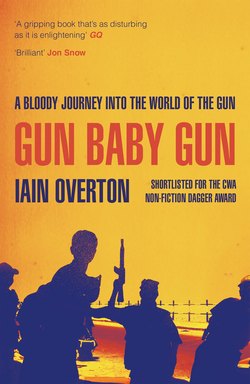

Читать книгу Gun Baby Gun - Iain Overton - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. THE GUN

Brazil – a murder in São Paulo – a child’s sorrow and a dead mother – the descent into a police arms cache – a revelation – a journey conceived – Leeds, UK – a secret museum and a meeting with an expert – to a Swiss canton to visit an oracle

It began with a death.

The five-year-old had lain alone with his lifeless mother all night long, curled up at her cold feet. It was only when the thin light of dawn lifted some of the darkness from the bedroom that the neighbours had heard the boy’s cries. And only then did people realise what had happened in those sunless hours before.

The bullet had entered the left side of the young woman’s temple and exited at the back of her head, splattering flecks on the leprous wall. There had often been wild-voiced arguments in that cramped house, but no one ever thought it would come to this.

After the boy was found the police arrived quickly, but the murderous lover had already fled that Brazilian city and, like the gun he had used, he was nowhere to be found.

By the time we reached the quiet roadside home the child had also been spirited away, covered in a blanket – lifted from his dark pietà and carried out into the light. His mother was still inside.

Cars passed, leaving São Paulo for the north, and we stood awkwardly and watched them go. They slowed down and watched us too, a huddle of cops and a documentary crew crowded beside a white ambulance that was never really needed. A dog barked in the distance, and I took out my video camera and walked inside.

The dead woman had run a small shop out the front, and it was filled with packets of coloured sweets and warm bottles of luminescent drinks. On the counter was a tray of Catholic pendants, which she had sold to the weary lorry drivers who would stop here. But these plastic icons had not helped her last night, and now she lay beyond, past a dusty glass counter, down a narrow corridor, there in a pool of silence.

They say death smells sweet. That’s what I thought as I walked into her bedroom. A taste touched my mouth and reminded me of the orange-tinted bottles that lined the shop’s walls or the citrus chocolate puffs that lay neatly arranged in their shiny little packages. The air was thick with this smell. It had been over twelve hours since she had died, and this was the start of summer.

Her name was Lucicleide, and she was naked. I was not expecting that, but death rarely grants us dignity, so her breasts hung to the side and the rest was uncovered. There was not much blood, save for a smear above her pinched, sallow face. Finding a corner, I set up my tripod and got to work; the police did not tell me to stop filming, but by now I was not even sure why I was doing this. My footage would never end up on the evening bulletins. The film I was making with Ramita Navai – an Anglo-Iranian journalist who was used to witnessing such things – was about the toll of violence in one of Brazil’s deadliest cities, but Britain’s Channel 4 News could never show such intimate and murderous detail.

I felt I had to do something, though.

So I focused on her unfurled hands and on the trinkets that lined the top of her chipped cabinet and shifted the lens onto the face of a purple bear I imagined her lover had once bought her. And the whirr of the tape in the camera took the edge off the awkward quiet of the room. I carried on filming until the forensic examiners wrapped her in a heavy blanket, and all I could think of as she was lifted heavily up, covered like her son had been, was how hot it was to have such a blanket to sleep under.

We followed the body out into the light and slipped back into our car. Then, after waiting for the coroner’s van to slide away, we too pulled out and drove south, following an unhurried squad car back to the city’s police headquarters. And none of us spoke.

The building was low-slung and squat, built in the way Brazilian architects love: concrete, slats and shutters. Municipal chic that was made markedly less chic and more threatening by the armed police stood behind its long glass front. The steps leading up to it were broad and shallow; they twisted in an arc and made the walk to the doors of justice a slow one.

