Читать книгу Facing the Anthropocene - Ian Angus - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

The earth is polluted neither because man is some kind of especially dirty animal nor because there are too many of us. The fault lies with human society—with the ways in which society has elected to win, distribute, and use the wealth that has been extracted by human labor from the planet’s resources. Once the social origins of the crisis become clear, we can begin to design appropriate social actions to resolve it.

—BARRY COMMONER1

In the past twenty years, earth science has taken a giant leap forward, combining new research in multiple disciplines to expand our understanding of the Earth System as a whole. A central result of that work has been realization that a new and dangerous stage in planetary evolution has begun—the Anthropocene. At the same time, ecosocialists have made huge strides in rediscovering and extending Marx’s view that capitalism creates an “irreparable rift in the interdependent process of social metabolism,” leading inevitably to ecological crises. These two developments have for the most part occurred separately, and despite their mutual relevance, there has been little interchange between them.

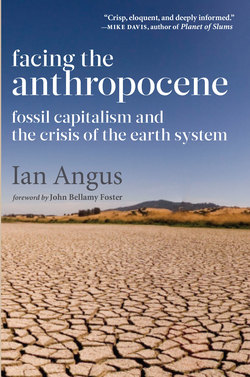

Facing the Anthropocene is a contribution toward bridging the gap between Earth System science and ecosocialism. I hope to show socialists that responding to the Anthropocene must be a central part of our program, theory, and activity in the twenty-first century, and to show Earth System scientists and environmentalists that ecological Marxism provides essential economic and social understanding that is missing in most discussions of the new epoch.

The book’s title has two meanings. It refers, first, to the fact that humanity in the twenty-first century faces radical changes in its physical environment—not just more pollution or warmer weather, but a crisis of the Earth System, caused by human activity. And it is a challenge to everyone who cares about humanity’s future to face up to the fact that survival in the Anthropocene requires radical social change, replacing fossil capitalism with an ecological civilization, ecosocialism.

The global environmental crisis is the most important issue of our time. Fighting to limit the damage caused by capitalism today will help lay the basis for socialism tomorrow, and even then, building socialism in Anthropocene conditions will involve challenges that no twentieth century socialist ever imagined. Understanding and preparing for those challenges must now be at the top of the socialist agenda.

Facing the Anthropocene is not the final word on any of these subjects. I do not have all the answers, and the task before us is immense, so please consider this as the beginning of a discussion, not a final declaration. I look forward to receiving responses, amplifications, and, of course, disagreements. The web journal I edit, climateandcapitalism.com, offers a forum for continuing discussion of the issues raised in this book.

The book is divided into three parts.

• Part One, A No-Analog State. In the past two decades, little noticed by mainstream media and most environmentalists, scientists have made critically important discoveries about the history and current state of our planet, and have concluded that Earth has entered a new and unprecedented state, an epoch they have named the Anthropocene.

• Part Two: Fossil Capitalism. Part One discussed the Anthropocene as a biophysical phenomenon, but to properly understand it, we must see it as a socio-ecological phenomenon, as a product of the rise of capitalism and its deep dependence on fossil fuels.

• Part Three: The Alternative. Another Anthropocene is possible, if the majority of humanity fights back. What should our objectives be, and what kind of movement do we need to achieve them?

Tucked away in the Appendix are two short essays on misunderstandings about the Anthropocene that have some currency on the left: the claim that Anthropocene science blames all humanity for the planetary crisis, and the related assertion that scientists have chosen an inappropriate name for the new epoch.

What This Book Doesn’t Do

Debate climate science. The science is unequivocal: greenhouse gas emissions, primarily resulting from burning fossil fuel and deforestation, have significantly increased Earth’s average temperature, and continue to do so. The only uncertainties concern how quickly and how high global temperatures will rise if nothing is done to slow or stop emissions. Anyone who denies that is either blind to the science, or deliberately lying: such people are unlikely to read this book, but if they do, they won’t be convinced.

Describe fully the planetary emergency. This book is about the discovery, effects, and socioeconomic causes of the Anthropocene, and that emphasis required omitting or limiting discussion of such vital issues as biodiversity loss and freshwater depletion. A large book could be written about each of the nine Planetary Boundaries that are at risk today and still the account would be incomplete. For readers who want to learn more, some suggestions for further reading are posted on climateandcapitalism.com.

