to mud. Henry is reluctant to hurry back to business; I wish it were always August, he says. They are en route to Farnham, a small hunting party, when a report is galloped along the road: cases of plague have appeared in the town. Henry, brave on the battlefield, pales almost before their eyes and wrenches around his horse’s head: where to? Anywhere will do, anywhere but Farnham.

He leans forward in the saddle, removing his hat as he speaks to the king. ‘We can go before our time to Basing House, let me send a fast man to warn William Paulet. Then, so as not to burden him, to Elvetham for a day? Edward Seymour is at home, and I can hunt out supplies if he is unprovided.’

He drops back, letting Henry ride ahead. He says to Rafe, ‘Send to Wolf Hall. Fetch Mistress Jane.’

‘What, here?’

‘She can ride. Tell old Seymour to put her on a good horse. I shall want her at Elvetham for Wednesday evening, any later will be too late.’

Rafe reins in, poised to turn. ‘But. Sir. The Seymours will ask why Jane and why the hurry. And why we are going to Elvetham, when there are other houses nearby, the Westons at Sutton Place …’

Drown or hang the Westons, he thinks. The Westons are no part of this plan. He smiles. ‘Say they should do it because they love me.’

He sees Rafe thinking, so my master is going to ask for Jane Seymour after all. For himself or for Gregory?

He, Cromwell, had seen at Wolf Hall what Rafe could not see: silent Jane in his bed, pale and speechless Jane, that is what Henry dreams of now. You cannot account for a man’s fantasies, and Henry is no lecher, he has not taken many mistresses. No harm if he, Cromwell, helps ease the king’s way towards her. The king does not mistreat his bedfellows. He is not a man who hates a woman once he has had her. He will write her verses, and with prompting he will give her an income, he will advance her folk; there are many families who have decided, since Anne Boleyn came up in the world, that to bask in the sunshine of Henry’s regard is an Englishwoman’s highest vocation. If they play this carefully, Edward Seymour will rise within the court, and give him an ally where allies are scarce. At this stage, Edward needs advice. Because he, Cromwell, has better business sense than the Seymours. He will not let Jane sell herself cheap.

But what will Anne the queen do, if Henry takes as mistress a young woman she has laughed at since ever Jane waited upon her: whom she calls pasty-face and milksop? How will Anne counter meekness, and silence? Raging will hardly help her. She will have to ask herself what Jane can give the king, that at present he lacks. She will have to think it through. And it is always a pleasure to see Anne thinking.

When the two parties met after Wolf Hall – king’s party and queen’s party – Anne had been charming to him, laying her hand on his arm and chattering away in French about nothing very much. As if she had never mentioned, a few weeks before, that she would like to cut off his head; as if she was only making conversation. It is well to keep behind her in the hunting field. She is keen and quick but not too accurate. This summer she put a crossbow bolt in a straying cow. And Henry had to pay off the owner.

But look, never mind all this. Queens come and go. So recent history has shown us. Let us think about how to pay for England, her king’s great charges, the cost of charity and the cost of justice, the cost of keeping her enemies beyond her shores.

From last year he has been sure of his answer: monks, that parasite class of men, are going to provide. Get out to the abbeys and convents through the realm, he had told his visitors, his inspectors: put to them the questions I will give you, eighty-six questions in all. Listen more than you speak, and when you have listened, ask to see the accounts. Talk to the monks and nuns about their lives and Rule. I am not interested where they think their own salvation lies, whether through Christ’s precious blood only or through their own works and merits in part: well, yes, I am interested, but the chief matter is to know what assets they have. To know their rents and holdings, and whether, in the event it please the king as head of the church to take back what he owns, by what mechanism it is best to do it.

Don’t expect a warm welcome, he says. They will rush to liquidate their assets ahead of your arrival. Take note of what relics they have or objects of local veneration, and how they exploit them, how much revenue they bring in by the year, for all that money is made off the back of superstitious pilgrims who would do better to stay at home and earn an honest living. Press them on their loyalty, what they think of Katherine, what they think of the Lady Mary, and how they regard the Pope; because if the mother houses of their orders are outside these shores, have they not a higher loyalty, as they might term it, to some foreign power? Put this to them and show them that they are at a disadvantage; it is not enough to assert their fidelity to the king, they must be ready to show it, and they can do that by making your work easy.

His men know better than to try to cheat him, but just to make sure he sends them out in pairs, one to watch the other. The abbeys’ bursars will offer bribes, to understate their assets.

Thomas More, in his room in the Tower, had said to him, ‘Where will you strike next, Cromwell? You are going to pull all England down.’

He had said, I pray to God, grant me life only as long as I use my power to build and not destroy. Among the ignorant it is said that the king is destroying the church. In fact he is renewing it. It will be a better country, believe me, once it is purged of liars and hypocrites. ‘But you, unless you mend your manners towards Henry, will not be alive to see it.’

Nor was he. He doesn’t regret what happened; his only regret is that More wouldn’t see sense. He was offered an oath upholding Henry’s supremacy in the church; this oath is a test of loyalty. Not many things in life are simple, but this is simple. If you will not swear it, you indict yourself, by implication: traitor, rebel. More would not swear; then what could he do but die? What could he do but splash to the scaffold, on a day in July when the torrents never stopped, except for a brief hour in the evening and that too late for Thomas More; he died with his hose wet, splashed to the knees, and his feet paddling like a duck’s. He doesn’t exactly miss the man. It’s just that sometimes, he forgets he’s dead. It’s as if they’re deep in conversation, and suddenly the conversation stops, he says something and no answer comes back. As if they’d been walking along and More had dropped into a hole in the road, a pit as deep as a man, slopping with rainwater.

You do, in fact, hear of such accidents. Men have died, the track giving way under their feet. England needs better roads, and bridges that don’t collapse. He is preparing a bill for Parliament to give employment to men without work, to get them waged and out mending the roads, making the harbours, building walls against the Emperor or any other opportunist. We could pay them, he calculated, if we levied an income tax on the rich; we could provide shelter, doctors if they needed them, their subsistence; we would all have the fruits of their work, and their employment would keep them from becoming bawds or pickpockets or highway robbers, all of which men will do if they see no other way to eat. What if their fathers before them were bawds, pickpockets or highway robbers? That signifies nothing. Look at him. Is he Walter Cromwell? In a generation everything can change.

