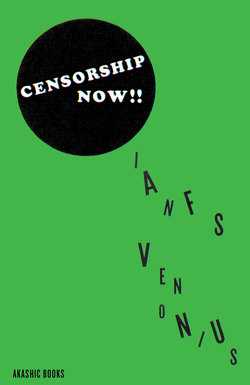

Читать книгу Censorship Now!! - Ian F. Svenonius - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

The Twist

The Sexual-Repression Revolution and the Craze to Be Shaved

SAM COOKE’S SONG “Twistin’ the Night Away” (1962) describes a scene where all ages, creeds, colors, ideologies, and class types are united in a utopian scene of unbridled excitement. An “older queen,” a “chick in slacks,” and “a man in evening clothes” all gyrate together in erotic abandon. They “lean back,” “fly,” and “Watusi” . . . but they never touch. Despite the optimism and joy of the tune, “Twistin’ . . .” actually promulgated a new world of utter individualism and isolation.

Sam Cooke’s song was one of many capitalizing on the dance megatrend initially announced on record by Cincinnati singer Hank Ballard and his group the Midnighters. Ballard’s “The Twist” (1959) was indeed the first completely alienated dance form. Instead of being part of a pair, line, couple, or group, twisters were dancers who were liberated from stifling community; they were individuals. The twist was a revolutionary force in breaking apart social units and enforcing individualist ideology. Though rock ’n’ roll music had existed long before this dance, the introduction of the twist was a shift which punctuated a profound new beginning for rock ’n’ roll: rock as a culturally enforced paradigm, which cut across race and class lines.

Before the twist was introduced, a night of dancing, even if it were a wild folk, blues, or jazz affair, featured people dancing with partners, sometimes many different partners. Oftentimes, they danced very closely to one another. A dance partner was someone who was felt, smelled, held, and who moved in tandem with their partner’s body. Sometimes there were dance cards issued so that dancers could reserve spots for various intended consorts. Emotional songs from the beginning of the rock ’n’ roll era implored lovers to “Save the Last Dance for Me.” The final cavorting of the night in the pretwist era, typically a slow and romantic number, was symbolic of the committed lovemaking of a partnership, as opposed to the evening’s countless other tawdry “quickies.”

With couples dancing, an orgiastic night of simulated fornication with multiple partners could be enjoyed by otherwise monogamous pairs who would lech the night away, their vows technically intact. Then the twist came in, permeating all social classes, propagandized into paradigmatic status with a hype campaign extraordinary even by contemporary psyop standards.

Pop envoys like Sam Cooke, the Isley Brothers, Gary U.S. Bonds, Petula Clark, Joey Dee, Chubby Checker, King Curtis, Bill Black, Jack Hammer, Cookie and the Cupcakes, Clay Cole, El Clod, Duane Eddy, Al & Nettie, Chris Kenner, Johnnie Morisette, Danny Peppermint, the Troubadour Kings, Rod McKuen, and countless others brought the good news to the masses. French singer Stella satirized the ubiquity of the sensation with her “Les Parents Twist” in which she sang: “How sad it is to have stupid parents doing the twist (while I try to sleep) / My mother has a fashionable haircut, it makes her look ridiculous / My father shouldn’t have bought a sports car, it’s hard to put all the family inside . . .” It took four years of incessant propaganda for the dance to completely infiltrate all sectors of Western society, with “twist” records reaching saturation levels in 1962.

After the twist came other dances: the fish, the frug, the horse, the cow, the swim, the camel walk, the James Brown, the pop-eye, the disco-phonic walk, the monkey, the gorilla, the kangaroo, the drive, the funky Broadway, the cat, the fish, the bird, the tighten-up, the sophisticated sissy, the Philly dog, the alligator, the twine, the Harlem shuffle, the Boston monkey, the shake, the shimmy, the shing-a-ling, the boo-ga-loo, the bounce, the freeze, the continental walk, the slide, the four corners, the fishing pole, the happy feet, the mohawk, the pass the hatchet, the mashed potatoes, the fly, the popcorn, the karate, the African twist, the barracuda, the beetle hop, the drive, the waddle, the duck, the ostrich, and a multitude of other crazes or would-be crazes ensured the dancer would always dance alone (the Madison, which debuted in 1957, was different in that it was a communitarian line dance, as was “the hully gully” popularized by the Olympics in 1959).