An image of São Paulo as a dystopian city, something out of a Judge Dredd comic, came to mind. This was its rigid heart of order and legal retribution, but policemen stood, their arms cradling dull metallic weapons. The reason for this was clear. In one year alone there were over a thousand gun murders in this city, in waves of crime so violent they had caused schools to close and municipal bus routes to change.1

It was small wonder that this governmental building was so foreboding. Dozens of police officers had been killed, caught up in the endless drug wars that blighted this land. The guards at the entrance were taking no chances. They were heavily armed – police assault rifles slung across their riot shoulder pads and bulletproof vests lying underneath.

Passing through scanners and scrutiny, we emerged on the other side. There we were met by Colonel Luiz de Castro. A short man with dark, tightly cut hair, a firm jaw and a precisely ironed shirt, he looked like someone born to be in the service of the state. Greeting us with an iron handshake, he was quick to address why we had come here: to see São Paulo’s seized-gun repository.

‘A few years ago we had a gun amnesty,’ he said as if delivering an order, his voice a staccato drumbeat. ‘Here we have about 20,000 weapons confiscated or handed in. We offer between $50 and $100 for each one.’

The colonel spun on a heel and led us at pace down a long corridor, lit by naked and glaring fluorescent strips. The sandpaper walls here were bare and the floor scuffed, and as we descended slowly into the sodium-coloured belly of this bureaucratic beast, the colonel walked ahead, his boots sounding the mark of his passage. Then he stopped at a grey door and motioned us inside. Beyond lay a small room with a few computer terminals, in front of which sat uniformed officers. They were inputting data and looked up at us with the eyes of people whose lives were spent in rooms without sunlight. Across from them lay a caged door.

The colonel called out, and a shadowed face appeared; keys were turned, and the door swung outwards. We walked into the semi-darkness.

Beyond lay thousands of guns. Every surface was filled with them – the walls lined with wooden, narrow boxes, like a mail-sorting office, each pigeonhole containing a gun with a small paper label attached. Space here had run out long ago, and the guns spilled out onto the counters and the wooden chairs that spread across the floor. A door led on to another room and then another, and the scene was the same in each.

There were semi-automatics from North America; hunting rifles from China; a 9mm pistol from Germany; an old blunderbuss from England. There were home-made handguns and high-tech machine-guns. Black guns so corroded with time you imagined them wielded by slave owners in long-shut-down plantations. There were even some with Polícia stamped on them, because when Brazilian gangs kill a policeman the prize is that downed cop’s sidearm as well as his life.2

Then it struck me how, like the clichéd six degrees of separation, this graveyard of guns was somehow more significant than just what was visible in this narrow space. Each gun here, either through maker or victim, shooter or seller, was somehow linked to a bigger story – each connected to the outside world in a deeper, more nebulous way.

Here were revolvers bought with taxpayers’ money and ordnance left over from long-forgotten wars. Police pistols and army handguns, sports rifles and hunting shotguns from all over the world, many of them tainted with the stain of murderous deeds. The microcosm of life – of law and protection, violence and vengeance, leisure and provision – was laid out in these shadows.

In a sense this lair of guns was a symbolic image for all of the human rights tragedies I had ever been trying to explain as an investigative journalist and a human rights researcher. And the idea for this book was conceived in that moment – a desire to trace the gun’s pathway from its metallic cradle to its blood-tinged grave. A journey to discover the lifecycle of the gun and, in so doing, to understand a little bit more about death and maybe, even, a little about life.

There are almost a billion guns in the world – more than ever before. An estimated twelve billion bullets are produced every year. Over a hundred countries have their own gun industries, and twenty nations recently saw children carrying guns into conflicts. In this new millennium, AK47 rifles have even been sold for as little as $50.3

These are hard facts that have harder consequences. And yet, despite how shocking these numbers are to hear, before I began to research the world of the gun, these were facts I did not know. Perhaps this is because the gun remains all too often forgotten in our media and news. Throughout my career I had frequently reported on the harm wrought by firearms, but I had never actually done a report on the gun itself. It was a bit like the face of evil: you knew it was there, but you felt a little foolish mentioning it. With other weapons, it was different. ‘A kitchen knife? He was beheaded? My God, that’s terrible.’ But with a gun it was more like: ‘Of course there’s a gun.’ Guns were just there, remarkable but unremarked upon.