As for the monks, he believes, like Martin Luther, that the monastic life is not necessary, not useful, not commanded of Christ. There’s nothing imperishable about monasteries. They’re not part of God’s natural order. They rise and decay, like any other institutions, and sometimes their buildings fall down, or they are ruined by lax stewardship. Over the years any number of them have vanished or relocated or become swallowed into some other monastery. The number of monks is diminishing naturally, because these days the good Christian man lives out in the world. Take Battle Abbey. Two hundred monks at the height of its fortunes, and now – what? – forty at most. Forty fat fellows sitting on a fortune. The same up and down the kingdom. Resources that could be freed, that could be put to better use. Why should money lie in coffers, when it could be put into circulation among the king’s subjects?

His commissioners go out and send him back scandals; they send him monkish manuscripts, tales of ghosts and curses, meant to keep simple people in dread. The monks have relics that make it rain or make it stop, that inhibit the growth of weeds and cure diseases of cattle. They charge for the use of them, they do not give them free to their neighbours: old bones and chips of wood, bent nails from the crucifixion of Christ. He tells the king and queen what his men have found in Wiltshire at Maiden Bradley. ‘The monks have part of God’s coat, and some broken meats from the Last Supper. They have twigs that blossom on Christmas Day.’

‘That last is possible,’ Henry says reverently. ‘Think of the Glastonbury thorn.’

‘The prior has six children, and keeps his sons in his household as waiting men. He says in his defence he never meddled with married women, only with virgins. And then when he was tired of them or they were with child, he found them a husband. He claims he has a licence given under papal seal, allowing him to keep a whore.’

Anne giggles: ‘And could he produce it?’

Henry is shocked. ‘Away with him. Such men are a disgrace to their calling.’

But these tonsured fools are commonly worse than other men; does Henry not know that? There are some good monks, but after a few years of exposure to the monastic ideal, they tend to run away. They flee the cloisters and become actors in the world. In times past our forefathers with their billhooks and scythes attacked the monks and their servants with the fury they would bring against an occupying army. They broke down their walls and threatened to burn them out, and what they wanted were the monks’ rent-rolls, the items of their servitude, and when they could get them they tore them and put them on bonfires, and they said, what we want is a little liberty: a little liberty, and to be treated like Englishmen, after the centuries we have been treated as beasts.

Darker reports come in. He, Cromwell, says to his visitors, just tell them this, and tell them loud: to each monk, one bed: to each bed, one monk. Is that so hard for them? The world-weary tell him, these sins are sure to happen, if you shut up men without recourse to women they will prey on the younger and weaker novices, they are men and it is only a man’s nature. But aren’t they supposed to rise above nature? What’s the point of all the prayer and fasting, if it leaves them insufficient when the devil comes to tempt them?

The king concedes the waste, the mismanagement; it may be necessary, he says, to reform and regroup some of the smaller houses, for the cardinal himself did so when he was alive. But surely, the great houses, we can trust them to renew themselves?

Possibly, he says. He knows the king is devout and afraid of change. He wants the church reformed, he wants it pristine; he also wants money. But as a native of the sign Cancer, he proceeds crab-wise to his objective: a side-shuffle, a weaving motion. He, Cromwell, watches Henry, as his eyes pass over the figures he has been given. It’s not a fortune, not for a king: not a king’s ransom. By and by, Henry may want to think of the larger houses, the fatter priors basted in self-regard. Let us for now make a beginning. He says, I’ve sat at too many abbots’ tables where the abbot nibbles raisins and dates, while for the monks it’s herring again. He thinks, if I had my way I would free them all to lead a different life. They claim they’re living the vita apostolica; but you didn’t find the apostles feeling each other’s bollocks. Those who want to go, let them go. Those monks who are ordained priest can be given benefices, do useful work in the parishes. Those under twenty-four, men and women both, can be sent back into the world. They are too young to bind themselves for life with vows.

He is thinking ahead: if the king had the monks’ land, not just a little but the whole of it, he would be three times the man he is now. He need no longer go cap in hand to Parliament, wheedling for a subsidy. His son Gregory says to him, ‘Sir, they say that if the Abbot of Glastonbury went to bed with the Abbess of Shaftesbury, their offspring would be the richest landowner in England.’

‘Very likely,’ he says, ‘though have you seen the Abbess of Shaftesbury?’

Gregory looks worried. ‘Should I have?’

Conversations with his son are like this: they dart off at angles, end up anywhere. He thinks of the grunts in which he and Walter communicated when he was a boy. ‘You can look at her if you like. I must visit Shaftesbury soon, I have something to do there.’

The convent at Shaftesbury is where Wolsey placed his daughter. He says, ‘Will you make a note for me, Gregory, a memorandum? Go and see Dorothea.’

Gregory longs to ask, who is Dorothea? He sees the questions chase each other across the boy’s face; then at last: ‘Is she pretty?’

‘I don’t know. Her father kept her close.’ He laughs.

But he wipes the smile from his face when he reminds Henry: when monks are traitors, they are the most recalcitrant of that cursed breed. When you threaten them, ‘I will make you suffer,’ they reply that it is for suffering they were born. Some choose to starve in prison, or go praying to Tyburn and the attentions of the hangman. He said to them, as he said to Thomas More, this is not about your God, or my God, or about God at all. This is about, which will you have: Henry Tudor or Alessandro Farnese? The King of England at Whitehall, or some fantastically corrupt foreigner in the Vatican? They had turned their heads away; died speechless, their false hearts carved out of their chests.

When he rides at last into the gates of his city house at Austin Friars, his liveried servants bunch about him, in their long-skirted coats of grey marbled cloth. Gregory is on his right hand, and on his left Humphrey, keeper of his sporting spaniels, with whom he has had easy conversation on this last mile of the journey; behind him his falconers, Hugh and James and Roger, vigilant men alert for any jostling or threat. A crowd has formed outside his gate, expecting largesse. Humphrey and the rest have money to disburse. After supper tonight there will be the usual dole to the poor. Thurston, his chief cook, says they are feeding two hundred Londoners, twice a day.

He sees a man in the press, a little bowed man, scarcely making an effort to keep his feet. This man is weeping. He loses sight of him; he spots him again, his head bobbing, as if his tears were the tide and were carrying him towards the gate. He says, ‘Humphrey, find out what ails that fellow.’

But then he forgets. His household are happy to see him, all his folk with shining faces, and a swarm of little dogs about his feet; he lifts them into his arms, writhing bodies and wafting tails, and asks them how they do. The servants cluster round Gregory, admiring him from hat to boots; all servants love him for his pleasant ways. ‘The man in charge!’ his nephew Richard says, and gives him a bone-crushing hug. Richard is a solid boy with the Cromwell eye, direct and brutal, and the Cromwell voice that can caress or contradict. He is afraid of nothing that walks the earth, and nothing that walks below it; if a demon turned up at Austin Friars, Richard would kick it downstairs on its hairy arse.

