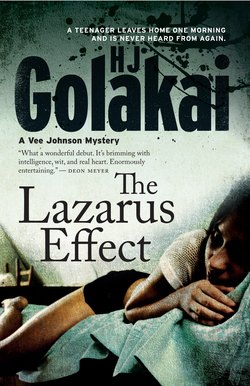

Читать книгу The Lazarus Effect - HJ Golakai - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Six

Оглавление“You sure you don’t want something to eat?”

Vee drained her cup of Ovaltine and ahh-ed in satisfaction as she shook her head in refusal. Agreeing to supper would mean having to wait until it was prepared, and neither she nor her best friend were up to that. There was bound to be something reheatable in her fridge.

After a stop to refuel, she’d acted on a hankering for a more bustling environment than her own sitting room. She sometimes liked to think in noisy or alien surroundings, and Connie Adeyemo’s flat in Rondebosch was rarely a disappointment. Her younger sister Suwa moaned about money problems to an unappreciative world at large as Jeremy bounced around, refusing to be put to bed. Amid all this, Connie did a quick stock-take with her two employees while Vee soaked it all in. Being an abusive employer took a lot of Connie’s time, and often involved overtime holding court with her staff and chewing them out for incompetence. As she was the successful owner of one of the most select West African boutiques in the Claremont area, something had to be said for her methods.

“Thanks again for taking him to paeds for that chest cold,” Connie said when the place was emptied and restful. She reached over and stroked her son’s back as he slept on Vee’s lap. “I waited two weeks for that appointment, and Suwa couldn’t leave classes to do it. If I’d lost it, hayy!” She pushed out her mouth in contempt at the prospect. “That WI is elitist.”

“Ay, my sister, you tellin’ me,” Vee agreed. She knew the next question would be whether she’d made her appointment, followed by a lecture on gross irresponsibility that she hadn’t, so she continued with: “Guess who I bumped into this evening by Pick n Pay?”

Connie read her expression and broke into a grin. “Hmm, it’s a small town for sure. You two on this merry-go-round! What did he say? Did he look nice?”

“He looked like a shoeshine boy with a thriving sidewalk business.”

They burst into hearty laughter before Connie pressed: “You seeing him again anytime?”

“On that note . . .” Vee scooped the child up gingerly and made for the bedroom.

Her friend smirked. “Yes, Jeremy, go and sleep. So your auntie can run from my questions. She thinks she can get very far running from the truth on those her long legs.”

Vee stuck her tongue out at her. “Ikenna, you see that your mother? She can never mind her own business,” she whispered to her sleeping godson. “Likes to pretend she’s a white woman, calling you ‘Jeremy’ instead of your real name. Sellout. Please ask her if she got permission from your Igbo father who named you himself before she started calling you fwehn-fwehn. Let her answer that one first.”

Connie laughed once more. “Leave my house, oh, rubbish girl!”

After Vee left, she made straight for home. A quiet evening with a full belly was what she now craved, preferably in a dark room where she could zone out uninterrupted.

She wasn’t surprised at running into Joshua Allen on the street. Her reaction to seeing him was the surprise; she’d almost forgotten how uplifting it was to see another friendly face who knew her unfriendly past. Over the four years she’d known him, his exterior hadn’t changed at all. Height and build perfect for swimming or track, but wasted on a joker who refused to take any sport seriously for long. Dark, sloe-shaped eyes that carried his finest of smiles. That infuriating shit-eating grin when he could be bothered. Today typified the Allen ambiance, materialising in the form of a soggy pile of crap next to a nameless beautiful woman.

Oh my God, he’s thirty, Vee thought suddenly. About five weeks ago. Time was growing him up. It was depressing to think that their lives had been, and would keep on, careening down chaotic paths, while in many ways they were as prepared for it as children. Broken dolls all of them. Joshua had first come to Cape Town on a quest for the Holy Grail, the unattainable ideal of a complete family. She’d come to follow her heart. Fat lot of good the pursuit had done either of them. Their faith in the picture-perfect was now irreparably injured.

His mother was an African-American history professor who had fallen for a Hindu anti-apartheid activist exiled in the USA. Together they’d had a son. When the democratic tide turned against the apartheid regime, the exiles began to trickle home. His old man returned, married respectably within the Indian community and time withered the American connection. Joshua was six when his father returned to South Africa for good.