The Truth Is Always Concrete

Much environmental writing reduces human history to population growth and technology change, both of which just happen somehow. Why some societies have higher birth rates than others, why the ancient Greeks only used steam power in toys, why the Industrial Revolution occurred in England and not India or China—such questions are not asked. Having defined a set of abstract ecological principles that apply to all societies at all times, any further explanation is superfluous.

Socialists are not immune to such reasoning. I have a shelf of books and pamphlets from various left-wing authors and groups, all proving that environmental destruction is caused by the accumulation of capital, and all jumping directly from that to a call for socialism. How are capitalism’s anti-ecological characteristics manifested concretely in the real world? Are today’s environmental crises simply new renditions of past problems, or is something new and different happening? If the latter, how should our strategies and tactics change? All too frequently, such issues are passed over in silence.

Even more disturbing, in the present context, are articles that criticize or reject the very concept of the Anthropocene, by left-wing authors whose first reaction to new science is to warn of potential political contamination from ideologically suspect scientists. It seems that for some, anything less than explicit anti-capitalism must be denounced as a dangerous diversion.

When Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859, Marx and Engels read it eagerly. They attended public lectures by prominent scientists whose political views were far from their own. Their private correspondence shows that they didn’t accept every word Darwin wrote, but they didn’t denounce him publicly for not being a socialist; rather, they did their utmost to incorporate the latest findings of science into their own work and world-view. Today’s anti-Anthropocene radicals should ask themselves, “WWMED?—What Would Marx and Engels Do?” What Marx and Engels would not do, we can be sure, is build walls between social and natural science.

Rather than carping from the sidelines about the scientists’ lack of social analysis (or worse, rejecting science altogether) socialists need to approach the Anthropocene project as an opportunity to unite an ecological Marxist analysis with the latest scientific research in a new synthesis—a socio-ecological account of the origins, nature, and direction of the current crisis. Moving toward such a synthesis is an essential part of developing a program and strategy for twenty-first-century socialism: if we do not understand what drives capitalism’s hell-bound train, we will not be able to stop it.

Nearly fifty years ago, the pioneering environmentalist Barry Commoner warned that “the environmental crisis reveals serious incompatibilities between the private enterprise system and the ecological base on which it depends.”2 It is now time—it is past time—to hear his warning and change that system.

Acknowledgments

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to John Bellamy Foster, editor of Monthly Review and prolific writer on Marxist ecology and economics. He provided frequent advice and gave me detailed comments and suggestions as my work proceeded, beginning when I proposed a short article on the Anthropocene. This book literally would not have been written without his constant support and encouragement.

Clive Hamilton, Robert Nixon, Peter Sale, Will Steffen, Philip Wright, and Jan Zalasiewicz took time from their work to respond to my emailed questions about their areas of expertise.

Jeff White carefully proofread several drafts, checked the reference notes and identified weaknesses in the text. Lis Angus, John Riddell and Fred Magdoff offered criticisms and insights that helped me to think the subject through and express my ideas more clearly.

The team at Monthly Review Press, Michael Yates, Martin Paddio, and Susie Day, have been a pleasure to work with. Erin Clermont copy-edited my final draft and prepared it for publication.

Parts of Facing the Anthropocene were previously published in Climate & Capitalism, Monthly Review, and other publications. All have been rewritten and updated for this book.

Many thanks to Drew Dellinger for permission to include a verse from “hieroglyphic stairway,” first published in the collection Love Letter to the Milky Way (White Cloud Press, 2011).

“System Change Not Climate Change” in chapter 12 was written by Terry Townsend for Green Left Weekly in 2007. Terry, who edits the indispensable Links Journal of International Socialist Renewal, kindly granted permission to publish an updated version here.

“The Fertilizer Footprint” in chapter 10 was first published in September 2015 by the nonprofit organization GRAIN, which makes its excellent materials freely available, without copyright.

Third printing, 2018: The description of the Carbon Cycle, on pages 123–4, has been revised.

Metric Measures

All scientific research uses the International System of Units (SI), commonly called the metric system, and this book follows that standard. Temperatures are given in degrees Celsius (°C). One degree Celsius equals 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit, so restricting the global average temperature increase to 2°C means restricting it to 3.6°F. Distances are given in meters and kilometers. One meter equals 3.3 feet. One kilometer equals 0.6 miles. A tonne, sometimes called a metric ton, is 1,000 kilograms, just over 2,200 pounds.