His smiling nieces, young married women now, have slackened the laces on their bodices to accommodate swelling bellies. He kisses them both, their bodies soft against his, their breath sweet, warmed by ginger comfits such as women in their condition use. He misses, for a moment … what does he miss? The pliancy of gentle, willing flesh; the absent, inconsequential conversations of early morning. He has to be careful in any dealings with women, discreet. He should not give his ill-wishers the chance to defame him. Even the king is discreet; he doesn’t want Europe to call him Harry Whoremaster. Perhaps he’d rather gaze at the unattainable, for now: Mistress Seymour.

At Elvetham Jane was like a flower, head drooping, modest as a drift of green-white hellebore. In her brother’s house, the king had praised her to her family’s face: ‘A tender, modest, shame-faced maid, such as few be in our day.’

Thomas Seymour, keen as always to crash into the conversation and talk over his elder brother: ‘For piety and modesty, I dare say Jane has few equals.’

He saw brother Edward hide a smile. Under his interested eye, Jane’s family have begun – with a certain incredulity – to sense which way the wind is blowing. Thomas Seymour said, ‘I could not brazen it out, even if I were the king I could not face it, inviting a lady like sister Jane to come to my bed. I wouldn’t know how to begin. And would you, anyway? Why would you? It would be like kissing a stone. Rolling her about from one side of the mattress to the other, and your parts growing numb from cold.’

‘A brother cannot picture his sister in a man’s embrace,’ Edward Seymour says. ‘At least, no brother can who calls himself a Christian. Though they do say at court that George Boleyn –’ He breaks off, frowning. ‘And of course the king knows how to propose himself. How to offer himself. He knows how to do it, as a gallant gentleman. As you, brother, do not.’

It’s hard to put down Tom Seymour. He just grins.

But Henry had not said much, before they rode away from Elvetham; made his hearty farewells, and never a word about the girl. Jane had whispered to him, ‘Master Cromwell, why am I here?’

‘Ask your brothers.’

‘My brothers say, ask Cromwell.’

‘So is it an utter mystery to you?’

‘Yes. Unless I am to be married at last. Am I to be married to you?’

‘I must forgo that prospect. I am too old for you, Jane. I could be your father.’

‘Could you?’ Jane says wonderingly. ‘Well, stranger things have happened at Wolf Hall. I didn’t even realise you knew my mother.’

A fleeting smile and she vanishes, leaving him looking after her. We could be married at that, he thinks; it would keep my mind agile, wondering how she might misconstrue me. Does she do it on purpose?

Though I can’t have her till Henry’s finished with her. And I once swore I would not take on his used women, did I not?

Perhaps, he had thought, I should scribble an aide-memoire for the Seymour boys, so they are clear on what presents Jane should and should not accept. The rule is simple: jewellery yes, money no. And till the deal is done, let her not take off any item of clothing in Henry’s presence. Not even, he will advise, her gloves.

Unkind people describe his house as the Tower of Babel. It is said he has servants from every nation under the sun, except Scotland; so Scots keep applying to him, in hope. Gentlemen and even noblemen from here and abroad are pressing him to take their sons into his household, and he accepts all he thinks he can train. On any given day at Austin Friars a group of German scholars will be deploying the many varieties of their tongue, frowning over the letters of evangelists from their own territories. At dinner young Cambridge men exchange snippets of Greek; they are the scholars he has helped, now come to help him. Sometimes a company of Italian merchants come in for supper, and he chats with them in those languages he learned when he worked for the bankers in Florence and Venice. The retainers of his neighbour Chapuys loll about drinking at the expense of the Cromwell buttery, and gossip in Spanish, in Flemish. He himself speaks in French to Chapuys, as it is the ambassador’s first language, and employs French of a more demotic sort to his boy Christophe, a squat little ruffian who followed him home from Calais, and who is never far from his side; he doesn’t let him far from his side, because around Christophe fights break out.

There is a summer of gossip to catch up on, and accounts to go through, receipts and expenses of his houses and lands. But first he goes out to the kitchen to see his chief cook. It’s that early-afternoon lull, dinner cleared, spits cleaned, pewter scoured and stacked, a smell of cinnamon and cloves, and Thurston standing solitary by a floured board, gazing at a ball of dough as if it were the head of the Baptist. As a shadow blocks his light, ‘Inky fingers out!’ the cook roars. Then, ‘Ah. You, sir. Not before time. We had great venison pasties made against your coming, we had to give them out to your friends before they went bad. We’d have sent some up to you, only you move around so fast.’

He holds out his hands for inspection.

‘I beg pardon,’ Thurston says. ‘But you see I have young Thomas Avery down here fresh from the account books, poking around the stores and wanting to weigh things. Then Master Rafe, look Thurston, we have some Danes coming, what can you make for Danes? Then Master Richard crashing in, Luther has sent his messengers, what sort of cakes do Germans like?’

He gives the dough a pinch. ‘Is this for Germans?’

‘Never mind what it is. If it works, you’ll eat it.’

‘Did they pick the quinces? It can’t be long before we have frost. I can feel it in my bones.’

‘Listen to you,’ Thurston says. ‘You sound like your own grandam.’

‘You didn’t know her. Or did you?’

Thurston chuckles. ‘Parish drunk?’

Probably. What sort of woman could have suckled his father Walter Cromwell, and not turned to drink? Thurston says, as if it’s just struck him, ‘Mind you, a man has two grandams. Who were your mother’s people, sir?’

‘They were northerners.’

Thurston grins. ‘Come out of a cave. You know young Francis Weston? He that waits on the king? His people are giving out that you’re a Hebrew.’ He grunts; he’s heard that one before. ‘Next time you’re at court,’ Thurston advises, ‘take your cock out and put it on the table and see what he says to that.’

‘I do that anyway,’ he says. ‘If the conversation flags.’

‘Mind you …’ Thurston hesitates. ‘It’s true, sir, you are a Hebrew because you lend money at interest.’

Mounting, in Weston’s case. ‘Anyway,’ he says. He gives the dough another nip; it’s a bit solid, is it not? ‘What’s new on the streets?’

