Читать книгу The Cape Wrath Trail - Iain Harper - Страница 10

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

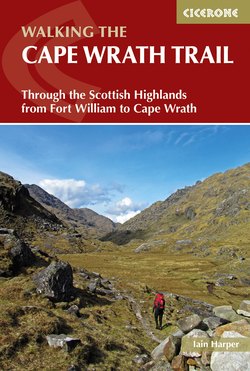

View back to Glenfinnan

The Cape Wrath Trail is part of a vast network of 720 long-distance paths that criss cross the British Isles. Some of these are official National Trails – well maintained long-distance footpaths and bridleways administered by Natural England and the Countryside Council for Wales and waymarked with acorn symbols. In Scotland, the equivalent trails are called Long Distance Routes and are administered by Scottish Natural Heritage. There are currrently 15 such routes in England and Wales and four in Scotland. Many other long-distance paths are equally well maintained and waymarked. The Cape Wrath Trail is fairly unique, combining a complete lack of waymarking and a variety of routes rather than a firmly fixed trail. The route often follows traditional drovers’ and funeral routes, dating back hundreds of years, that provided the only means for crofters to move themselves and their animals around the rugged landscape of the Scottish Highlands.

The route as we currently know it has evolved more recently, with landscape photographer David Paterson’s 1996 book The Cape Wrath Trail: A 200 mile walk through the North-West Scottish Highlands setting out a basic template. Paterson set off from Fort William with his camera and a bivvy bag and his route was initially along the Great Glen Way, hence its inclusion in this book as a route alternative. The route starting along the Great Glen Way was further popularised by Cameron McNeish, wilderness backpacker and editor at large of The Great Outdoors magazine, who suggested a more practical and less circuitous alternative to Paterson. McNeish has included this version of the route in his Scottish National Trail, which spans the entire country. He neatly summarises the trail: ‘It’s the sort of long-distance route that most keen walkers dream of. A long tough trek through some of the most majestic, remote and stunningly beautiful landscape you could dare imagine. The Cape Wrath Trail is a challenging and often remote route which, in essence, could be described as the hardest long-distance backpacking route in the UK.’ A later book, North to the Cape by Denis Brook and Phil Hinchcliffe, cemented the trail’s burgeoning popularity, and first suggested starting the trail through Knoydart rather than the Great Glen, a route that has now become firmly established as the more popular choice with walkers.

Climbing towards the Forcan Ridge (Stage 4)

Because of its difficulty and the relative lack of amenities, the Cape Wrath Trail has resolutely defied the commercialisation that has come to other long-distance backpacking trails in the Highlands like the West Highland Way.

More recently, the trail has become part of the International Appalachian Trail (IAT), a backpacking trail running from the northern end of the Appalachian Trail in Maine, USA through New Brunswick, to the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec, Canada after which it extends to Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador. Geological evidence shows that the Appalachian Mountains and the mountains of Western Europe and North Africa are parts of the former Central Pangean Mountains, made when minor supercontinents collided to form the supercontinent Pangaea more than 250 million years ago. With the break-up of Pangaea, sections of the former range remained with the continents as they drifted to their present locations. Inspired by this evidence, efforts are being made to further extend the IAT into Western Europe and North Africa.

Geology and wildlife

Descending to Loch an Nid (Stage 7)

This book is a walking guide not a natural history guide, but suffice to say that if you’re a fan of rocks and creatures, you’re in for a real treat. Assynt in particular has been described as an ‘internationally acclaimed geological showpiece’ and you’re as likely to bump into a geologist as a stag wandering through its glens. You’ll also be spoilt for choice with fauna, from the golden eagles of Knoydart, ptarmigan, red deer, a vast array of birds and even the odd seal in the western sea lochs. One of the best books on this subject is Hostile Habitats – Scotland’s Mountain Environment: A Hillwalkers’ Guide to Wildlife and the Landscape by Mark Wrightam and Nick Kempe. If geology is more your thing, then Hutton’s Arse: 3 Billion Years of Extraordinary Geology in Scotland’s Northern Highlands by Malcolm Rider is well worth a look, and not just for the fantastic title. Finally, Chris Townsend’s encyclopaedic tome in Cicerone’s World Mountain Ranges series, Scotland, is also a superb all-round read.

