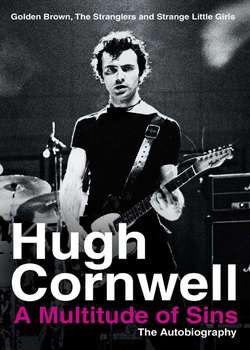

Читать книгу A Multitude of Sins: Golden Brown, The Stranglers and Strange Little Girls - Hugh Cornwell - Страница 7

BACK TO THE HOTEL ROOM

ОглавлениеIt’s getting to the time to prepare for the gig and I’m not feeling any different. I am convinced that I’ve finally seen the light at the end of the tunnel and I just want to get on with it. I go through all the little rituals I do to prepare for a gig: I have a cat nap for about ten minutes, I have a shit and a shave, I check that my shoelaces are tight but not too tight, and I wait for the call down to the hotel lobby.

As usual, no one says much during the ride to the venue. John Ellis, ex-Vibrators, is with us on this tour as a second guitarist and he is the most talkative. I promise myself that I will put everything into this concert as it’s going to be my last one as a Strangler. Normally a live set goes quicker than you would expect, but this one just races by. Before I know it, we are on stage doing an encore or two and then it’s all over and we are backstage in a caravan winding down. Someone asks me something about next week and I mutter an incoherent answer over my shoulder as I change my clothes. It’s been a good performance and the last thing I want to do is bring everyone down by announcing my news to the rest of the group. I make some excuses and manage to get away as soon as I can. I pass John Ellis on the way out the door, and I say, ‘Have a nice life’ to him, probably because he’s an outsider and has nothing to do with my decision. I grab one of the courtesy cars at our disposal and get a ride into Soho, where I get paralytically drunk with some unsuspecting friends …

Anyone who has been in a professional band for any length of time can tell you that it resembles being in a marriage without the sex. Long periods of time are spent in one another’s company; there are many shared experiences, in sickness and in health, for richer for poorer, etc, etc. It does help if you share a similar sense of humour or have similar tastes, but most of all, you have to enjoy each other’s company. Apparently, Sam & Dave, the immortal soul singers, only meet when they take to the stage together, and when the show is over they exit from different sides of the theatre.

Maybe I wouldn’t have left the group if I’d been having sex with one of them. To be really safe, maybe I should have been shagging them all. The only trouble is, gee whiz, I’m not that way inclined. As Sam Kinnison, the American stand-up comedian used to say, ‘I can’t stand the hairy backs.’

So I guess you can reach the conclusion that I wasn’t enjoying the company of Messrs Black, Burnel and Greenfield any more. When we first got together, we were finding out so much about each other. There was always something to ponder over and be curious about. I suppose we had got to know each other so well by 1990 that there was nothing left to find out, or nothing left that I was interested in. To spend sixteen years with one person is quite an achievement. I’d spent it with all three of them.

We had been working continuously together for all those years by the time I left and I remember one moment when the passage of time became a realization. We had returned to The 100 Club in Oxford Street, London, to play a secret gig prior to a tour, having last played there some seven or eight years previously. I found myself there in the afternoon while Jet was setting his drums up. I heard him laughing to himself. He was sitting on his drum stool and had recalled the last gig we’d played there all those years before. He’d remembered taking his watch off and finding a space in a brick wall beside him in which to put it. He had then forgotten about it until that moment and had checked the spot. Not only was the watch still there, but it was still keeping time. Passage of time is barely perceptible unless you can see that something has changed. The trouble is that The 100 Club still looks more or less the same as it did in the Sixties.

By contrast, I was a regular at another Soho club just round the corner, The Marquee, which no longer exists. It was there that I saw The Who, The Yardbirds (with Beck, Page and Clapton all playing together in the same line-up on one occasion), The Spencer Davis Group, and my favourites, The Graham Bond Organisation, with Graham Bond on organ, mellotron and soprano sax, Dick Heckstall-Smith on sax, Jack Bruce on bass and Ginger Baker on drums (they had tried out John McGoughlin on guitar but had sacked him). Then there was The Mark Leeman Five and The Action.

