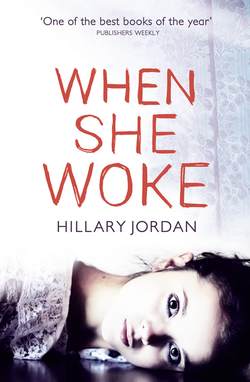

Читать книгу When She Woke - Hillary Jordan - Страница 8

ОглавлениеSHE TRIED TO GO BACK TO sleep, but the white light burned through her closed lids, through her eyeballs and into her brain. Even with an arm flung over her eyes, she could still see it, like a harsh alien sun blazing inside her skull. This was by design, she knew. The lights inhibited sleep in all but a small percentage of inmates. Of these, something like ninety percent committed suicide within a month of their release. The message of the numbers was unambiguous: if you were depressed enough to sleep despite the lights, you were as good as dead. Hannah couldn’t sleep. She didn’t know whether to be relieved or disappointed.

She shifted onto her side. She couldn’t feel the microcomputers embedded in the pallet, but she knew they were there, monitoring her temperature, pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, white blood cell count, serotonin levels. Private information—but there was no privacy in a Chrome ward.

She needed to use the toilet but held it for as long as possible, mindful of the cameras. While “acts of personal hygiene” were censored from public broadcast, she knew the guards and editors still saw them. Finally, when she could wait no longer, she got up and peed. The urine came out yellow. There was some comfort in that.

At the sink she found a cup and toothbrush. She opened her mouth to clean her teeth and was startled by the sight of her tongue. It was a livid reddish purple, the color of a raspberry popsicle. Only her eyes were unchanged, still a deep black, surrounded by white. The virus no longer mutated the pigment of the eyes as it had in the early days of melachroming. There’d been too many cases of blindness, and that, the courts had decided, constituted cruel and unusual punishment. Hannah had seen vids of those early Chromes, with their flat neon gazes and disturbingly blank faces. At least she still had her eyes to remind her of who she was: Hannah Elizabeth Payne. Daughter of John and Samantha. Sister of Rebecca. Killer of a child, unnamed. Hannah wondered whether that child would have inherited its father’s melancholy brown eyes and sensitive mouth, his high wide brow and translucent skin.

Her own skin felt clammy, and her body smelled sour. She went to the shower unit. A sign on the door read: WATER NONPOTABLE. DO NOT DRINK. Just beneath it was a hook for her shift. She started to take it off but then remembered the watchers and stepped inside still wearing it. She closed the door, and the water came on, blessedly hot. There was a dispenser of soap and she used it, scrubbing her skin hard with her hands. She waited until the walls of the shower steamed up and then lifted up her shift and quickly soaped and rinsed herself underneath. As always, the feel of hair under her arms surprised her, though she should have been used to it by now. She hadn’t been allowed a lazor since her arrest. At first, when the hair there and on her legs had begun to grow out, going from stubbly to silky, it had horrified her. Now, the thought of such feminine vanity made her laugh, an ugly sound, loud in the enclosed space of the stall. She was a Red. Her femininity was irrelevant.

She remembered the first time she’d seen a female Chrome, when she was in kindergarten. Then as now, they were comparatively rare, and the vast majority were Yellows serving short sentences for misdemeanors. The woman Hannah had seen was a Blue—an even more uncommon sight, though she was too young then to know it. Child molesters tended not to survive long once they were released. Some committed suicide, but most simply disappeared. Their bodies turned up in dumpsters and rivers, stabbed or shot or strangled. That day, Hannah and her father had been crossing the street, and the woman, swathed in a long, hooded coat and gloves despite the sticky autumn heat, had been crossing in the opposite direction. As she approached, Hannah’s father jerked Hannah toward him, and the sudden motion caused the woman to lift her lowered head. Her face was a startling cobalt blue, but it was her eyes that riveted Hannah. They were like shards of basalt, jagged with rage. Hannah shrank away from her, and the woman smiled, baring white teeth planted in ghastly purple gums.

Hannah hadn’t quite finished rinsing herself when the water brake activated. The dryjets came on, and warm air whooshed over her. When they cut off, she stepped out of the shower, feeling a little better for being clean.

The tone sounded three times and the food panel opened. Hannah ignored it. But it seemed she wouldn’t be allowed to skip another meal, because after a short delay a different tone sounded, this one a needle-sharp, intolerable shriek. She walked quickly to the opening in the wall and removed the tray. The sound stopped.

There were two nutribars, one a speckled brown, the other bright green, as well as a cup of water and a large beige pill. It looked like a vitamin, but she couldn’t be sure. She ate the bars, leaving the pill, and returned the tray to the opening. But as she turned away, the shrieking started again. She picked up the pill and swallowed it. The sound stopped and the panel slid shut.

Now what? Hannah thought. She looked despairingly around the featureless cell, wishing for something, anything to distract her from the sight of herself. In the infirmary, just before they’d injected her with the virus, the warden had offered her a Bible, but his pompous, self-righteous manner and disdainful tone had kept her from taking it. That, and her own pride, which had prompted her to say, “I don’t want anything from you.”