Getting there

Arkle and Loch Stack (Stage 12)

If you’re travelling to the UK from abroad, you may need to obtain an entry visa. You can check this online with the UK Border Agency at www.gov.uk/government/organisations/uk-visas-and-immigration. Glasgow and Edinburgh both have large, international airports. Fort William, the southern end of the trail and the usual starting point, is accessible by train and coach. Trains to Fort William run from Glasgow Queen Street station (most UK mainline rail connections are through Glasgow Central, a short walk away). The train journey from Glasgow is an experience in itself, crossing the bleak Rannoch Moor before arriving into Fort William. The Caledonian Sleeper makes a nightly trip from London to Fort William, with various stops en route. For more details see www.scotrail.co.uk. Cape Wrath is generally reached by train from Inverness to Lairg and bus from Lairg to Durness or Kinlochbervie. For more detailed information see ‘Access to and return from Cape Wrath’ below.

Getting around

The remoteness of much of the route means that there are a limited number of points at which you can join or escape. Strathcarron is on the Inverness to Kyle of Lochalsh (Skye) train line: for information about trains see www.scotrail.co.uk. Shiel Bridge, Kinlochewe, Dundonnell, Ullapool, Inchnadamph, Rhiconich, Kinlochbervie and Durness all have bus services. Traveline Scotland (www.travelinescotland.com) is an invaluable resource for planning journeys – it even has a handy journey planner app for smartphones. The Royal Mail used to operate a Postbus service in the area. For a small fee you could share a minibus with a friendly postie and a few sacks of mail. At the time of writing these services have all but disappeared, and the remaining routes do not intersect with the trail.

Access to and return from Cape Wrath

Cape Wrath itself is inaccessible by direct road. A bus and passenger ferry service runs from the beginning of May every day until the end of September, weather, wind, tides, demand and military operations permitting. It crosses the Kyle of Durness and brings visitors from Keodale (just outside Durness) to the Cape and provides walkers with a handy means of escape without the need to backtrack to Kinlochbervie. The ferry service is operated by John Morrison (01971 511246). The bus service is operated by James Mather (01971 511284, 07742 670 196, james@visitcapewrath.com). Details of the services, particularly during MOD exercises, should always be checked in advance. Other useful sources of information are the Tourist Information Centre at Durness (01971 511368) and www.visitcapewrath.com.

In the months of May and September the first ferry leaves Keodale at approximately 1100 each day, including Sundays (the crossing takes about half an hour). There is usually an afternoon sailing leaving Keodale between 1330 and 1400. Throughout June, July and August the first ferry leaves at around 0930 on weekdays and Saturdays, services then run throughout the day on demand. On Sundays throughout the season, the first ferry leaves at 1100, with the last return sailings in the late afternoon. At the time of writing, the adult single fare from the Cape Wrath lighthouse to Keodale was £9.50 inclusive of ferry and minibus (for the latest information see www.capewrathferry.co.uk).

Outside of the main season, there is no real alternative but to retreat to Kinlochbervie. If you are desperate to reach Durness, you can follow the 4x4 track to the ferry crossing (about 11 miles, perhaps using Kearvaig bothy as a stopping point) before heading inland around the Kyle of Durness, but this is very rough ground. A bus service leaves Durness at 0805 (Monday–Saturday), calls in at the Post Office in Kinlochbervie at around 0855 and then goes onwards to meet the Inverness train at Lairg. More information is available at www.thedurnessbus.com. It is also advisable to check this service locally as the time and location of departures can vary. In summer months, direct coach services to Inverness may be available. For more information about reaching Durness see www.travelinescotland.com and www.visitcapewrath.com. The land and buildings at Cape Wrath were put up for sale by the Northern Lighthouse Board, their current owner. The land is subject to a community right to buy notice, and concerns that the Ministry of Defence might acquire the land and restrict access seem to have subsided. For the latest information check www.capewrathtrailguide.org.

When to go

Blizzard hits, Glen Oykel (Stage 10)

April, May and June can be ideal months to walk the trail as the days are long, the midges less prevalent and there can be spells of fine weather (although this being Scotland you should go prepared for anything). September and October are also good, but there may be diversions due to deer stalking and military operations at the cape. In July and August the days are superbly long and the weather can be glorious, but the midges will be in full flight. The limited accommodation along the trail may also be fully booked at this time of year. An attempt outside these months is possible but will require a good deal of skill, experience and expertise in the mountains. You may need specialist equipment (crampons, ice axe) and you’re likely to encounter heavy storms, very cold conditions and as little as six hours of daylight, making a daily distance of 20km around the practical limit. Be prepared to abandon your journey and be fully aware of foul weather route alternatives.