‘They’re saying the old queen’s sick.’ Thurston waits. But his master has picked up a handful of currants and is eating them. ‘She’s sick at heart, I should think. They say she’s put a curse on Anne Boleyn, so she won’t have a boy. Or if she does have a boy, it won’t be Henry’s. They say Henry has other women and so Anne chases him around his chamber with a pair of shears, shouting she’ll geld him. Queen Katherine used to shut her eyes like wives do, but Anne’s not the same mettle and she swears he will suffer for it. So that would be a pretty revenge, wouldn’t it?’ Thurston cackles. ‘She cuckolds Henry to pay him back, and puts her own bastard on the throne.’

They have busy, buzzing minds, the Londoners: minds like middens. ‘Do they guess at who the father of this bastard will be?’

‘Thomas Wyatt?’ Thurston offers. ‘Because she was known to favour him before she was queen. Or else her old lover Harry Percy –’

‘Percy’s in his own country, is he not?’

Thurston rolls his eyes. ‘Distance don’t stop her. If she wants him down from Northumberland she just whistles and whips him down on the wind. Not that she stops at Harry Percy. They say she has all the gentlemen of the king’s privy chamber, one after another. She don’t like delay so they all stand in a line frigging their members, till she shouts, “Next.”’

‘And in they troop,’ he says. ‘One and then another.’ He laughs. Eats the final currant from his palm.

‘Welcome home,’ Thurston says. ‘London, where we believe anything.’

‘After she was crowned, I remember she called her whole household together, men and maids, and she sermonised them on how they should behave, no gambling except for tokens, no loose language and no flesh on show. It’s slid a bit from there, I agree.’

‘Sir,’ Thurston says, ‘you’ve got flour on your sleeve.’

‘Well, I must go upstairs and sit down in council. Don’t let supper be late.’

‘When is it ever?’ Thurston dusts him tenderly. ‘When is it ever?’

This is his household council, not the king’s; his familiar advisers, the young men, Rafe Sadler and Richard Cromwell, quick and ready with figures, quick to twist an argument, quick to seize a point. And also Gregory. His son.

This season young men carry their effects in soft pale leather bags, in imitation of the agents for the Fugger bank, who travel all over Europe and set the fashion. The bags are heart-shaped and so to him it always looks as if they are going wooing, but they swear they are not. Nephew Richard Cromwell sits down and gives the bags a sardonic glance. Richard is like his uncle, and keeps his effects close to his person. ‘Here’s Call-Me,’ he says. ‘Will you look at the feather in his hat?’

Thomas Wriothesley comes in, parting from his murmuring retainers; he is a tall and handsome young man with a head of burnished copper hair. A generation back, his family were called Writh, but they thought an elegant extension would give them consequence; they were heralds by office, so they were well-placed for reinvention, for the reworking of ordinary ancestors into something more knightly. The change does not go by without mockery; Thomas is known at Austin Friars as Call-Me-Risley. He has grown a trim beard recently, has fathered a son, and is accreting dignity each year. He drops his bag on the table and slides into his place. ‘And how is Gregory?’ he asks.

Gregory’s face opens in delight; he admires Call-Me, and he hardly hears the note of condescension. ‘Oh, I am well. I have been hunting all summer and now I will be back to William Fitzwilliam’s household to join in his train, for he is a gentleman close to the king and my father thinks I can learn from him. Fitz is good to me.’

‘Fitz.’ Wriothesley snorts with amusement. ‘You Cromwells!’

‘Well,’ Gregory says, ‘he calls my father Crumb.’

‘I suggest you don’t take that up, Wriothesley,’ he says amiably. ‘Or at least, Crumb me behind my back. Though I’ve just been out to the kitchens and Crumb is nothing to what they call the queen.’

Richard Cromwell says, ‘It’s the women who keep the poison pot stirred. They don’t like man-stealers. They think Anne should be punished.’

‘When we left for the progress she was all elbows,’ Gregory says, unexpectedly. ‘Elbows and points and spikes. She looks more plush now.’

‘So she does.’ He is surprised the boy has noticed such a thing. The married men, experienced, watch Anne for signs of fattening as keenly as they watch their own wives. There are glances around the table. ‘Well, we shall see. They have not been together the whole summer, but as I judge, enough.’

‘It had better be enough,’ Wriothesley says. ‘The king will grow impatient with her. How many years has he waited, for a woman to do her duty? Anne promised him a son if he would wed her, and you wonder, would he do so much for her, if it were all to do again?’

Richard Riche joins them last, with a muttered apology. No heart-shaped bag for this Richard either, though once he would have been just the kind of young gallant to have five in different colours. What a change a decade brings! Riche was once the worst kind of law student, the kind with a file of pleas in mitigation to set against his sins; the kind who seeks out low taverns where lawyers are called vermin, and so is obliged in honour to start a fight; who arrives back at his lodgings in the Temple in the small hours stinking of cheap wine and with his jacket in shreds; the kind who halloos with a pack of terriers over Lincoln’s Inn Fields. But Riche is sobered and subdued now, protégé of the Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley, and constantly to and fro between that dignitary and Thomas Cromwell. The boys call him Sir Purse; Purse is getting fatter, they say. The cares of office have fallen on him, the duties of the father of a growing family; once a golden boy, he looks to be covered by a faint patina of dust. Who would have thought he would be Solicitor General? But then he has a good lawyer’s brain, and when you want a good lawyer, he is always at hand.

‘Bishop Gardiner’s book is not to your purpose,’ Riche begins. ‘Sir.’

‘It is not wholly bad. On the king’s powers, we concur.’

‘Yes, but,’ Riche says.

‘I was moved to quote to Gardiner this text: “Where the word of a king is, there is power, and who shall say to him, what doest thou?”’

Riche raises his eyebrows. ‘Parliament shall.’

Mr Wriothesley says, ‘Trust Master Riche to know what Parliament can do.’

It was on the questions of Parliament’s powers, it seems, that Riche tripped Thomas More, tripped and tipped him and perhaps betrayed him into treason. No one knows what was said in that room, in that cell; Riche had come out, pink-faced, hoping and half-suspecting that he had got enough, and gone straight from the Tower of London to him, to Thomas Cromwell. Who had said calmly, yes, this will do; we have him, thank you. Thank you, Purse, you did well.

Now Richard Cromwell leans towards him: ‘Tell us, my little friend Purse: in your good opinion, can Parliament put an heir in the queen’s belly?’

Riche blushes a little; he is nearly forty now, but because of his complexion he can still blush. ‘I never said Parliament can do what God will not. I said it could do more than Thomas More would allow.’