In Lucicleide’s shaded bedroom, I had seen one face of the gun: the way it can take a life. In São Paulo’s police headquarters, I had seen another: the way the police seek to contain and control guns. But these were isolated images, scattered pieces. Seeing them on their own did not answer questions such as: Who made those guns? How did those police pistols end up being used in a killing? Who profited from the sales of those Uzis?

I knew some of the answers. The assignments and campaigns I had worked on had been diverse enough to allow this. War correspondents usually just witness the harm that guns cause. Arms-trade campaigners often focus on the world of immoral governments. Investigative journalists seek to expose corrupt gun sellers. I had earned a living carrying out all of these roles, and so had seen glimpses of such things and more. Reporting on trafficked women in eastern India or filming the slums of Buenos Aires, seeing the impact of violence in the borderlands of Mexico or recording the tense diplomatic stand-offs between China and Taiwan, I’d seen the gun in many of its varied colours. But there were gaps. I knew little about the world of hunters. I had never met a sniper. Never been inside a gun factory. What I wanted was to bring these parts together – to see the whole, the gun as a sum of its many parts.

Of course, such an undertaking was ambitious. People would suck in their breath when I told them what I wanted to do. Certainly it was global. Too much of the media has fixated on the US’s relationship with guns and that alone, but I wanted to take in the wider view. Guns in the US showed, to me, just the tip of a bloody iceberg.

This was, then, a journey born from both memory and new experiences, one where I had to revisit worn notebooks as well as tread the carpets of soul-sucking airports on my way to yet another killing. And through doing so I sought to weave a complete tapestry of the impact of guns on our world – where the thread of a moment lived in one city might unexpectedly find itself tied to a visit planned in another, far away.

The view I sought was certainly too big to take in without some sort of plan, so I decided to divide my research into the communities the gun impacted. There were those directly harmed by firearms – the dead, the wounded, the suicidal; those who used guns to exert a form of power – murderers and criminals, police and armed forces; the people who used these weapons for pleasure – hobbyists and hunters; and those who sought to profit from their sale – traders, smugglers, lobbyists and, ultimately, the manufacturers. I planned to approach each community in turn, merging memories and interviews, new trips and research, to grasp fully what it was like to live, and die, under the gun’s shadow.

To begin, though, I wanted to understand a little bit more about firearms themselves – to see their historic place in the world, how they evolved and how they have influenced the unfolding of history. So I arranged to travel northwards from my home in London, to the largest museum collection of guns in the world – to the Royal Armouries in the English town of Leeds.

The gun collection at the British National Firearms Centre started almost four hundred years ago. It was originally dreamed up by King Charles I, a hapless monarch who wanted to give some uniformity to his kingdom’s procurement of arms. Since then, the centuries have added to the collection; today the armoury boasts the largest number of unique rifles and handguns kept anywhere under one roof. If there was one place to begin a deeper understanding of the world of the gun, this was surely it.

So, on a blustery day in spring, the senior curator there, Mark Murray-Flutter, agreed to meet me at the entrance of the public museum. A large and effusive man, he greeted me in a flurry of great strides and smiles. He held out his left hand to shake me by my right and it confused me; I looked down. Instead of flesh I saw a prosthetic limb. Ex-military, I thought: the price a man pays for being too close to guns. He ignored the look on my face.

Without explaining where we were going, Mark turned and led me away from the municipal grey building at a brisk place, his tie fluttering. We walked down a wind-filled road under heavy, tea-coloured clouds and there, through an unnamed and unmarked door, we crossed into a windowless space lined with steel and concrete. Beyond was a metal detector and an armed guard asking, through a bulletproof window, if he could see my passport. Then there was a body search. Finally, we entered a cavernous space where the public rarely goes.

‘Here you are,’ Mark said, a smile widening on his face. ‘Where it all is.’