Accommodation

Benmore Lodge (Stage 10)

There is generally not a great deal of choice in this part of the world and availability is very much dependent on the time of year. While it’s technically possible to walk the route without carrying a tent, using a combination of bothies and other accommodation, it’s not prudent to do so. Bothies can occasionally be full to bursting, and you’ll lack the flexibility to vary your days if you’re feeling tired. Given that some stages are pretty remote, a tent is also an important part of mountain safety should one of your party get injured.

Accommodation listings are usually the first thing to go out of date in any printed guidebook. A current list is offered here as Appendix B, but you should also consult the constantly updated accommodation listings maintained at www.capewrathtrailguide.org/accommodation. In many places along the route accommodation options are very limited, if they exist at all, so it’s a good idea to book in advance, especially in summer months. Many of the more remote establishments close during the off season (typically October to March). Accommodation lists can also be obtained from VisitScotland (0845 2255121, www.visitscotland.com). Good, inexpensive accommodation is also available from the Scottish Youth Hostel Association (www.syha.org.uk) or the many independent hostels and bunkhouses (www.hostel-scotland.co.uk).

Bothies and the Mountain Bothy Association

The mission of the Mountain Bothy Association is ‘to maintain simple shelters in remote country for the benefit of all who love wild and lonely places.’ Even if you are planning to camp or use hotel/hostel accommodation along the trail, it’s a good idea to have an awareness of bothy locations in case of emergencies or foul weather. In times gone by, bothy locations were not shared widely and only available with MBA membership. These days the MBA displays bothy locations on its website, however all the charity’s maintenance work is carried out by volunteers and it relies on membership to continue its work. A full membership subscription costs around £20 per year, available at www.mountainbothies.org.uk.

Bothies work on a system of trust and respect which breaks down when people don’t abide by a few simple rules:

Leave the bothy clean and tidy with dry kindling for the next visitors

Make all visitors welcome

Don’t leave graffiti or vandalise the bothy

Take out all rubbish which you can’t burn

Don’t leave perishable food

Bury human waste well away from the bothy and any water sources

Make sure the doors and windows are properly closed when you leave.

Not all bothies are operated by the MBA, although their bothies tend to be the best cared for. Some estates also have bothies (for example Glenfinnan), offering varying levels of comfort. Some even have flushing toilets, although this is a rare luxury. Bothies are a unique part of walking in the Scottish Highlands and a rite of passage well worth experiencing. There are few better things than arriving at a remote bothy dripping wet from a howling storm to find a glowing fire ablaze in the hearth and a few fellow mountain lovers with whom to swap far-fetched mountain escapades. That said, bothies can sometimes be cold, rather spooky places if you’re on your own or don’t have fuel for a fire (most areas around bothies are stripped bare of usable wood) so you may prefer the warm solitude of your tent. Bothies that are on or close to the route or route variants are listed in the relevant route sections, and in Appendix B, with their grid refs.

Safety

Finiskaig River (Stage 3)

The Cape Wrath Trail crosses some of the remotest country in Britain, so you must be largely self-sufficient. At times you may be a day or more away from the nearest road, let alone help. For each day plan an escape route in case something goes wrong, or you cannot continue as planned (for example an uncrossable river).

Dangers you may encounter include:

Sudden weather changes – mists, gales, rain and snow may move in more quickly or be more severe than forecast (always have a refuge and escape route planned)

Impassable rivers due to heavy rain (have an escape route or the ability to camp and wait for the water levels to subside)

Ice on the path – a distinct possibility early or late in the year (carry and know how to use an ice-axe and lightweight walking crampons if these conditions are likely)

Excessive cold or heat (have the clothing and equipment to cope)

Exhaustion (recognise the signs, rest and keep warm)

Passage of time (allow plenty of extra time in winter, in poor weather and over rough terrain).

River crossings

River Oykel, near its source (Stage 10)

River crossings are one of the greatest hazards on this route. In normal conditions, most mountain streams and rivers in Scotland are wide and shallow, with pebbly bottoms, making them relatively safe and easy to wade across where there are no bridges (a common occurrence given the remoteness of much of the trail). But a small burn that can be easily crossed in dry weather can quickly turn into a dangerous torrent after sustained rain. Crossing rivers and streams at the wrong time, in the wrong place can and does kill people and this unpredictability makes it impossible to provide warnings for all crossings. The route has been designed to avoid crossings that are known to be dangerous in very wet conditions. Potentially tricky crossings are noted but you should assume that all river crossings in wet weather will be more difficult and factor this into your timing and route planning.