‘Martyr More,’ he says. ‘The word is in Rome that he and Fisher are to be made saints.’ Mr Wriothesley laughs. ‘I agree it is ridiculous,’ he says. He darts a look at his nephew: enough now, say nothing more about the queen, her belly or any other part.

For he has confided to Richard Cromwell something at least of the events at Elvetham, at Edward Seymour’s house. When the royal party was so suddenly diverted, Edward had stepped up and entertained them handsomely. But the king could not sleep that night, and sent the boy Weston to call him from his bed. A dancing candle flame, in a room of unfamiliar shape: ‘Christ, what time is it?’ Six o’clock, Weston said maliciously, and you are late.

In fact it was not four, the sky still dark. The shutter opened to let in air, Henry sat whispering to him, the planets their only witnesses: he had made sure that Weston was out of earshot, refused to speak till the door was shut. Just as well. ‘Cromwell,’ the king said, ‘what if I. What if I were to fear, what if I were to begin to suspect, there is some flaw in my marriage to Anne, some impediment, something displeasing to Almighty God?’

He had felt the years roll away: he was the cardinal, listening to the same conversation: only the queen’s name then was Katherine.

‘But what impediment?’ he had said, a little wearily. ‘What could it be, sir?’

‘I don’t know,’ the king had whispered. ‘I don’t know now but I may know. Was she not pre-contracted to Harry Percy?’

‘No, sir. He swore not, on the Bible. Your Majesty heard him swear.’

‘Ah, but you had been to see him, had you not, Cromwell, did you not trail him to some low inn and haul him up from his bench and pound his head with your fist?’

‘No, sir. I would never so mistreat any peer of the realm, let alone the Earl of Northumberland.’

‘Ah well. I am relieved to hear that. I may have got the details wrong. But that day the earl said what he thought I wanted him to say. He said that there was no union with Anne, no promise of marriage, let alone consummation. What if he lied?’

‘On oath, sir?’

‘But you are very frightening, Crumb. You would make a man forget his manners before God. What if he did lie? What if she made a contract with Percy amounting to a lawful marriage? If that were so, she cannot be married to me.’

He had kept silence, but he saw Henry’s mind running; his own was darting like a startled deer. ‘And I much suspect,’ the king had whispered. ‘I much suspect her with Thomas Wyatt.’

‘No, sir,’ he said, vehement even before he had time to think. Wyatt is his friend; his father, Sir Henry Wyatt, had charged him to make the boy’s path smooth; Wyatt is not a boy any more, but never mind.

‘You say no.’ Henry leaned towards him. ‘But did not Wyatt avoid the realm and go to Italy, because she would not favour him and he had no peace of mind while her image was before him?’

‘Well, there you have it. You say it yourself, Majesty. She would not favour him. If she had, no doubt he’d have stayed.’

‘But I cannot be sure,’ Henry insists. ‘Suppose she denied him then but favoured him some other time? Women are weak and easily conquered by flattery. Especially when men write verses to them, and there are some who say that Wyatt writes better verses than me, though I am the king.’

He blinks at him: four o’clock, sleepless; you could call it harmless vanity, God love him, if only it were not four o’clock. ‘Majesty,’ he says, ‘put your mind at rest. If Wyatt had made any inroads on that lady’s immaculate chastity, I feel sure he could not have resisted boasting about it. In verse, or common prose.’

Henry only grunts. But he looks up: Wyatt’s well-dressed shade, silken, slides across the window, blocks the cold starlight. On your way, phantom: his mind brushes it before him; who can understand Wyatt, who absolve him? The king says, ‘Well. Perhaps. Even if she did give way to Wyatt, it would be no impediment to my marriage, there can be no question of a contract between them since he himself was married as a boy and so not free to promise anything to Anne. But I tell you, it would be impediment to my trust in her. I would not take it kindly to have any woman lie to me, and say she came a virgin to my bed if she did not.’

Wolsey, where are you? You have heard all this before. Advise me now.

He stands up. He is easing this interview to an end. ‘Shall I tell them to bring you something, sir? Something to help you sleep again for an hour or two?’

‘I need something to sweeten my dreams. I wish I knew what it was. I have consulted Bishop Gardiner in this matter.’

He had tried to keep the shock off his face. Gone to Gardiner: behind my back?

‘And Gardiner said,’ Henry’s face was the picture of desolation, ‘he said there was doubt enough in the case, but that if the marriage were not good, if I were forced to put away Anne, I must return to Katherine. And I cannot do it, Cromwell. I am resolved that even if the whole of Christendom comes against me, I can never touch that stale old woman again.’

‘Well,’ he had said. He was looking at the floor, at Henry’s large white naked feet. ‘I think we can do better than that, sir. I do not pretend to follow Gardiner’s reasoning, but then the bishop knows more canon law than me. I do not believe, however, you can be constrained or compelled in any matter, as you are master of your own household, and your own country, and of your own church. Perhaps Gardiner meant only to prepare Your Majesty for the obstacles others might raise.’

Or perhaps, he thought, he just meant to make you sweat and give you nightmares. Gardiner’s like that. But Henry had sat up: ‘I can do as it pleases me,’ his monarch said. ‘God would not allow my pleasure to be contrary to his design, nor my designs to be impeded by his will.’ A shadow of cunning had crossed his face. ‘And Gardiner himself said so.’

Henry yawned. It was a signal. ‘Crumb, you don’t look very dignified, bowing in a nightgown. Will you be ready to ride at seven, or shall we leave you behind and see you at supper?’

If you’ll be ready, I’ll be ready, he thinks, as he pads back to his bed. Come sunrise, will you forget we ever had this conversation? The court will be astir, the horses tossing their heads and sniffing the wind. By mid-morning we will be reunited with the queen’s band; Anne will be chirruping atop her hunter; she will never know, unless her little friend Weston tells her, that last night at Elvetham the king sat gazing at his next mistress: Jane Seymour ignoring his pleading eyes, and placidly working her way through a chicken. Gregory had said, his eyes round: ‘Doesn’t Mistress Seymour eat a lot?’

And now the summer is over. Wolf Hall, Elvetham, fade into the dusk. His lips are sealed on the king’s doubts and fears; it is autumn, he is at Austin Friars; with bowed head he listens to the court news, watches Riche’s fingers twisting the silk tag on a document. ‘Their households have been provoking each other in the streets,’ his nephew Richard says. ‘Thumbing of noses, curses, hands on daggers.’

‘Sorry, who?’ he says.

‘Nicholas Carew’s people. Scrapping with Lord Rochford’s servants.’

