Читать книгу The Boy Most Likely To - Huntley Fitzpatrick - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter Two

“You’re really doing this?”

I’m shoving the last of my clothes into a cardboard box when my ma comes in, without knocking, because she never does. Risky as hell when you have a horny seventeen-year-old son. She hovers in the doorway, wearing a pink shirt and this denim skirt with – what are those? Crabs? – sewn all over it.

“Just following orders, Ma.” I cram flip-flops into the stuffed box, push down on them hard. “Pop’s wish is my command.”

She takes a step back like I’ve slapped her. I guess it’s my tone. I’ve been sober nearly two months, but I have yet to go cold turkey on assholicism. Ha.

“You had so much I never had, Timothy . . .”

Away we go.

“. . . private school, swimming lessons, tennis camp . . .”

Yep, I’m an alcoholic high school dropout, but check out my backhand!

She shakes out the wrinkles in a blue blazer, one quick motion, flapping it into the air with an abrasive crack. “What are you going to do – keep working at that hardware store? Going to those meetings?”

She says “hardware store” like “strip club” and “going to those meetings” like “making those sex tapes.”

“It’s a good job. And I need those meetings.”

Ma’s hands start smoothing my stack of folded clothes. Blue veins stand out on her freckled, pale arms. “I don’t see what strangers can do for you that your own family can’t.”

I open my mouth to say: “I know you don’t. That’s why I need the strangers.” Or: “Uncle Sean sure could have used those strangers.” But we don’t talk about that, or him.

I shove a pair of possibly too-small loafers in the box and go over to give her a hug.

She pats my back, quick and sharp, and pulls away.

“Cheer up, Ma. Nan’ll definitely get into Columbia. Only one of your children is a fuck-up.”

“Language, Tim.”

“Sorry. My bad. Cock-up.”

“That,” she says, “is even worse.”

Okeydokey. Whatever.

My bedroom door flies open – again no knock.

“Some girl who sounds like she has laryngitis is on the phone for you, Tim,” Nan says, eyeing my packing job. “God, everything’s going to be all wrinkly.”

“I don’t care –” But she’s already dumped the cardboard box onto my bed.

“Where’s your suitcase?” She starts dividing stuff into piles. “The blue plaid one with your monogram?”

“No clue.”

“I’ll check the basement,” Ma says, looking relieved to have a reason to head for the door. “This girl, Timothy? Should I bring you the phone?”

I can’t think of any girl I have a thing to say to. Except Alice Garrett. Who definitely would not be calling me.

“Tell her I’m not home.”

Permanently.

Nan’s folding things rapidly, piling up my shirts in order of style. I reach out to still her hands. “Forget it. Not important.”

She looks up. Shit, she’s crying.

We Masons cry easily. Curse of the Irish (one of ’em). I loop one elbow around her neck, thump her on the back a little too hard. She starts coughing, chokes, gives a weak laugh.

“You can come visit me, Nano. Any time you need to . . . escape . . . or whatever.”

“Please. It won’t be the same,” Nan says, then blows her nose on the hem of my shirt.

It won’t. No more staying up till nearly dawn, watching old Steve McQueen movies because I think he’s badass and Nan thinks he’s hot. No Twizzlers and Twix and shit appearing in my room like magic because Nan knows massive sugar infusions are the only sure cure for drug addiction.

“Lucky for you. No more covering my lame ass when I stay out all night, no more getting creative with excuses when I don’t show for something, no more me bumming money off you constantly.”

Now she’s wiping her eyes with my shirt. I haul it off, hand it to her. “Something to remember me by.”

She actually folds that, then stares at the neat little square, all sad-faced. “Sometimes it’s like I’m missing everyone I ever met. I actually even miss Daniel. I miss Samantha.”

“Daniel was a pompous prickface and a crap boyfriend. Samantha, your actual best friend, is ten blocks and ten minutes away – shorter if you text her.”

She blows that off, hunkers down, pulling knobbly knees to her chest and lowering her forehead so her hair sweeps forward to cover her blotchy face. Nan and I are both ginger, but she got all the freckles, everywhere, while mine are only across my nose. She looks up at me with that face she does, all pathetic and quivery. I hate that face. It always wins.

“You’ll be fine, Nan.” I tap my temple. “You’re just as smart as me. Much less messed up. At least as far as most people know.”

Nan twitches back. We lock eyes. The elephant in the room lies bleeding out on the floor between us. Then she looks away, gets busy picking up another T-shirt to fold expertly, like the only thing that matters in the world is for the sleeves to align.

“Not really,” she says in a subdued voice. Not taking the bait there either, I guess.

I grope around the quilt on my bed, locate my cigs, light one, and take a deep drag. I know it’s all kinds of bad for me, but God, how does anyone get through the day without smoking? Setting the smoldering butt down in the ashtray, I tap her on the back again, gently this time.

“Hey now. Don’t stress. You know Pop. He wants to add it up and get a positive bottom line. Job. High school diploma. College-bound. Check, check, check. It only has to look good. I can pull that off.”

Don’t know if this is cheering my sister up, but as I talk, the squirming fireball in my stomach cools and settles. Fake it. That I can do.

Mom pops her head into the room. “That Garrett boy’s here. Heavens, put on a shirt, Tim.” She digs in a bureau drawer and thrusts a Camp Wyoda T-shirt I thought I’d ditched years ago at me. Nan leaps up, knuckling away her tears, pulling at her own shirt, wiping her palms on her shorts. She has a zillion twitchy habits – biting her nails, twisting her hair, tapping her pencils. I could always get by on a fake ID, a calm face, and a smile. My sister could look guilty saying her prayers. Feet on the stairs, staccato knock on the door – the one person who knocks! – and Jase comes in, swipes back his damp hair with the heel of one hand.