Armed with a predisposition for closure, Joshua had boarded a plane in his early twenties. He’d had no expectations of a happy reunion, and hadn’t gotten one. The final slap in the face came when an uninterested family on the African continent refused to acknowledge his existence and a loving one in America kindly told him to bury the past for peace of mind. Older and wiser, he’d now relocated to South Africa because he was drawn to it and wanted to stop finding excuses to visit. He would never admit it, but Vee knew he still drew secret pleasure from the proximity to his father. Playing the hovering nightmare, the illegitimate pin itching to burst the well-constructed bubble of his father’s life, appealed to Joshua’s devilish side.

Vee idled the engine at a red traffic light, battling a fresh rush of dejection. The feelings of sadness and anger brought about by Joshua Allen’s reappearance came from the memory of how she’d come into her current predicament. If she was being completely unfair – and driving alone in her own car on a cold winter evening allowed her to do whatever the hell she wanted – then she could say that in a roundabout way it was all Joshua Allen’s fault. He was friends with Titus Wreh, and Titus Wreh had broken her heart into a million pieces. Had Joshua not been living in South Africa, maybe neither she nor Titus would have decided to leave New York, which had spelled the beginning of the end of their relationship.

Fine, it was a stretch and even she knew it. Titus had been looking for a new job and a change of scene – mainly to leave the United States. Dealing with New York City and family business can make a person jaded; Titus had had his fill and wanted to break out on his own. A Liberian-American hybrid, Titus talked of “going home”, although since he had lived three-quarters of his life in the US, Vee wondered which home he meant and if he fully appreciated what it consisted of. She was near the end of her degree, the world was her oyster and Vee hadn’t minded either way. She’d landed a temporary position with an independent news agency to complement Titus’s new job with Deloitte and they’d packed their bags.

Months later, she was engaged and seeing out the final weeks of her contract. She hadn’t thought about lining up a more permanent position or even if she wanted one after she was married, that is, if she really wanted to be married at all. It turned out she hadn’t thought about a lot of things, and life had a way of making hard choices on your behalf. Stretched to the limit by freelancing and planning a wedding, she passed out in extreme pain one sunny afternoon and woke up post-surgery minus a foetus and a chunk of an ovary.

The emergency procedure had been performed to remedy an ectopic pregnancy she hadn’t been aware of. It had also uncovered an ovarian cyst, a complication. Under pressure, Titus, appointed next of kin, gave consent for the surgery after consultation with the doctors. He later interpreted her withdrawal from him to be anger, that she secretly blamed and despised him for making the decision on her behalf. After the trauma of the miscarriage and operation, she’d crumbled. Soon after, so did their relationship.

Her friends and relatives postulated depression, saying that all had been too huge a blow. The gossips accused her of wallowing in aimless self-pity and lacking the nerve to stop her life from crumbling around her ears. They were all very wrong and yet very right. Semi-conscious, she watched as an engagement ended and job offers dried up, and friends stopped plying her with platitudes and financial tide-overs. Eventually, self-preservation won out, and she hobbled back towards the light. A girl’s gotta eat.

“What am I ’sposed to say when I’m all choked up and you’re okay? I’m falling to piiieeeces yeah,” crooned Danny O’Donoghue of The Script, his heart breaking unevenly all over 5FM radio.

“I hear you, my friend,” Vee muttered, switching it off. Nearly everyone was stronger than they gave themselves credit for, but hardly anyone wanted to suffer through finding out exactly what they were made of. Based on past experience, she knew she could survive the blizzard of blows that had rained on both her personal and professional life in the past eighteen months. She’d been through worse. But had anyone told her she’d also have to soldier through the past six months of heartache and confusion without the man she thought was her life, she’d have laughed in their faces. Every hurt dug that much deeper into her flesh without Titus by her side.

Twenty-seven had been young. It had been the start of life in this country and had the nerve to still be dreamy, dumb and very young. Twenty-seven was only a hop, skip and jump from twenty-nine, but had involved far too much exertion. Falling down. Walking in the same spot. Blood, sweat and tears. Twenty-nine, when it rolled around in a month, would be wiser. And more bitter, lonely and sexually frustrated. Definitely poorer. Thirty and beyond was bound to be a roaring hussy with venereal disease.