‘As long as they keep it away from the court,’ he says sharply. The penalty for drawing a blade within the precincts of the royal court is amputation of the offending hand. What is the quarrel about, he begins to ask, then changes his question: ‘What is their excuse?’

For picture Carew, one of Henry’s old friends, one of his privy chamber gentlemen, and devoted to the queen that was. See him, an antique man with his long grave face, his cultivated air of having stepped straight from a book of knight-errantry. No surprise if Sir Nicholas, with his rigid sense of the fitness of things, has found it impossible to bend to George Boleyn’s parvenu pretensions. Sir Nicholas is a papist to his steel-capped toes, and is offended to his marrow by George’s support of reformed teaching. So an issue of principle lies between them; but what trivial event has sparked the quarrel into life? Did George and his evil company make a racket outside the chamber of Sir Nicholas, while he was at some solemn business like admiring himself in the looking glass? He stifles a smile. ‘Rafe, have a word with both gentlemen. Tell them to leash their dogs.’ He adds, ‘You do right to mention it.’ He is interested, always, to hear of divisions between the courtiers and how they arose.

Soon after his sister became queen, George Boleyn had called him in and given him some instruction, about how he should handle his career. The young man was flaunting a bejewelled gold chain, which he, Cromwell, weighed in his mind’s eye; in his mind’s eye he removed George’s jacket, unstitched it, wound the fabric on to the bolt and priced it; once you have been in the cloth trade, you don’t lose your eye for texture and drape, and if you are charged with raising revenue, you soon learn to estimate a man’s worth.

Young Boleyn had kept him standing, while he occupied the room’s single chair. ‘Remember, Cromwell,’ he began, ‘that though you are of the king’s council, you are not a gentleman born. You should confine yourself to speech where it is demanded of you, and for the rest, leave it alone. Do not meddle in the affairs of those set above you. His Majesty is pleased to bring you often into his presence, but remember who it was who placed you where he could see you.’

It’s interesting, George Boleyn’s version of his life. He had always supposed it was Wolsey who trained him up, Wolsey who promoted him, Wolsey who made him the man he is: but George says no, it was the Boleyns. Clearly, he has not been expressing proper gratitude. So he expresses it now, saying yes sir and no sir, and I see you are a man of singular good judgement for your years. Why, your father Monseigneur the Earl of Wiltshire, your uncle Thomas Howard Duke of Norfolk, they could not have instructed me better. ‘I shall profit by this, I assure you sir, and from now on conduct myself more humble-wise.’

George was mollified. ‘See you do.’

He smiles now, thinking of it; returns to the scribbled agenda. His son Gregory’s eyes flit about the table, as he tries to pick up what isn’t said: now cousin Richard Cromwell, now Call-Me-Risley, now his father, and the other gentlemen who have come in. Richard Riche frowns over his papers, Call-Me fiddles with his pen. Troubled men both, he thinks, Wriothesley and Riche, and alike in some ways, sidling around the peripheries of their own souls, tapping at the walls: oh, what is that hollow sound? But he has to produce to the king men of talent; and they are agile, they are tenacious, they are unsparing in their efforts for the Crown, and for themselves.

‘One last thing,’ he says, ‘before we break up. My lord the Bishop of Winchester has so pleased the king that, at my urging, the king has sent him again to France as ambassador. It is thought his embassy will not be a short one.’

Slow smiles ripple around the table. He watches Call-Me. He was once a protégé of Stephen Gardiner. But he seems as joyful as the rest. Richard Riche turns pink, rises from the table and wrings his hand.

‘Get him on the road,’ Rafe says, ‘and let him stay away. Gardiner is double in everything.’

‘Double?’ he says. ‘He has a tongue like a three-pronged eel spear. First he is for the Pope, then Henry, then, mark what I say, he will be for the Pope again.’

‘Can we trust him abroad?’ Riche says.

‘We can trust him only to know where his advantage lies. Which is with the king for now. And we can keep an eye on him, put some of our men in his train. Master Wriothesley, you can see to that, I think?’

Only Gregory seems dubious. ‘My lord Winchester, an ambassador? Fitzwilliam tells me, an ambassador’s first duty is to give no affront.’

He nods. ‘And Stephen gives nothing but affront, does he?’

‘Is not an ambassador supposed to be a cheerful fellow and affable? So Fitzwilliam tells me. He should be pleasant in any company, conversable and easy, and he should endear himself to his hosts. So he has chances to visit their homes, sit at their boards, become friendly with their wives and their heirs, and corrupt their household to his service.’

Rafe’s eyebrows shoot up. ‘Is that what Fitz teaches you?’ The boys laugh.

‘It’s true,’ he says. ‘That is what an ambassador must do. So I hope Chapuys is not corrupting you, Gregory? If I had a wife, he would be sneaking sonnets to her, I know it, and bringing in bones for my dogs. Ah well … Chapuys, he is pleasant company, you see. Not like Stephen Gardiner. But the truth is, Gregory, we need a stout ambassador for the French, a man full of spleen and spite. And Stephen has been among them before, and done himself credit. The French are hypocrites, pretending false friendship and demanding money as the price of it. You see,’ he says, setting himself to educate his son. ‘Just now the French have a plan to take the duchy of Milan from the Emperor, and they want us to subsidise them. And we must accommodate them, or seem to, for fear they will veer about and join with the Emperor and overwhelm us. So when the day comes that they say, “Deliver over the gold you have promised,” we need that kind of ambassador, like Stephen, who will brazen it out and say, “Oh, the gold? Just take it out of what you already owe King Henry.” King Francis will be spitting fire, yet in a manner we will have kept our word. You understand? We save our fiercest champions for the French court. Recall that my lord Norfolk was sometime ambassador there.’

Gregory dips his head. ‘Any foreigner would fear Norfolk.’

‘And any Englishman too. With good reason. Now the duke is like one of those giant cannon the Turks have. The blast is shocking but it needs three hours’ cooling time before it can fire again. Whereas Bishop Gardiner, he can explode at ten-minute intervals, dawn to dusk.’

‘But sir,’ Gregory bursts out, ‘if we promise them money, and we don’t deliver it, what will they do?’

‘By then, I hope, we will be firm friends with the Emperor again.’ He sighs. ‘It is an old game and it seems we must go on playing it, until I think of something better, or the king does. You have heard of the Emperor’s recent victory at Tunis?’

‘The whole world is talking of it,’ Gregory says. ‘Every Christian knight wishes he had been there.’

He shrugs. ‘Time will tell how glorious it is. Barbarossa will soon find another base for his piracy. But with such a victory behind him, and the Turk quiet for the moment, the Emperor may turn on us and invade our shores.’