“Shit, man. We haven’t even started loading and you’re already sweating?”

“Ran here,” he says, hands planted hard his on kneecaps. He glances up. “Hey, Nan.”

Nan, who has turned her back, gives a quick, jerky nod. When she twists around to tumble more neatly balled socks into my cardboard box, her eyes stray to Jase, up, slowly down. He’s the guy girls always look at twice.

“You ran here? It’s like five miles from your house! Are you nuts?”

“Three, and nah.” Jase braces his forearm against the wall, bending his leg, holding his ankle, stretching out. “Seriously out of shape after sitting around the store all summer. Even after three weeks of training camp, I’m nowhere near up to speed.”

“You don’t seem out of shape,” Nan says, then shakes her head so her hair slips forward over her face. “Don’t leave without telling me, Tim.” She scoots out the door.

“You set?” Jase looks around the room, oblivious to my sister’s hormone spike.

“Uh . . . I guess.” I look around too, frickin’ blank. All I can think to take is my clamshell ashtray. “The clothes, anyway. I suck at packing.”

“Toothbrush?” Jase suggests mildly. “Razor. Books, maybe? Sports stuff.”

“My lacrosse stick from Ellery Prep? Don’t think I’ll need it.” I tap out another cigarette.

“Bike? Skateboard? Swim gear?” Jase glances over at me, smile flashing in the flare of my lighter.

Mom barges back in so fast, the door knocks against the wall. An umbrella and a huge yellow slicker are draped over one arm, an iron in one hand. “You’ll want these. Should I pack you blankets? What happened to that nice boy you were going to move in with, anyway?”

“Didn’t work out.” As in: that nice boy, my AA buddy Connell, relapsed on both booze and crack, called me all slurry and screwed up, full of blurry suck-ass excuses, so he’s obviously out. The garage apartment is my best option.

“Is there even any heat in that ratty place?”

“Jesus God, Ma. You haven’t even seen the frickin’ –”

“It’s pretty reliable,” Jase says, not even wincing. “It was my brother’s, and Joel likes his comforts.”

“All right. I’ll . . . leave you two boys to – carry on.” She pauses, runs her hand through her hair, showing half an inch of gray roots beneath the red. “Don’t forget to take the stenciled paper Aunt Nancy sent in case you need to write thank-you notes.”

“Wouldn’t dream of it, Ma. Uh, forgetting, I mean.”

Jase bows his head, smiling, then shoulders the cardboard box.

“What about pillows?” she says. “You can tuck those right under the other arm, can’t you, a big strapping boy like you?”

Christ.

He obediently raises an elbow and she rams two pillows into his armpit.

“I’ll throw all this in the Jetta. Take your time, Tim.”

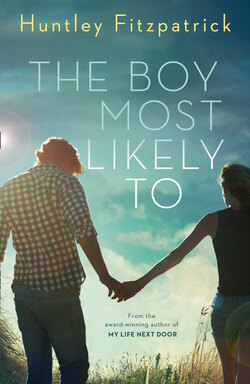

I scan the room one last time. Tacked to the corkboard over my desk is a sheet of paper with the words THE BOY MOST LIKELY TO scrawled in red marker at the top. One of the few days last fall I remember clearly – hanging with a bunch of my (loser) friends at Ellery out by the boathouse where they stowed the kayaks (and the stoners). We came up with our antidote to those stupid yearbook lists: Most likely to be a millionaire by twenty-five. Most likely to star in her own reality show. Most likely to get an NFL contract. Don’t know why I kept the thing.

I pop the list off the wall, fold it carefully, jam it into my back pocket.

Nan emerges as soon as Jase, who’s been waiting for me in the foyer, opens the creaky front door to head out.

“Tim,” she whispers, cool hand wrapping around my forearm. “Don’t vanish.” As if when I leave our house I’ll evaporate like fog rising off the river.

Maybe I will.

By the time we pull into the Garretts’ driveway, I’ve burned through three cigarettes, hitting up the car lighter for the next before I’ve chucked the last. If I could have smoked all of them at once, I would’ve.

“You should kick those,” Jase says, looking out the window, not pinning me with some accusatory face.

I make to hurl the final butt, then stop myself.

Yeah, toss it next to little Patsy’s Cozy Coupe and four-year-old George’s midget baby blue bike with training wheels. Plus, George thinks I’ve quit.

“Can’t,” I tell him. “Tried. Besides, I’ve already given up drinking, drugs, and sex. Gotta have a few vices or I’d be too perfect.”

Jase snorts. “Sex? Don’t think you have to give that up.” He opens the passenger-side door, starts to slide out.

“The way I did it, I do. Gotta stop messing with any chick with a pulse.”

Now Jase looks uncomfortable. “That was an addiction too?” he asks, half in, half out the door, nudging the pile of old newspapers on the passenger side with the toe of one Converse.

“Not in the sense that I, like, had to have it, or whatever. It was just . . another way to blow stuff off. Numb out.”

He nods like he gets it, but I’m pretty sure he doesn’t. Gotta explain. “I’d get wasted at parties. Hook up with girls I didn’t like or even know. It was never all that great.”

“Guess not” – he slides out completely – “if you’re with someone you don’t even like or know. Might be different if you were sober and actually cared.”

“Yeah, well.” I light up one last cigarette. “Don’t hold your breath.”