The Toyota slid into the garage, and she slammed the door on exit, hoping to bring her dog running. It was a blessing to have a place all her own. The tiny household had begun with two occupants, and she’d gotten stuck with the smaller bedroom and on-street parking. Mia had been a great girl, with wild blonde hair and spiritual-guru leanings, but time had revealed her to be about ninety degrees short of a right angle. Never had Vee met another person less suited to the sane and standard rules of cohabitation. Every five minutes some new force channelled through Mia’s being, fuelling stranger and stranger antics. When she consigned herself to a strict sushi diet, acquired two snobby cats called Ginger and Wasabi and went around breathing soy sauce fumes at people all day, Vee had had enough.

Luckily, Mia was a peaceful soul who shunned confrontation. She noticed Vee’s energy pulsed with an edge of resentment, and to preserve the friendship had decided to move to Observatory. Now the big bedroom was all Vee’s, as were the small bedroom (study-library) and the parking space and the crooked tree in the tiny square of garden with the braai stand and the orange picket fence. The rent was all hers, too.

She removed two items from the postbox without bothering to look them over. It was nearly dark, and her gut was snarling. The good folks of suburban Claremont were already parked inside their fences, another working day over. A shiny luxury vehicle lounged a little too close to her gate, and she made a mental note to ask that her neighbour abide by the parking restrictions when he bought new toys.

Inside, she dumped bag and laptop on the nearest counter, and without switching on any lights opened the fridge. Milk. Water. Leftover fragments of fried fish gravy, jollof rice and sweet potatoes. Bread and Windhoek lager. Fresh salad ingredients. Vee scratched her nose and popped the freezer compartment. Free-range chicken and prime beef cuts. She closed both doors, paused in the dark and then sniffed. Asian food. No dog.

“You want another beer?” she called out to the emptiness.

“Nah, I’m good, just opened this one,” a male voice called back.

She grabbed a bottle and headed for the lounge, still not flipping any switches. Criminals were best confronted in the dark.

“Didn’t I warn you to stop breaking into my house?”

Through the open curtains, enough light filtered from the street to reveal Joshua’s grin as she took a seat. The black husky near his feet didn’t budge, but offered swishes of the tail in welcome. Treachery and deceit in her own home. Males always stuck together.

“Come on, don’t act like you’re not happy to see me again. Besides, breaking and entering’s a skill I learned from the best.” He tipped his beer at her in salute. “Like all skills, if you don’t put it to use it rots away. Hungry?”

Vee was already munching gratefully on a mouthful of Thai noodles. It was very good. Too good to be cheap takeaway. It was better not to ask.

“I don’t taste any meat in this.” She stirred the aromatic mix accusingly with the chopsticks. “There’s no meat? It’s meat-free?”

Joshua shook his head and chuckled. “That’s mine. Yours is in the microwave.”

When seated again and blowing steam off her supper, she said: “Don’t park your capitalist monstrosity of a car so close to my driveway. I could hardly squeeze past it. How am I supposed to back out?”

“I’ll be long gone before it comes to that. Or you asking me to spend the night?”

“Dream on. And for your information, I don’t keep bread in the fridge. Or buy pinot noir. And free-range chicken? What’s wrong with normal chicken?”

“That’s an excellent pinot from a grateful client, you refugee. Don’t refrigerate it. And chicken’s the most abused animal on earth. It’s all hormones, crappy feed and jumbo creatures with flavourless muscle. You should only be eating the healthy stuff.” He looked severe when she rolled her eyes. “Remember you’ve only got one ovary, cripple.”

“One and a half,” Vee corrected. Aside from their encounter outside the supermarket, she hadn’t seen Joshua in weeks. He wasn’t given to speech-making. It must’ve been a lonely wait in the dark for her to get home; he hadn’t even changed the bum clothes. “How’s the girlfriend?”

“Here we go.”

“What? I’m just asking. I can’t ask questions now?”

“Lyla,” he corrected, “who isn’t my girlfriend, is just fine. You’re just mad because you wish you were in her shoes.”