‘But how do we stop him?’ Gregory looks desperate. ‘Must we not have Queen Katherine back?

Call-Me laughs. ‘Gregory begins to perceive the difficulties of our trade, sir.’

‘I liked it better when we talked of the present queen,’ Gregory says in a low voice. ‘And I got the credit for observing she was fatter.’

Call-Me says kindly, ‘I should not laugh. You have the right of it, Gregory. All our labours, our sophistry, all our learning both acquired or pretended; the stratagems of state, the lawyers’ decrees, the churchmen’s curses, and the grave resolutions of judges, sacred and secular: all and each can be defeated by a woman’s body, can they not? God should have made their bellies transparent, and saved us the hope and fear. But perhaps what grows in there has to grow in the dark.’

‘They say that Katherine is ailing,’ Richard Riche says. ‘If she should die within the year, I wonder what world would be then?’

But look: we have sat here too long! Let’s be up and out into the gardens of Austin Friars, Master Secretary’s pride; he wants the plants he saw flowering abroad, he wants better fruit, so he nags the ambassadors to send him shoots and cuttings in the diplomatic bag. The keen young clerks stand by, ready to break a code, and all that tumbles out is a rootball, still pulsing with life after a journey through the straits of Dover.

He wants tender things to live, young men to thrive. So he has built a tennis court, a gift to Richard and Gregory and all the young men of his house. He is not quite beyond the game himself … if he could play a blind man, he says, or an opponent with one leg. Much of the game is tactics; his foot drags, he has to rely on cunning rather than speed. But he is proud of his building and glad to stand the expense. He has recently consulted with the king’s keepers of tennis at Hampton Court, and had the measurements adjusted to those Henry prefers; the king has been to Austin Friars to dine, so it is not unpossible that one day he may call in for an afternoon on the court.

In Italy, when he was a servant in Frescobaldi’s household, the boys would go out in the hot evening and play games in the street. It was tennis of a kind, a jeu de paume, no racquets but just the hand; they would jostle and push and scream, bounce the ball off the walls and run it along a tailor’s awning, till the master himself would come out and scold: ‘If you boys don’t respect my awning, I’ll shear off your testicles and hang them over the doorway on a ribbon.’ They would say sorry, master, sorry, and back off down the street, and play subdued in a back court. But half an hour later they would be back again, and he can still hear it in his dreams, the rattle as the ball’s crude seam hit metal and skimmed into the air; he can feel the slap of leather against his palm. In those days, though he was carrying an injury he tried to run the stiffness off: this injury he’d got the other year, when he was at Garigliano with the French army. The garzoni would say, look Tommaso, how is it you got the wound in the back of the leg, were you running away? He would say, Mother of God, yes: I was only paid enough for running away, if you want me facing the front you have to pay me extra.

From this massacre the French scattered, and in those days he was French; the King of France paid his wages. He had crawled then limped, he and his comrades dragging their battered bodies as fast as they could from the victorious Spanish, trying to struggle back to ground not bogged with blood; they were wild Welsh bowmen and renegade Switzers, and a few English boys like himself, all of them more or less confused and penniless, gathering their wits in the aftermath of the rout, plotting a course, changing their nation and their names at need, washing up in the cities to the north, looking for the next battle or some safer trade.

At the back gate of a great house, a steward had interrogated him: ‘French?’

‘English.’

The man had rolled his eyes. ‘So what can you do?’

‘I can fight.’

‘Evidently, not well enough.’

‘I can cook.’

‘We have no need of barbarous cuisine.’

‘I can cast accounts.’

‘This is a banking house. We are well supplied.’

‘Tell me what you want done. I can do it.’ (Already he boasts like an Italian.)

‘We want a labourer. What is your name?’

‘Hercules,’ he says.

Against his better judgement, the man laughs. ‘Come in, Ercole.’

Ercole limps in, over the threshold. The man bustles about his own duties. He sits down on a step, nearly weeping with pain. He looks around him. All he has is this floor. This floor is his world. He is hungry, he is thirsty, he is over seven hundred miles from home. But this floor can be improved. ‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph!’ he shouts. ‘Water! Bucket! Allez, allez!’

They go. Quick they go. A pail arrives. He improves this floor. He improves this house. He does not improve it without resistance. They start him off in the kitchen, where as a foreigner he is ill-received, and where with the blades and spits and boiling water there is so much possibility for violence. But he is better at fighting than you would think: lacking in height, without skill or craft, but almost impossible to knock over. And what aids him is the fame of his countrymen, feared through Europe as brawlers and looters and rapists and thieves. As he cannot abuse his colleagues in their own language, he uses Putney. He teaches them terrible English oaths – ‘By the bleeding nail-holes of Christ’ – which they can use to relieve their feelings behind the backs of their masters. When the girl comes in the mornings, the herbs in her basket damp with dew, they step back, appreciate her and ask, ‘Well, sweetheart, and how are you today?’ When somebody interrupts a tricky task, they say, ‘Why don’t you fuck off out of here, or I’ll boil your head in this pot.’

Before long he understood that fortune had brought him to the door of one of the city’s ancient families, who not only dealt in money and silk, wool and wine, but also had great poets in their lineage. Francisco Frescobaldi, the master, came to the kitchen to talk to him. He did not share the general prejudice against Englishmen, rather he thought of them as lucky; although, he said, some of his ancestors had been brought close to ruin by the unpaid debts of kings of England long ago dead. He had little English himself and he said, we can always use your countrymen, there are many letters to write; you can write, I hope? When he, Tommaso or Ercole, had improved in Tuscan so much that he was able to express himself and make jokes, Frescobaldi had promised, one day I will call you to the counting house. I will make trial of you.

That day came. He was tried and he won. From Florence he went to Venice, to Rome: and when he dreams of those cities, as sometimes he does, a residual swagger trails him into his day, a trace of the young Italian he was. He thinks back to his younger self with no indulgence, but no blame either. He has always done what was needed to survive, and if his judgement of what was necessary was sometimes questionable … that is what it is to be young. Nowadays he takes poor scholars into his family. There’s always a job for them, some niche where they can scribble away at tracts on good government or translations of the psalms. But he will also take in young men who are rough and wild, as he was rough and wild, because he knows if he is patient with them they will be loyal to him. Even now, he loves Frescobaldi like a father. Custom stales the intimacies of marriage, children grow truculent and rebel, but a good master gives more than he takes and his benevolence guides you through your life. Think of Wolsey. To his inner ear, the cardinal speaks. He says, I saw you, Crumb, when you were at Elvetham: scratching your balls in the dawn and wondering at the violence of the king’s whims. If he wants a new wife, fix him one. I didn’t, and I am dead.