I was still at school and I’d go there by myself maybe twice a week. After the gig I’d get the Tube home and be back before midnight. One night a dodgy man in a raincoat offered me some purple hearts as I walked back to the Tube station. The Marquee was a very, very cool place, and hardly anyone spoke to one another, or barely moved. They just stood still and listened to the bands. It was perfectly portrayed by Michelangelo Antonioni in his film, Blow Up, in which The Yardbirds are playing and Jeff Beck destroys his guitar and throws it into the crowd as an offering. Going back there with The Stranglers it seemed a lot smaller, but it was a thrill for me. We played there once in the early days for a fiver supporting Ducks Deluxe, who shared the same management as us. After the gig we packed our equipment back into the ice-cream van and I went to collect the fiver from Sean Tyla of Ducks Deluxe, as instructed by Dai Davies, one of the managers. Sean fobbed me off a couple of times, saying he hadn’t been paid yet and I’d have to wait. I finally got it out of him about two hours later, and had great pleasure seeing him six months later when his new band The Tyla Gang were supporting us at Oxford Polytechnic.

But to get back to the point, it just wasn’t happening for me in The Stranglers anymore. The last thing I wanted to do was to go through the motions and become an anachronism. The whole band had grown apart. When, we started out, we were each other’s family. One by one, the band members started their own families and we stopped relaxing together. We’d meet up, rehearse, disperse, reconvene at a studio, record, disperse again, and the same thing would happen when a tour was scheduled. I had no idea what any of the other three were up to outside of when we worked together. It really had become a day job and you know what they say about that. But I did give it up and I feel much better for it. I just couldn’t see myself being in a group at the age of fifty, but I could see a future making music.

I was also getting tired of compromising. In a group, there is a certain amount of democracy or it won’t function. A group’s collective psyche or image is a mixture of all the things that everyone brings in, and the less you bring in, the less of you is found in the collective psyche. The Stranglers’ coat didn’t fit me anymore. I didn’t feel like one any longer and the more I thought about it, the less comfortable I felt, and the less satisfied I became. I was writing more and more by myself, creating even more of a distance from the others. While we were working on the last studio album I was on, called 10, I was accused of trying to turn it into a solo album, because I was layering harmonies on top of my own voice on a song I’d written, which the others had approved for the album.

A big paradox of the punk movement occurred to me recently. Most of all the significant bands of that period are alive and well and still performing more or less the way they were back then. This seems funny, considering it was a nihilistic movement and yet there was only one star casualty, namely Sid Vicious. But the reason is simple enough. The bands are still there because it pays the rent. There’s nothing wrong with that, it’s the ethic behind why most people all over the world do their jobs every day. But I did take a huge financial risk when I left The Stranglers. We were due to sign a new publishing deal soon afterwards that would have brought in a fat cheque for us to share, but I knew to stick around just for that didn’t make any sense. Any decent lawyer would have smelt a rat if I’d left after signing, and we’d have been sued. The funny thing is, we’d very nearly split up years before when Dai Davies and Derek Savage, our first managers, suggested we should call it a day after the first three albums, which we’d released in the unbelievably short period of just fourteen months.

After I left, our accountants clarified that our greatest money-making period had been in those first frenetic years. Our first three albums had cost very little to make, and our tastes were sufficiently crude then that we didn’t expect the luxuries one can get accustomed to. We were so delighted to be successful that we failed to realize we weren’t actually taking home much money. Our managers knew that as long as we had everything we needed, we would be content enough to carry on regardless. On several occasions, a planned tour of Europe would come in costing more than it generated in concert fees, so our managers would go to the record company asking them to pay the difference. This they would do, but charge it against our royalties. The managers would leave with the cheque for the shortfall, and then promptly take their commission off, leaving the tour still in the red, and them in the black. We would go and do the tour, staying in five-star hotels, not realizing that we were paying all the costs. This all helps to paint the picture of a golden goose laying eggs which everybody gets a nice piece of … except the goose. I think it’s pretty accurate. I somehow feel that this part of my story is probably the same as that of a lot of musicians, but I’m not complaining. After all, I got to perform on stage, I got to shag the birds, and I got to take the drugs and drink the booze. And I got my picture in the paper!