With a sage nod Vee crunched on vegetables. “Damn right. I do wish I were in her shoes; those were hot shoes. I see you’re still paying top dollar for poor company.”

“Why not? She’s not that bad.”

She returned a sceptical look. His shrewd exterior overlaid a good heart that only a select few were acquainted with. No enemy to feminism, he simply held the view that women were mistresses of their own choices, good or bad. Shallow beauty was a fair exchange for his occasional attentions, in whatever form.

“When are you going to get tired of nasty women, Joshua Allen?”

“Easy enough. Tell me to get rid of her.”

Vee chewed on, mutely.

“See.” He lazily extended a hand across the table but stopped short of touching hers. His skin tone was red-brown and reminded Vee of the soil outside her childhood home. Warm, friendly hands. They’d seen her through a lot, and had been trying to offer more for some time. “Problem is, I never get the nice girls. The best woman I know won’t give me the time of day.”

“I’m not so great any more,” she muttered.

“Wasn’t talking about you, but all right. Hypothetically speaking, say a plain, desperate girl like yourself were to say, ‘My, my, Joshua Allen! I got all this lingerie and massage oil and dirty movies and I just can’t think what to do with it.’ I wouldn’t be averse to –”

Vee burst out laughing and sprayed beer.

She loved their complex relationship. Based on grudging respect and liberal scoops of abuse, over time they’d come to admit to enjoying each other’s company. After the first introduction, they’d maintained a wary distance but soon lost the energy to keep the frostiness going. Just as quickly, Titus resigned his position of wariness and settled for being amused by their sparring.

Now Titus was gone, and they were left nursing a somewhat perverted companionship. Apart from breaking into her place and stocking it with overpriced food, Joshua demonstrated how to theoretically slice chunks off people’s fortunes and re-route it to global tax havens. She showed him how to shoplift and house-break, and posted bail when he got caught. He provided the precise, international units of small, medium and large penis sizes, with an impressive live demonstration. She patronised his women and broke up with the insipid ones by email when he couldn’t be bothered to. At the lowest point of her crushing year he’d given her his apartment, a bank card and lots of time. Sex didn’t factor highly, though occasionally it tried to insinuate itself, with little success.

Taking advantage of the good mood, he asked: “So what’s this article you’re working on?”

She told him, omitting the strange visions and anxiety attacks.

“Sounds like heavy stuff.”

“That’s not the half of it. As dysfunctional goes, this family sounds like textbook material. The strangest part is, Adele Paulsen hates their wealthy guts but won’t go as far as accusing them of wrongdoing, least not as far as murder goes. Her kid goes AWOL, and none of the Fouries appear to give a damn. In her book they’ve moved on with their lives and are ignoring the whole thing like it never happened. You know that big-time healthcare facility that’s been constructed, the Wellness Institute?”

Joshua flashed a smile of mock smugness. Illness was a luxury he couldn’t afford, not on his bonuses.

“Well,” she continued, “some of us are still human enough to get sick once in a while. We can’t all crash-land from Krypton in perfect health and Gucci shirts.”

“This old thing? It’s Mr Price.”

“Mttsshw,” she sucked her teeth amiably. “It’s that fancy new glass and chrome clinic, and they’re adding a physio recovery unit, this mega swimming pool, gym and spa, etcetera. The works. Everybody goes there, or is trying to get in, and it ain’t cheap.”

“Since when are you everybody?” He gave her a look as he speared a carrot strip and bit it in half. “And why in tarnation does a hospital need a pool and spa?”

“Apparently that’s why it’s the ‘institute’ and not just a clinic or hospital. Apparently nobody wants to be confronted so openly with the fact that they’re diseased and mortal, which is what most hospitals are good at. They say,” she stressed, to show she wasn’t taken in despite being a patient herself, “they’re promoting a healthy lifestyle and mindset package, which is all the rage now. Getting away from the old-school practice of just patching people up and cutting them loose.

“Anyway, the Fouries are far from starving, from what I’ve heard. Both parents are on the senior staff of the institute. They offered Adele Paulsen money for her ‘cooperation’ before, when it involved saving their son’s life, but ever since her daughter went missing she’s felt a distinct lack of support on their part.”