Thurston’s cake must have failed because it doesn’t appear that evening at supper, but there is a very good jelly in the shape of a castle. ‘Thurston has a licence to crenellate,’ Richard Cromwell says, and immediately throws himself into a dispute with an Italian across the table: which is the best shape for a fort, circular or star-shaped?

The castle is made in stripes of red and white, the red a deep crimson and the white perfectly clear, so the walls seem to float. There are edible archers peeping from the battlements, shooting candied arrows. It even makes the Solicitor General smile. ‘I wish my little girls could see it.’

‘I’ll send the moulds to your house. Though perhaps not a fort. A flower garden?’ What pleases little girls? He’s forgotten.

After supper, if there are no messengers pounding at the door, he will often steal an hour to be among his books. He keeps them at all his properties: at Austin Friars, at the Rolls House at Chancery Lane, at Stepney, at Hackney. There are books these days on all sorts of subjects. Books that advise you how to be a good prince, or a bad one. Poetry books and volumes that tell you how to keep accounts, books of phrases for use abroad, dictionaries, books that tell you how to wipe your sins clean and books that tell you how to preserve fish. His friend Andrew Boorde, the physician, is writing a book on beards; he is against them. He thinks of what Gardiner said: you should write a book yourself, that would be something to see.

If he did, it would be The Book Called Henry: how to read him, how to serve him, how best to preserve him. In his mind he writes the preamble. ‘Who shall number the qualities, both public and private, of this most blessed of men? Among priests, he is devout: among soldiers, valiant: among scholars, erudite: among courtiers, most gentle and refined: and all these qualities, King Henry possesses in such a remarkable degree that the like was never seen since the world began.’

Erasmus says that you should praise a ruler even for qualities he does not have. For the flattery gives him to think. And the qualities he presently lacks, he might go to work on them.

He looks up as the door opens. It is his little Welsh boy, backing in: ‘Ready for your candles, master?’

‘Yes, more than ready.’ The light shivers, then settles against dark wood like discs pared from a pearl. ‘You see that stool,’ he says. ‘Sit on it.’

The boy flops down. The demands of the household have had him on the run since early morning. Why is it always little legs that have to save big legs? Just run upstairs and fetch me … It flattered you, when you were young. You thought you were important, indeed essential. He used to hurtle around Putney, on errands for Walter. More fool him. Now it pleases him to say to a boy, take your ease. ‘I used to speak a bit of Welsh when I was a boy. I can’t now.’

He thinks, that’s the bleat of the man of fifty: Welsh, tennis, I used to, I can’t now. There are compensations: the head is better stored with information, the heart better proof against chips and fractures. Just now he is undertaking a survey of the queen’s Welsh properties. For this and weightier reasons, he keeps a keen eye on the principality. ‘Tell me your life,’ he asks the child. ‘Tell me how you came here.’ With the boy’s own bit of English, he pieces together his tale: arson, cattle raids, the usual borderlands story, ending in destitution, the making of orphans.

‘Can you say the Pater Noster?’ he asks.

‘Pater Noster,’ says the boy. ‘Or, Our Father.’

‘In Welsh?’

‘No, sir. There are no prayers in Welsh.’

‘Dear Jesus. I’ll get a man on it.’

‘Do, sir. Then I can pray for my father and mother.’

‘Do you know John ap Rice? He was at supper with us tonight.’

‘Married to your niece Johane, sir?’

The boy darts off. Little legs at work again. It’s his aim that all the Welsh will speak English, but that can’t be yet, and meanwhile they need God on their side. Brigands cover the whole principality, and bribe and threaten their way out of gaol; pirates savage the coasts. Those gentlemen with territory there, like Norris and Brereton of the king’s privy chamber, seem resistant to his interest. They put their own dealings before the king’s peace. They do not care to have their activities overseen. They do not care for justice: whereas he means to make an equal justice, from Essex to Anglesey, Cornwall to the Scots border.

Rice brings in with him a little velvet box, which he puts down on the desk: ‘Present. You have to guess.’

He rattles it. Something like grains. His finger explores fragments, scaly, grey. Rice has been surveying abbeys for him. ‘It wouldn’t be St Apollonia’s teeth?’

‘Guess again.’

‘Is it teeth from the comb of Mary Magdalene?’

Rice relents. ‘St Edmund’s nail parings.’

‘Ah. Tip them in with the rest. The man must have had five hundred fingers.’

In the year 1257, an elephant died in the Tower menagerie and was buried in a pit near the chapel. But the following year he was dug up and his remains sent to Westminster Abbey. Now, what did they want at Westminster Abbey, with the remains of an elephant? If not to carve a ton of relics out of him, and make his animal bones into the bones of saints?

According to the custodians of holy relics, part of the power of these artefacts is that they are able to multiply. Bone, wood and stone have, like animals, the ability to breed, yet keep their intact nature; the offspring are in no wise inferior to the originals. So the crown of thorns blossoms. The cross of Christ puts out buds; it flourishes, like a living tree. Christ’s seamless coat weaves copies of itself. Nails give birth to nails.

John ap Rice says, ‘Reason cannot win against these people. You try to open their eyes. But ranged against you are statues of the virgin that weep tears of blood.’

‘And they say I play tricks!’ He broods. ‘John, you must sit down and write. Your compatriots must have prayers.’

‘They must have a Bible, sir, in their own tongue.’

‘Let me first get the king’s assured blessing for the English to have it.’ It is his daily, covert crusade: for Henry to sponsor a great Bible, put it in every church. He is very close now and he thinks he can win Henry to it. His ideal would be a single country, single coinage, just one method of weighing and measuring, and above all one language that everybody owns. You don’t have to go to Wales to be misunderstood. There are parts of this realm not fifty miles from London, where if you ask them to cook you a herring they give you a blank look instead. Only when you’ve pointed to the pan and impersonated a fish do they say, ah, now I see what you mean.

But his greatest ambition for England is this: the prince and his commonwealth should be in accord. He doesn’t want the kingdom to be run like Walter’s house in Putney, with fighting all the time and the sound of banging and shrieking day and night. He wants it to be a household where everybody knows what they have to do, and feels safe doing it. He says to Rice, ‘Stephen Gardiner says I should write a book. What do you think? Perhaps I might if one day I retire. Till then, why should I give my secrets away?’