The unsung heroine of the punk era is Shirley Bassey. If she hadn’t been selling truckloads of records in the mid-Seventies, United Artists Records wouldn’t have been able to sign The Stranglers, Buzzcocks, Dr Feelgood, 999, Wire and many others. She was the ‘cash cow’ of punk and has never realized it. She also provided us with our first record producer, Martin Rushent, who was the straightest person any of us knew apart from our parents. He’d been producing Shirl’s records for a while and was assigned by the record label essentially to record what we did in live performance. Originally it was thought that we’d release a live album, but as soon as we got into TW Studios in Fulham, with Martin and Alan Winstanley (the house engineer), we were able to improve on our live performance. We’d already recorded demos at TW Studios before being signed to the label, so we had suggested to United Artists that we go there again.

Martin couldn’t believe his luck. He’d been brought in to produce this punk band that he had no experience of, and here was an engineer who had worked with the band before, working in his own studio. Subsequently the recordings went down very quickly and our first album was soon finished, plus four or five extra tracks that we put on our second album. I was fascinated by the whole process of recording. Anything was possible if you had the time. Martin helped us to relax in the studio environment. He had a huge repertoire of jokes, as I did, and would be on the phone to his accountant a lot of the time buying and selling shares. He had his fair share of production ideas too and went on to ground-breaking work with The Human League on their album Dare a few years later.

We’d grown out of Martin’s influence by the time that our third album, Black And White had been delivered, but we did continue to work with Alan Winstanley, who was by then making a fine reputation for himself as a producer in his own right. Alan later teamed up with Clive Langer, from the band Deaf School, and together they produced all of Madness’s hits, and later worked with Morrissey. Their relationship is a similar one to that between Martin Rushent and Alan. Clive Langer is an extremely funny man but is more of a philosopher than Martin ever was. I worked with Clive and Alan on my second solo album, Wolf, whilst I was still in The Stranglers and had great fun working with them. Clive would be discussing his take on life with me at the back of the room while Alan would be working at the desk trying to get some sense out of him. One night Clive spilt a drink over the mixing desk when we were getting drunk in the studio and instead of panicking the three of us collapsed in hysterics.

Such chemistry between people is the secret ingredient in successful working partnerships and that’s why Clive and Alan still work together. There was also that chemistry between John Burnel, the bass player in The Stranglers, and myself for much of the time I was in the band. He would constantly be coming up with great bass riffs for me to write lyrics to and mould into songs, and I had chord progressions that he could put a lyric to. Unfortunately he wasn’t as inspired to work on my musical ideas as I was on his. Add to that the fact that I had more confidence in my voice than he had in his, and you end up with frustration on my part. Gradually, I was turning more and more of my musical ideas into songs by myself, and it was getting easier all the time. John would disappear to France every summer to see his parents and I would be left to finish my songs alone. When we finished our eighth studio album, Aural Sculpture, I had written half of the songs on it. Laurie Latham was with us in Brussels, producing the record on the suggestion of Muff Winwood, our man at CBS Records. Laurie had delivered Paul Young’s first album for CBS which had been a massive seller. Most people aren’t aware that he produced the classic New Boots And Panties!!! by Ian Dury more or less single-handedly, plus most of Ian’s later work. Laurie and I hit it off immediately. He had a great sense of humour, which was quite dry and similar to mine. Laurie’s great forte is his engineering skill in the studio, which means that he can produce without having to explain his ideas to someone else. This saves time and can be crucial to seeing an idea come to fruition quickly. Laurie has since produced two solo albums for me, HiFi and Guilty, doing a brilliant job on both of them. I can honestly say I’ve never laughed so much making a record as I have done with Laurie. He’s a true recording genius.

We were due to work with Laurie again on the next Stranglers’ album, Dreamtime. Laurie had stayed on in Brussels with his family after we’d finished Aural Sculpture, and we were due to repeat the process there with him. But when he heard the songs we had available, he told us he thought we were unprepared and that the sessions should be postponed. He was absolutely right, of course. John and I had had a fallout in Italy (more later) and our writing partnership had suffered. From then on it became a struggle to hold it together. We decamped from Brussels and did some more writing. We never did get back together with Laurie, and it would be nearly twelve years later that I next worked with him.