She opened the envelope containing the documents on Jacqui’s case: copies of the official police report; statements from all the people questioned; newspaper clippings covering the event; hotline numbers to call for missing children sightings. She slid the second photograph in the pile towards him.

“That’s the basket she put all her eggs in,” she said, tapping the image of a man in the snapshot. “Ashwin Venter, the boyfriend. Six years older, garage mechanic, bit of a bad boy with a record. Obviously Mommy didn’t approve. She told Jacqui to end the relationship; they fought, and Jacqui ended up sneaking around behind her back. When Adele found out her precious was still running around with a guy that much older, and that she’d started having sex with him, well you can imagine how it went down. Typical mother-daughter stuff.

“But she swears, Adele now, that this guy had the perfect motive for murder. She suspects Jacqui was pregnant, from the way she was acting before she went missing, and that Ashwin found out and flipped. She heard them fighting a couple of times but couldn’t really pick out what it was about. One day Jacqui even came home with bruises, and wouldn’t talk about how she got them. She just told her mom that she hoped she was happy now, because she’d broken up with him. He obviously didn’t take it well. Came by their house a few times threatening things and causing a ruckus. They once had to call the neighbours to get him off their property.”

Joshua eyed the photograph sceptically. Venter had a protective arm draped around his girl, the look on his face one of overplayed bravado. He was pale, freckled, moderately well built but not especially so, and not much taller than average. “I guess bad boys come in all flavours,” he muttered. “So he killed her because he found out she was having his baby? Doesn’t sound like your everyday male reaction.”

“My thoughts exactly. But according to Adele this guy’s typical coloured trash – her words, not mine. In his teens he was part of a gang. Then his father died and he inherited the business, which he couldn’t manage, and it started losing money. On top of that he’s got two kids with other women. He’d been hauled into court for child maintenance and was seriously struggling to make ends meet. Basically he wouldn’t have been over the moon about baby number three. He probably saw Jacqui as a soft option. Naive young girl star-struck with a big-time player. The way Adele tells it, he begged her to get rid of the baby, she refused and then it went downhill fast.”

“And she knows this how?”

“She doesn’t know anything for certain. But he confessed that they’d argued and even fought physically before, and they had a huge bust-up on the day she disappeared. The cops had him down as the primary suspect, especially when it turned out he was the last person to see her alive and he didn’t have an alibi other than his sister. They brought him in for questioning a number of times, even held him in custody for two days without a formal charge, but with no evidence they eventually had to let him off the hook. No body, no crime.”

Joshua looked puzzled. “So what, the cops hound one guy without much to go on, then suddenly the case goes cold? They didn’t have a body, but surely they had some evidence to build a case. People disappear all the time, but rarely without a trace. Girl leaves home –”

“Girl leaves home on a Saturday morning, just after ten,” Vee took up the opener, rifling through her memory to recount the report. If there was one thing her brain was good at, it was spooling facts, although the flipside was blanking out when presented with overwhelming amounts of colourful display in malls and supermarket aisles.

“She cleans her room and takes off for tennis practice at Newlands Sports Club with her friends, or so she tells her mom. That part of the story holds up.

“From there the holes start appearing. Just before midday Adele called to find out where she was, got told they were on their way to lunch in Rondebosch. Like most teenagers, Jacqui was good at white lies, so her mother took to checking on her quite a lot, particularly on weekends. Didn’t do much good, because Jacqui could still give her the slip. She ditched her girlfriends and went to Ashwin’s garage in Athlone. According to him, it was just to talk about their relationship, but it blew up into a big argument. He wanted her back, and she wasn’t having it. He swore up and down that the subject of pregnancy never came up. The prospect of having another child, this time with his beloved, wouldn’t have scared him but made him the happiest man alive.

“That’s when the trail goes cold,” Vee threw up her hands. “By around four in the afternoon Ashwin gave up the bended-knee act and Jacqui left. He swore he never laid a hand on her that day. Nobody admitted to seeing her again. Everybody who tried to call her, once they started to get really worried, said her cell was switched off. Wherever she ended up, I’m guessing that phone ended up there with her.”

“Not necessarily,” Joshua countered. “She could’ve lost it, or it could’ve been stolen.”