The dances were a milestone in culture. Many were reenactments of animal behavior, such as the monkey dance where the participant acted out primate pastimes such as the peeling of a banana. With “the bird,” the dancer flapped his or her imaginary wings. People were attempting to simulate wild beasts they had never seen or that were now scarce in an alienated, prefab world. In a sense, the dances were a funeral rite for a lost Garden of Eden.

With industrialization, humanity had realized its biblical prophecy and banished itself from the natural world, which it now only experienced through imperialist National Geographic documentaries. Food in the postwar period was, for the first time in recorded history, packaged without trace of its origins. Meanwhile, animals (except for a few domestic varieties) were unknown in the new suburban habitat. A few years before, pigs, chickens, and cows would have been visible within city limits, and butchers, fishmongers, and vegetable sellers would have plied their wares at markets. After World War II’s corporate consolidation, food became something that was shrink-wrapped, freeze-dried, or instant and boxed.

Dancers furiously tried to embody the animals they could no longer see, in an effort to call them back—to express either their admiration or their jealous contempt for them in a bittersweet goodbye. Dances like the twist and the tighten-up were ritualized reenactments of industrial machines used in factory work. These were also vanishing in the new economy based on consumerism, wherein people’s only skill and pastime would be to shop. All these moves were performed obediently following the barked dictates of a “lead singer,” who mimicked the behavior of the foreman on the factory floor or a galley slave driver.

The new, individualist dance crazes were so exhausting—as well as psychically and physically devastating—that they lasted only ten years (1959–1968). By 1969, dancing was all but forbidden by rock bands who insisted that their audiences sit obediently and consume drugs en masse whilst trapped in enormous arenas, raceways, pastures, and superdomes. The rebellion of narcotics had the appeal of being hermetic, secretive, and illegal, but their real purpose was escape from rock itself, which had become intolerable. Rock ’n’ roll’s alienation had defeated its victims who were now rendered exquisitely passive. Occasionally, the trend for regimented dance moves would reappear—either as camp (the disco fad’s “disco duck,” the “Bertha Butt Boogie,” and “the hustle”) or as satire (punk’s pogo, mosh, and slam)—but these attempts faded fast, impotently raging against the dying of the light. With the death of dancing, drug abuse became the rock fad, another step in the alienation of the music victim, lost in noise, buried in a stoned cacophony.

Before this, alongside the twist, oral contraceptives or “birth control pills” arrived, first marketed in 1960. The pill, though developed years earlier, had not made it to the marketplace, stymied by the FDA’s moral and health concerns. The twist forced the agency’s hand. Just as Adderall and Ritalin are part of a tool set required to navigate today’s cyber-Internet consciousness efficiently, and increasing loneliness and alienation engendered by cybersociety create the need for pills like Zoloft and Prozac, so was “the pill” a necessary invention in the newly twist-ed world. The new paradigm demanded it.

The pill is widely credited for launching the so-called sexual revolution and for sparking a new era of promiscuity and rebellion against the nuclear family unit and its oppressive gender roles. But the pill and the twist, along with other postindustrial dances, didn’t just encourage more sex without regard for pregnancy; they also parented a new relationship to sex. People engaged in intercourse with lots of different people not because they were newly carefree—there had been sex before this—but because dancing, the ancient ritualistic pantomime of intercourse and intimacy, was now an alienated action; an individualistic task where the participant was required to be alone, in a frenzied, masturbatory state, both highly stimulating and deeply depressing. The void was to be filled with actual fornication. The two phenomenon are therefore related: “The Twist” (1959) made the pill absolutely necessary, while “the pill” (1960) made the world engendered by the twist manageable.

Meanwhile, to dance now required working knowledge of new dance moves which—once the twist went sour—were always in flux. The discotheque was a place to announce one’s adroit command of moment-to-moment consumerism. Dances were like gadgets or jokes which showed off working knowledge of temporal ephemera, leisure time (a requirement so as to learn and practice the new moves), and buying power (so as to purchase the records which were necessary components for instruction). At the disco, when the latest 45 barked out the contortion of the week, the dancer was ordered to comply with the locomotion, the turkey trot, the whatchamacallit, the choo-choo, the bump, the lion hunt, the “after the fox,” the shotgun, the shake ’n’ bump, the funky walk, the wash, the sophisticated boom-boom, the monster walk, the lurch, the stereo freeze, the moonwalk, the broken hip, the bounce, the weirdo wiggle, the squiggle, the Tennessee wig walk, or the pimp walk. One’s dance partners were nonexistent or incidental; specters and shadows gyrating in the flashing half-light of the dance hall, hallucinations in the night. Sexual consorts were similarly identityless.