I’m sure people don’t realize the number of variables involved in making a record. I frequently envy painters the immediacy of their connection to their work. It’s a thought process going from a brain to a hand, then straight on to canvas. It’s simple, precise, and organic. A songwriter writes a song on a guitar. So far, so good. But then it must be recorded. Should it be recorded acoustically with just a guitar and voice, or with something else? What instruments should be used? Who should play these instruments? Where should it be recorded? Who should produce it? Who should engineer it? Should the song be rearranged? Would it sound better in a different key? How many times should the musicians try to record it? Which version is the best one? Once it’s recorded, who is going to mix the levels of the instruments? Which mix sounds the best? Finally, is anybody going to hear it? WHO CARES? It’s such an achievement to make a record that you feel totally drained by the end. And it ceases to be a part of you anymore, the umbilical cord is cut once the recording is finished.

John’s response to the awkward situation between us was to write more by himself. Consequently, there were far fewer co-written songs on the last two albums, Dreamtime and 10. These albums were made almost entirely with each member of the group contributing alone with the producer and engineer in the studio. Previously, Jet was the only group member who had been keen to be around the sessions for the whole time. Yet, even he started to be absent whilst 10 was being made.

I left the band for a myriad of different reasons. Since then I’ve noticed a change in my attitude to life. I now try to be more philosophical about things. And a weight does seem to have been lifted from my shoulders. There were too many rules and regulations associated with being a Strangler, and who needs any more of those in life? I’ve played with a lot more musicians since I left and my guitar playing has improved. I’m convinced that The Stranglers with me involved was past its sell-by date. I still believe that. Playing is fun again and I’m enjoying playing the old songs. Being in a band can be great fun but it’s also rather like the army. I started to feel that my contribution was not being appreciated by the others, and that it was being resented – and if I ever feel like that, it’s time to move on. Life is too short to waste time with people who don’t value you and there are an awful lot of people out there. I look back on my Stranglers days as an apprenticeship. I learnt a lot about stage skills, songwriting and the music business in general. But bands are not an ideal forum for a personality to express itself, because the collective personality always comes first.

I can think of several moments in my last years in the group that were pivotal in persuading me to take the final decision to leave. The first was following the success of ‘Golden Brown’, which in itself was a surprise to us all, coming as it did after a long period of low-charting single releases. We were on tour in France when Hugh Stanley Clarke from EMI came out to meet with us to discuss what should be the follow-up single. It’s imperative to build on any success in the charts and we all agreed with the record company that a second Top Ten single would bring us right back into the public eye. We met with Stanley Clarke before a gig and he revealed that EMI were keen to release the song ‘Tramp’ as the next single. I was quietly very happy with this, as it was a song I had written alone and presented to the band. I knew that Jet liked ‘Tramp’ but he wasn’t saying much. John immediately rejected the idea, saying that the song was too commercial. Within half an hour, he had convinced everyone in the room except me that ‘La Folie’ was the ideal follow-up single. This was a song we had written together. He had sung it in French, having written the lyrics to a musical piece of mine. It was a reference to the madness of love and was the title track of the current album. It was a beautiful song and could possibly have succeeded if sung in English, but in French it was a non-starter. Its subsequent failure to chart high enough (Number 47) put us back a long way. Later on, we did manage to retrieve the situation somewhat. I got everyone to agree to re-record the song ‘Strange Little Girl’ as the next single. It had been one of our original demos when we were looking for a record deal in 1975 and EMI had turned it down. Tony Visconti produced the whole thing for us and did a great job. ‘Strange Little Girl’ charted at Number 7 on release.

Two further incidents showed me that the others weren’t appreciating my efforts. One happened in Brussels when we were recording the album Feline. Jet and I had stayed very late at the studio one night with our engineer Steve Churchyard to finish a mix of my song ‘Souls’, and we were very pleased with what we’d done. We came to the studio the next day to find the quarter-inch tape of the mix pulled off its reel, stuffed into a large envelope and taped to the studio door with ‘THIS IS SHIT’ written on it. I got as far as packing my bags at the hotel and booking a flight home before I got a call of apology from John on behalf of Dave and himself.

The second incident concerned the making of the video for ‘Always The Sun.’ I had storyboarded the video and everybody approved the idea. We shot the video then the director and I spent a good fifty hours in an editing suite finishing it off. Upon seeing the result, the others said they hated it but didn’t explain why they had approved the idea and the storyboard earlier and also participated in the shoot for it.