“True, possible. Anything’s possible at this stage,” Vee murmured absently, trailing off. “Sorry I forgot your birthday,” she added when she spoke again. She bridged the gap by covering his hand with hers. “Meant to send you a male stripper this year.”

“Shucks, guess I missed out.” He squeezed her fingers. “Don’t worry about it. I wasn’t here anyway. New York.”

“I’ll make it up to you.” Finally, she taxied onto the runway she’d been circling over since they ran into one another, turning on him eyes that were clear and untroubled, with the question: “So how’s your friend doing?”

There was always a tightening of his jaw when she laid her hopes on the table. Much as she loathed to admit it, her ex-fiancé still had a hold over her.

“Haven’t heard from him,” he replied, holding her gaze steady. “You know I wouldn’t hide it from you if I had. He hasn’t been much of a friend lately, has he?”

Vee nodded, looking away. She sometimes forgot, when the anger and selfishness overwhelmed her, that she wasn’t the only person Titus had abandoned. Joshua had never openly threatened or railed against him, but she’d seen the hardening jaw and diamond glint of anger in his eyes and known. There was a Code Among Men, and only God knew how many of its rules Titus had broken.

The notion that her ex was a treacherous disappointment had to remain uppermost in mind if she intended getting her priorities back in order. She couldn’t speculate on the when, but if a fully operational, centred state mattered, then a complete emotional exorcism was needed. Admittedly, for the past few months, excepting a sprinkle of bad days, Titus hadn’t crossed her mind as often and the anxiety symptoms seemed to be fading with his memory.

For a brief moment she considered telling Joshua about the attacks, and then thought better of it. He had given more than enough, in ways she could never repay, not that he’d ever accept anything of the sort. All he’d ever asked was that she be honest with herself and aware that putting on a brave front would end up causing more harm than good. The frightening magnitude of her symptoms indicated there was something concrete in his theory. Reconsidering reticence, she turned towards him.

Just then, Joshua said: “It’s strange, but there’s something –” He stopped, realising she’d been about speak. “What? You looked like you were about to say something.”

“Uh, no. Just a random thought.” She waved it away. “What’s strange?”

He regarded her for a long moment before continuing. “The story sounds familiar. I dunno, something you said in the beginning . . .”

“Well, you were in Cape Town two years ago. Jacqueline Paulsen’s disappearance didn’t make headlines, but it did get some media coverage. Maybe you read about it or heard some talk.”

“No, that’s not it. More recent . . . Anyway, it’s gone now. But it’ll come back to me.”

When he stood up, she felt an involuntary pang. He rarely left willingly, not before she threw him out in good spirit. Monro barked in shared disappointment as he ambled back and forth between them, loyalties torn. Eventually he settled on his haunches beside Vee, realising which side his bread was buttered on.

“When’re you planning to come get your dog?” she asked as they walked to the door.

“Next week,” Joshua lied promptly. “Saturday. Next week Saturday, bright and early.”

Vee chuckled, shaking her head. “Next week” was nearly a year-old excuse. A vicious attack during childhood had left her terrified of dogs until the gorgeous husky came along. Ignoring all her misgivings in his usual flippant way, Joshua had left the puppy behind for a few days, promising to return when he had a bigger place to comfortably keep an animal. He was still kicking back in the comfort of a lavish Sea Point apartment while Monro enjoyed summer afternoons tearing up the little front lawn.

“Your eyes look like a horror movie. Get some rest,” he ordered gently. “And don’t stay up all night chasing clues down that black hole between your ears. It’s late.”

He paused with her in the doorway, dawdling as if to add a parting thought. Close enough for her to take in his warmth and distinctly heady male scent, Vee expected it when instead of speaking he leaned in and planted a kiss near her mouth. She didn’t expect it when he pulled away with a sigh before kissing her again, full on. The brush of his lips was soft and incredibly warm, and she was taken aback by the heat that surged through her frame. She lingered for a moment before she pulled away, suppressing a visible shudder.

Joshua cleared his throat sheepishly. “And, um, eat something,” he added, walking away backwards. “Fatten up a bit. Your butt isn’t what it used to be.”

Vee latched the door and bit into a smile. Behind her, Monro gave two sharp barks and prodded her legs.

“Don’t you dare judge me,” she muttered as she trudged upstairs.