Guns. Thousands of them. They filled the cavernous room like squat metal insects, sleeping before an ugly dawn – hunched, silent and demonic. Under the chrome light you could see row after row of every type of firearm imaginable. There they were, oiled and fierce on the floor. There, neat and polished on racks. Hung on wall brackets, put away on shelves, slid deep into recessed drawers. It was like Borges’s infamous library, but here were guns not books – over 14,000 in steel and wood and brass.4 And here, unlike the police repository in Brazil, the guns were ordered and neat – their potential anarchy contained.

It smelled like history: gun oil and the ghosts of cordite. These weapons spoke of past wars and long-forgotten conflicts, because the curators had tried to get their hands on every type of gun ever produced, within reason. When the British used to mass-produce rifles they would dispatch the prototype – the first edition – to the armouries. There they were stamped with a thick layer of copyright sealing wax and stored away. Elsewhere machines got to work and churned out copies in their millions, and the prototype’s offspring wound their way to the foothills of the Himalayas and the steaming jungles of Africa, as this little nation of shopkeepers traded and slaughtered its way into Empire.

The origins of all of that violent shame and bloodied history could be seen here; and this was just the collection of Britain’s guns. There were others, too. Here was the United Nations of firearms – it was almost a case of naming a country and a gun from there could be conjured up.

‘The best way to think about this place is as a library, but instead of having books you have guns,’ Mark said, offering me a cup of tea. A reasonable, softly spoken man, he was not into weapons, he explained. At least not for what they were per se; rather this wounded scholar liked what they represented. He was a social historian, fascinated by how firearms fitted into society. If he had one interest, it was their ornamentation, their decorative appeal. In this way he saw himself as a benign curator – not a man who would view this room in terms of gun control, how many lives taken, how many liberties defended. Rather, he was interested in their meaning.

‘I’m fascinated by the use of firearms as a status symbol, as diplomatic gifts, as love tokens,’ he said, education in his voice. ‘How they can show people you have arrived. Certainly this is true in the world of those who own shotguns – the higher you go up that economic ladder, the less it’s about the cost, the more it’s about the ostentatiousness of the design. The Russian oligarchs, the Mexican drug gangs who gold-plate their guns, they are trying to show that they are all-powerful.’

We spoke about facts. But, in a way, when it came to Mark giving a broad introduction to guns, there was not that much to say. In this world the devil was in the detail. What calibre, what model, these were finer points that many gun enthusiasts fixate on – but not ones that captured my attention. I couldn’t get excited about the small tweaks made to a handgun to sell a newer, deadlier version. I was more interested in what these guns did.

Just as well, really, because when it came to the basic physics of the firearm, Mark said things hadn’t really changed since the fourteenth century. All a gun needs, he explained, is a barrel, a missile, a means of projection, a form of ignition and a way to point it. All the developments since these principles were first conceived were pretty much just perfecting this process.

‘They may be lighter, more compact, but they are fundamentally the same,’ he said, leaning forward over his mug. ‘There have been two major step changes in the development of firearms. The development of the self-contained cartridge in the early nineteenth century and the gun that can fire automatically – developed by the British – by Maxim.’ Perhaps this is what lies beneath the enduring popularity of guns, I thought. The fact that there’s an alluring simplicity to how they work.5

Finishing his tea, Mark rose from the table and told me to follow. He handed over a pair of white gloves, and then, like vicious mime artists, we entered the stacks. There he began to pass me rifle after rifle, with a disconcerting casualness.

Closest to us was a Gardner gun – a five-barrelled, hand-operated machine-gun, fed from a vertical magazine. As the crank turned, he explained, a bullet was loaded into the breech, the bolt closed, and the gun fired.6 It was part of a major landmark in the development of the gun. There were even men who saw civilisation’s face in this mechanised operation purely because the Gardner gun worked on the principle of serialisation. As such the machine-gun was seen, by some, as a product of a rational culture. By default, cultures that could not create such a killing weapon were deemed less civilised, and so open to imperial rule.

Such men would have been impressed here, because in this fortified chamber the walls were lined with sub-machine-guns. Anti-aircraft guns, first designed to combat the use of observation balloons in the American Civil War, also stood to the far left. To the right there were Chinese DShKs; a gun mounted on wheels, called, affectionately, ‘Sweetie’. These stood beside a low line of recoilless rifles once used as tank busters. And there, on the end, were Russian rifles that fired underwater. Civilisation’s progress laid out in deadly metal.