Sex itself was likewise extracted from what it had been—eternal and universal—and became a consumer’s whim, a new move; i.e., “fashion.” It was necessary for the rock ’n’ roller to engage in actual sex because of the lack of tenderness; touching one another casually had been made verboten by the new dances. Therefore, the conceit of the sexual revolutionary wasn’t only that those involved were having more sex but also that they had liberated sex entirely from its olden-days gulag of repressed courtship rituals and “teasing.” A spate of tease songs (Cliff Richard’s “Please Don’t Tease,” the Monteras’s “You’re a Tease,” Bob Kuban’s “The Teaser”) appeared in the early sixties, bullying diatribes against “Little Sally Tease” (Don & the Goodtimes) and other women who weren’t complying with the new era of mechanistic sex on demand.

Sex, during this so-called sexual revolution, was itself reinvented. Rock ’n’ roll’s stance has always been that it invented sex; that Elvis’s shaking hips were somehow a revelation to all those who saw them, something altogether new. And they were. They were rejecting the sex of the past—the Lost Generation sluts and sleazeballs who cavorted, canoodled, and contorted with people like Fatty Arbuckle—to create something entirely different. Sex was redefined. It was an ultraindividualistic sport of play and pantomime which didn’t even happen when it happened. Eros, once risqué, naughty, and discreet, became stark, narcissistic, and codified like the new dances; people practiced their moves, first through smut, then with post-hippie how-to manuals (such as The Joy of Sex), and then finally with “hardcore” pornography as a guide.

Pussy-eating, cocksucking, anal sex, threesomes, wheelbarrowing, and 69 were outlined, streamlined, diagrammed, and stripped of mystery. The cobwebs were cleared and a tungsten bulb was blasted at the newly clinical sex act. Without risk of pregnancy and with the new brutal aerobics of the frug and the jerk banishing intimacy, closeness, and tenderness, the teen-amphetamined world of rock ’n’ roll begat a whole new scene. This started with the guttural obscenities of the first rock ’n’ rollers. But though Elvis and other first wavers’ gestural feats led the way, the twist was the coup de grâce which finally did away with the sexual tenderness of the old world.

New razor technology was also introduced in the new age, to address the compulsory youthfulness enforced by the new adolescent rock ’n’ roll class. Formerly, “countercultures” sought wisdom and experience. The Beat Generation had wanted to look mature and rugged, while the Lost Generation were likewise scruffy adults. Now, people shaved whatever facial hair they had to maintain a young look. Not coincidentally perhaps, shaving technology became quite sophisticated in 1957—immediately before the twist appeared—with Gillette marketing the first “adjustable” razor, which allowed a closer cut than ever before. Yet all this shaving had another function as well: to enforce insensitivity, militarism, and a brutal machinist ideology.

Hair acts as antennae on the body. Hair on one’s body makes one sensitive to one’s environment. Religious people are typically hairy and resolve not to cut their hair lest their relationship with God—via their antennae—be severed. Hasidim, Amish, Rastafarians, Orthodox Muslims, and Sikhs all have edicts about maintaining certain hairs or hair that is sacred. Samson was the biblical story of a hero who lost his power by cutting his hair. Conversely, when the Greeks and Romans successively conquered their respective known worlds, they were remarkable for their decision, culturally, to be without facial hair. Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, a Greek descendant, was the last of the kings of Rome (535–496 BC) before the Senate era, and also the man to introduce the razor to the kingdom.

Lucius shaving himself signaled a paradigm shift which brought about his own defeat. The beard was a signal of the monarchic father authority, while the shaved face was androgynous and democratic. The razor excited new passions which struck with a dialectic fist. Shaving reversed time and blurred identity. Old could suddenly be young, masculine could be feminine, identities were revealed to be mutable/equivocal, and a craze for democracy was the result. Lucius’s dynasty was overthrown and gave way to the senatorial Rome of historic renown. After he was deposed, the newly shaven Roman Republic was declared, which then set about conquering the known world.