After a long day in rough country, particularly if you’re behind schedule, the temptation can be to ‘plough through’ a river. But if you’re unsure about the safety of any crossing, a detour upstream will generally turn up either a safer crossing point or a bridge that isn’t marked on the map. If in doubt, find somewhere else to cross or do not cross at all, as rivers subside quickly when the rain stops. With common sense and by familiarising yourself with some basic river crossing techniques, you should be able to deal with anything you encounter on this trail. Consider using walking pole(s) to provide additional stability when crossing. The British Mountaineering Council (BMC) provides an excellent guide to river crossings as part of their Hill Skills series: www.thebmc.co.uk.

Given the number of river crossings, it’s also worth giving some prior thought to how you’ll deal with wet feet. This can be a real problem, with blistering from damp footwear being one of the main reasons people have to abandon the trail. Some choose to strip off their socks and cross in boots alone. This approach seems to hold limited advantage as sodden boots soon lead to sodden socks. Others carry a lightweight pair of plastic sandals that can be worn for river crossings, thus keeping boots and socks dry.

Personally I find the process of trying to keep your boots and socks dry time consuming and fairly fruitless given the sheer amount of bog and water to be crossed. My favoured approach is to use Gore-Tex socks and a good gaiter. Whilst these won’t keep you completely dry, they prevent the worst of the water getting at your feet and greatly reduce the amount of time spent faffing about at the edge of burns.

Pests

In general the flora and fauna in this part of the world are unlikely to cause you any harm, but there are a few things you need to look out for.

Ticks

The incidence of Lyme Disease caused by a bite from a tick, a small parasite, has been on the increase in Scotland. It is a serious and potentially fatal disease. Ticks are common in woodland, heathland and areas of Scotland where deer graze. Insect repellent and long trousers are the best prevention and you should check yourself regularly. Ticks can be removed by gripping them close to the skin with tweezers and pulling backwards without jerking or twisting. Don’t try to burn them off. Symptoms of Lyme Disease vary but can include a rash and flu-like symptoms that are hard to diagnose. Most cases of Lyme Disease can be cured with antibiotics, especially if treated early in the course of illness. The Mountaineering Council of Scotland has a useful tick advice video on its website: www.mcofs.org.uk.

Midges

Midges are a voracious scourge of the western Highlands, at their peak between the end of May and early October. There are more than 40 species of biting midge in Scotland, but luckily only five of these regularly feed on people. Even so, their bite causes itching and swelling that can last several days. Unless you’ve experienced the sensation of being ‘eaten alive’ by a cloud of Scottish midges, it’s hard to understand just how unpleasant they can be. In summer, they can generally be relied upon to spoil beautiful lochside sunsets. Unfortunately the Cape Wrath Trail passes through through the very heart of midge country. The only real prevention is insect repellent or physical barriers such as head nets. From experience DEET based repellent products work most effectively, although they have an unpleasant aroma of chemicals and should be kept away from plastics and sensitive fabrics like Gore-Tex. Citronella candles also work well and many people swear by Avon Skin So Soft (available from www.avon.uk.com).

Some people maintain that light-coloured clothing also keeps midges at bay, although I haven’t personally noted a particular preference for the high fashion hues of modern outdoor gear. Unfortunately even when repellents are used without a physical barrier such as a net, midges will still land and crawl on you. The good news is that midges can’t fly in even the gentlest of breezes, which are not usually in short supply in this part of the world and they dislike strong sunlight (should you see any). Such is the impact of the Scottish midge that it now has its own forecast and Apple iPhone app. For more information see www.midgeforecast.co.uk.

Weather

River Dessarry (Stage 3)

The northwestern Highlands of Scotland is one of the wettest places in Europe, with annual rainfall of up to 4,500mm (180 inches) falling on as many as 265 days a year. Due to the mountainous terrain, warm, wet air is forced to rise on contact with the coast, where it cools and condenses, forming clouds. Atlantic depressions bring wind and clouds regularly throughout the year and are a common feature in the autumn and winter. Like the rest of the United Kingdom, prevailing wind from the southwest brings around 30 days of severe gales each year. The combined effect of wind and rain can make walking hazardous at times, even in relatively low-lying areas, so you should always have an escape plan.