These guns all told a story in their own way. They spoke of how rifles and pistols had turned the course of history. How the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo unleashed the First World War. How the killing of Martin Luther King pushed the US closer to equal race rights. They spoke of how the gun has helped bring advances in industrial production methods and advanced modern medicine. And they all spoke of death.

There, on the far wall, one rack held a familiar shape: the long, curved magazine, the wooden stock, the iron sights. A gun that could fire automatically like a machine-gun, or could let loose single shots, like a sniper rifle; that could be chucked in a river and dragged in the mud and still not jam; a weapon so popular that tens of millions of them have been made. It was the Kalashnikov or AK47, the most famous and the deadliest gun in the world. So practical and lethal has it proved in modern conflict that it has featured on the coats of arms of Zimbabwe, Burkina Faso and East Timor. There are statues to it in the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt and on the dusty plains outside Baghdad in Iraq. It’s had a cocktail named after it and is a drinks brand in its own right, sold in bottles moulded in its iconic shape. Some parents have even named their babies ‘Kalash’, so deep has been its global allure.

Mark extended a white-gloved hand and pulled down one from China.

‘That’s a type 56,’ he said, putting the barrel close to his face. ‘Yes, it’s from a northern province. This folding stock was new.’ It came from State Factory 66, just one of 15 million of its type produced there since the 1950s. He pulled out another; from 1981, he told me, Chinese as well. His finger traced the first two digits of the serial number. There are about ninety variants of this type, he said, and pointed at a vicious black derivative – one with a hard metal folding stock. ‘East German.’ He needn’t have said any more. It looked East German. There was nothing funny about it.

You could see national traits in many of these guns, however subtle. The Finnish version had a certain chic to it – a tubular stock that evoked northern European woods and candles. The Egyptian one came with a small tree stamped on it, made especially by the Maadi company there on old imported Russian machines. The North Korean one looked cheap and sorry for itself – a small communist star on its base. The Red Young Guard, a force made of up fifteen-year-old Korean students, used this model; it was certainly light enough for their malnourished bodies. Then there were AKs from Pakistan, from Russia, from China – sometimes a dozen from one country alone. There was even an old Viet Cong one – the rifle that proved the ultimate battlefield leveller against the might of the American army.

The one that caught my eye, though, was the gold one: a glittering metal-plated AK designed to commemorate the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988. Saddam Hussein handed them out as gifts – a sort of oil-bling chic in limited edition.

‘I’ve got to hold that one,’ I said. Something in me was feeling the pull of history, the uniqueness of this whole situation. I wanted to get my picture taken with it, wearing too-large shades and an open-necked shirt.

‘Very Arab,’ Mark said, and eased it from me back onto the shelf.

He took me to another rack. Here was a Lebanese M16 semi-automatic – this one made by Colt USA. Beside it was an M16 seized from the IRA – complete with a filed-down serial number. Next to it was a line of futuristic and squat black Belgian FN F2000s – a weapon so beloved of Colonel Gaddafi’s murderous forces. There was ingenuity to all of these; as you moved along the line many had small modifications that improved on the design of its neighbour.

‘If I find a new way of protecting myself, you will find a new way of preventing that,’ Mark said.

Then, with a certain reverence, he pulled out an 1805 model of the Baker Rifle – a rifle used on the fields of battle at Waterloo in 1815. It weighed about the same, he said, as the British army’s SA80 rifle today: ten pounds. I held it and imagined a scared seventeen-year-old in rank and file clutching its wooden stock with child’s hands, fearing all that lay ahead.