The Romans had taken their democratic model from the Greeks of Athens, who had also been known to shave and oil their bodies, as had the Egyptians who inspired them. In antiquity, the Athenians maintained an empire in the Peloponnese, demanding slaves and treasure from their neighbors. The Romans eclipsed Greek conquests and have been the aesthetic template for most imperial projects since, e.g., the National Socialists, Bismark’s Prussia, the European fascist movements of the 1930s, Napoleon (whose reign was synonymous with the architectural “Empire” style), Great Britain, and the USA (Washington, DC’s neoclassical buildings, the eagle as national symbol, and the “fasces” wall adornment at the US Congress are but a few examples of the country’s repetitive and unimaginative invocations of Roman imperial power).

Our sexual ideas are also borrowed not from the sophisticate cultures who created the Kama Sutra, but from kindred brutalists, the Romans. Roman depictions of sex in the ubiquitous brothels of Pompeii, which feature Priapus centrally, are curiously similar to images of modern pornography.

Hairless tribes were dominant over their hairy neighbors. Besides haircutting, rituals of self-mutilation were symbols of tribal potency; circumcision, an obvious example, was not religious but a cultural designator of toughness and exclusivity. In parts of the world with more history, such as Asia, it’s theorized that relative hairlessness developed as an evolutionary trait of survival. As the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians showed, less hair meant military prowess and dominance over foes. Hairiness was a sacred trait, reserved for the noncombatants such as holy men, poets, philosophers, crazies, and nursing mothers. Similarly, shaving one’s body desensitizes ones body. It makes one more machine-like, more macho; it makes brutality easier. As soon as hairiness was associated with leftism, the fate of that ideological propensity was doomed.

With the so-called sexual revolution, people started shaving not only their faces but also their pubic regions. This began with an avant-garde of homosexuals but spread with the popularization of pornography via the Internet and the “hook-up culture” of casual straight sex performed by nerds and squares. The shaved body signals a person who’s not hung up by attachments, feelings, romanticism, or any of the tawdry aspects of relationships or “love.” The shaved crotch was one that was ready for wordless action steeled against vulnerability.

Onlookers of porn complain of the childlike resemblance of the shorn genitals, that the shaved vagina looks prepubescent, which makes them uncomfortable. But the shaved pubic area is meant to look preadolescent. It denotes a preadolescent disregard for the potency of sex in regard to emotionalism, romanticism, etc. Pubic hair paradoxically doesn’t protect the sex organ but extends it; it is a quite sensitive part of it.

Chopping off one’s pubic hair is akin to cutting the foreskin or female genital mutilation that persists in some parts of the world. It is designed to desensitize. Violence-worshipping youth cults such as the military and the “skinheads” of Britain typically shave their heads as a designation of sociopathic unfeeling. The hair, instead of protecting or hiding the organ, actually comprises thousands of feelers which lend sensitivity to the organ, exposing it to its partner’s signals of empathy, love, lust, shame, fear, disgust, et al. A hairy body is simply less prepared for modernistic, mechanized body-mashing.

Hairlessness is an aggressive stance, and implies a lack of vanity and disdain for luxury. It implies a state of war. A French-style waxing job or pubic “landing strip” is like the so-called mohawk haircut favored by the Pawnee tribe and used in times of war by Cossacks, airborne troops, and the like. The “Brazilian” wax job is the full skinhead.

In the pretwist era, the dancer would often dance with many partners in a simulated orgy. It was essentially a tryout for sex or a replacement, but in its explicitness and its intimacy, it could not be called repressed. After the twist was introduced, sex repression saw its apex expression in the “mania” or alienated and displaced erotic cavalcade which met the Beatles and other stars of the era. After the disappointment engendered by the Beatles’ breakup came a mass, culturewide depression. Soon afterward, drug abuse became practically compulsory for teens who liked music. This was another replacement for sex. The so-called sexual revolution, celebrated as a liberation which encouraged participants to have more sex with more partners, was actually a revolutionary transformation of sex: changing what had been the sex act into a series of alienated, self-conscious moves, or replacing it with the sensual high of the institutionalized “culture” of drugs.