Emergencies

In an emergency, dial 999, ask for the police, then state that you need mountain rescue. Be ready to give a detailed situation report – the mnemonic ‘CHALET’ may help you remember vital information under pressure:

Casualties – number, names (and, if known, age), type of injuries (for example lower leg, head injury, collapse, drowning)

Hazards to the rescuers – for example, strong winds, rock fall

Access – the name of mountain area and description of the terrain. It may also be appropriate to describe the approach and any distinguishing features of your location (for example an orange survival bag). Information on the weather conditions at the incident site is also useful, particularly if you are in cloud or mist

Location of the incident – a grid reference and a description. Don’t forget to give the map sheet number and state if the grid reference is from a GPS device

Equipment at the scene – for example, torches, other mobile phones (including their numbers), group shelters, medical personnel

Type of incident – a brief description of the time and apparent cause of the incident.

If you are unable to telephone for help, use a whistle and repeat a series of six long blasts, separated by a gap of one minute. Carry on the whistle blasts until someone reaches you and don’t stop because you’ve heard a reply, as rescuers may be using your blasts to help locate you. At night use a torch to signal in the same pattern.

A service now enables texts to be sent to the emergency number 999 when voice calls cannot be made, but where there is sufficient signal to send a text. To use the service you’ll need to pre-register via a text – send ‘register’ to 999 and you’ll get a reply with further instructions. If using the service in an emergency, you should wait until you receive a reply from the emergency services before assuming help has been summoned. Further details, including guidelines on how to register, can be found at www.emergencysms.org.uk.

Money and communications

It’s a good idea to carry a supply of cash with you as cards are not universally accepted and cashpoints are few and far between. Cashpoints can be found in Fort William, Kinlochewe, Ullapool and Kinlochbervie (located in the Spar supermarket at the harbour).

Post Offices can be found in the larger towns (Fort William, Strathcarron, Kinlochewe, Ullapool and Kinlochbervie) and most small villages have post boxes. Post Offices may also hold parcels for collection (they need to be addressed to the Post Office itself and marked ‘Post Restante’ and you’ll need photo identification to collect: see www.postoffice.co.uk for more details). Most hotels and hostels will also hold parcels for residents if you ask them in advance.

Mobile phone coverage is distinctly patchy in the northwest Highlands and shouldn’t be relied upon. If you’re worried about mobile phone coverage, ‘pay-as-you-go’ SIM cards for the main UK networks can be bought cheaply and used in ‘unlocked’ mobile phones to ensure you can connect to any available network. Internet data access via mobile phone is rarely possible outside larger areas of civilisation and even then it’s likely to be a slow GPRS connection rather than 3G or 4G. An increasing number of hotels offer internet access via wi-fi.

English is spoken throughout the Scottish Highlands, although the broad local brogue can sometimes take a bit of getting used to if English is not your first language. You may also encounter some Gaelic, a beautiful but rarely spoken language.

Preparation and planning

Stand of pines, Glen Dessarry (Stage 3)

It is with some justification that the Cape Wrath Trail is regarded as the toughest long-distance backpacking trail in Britain. Dotted here and there, you may come across signs that guard the entry to particularly remote sections: ‘Take Care – You are entering remote, sparsely populated, potentially dangerous mountain country – Please ensure that you are adequately experienced and equipped to complete your journey without assistance’.

It is hard to improve on this pithy warning – this is rough, unforgiving country that should not be under-estimated. There are no pack carrying services and often there are not even any clear paths, only bogs and leg-sapping terrain. Limited re-supply points require self-sufficiency for much of the journey, and there will be stretches during which you’ll need to carry many days’ supplies. This is absolutely not a route for beginners or those unfamiliar with remote, rugged mountain areas. It is in a totally different league to other Highland trails like the West Highland Way, where civilisation is never far away.

The journey usually takes two to three weeks and the cumulative effect of sustained daily exertion is substantial. Don’t be afraid to start with a few shorter days and build rest stops into your schedule. To borrow from the lexicon of football managers, this is a marathon, not a sprint. With a decent level of overall fitness and mountain experience you should be able safely to enjoy your weeks on the trail.

What to take

The choice of equipment for any expedition is intensely personal. On such a long and arduous trip, there is a temptation to err on the side of lighter weight, but given the likelihood of harsh weather at any time of year, you’ll need to strike a sensible balance between weight and function. The list below is not designed to be comprehensive, but offers a broad outline of the kind of equipment you’ll need to be considering. For more information about expedition kit see www.capewrathtrailguide.org.

Camping and carrying