He smirked. “You won’t be so high and mighty after a week or two alone in that cell. You’ll change your mind, just like they all do.”

“You’re wrong,” she said, thinking, I’m not like the others.

“When you do,” the warden went on, as if Hannah hadn’t spoken, “just ask, and I’ll see to it you get one.”

“I told you, I won’t be asking.”

He eyed her speculatively. “I give you six days. Seven, tops. Don’t forget to say please.”

Now, Hannah kicked herself for not having accepted that Bible. Not because she would find any comfort in its pages—God had clearly abandoned her, and she couldn’t blame Him—but because it would have given her something to contemplate besides the red ruin she’d made of her life. She leaned back against the wall and slid down it until her buttocks touched the floor. She hugged her knees and rested her head on top of them, but then saw the pitiful, little-match-girl picture she made in the mirror and straightened up, crossing her legs and folding her hands in her lap. There was no way to tell when she was on. Although the feed from each cell was continuous and the broadcasts were live, they didn’t show every inmate all the time, but rather, shuffled among them at the discretion of the editors and producers. Hannah knew she was just one of thousands they had to choose from in the central time zone alone, but from the few times she’d watched the show she also knew that women, especially the attractive ones, tended to get more airtime than men, and Reds and other felons more than Yellows. And if you were one of the really entertaining ones—if you spoke in tongues or had conversations with imaginary people, if you screamed for mercy or had fits or scraped your skin raw trying to get the color off (which was allowed only to a point, and then the punishment tone would sound)—you could be bumped up to the national show. She vowed to present as calm and uninteresting a picture as possible, if only for her family’s sake. They could be watching her at this moment. He could be watching.

He hadn’t come to the trial, but he’d appeared via vidlink at her sentencing hearing. A holo of his famous face had floated in front of her, larger than life, urging her to cooperate with the prosecutors. “Hannah, as your former pastor, I implore you to comply with the law and speak the name of the man who performed the abortion and any others who played a part.”

Hannah couldn’t bring herself to look at him. Instead, she watched the attorneys and court officials, spectators and jurors as they listened to him, leaning forward in their seats to catch his every word. She watched her father, who sat hunched in his Sunday suit and hadn’t met her eyes since the bailiff had led her into the courtroom. Of course, her mother and sister weren’t with him.

“Don’t be swayed by mistaken loyalty or pity for your accomplices,” the reverend went on. “What can your silence do for them, except encourage them to commit further crimes against the unborn?” His voice, low and rich and roughened by emotion, rolled through the room, commanding the absolute attention of everyone present. “By the grace of God,” he said, on a rising note, “you’ve been granted an open shame, so that you may one day have an open triumph over the wickedness within you. Would you deny your fellow sinners the same bitter but cleansing cup you now drink from? Would you deny it to the father of this child, who lacked the courage to come forward? No, Hannah, better to name them now and take from them the intolerable burden of hiding their guilt for the rest of their lives!”

The judge, jury, and spectators turned to Hannah expectantly. It seemed impossible that she could resist the power of that impassioned appeal. It came, after all, from none other than the Reverend Aidan Dale, former pastor of the twenty-thousand-member Plano Church of the Ignited Word, founder of the Way, Truth & Life Worldwide Ministry and now, at the unheard-of age of thirty-seven, newly appointed secretary of faith under President Morales. How could Hannah not speak the names? How could anyone?

“No,” she said. “I won’t.”

The spectators let out a collective sigh. Reverend Dale placed his hand on his chest and lowered his head, as though in silent prayer.

“Miss Payne,” said the judge, “has your counsel made you aware that by refusing to testify as to the identities of the abortionist and the child’s father, you’re adding six years to your sentence?”

“Yes,” she replied.

“Will the prisoner please rise.”

Hannah felt her attorney’s hand on her elbow, helping her to stand. Her legs wobbled and her mouth was dry with dread, but she kept her face expressionless.

“Hannah Elizabeth Payne,” began the judge.

“Before you sentence her,” interrupted Reverend Dale, “may I address the court once more?”

“Go ahead, Reverend.”

“I was this woman’s pastor. Her soul was in my charge.” She looked at him then, meeting his gaze. The pain in his eyes tore at her heart. “That she’s sitting before this court today isn’t just her fault, but mine as well, for failing to guide her toward righteousness. I’ve known Hannah Payne for two years. I’ve seen her devotion to her family, her kindness to those less fortunate, her true faith in God. Though her crime is grave, I believe that through His grace she can be redeemed, and I’ll do everything in my power to help her, if you’ll show her leniency.”

Among the jury, heads nodded and eyes misted. Even the judge’s stern countenance softened a bit. Hannah began to have hope. But then he shook his head sharply, as if he were dispelling an enchantment, and said, “I’m sorry, Reverend. The law is absolute in these cases.”

The judge turned back to her. “Hannah Elizabeth Payne, having been found guilty of the crime of murder in the second degree, I hereby sentence you to undergo melachroming by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, to spend thirty days in the Chrome ward of the Crawford State Prison and to remain a Red for a period of sixteen years.”

When he banged the gavel she swayed on her feet but didn’t fall. Nor did she look at Aidan Dale as the guards led her away.