I mentioned earlier that John and I had fallen out in Italy. We were backstage after a gig and were swapping our impressions of the performance as we usually did. This particular set had begun with ‘Something Better Change’, an early number which John sang. After the guitar intro, John and I were jumping in the air and landing to coincide with the other instruments starting the song. It was a very dynamic beginning to the set, but we weren’t synchronizing the jump that night, and when I mentioned to John that he hadn’t been on time, he attacked me. He’s had many years of karate training and can quite easily incorporate this into a violent disagreement. He had to be restrained by several people to avoid injuring me. Later on that night, he apologized profusely but I made it clear to him that I was going to have to be very careful what I said to him in future, for fear of my own safety. It was at this point that I resolved to secure some sort of solo recording arrangement, as it was becoming clear that I couldn’t be sure how long our relationship within the band was going to last.

We wrote and recorded demos for the album 10 at John’s house in Cambridge using a small recording set-up in a barn. I would travel up there from the West Country to work for a few days. It made good sense to take a break and catch up with my own personal life and I was intending to leave when John accused me of not being totally committed to the sessions. ‘I’m going to stay here until we’ve finished everything we need to,’ he stated.

It occurred to me that it was very easy for him to continue his private life when he was working in his own backyard but, considering his outburst in Italy, I didn’t want to take any risks by discussing it with him. I did not want to provoke him and just made it clear that I had to take a break, so I left.

So where does that leave us? Rehearsing for a tour to promote 10, and looking forward to touring America, which was the market the record had been produced for. CBS had brought in Roy Thomas Baker, a larger-than-life individual, veteran of numerous Queen albums and teller of many stories about working with rock legends. CBS thought that he could groom our sound for the States, which was a market we had never exploited. Our status there was that of a cult band. We hadn’t been to the US very often, and ‘Golden Brown’ had never had a release there, the general consensus being that it fell between two stools. The Stranglers’ name meant one market, but the song itself meant another, and the marketing gurus over there couldn’t find a way to reconcile the two. The concise streaming of music on American radio left ‘Golden Brown’ out on a limb and unplayable.

Our managers and I had gone over to New York to do some advance promotion for the album. When my part in that was done, I left them there to wheel and deal whilst I returned to London to rehearse with the other three for the UK tour. Our managers then arrived back and immediately came to see us at the rehearsal studios. We were expecting news of US release dates and a touring schedule but instead they told us there were to be no American singles and, more surprisingly, no US tour. They had been unable to interest an American agent to book a tour over there. This was the point at which the thought of leaving the band became a possibility to me. I had been delaying the decision, hoping that touring America might give the group a new energy and maybe some success there. Suddenly there was a huge gap in our work diary.

So, as I have mentioned, we finished the tour with that gig at Alexandra Palace and I walked out. I didn’t even have any faith that the rest of the band would be disappointed. I didn’t want to discuss it amidst all the acrimony and recrimination. I had no idea if they were intending to carry on or not without me. David Buckley, who wrote The Stranglers’ aforementioned biography, No Mercy, told me he was very surprised that none of the band tried to persuade me to reconsider leaving and perhaps take a sabbatical instead. I guess he had a point.

As far as answering that second question – about rejoining the group – it’s as far from my mind as anything could be. Maybe if they had split up when I left, there could be some dynamic excitement about getting back together again after such a long time. But you can’t re-form a band that hasn’t split up. Good old Ian Grant, one-time manager of The Stranglers and my first manager as a solo artist, said he could get me a million quid if I got back together with them, but I don’t need a million quid. I’ve put a lot of work into where I am today, and I have no intention of nullifying all that effort by such a dumb move.

The day after the gig at Alexandra Palace, I telephoned the others to tell them what I had decided. I said I didn’t want to be a Strangler any more. Their reactions were:

JOHN: very sympathetic, said he felt I hadn’t been happy for a while. He was quite emotional.

JET: he said, ‘OK. Fine,’ was completely nonplussed and didn’t comment, which surprised me.

DAVE: he asked me, ‘Will we be having a meeting?’

We did all meet up together once more in our accountants’ offices about two months later to divide the spoils. I said that I’d like to get my amplifiers and guitars back. John said, ‘You’ve been collecting guitars for years. You shouldn’t get them all back.’

I thought of something.

‘If you hadn’t smashed so many basses on stage, you’d probably have had as many yourself.’

Jet tried to keep a straight face but collapsed into his chair with laughter.

I finally got my equipment back a year later.