We moved away from the military weapons and on to a rack of sporting guns, notable for their provenance and their price. Mark pulled out a hunting rifle – a .375 H & H Magnum – carried by a companion of President Roosevelt on an African hunting trip in 1909. A similar one to this fetched almost $32,000 at auction. Next to it was an M30 Luftwaffe Sauer & Sohn Drilling, the world’s most expensive survival firearm. A three-barrelled shotgun complete with a Nazi swastika, it was designed to help Germany’s Luftwaffe pilots avoid capture. You could see Hermann Goering’s obsession with beauty and craftsmanship in this elegant and totally impractical weapon. And just as I thought that you couldn’t get more expensive than that, Mark showed me the most pricey gun in his collection: a bespoke Arab commission of a Smith & Wesson Model 60, made in powder blue and coated in 984 diamonds. It costs over £120,000.

But this opulence was not the thing to catch my eye. Rather, there, nestled in a rack among some ageing rifles, was the prototype for the late nineteenth-century Magazine Lee Enfield Rifle. In army terminology it was the MLE, or ‘Emily’, the rifle clutched by thousands and thousands of British soldiers as they marched to their deaths in the First World War, and one of the first of millions made. It was also the rifle that had introduced me to the world of the gun – the one I learned to shoot with in the Army Cadets.

Before I could get too distracted, Mark moved us on to a small and nondescript chest of drawers – a cabinet of curiosities. Drawer after drawer of discreet guns used by the secret service were opened. There was the famous James Bond Walter PPK, 9mm;7 a Parker Pen gun; a ‘sleeve’ gun designed to be tucked up a jacket; guns disguised as lighters, rings, pagers, belt buckles and penknives. All of them innocuous and all capable of killing.

‘Squirrelly,’ Mark described them. They certainly captured the imagination – secret agents and honey-traps and the whiff of soupy rendezvous in the fog of East Berlin. We carried on, each rifle catching Mark’s eye taken out, examined and admired. So time passed in this space without sun or guiding light. It felt as if we were in a huge mausoleum – a tomb of arms. A feeling of claustrophobia started to form, and the buzzing overhead lights began to hurt my eyes. Then, suddenly, it was time to say goodbye.

I had one final question. I asked Mark about his hand. ‘Did you lose it in a shooting accident?’

‘No,’ he replied. ‘I was a Thalidomide baby.’ In the late 1950s the prescribing of a pill to combat morning sickness caused hundreds of babies to be born with defects. His false hand had nothing to do with a gun wound. He smiled and bade me farewell and, after another body search to make sure no secret-service pen guns had ended up in my pocket, I left.

Night was falling, and I walked away from this secret vault with its murderous contents, out into a drizzling, darkening northern city. A Thalidomide baby, I thought, turning up my collar. So much for assumptions.

I woke to the sound of an argument. The whores had been up all night, and the dawn was just hitting the sidewalks of Geneva; they were still short of a good night’s takings. Such things test the patience of anyone.

I pushed open the window and looked down. The pink neon strips of Le Player’s sex lounge shimmied in the lessening dark; the transsexuals, who had pushed their long legs out at the passing men, had left the kerb outside World’s Elite hours before, but the women from the Congo were still there. They knew what work really was and they whistled and plucked at the sleeves of men seeking comfort in the early morning. They were sweet-perfumed and hard-faced.

After Leeds I had come here, to Switzerland, to get my facts straight about how many guns there were in the world. The night before I had read that in 2007 it was estimated that there was about one gun for every seven people in the world; that police forces had about 26 million firearms; armies 200 million;8 and that civilians owned the rest: 650 million.9 These figures came from the Small Arms Survey – a Swiss-based organisation that lay about a mile away from where I was staying and which was my next port of call.

I had a meeting that morning with their chief, Eric Berman. With almost a billion guns out there, his job was to give some semblance of statistical order to them. He was, in a sense, a worldwide oracle on gun facts and figures. Definitely a man to meet. So I dressed and left the hotel, passed the cat-calling women and headed out to Geneva’s waking streets.

The Small Arms Survey was on Avenue Blanc, and the area could not have been more Swiss. The Survey’s office was tucked away in the same building as the Myanmar, Cape Verde and Tanzanian missions. Next door to them was a chocolate shop with an oversized cacao bunny in the window. Beside that stood a business school, a medical centre and the Swiss Audit & Fiduciary Services Company. It all had a sterility and orderliness to it that was a world away from the gore and blood that gun violence brings.

I rang the bell. Eric was called for. As I waited, I browsed the magazines on the waiting-room table: Defence News International, Security Community, Asian Military Review – bitter-edged titles. The same could be said of the photography on the walls. One showed bullet holes in a window overlooking a grimy industrial sprawl in La Vela Gialla, an Italian neighbourhood run by the Camorra mafia family. There was a photo of a drug dealer’s hand in Brooklyn, clutching a Colt Python .357 Magnum along with fifty bucks’ worth of five-dollar crack cocaine wraps. Then an image, black and white like the others, of Liberian youths clutching Kalashnikov-style assault rifles, wearing bandanas. They stared fiercely at the unflinching lens. Guns and their many faces around the world.

Eric appeared, shook my hand and led me to his office. We sat down, and I began to explain that I was writing this book about the world of guns and that . . .

‘You don’t have to butter me up,’ he said, and I was surprised. I thought this was going to be a nice conversation; he looked nice – slim, middle-aged, neat. He reminded me of one of those cautious editors you meet on British papers: clever without eccentricity, focused without shifting into obsessional.

‘The Small Arms Survey has many views on guns,’ he carried on, answering a question I hadn’t asked. ‘We don’t have a single view. My personal reason for doing this is very different from that of my colleagues . . .’ and he began to explain how the Survey is neither pro-armament or anti-gun. Then he stopped, looked at me and said, ‘Ask me a specific question.’

So I did. ‘How many guns are there in the world?’

But you can’t just give a number, he said. Eventually, after telling me how the Survey reviews 193 United Nation member states, and with all the caveats that go with not having access to decent data, he handed me three reports: ‘875 million was the global estimate.’ He then said that number could be higher – this figure was seven years old. He spoke of how secrecy surrounds military and law-enforcement figures, how the Survey has to estimate the number of guns some militaries have by looking at the numbers of soldiers at the height of a nation’s power, because when armies downsize their guns are often just put into storage. Such are the challenges of getting a bigger picture. But he did say one thing was certain: more weapons are produced globally each year than are destroyed.

I asked him if counting the number of guns owned by various militaries could help fuel an arms race between countries.

‘That’s a facile argument,’ he said, a spark of irritation deep in his eyes. I was intrigued by how defensive he was being. I told him so.

‘It’s hard to give you concrete answers,’ he said, crossing his arms.

‘There’s no intrinsic relationship between the quantities of firearms in a given place and the levels of violence,’ he said. ‘One can really skew one’s argument in favour or against gun control. You can pick and choose. You have to be very careful on this topic, as it is so easily manipulated and used. Some people just don’t appreciate the complexity of it.’

He saw me glaring back at him over my notebook, and he breathed out. You just have to be cautious, he told me. ‘Journalists can take a snippet of something you’ve said and use it to move an agenda forward, and I don’t want to get caught up in that.’

As he spoke, I realised this New Yorker, who had a map on the wall of a hitchhiking trail that he’d trodden years before through the Congo and who had lived in Israel and Kenya, Mexico and Cambodia, was not that dissimilar to me. Guns had propelled him around the world, and his view on them was as shifting as the sandy ground of facts he walked upon.

I had hoped to meet a guide – someone who could have showed me an intellectual and factual path in my journey into the world of the gun. But I’d met someone who refused to be rooted in one opinion, choosing instead ever-changing interpretations offered by ever-changing hard numbers. He told me the world of guns had changed him, that he now looks at data differently and he has to be more cautious in the words he uses to describe his Survey’s conclusions. Guns are inherently political, it was clear, and he strived for a consciously impartial voice.

He gradually relaxed and showed me his office. It was filled with softer things: humanity in baubles that had little to do with guns. A paperweight from the Central African Republic, a grave marker from Gabon, a stamp from the Republic of Guinea showing, surreally, Carrot Man from Lost in Space. An unopened bottle of Kazakh vodka rested on the shelf.

‘Make sure you write down that it was unopened.’ And I did, because in the world of guns you have to be careful with the facts, clearly.

After all, it’s a matter of life and death.