Читать книгу Clydebank Battlecruisers - Ian Johnston - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

During the period 1906 to 1916, five main classes of battlecruisers were built for the Royal Navy, a total of thirteen ships. The orders for these vessels were distributed across the principal shipyards, Royal Dockyards and private yards responsible for all the capital ships built up to and including the First World War. For many of these yards, this meant an all but continuous supply of prestigious contracts, particularly so in the case of battlecruisers which were generally of a higher order value than their battleship equivalents and moreover, held in very high esteem by the Navy and public alike in the years up to 1914.

The very rapid development of the battlecruiser type during the ten-year period from 1906 to 1916 resulted in ships half as long again on twice the displacement, 20 per cent faster and with 50 per cent more offensive power. Naturally, the increase in size that inevitably accompanied successive classes of capital ship had an impact on the yards that produced them to the extent that, by 1916, only a handful of the yards that started building the early dreadnoughts were capable of building ships the size of Repulse and Hood.

The John Brown shipyard and marine engineering works on the River Clyde is significant in the construction of battlecruisers for two reasons. The first is that the records of this company have survived the collapse of the British shipbuilding industry substantially intact although with some important areas missing. In this, John Brown’s is probably better served historically than any of the other big British yards operating at that time. These records provide access to information about the construction of the ships they built in the form of a detailed breakdown of costs and the labour devoted to each contract. The latter, expressed in weekly levels, gives an indication of effort over the entire building period. However, the skills and techniques employed at Clydebank were much the same as those in any of the big British yards and to that extent, the experience of Clydebank can be seen as typical of the rest of the industry as a whole. Secondly, John Brown’s is noteworthy in having built one battlecruiser from each of the five main classes beginning with Inflexible followed by Australia, Tiger, Repulse and Hood. Had the construction of the ‘G3’ battlecruiser design of 1921 gone ahead, Brown’s would also have contributed one of those.

While there are many expert books on the design history and operational careers of battlecruisers, the purpose of this book is to look exclusively at the construction of the five that were laid down over a ten-year period at Clydebank. The working practices, machines and tools used there were typical of those used throughout the shipbuilding industry and to that extent, the events described here could as easily have taken place at any of the other large British yards. While the shipyard was the point of assembly, the ramifications of building such large and complex vessels ran through much of British industry, with companies located throughout the UK making contributions to the ship as disparate as barbette armour and the ship’s bell.

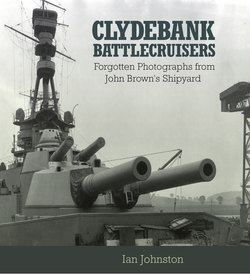

The river frontage of John Brown’s Clydebank shipyard in 1907. The Cunard liner Lusitania is in the fitting-out basin which separates the works into West and East Yards. While there are no vessels under construction in the West Yard, the East Yard is well occupied. The shipbuilding berths are served by light pole derricks capable of lifting three tons. The stern of Inflexible can be seen to right of shot. See yard plan overleaf. (Author’s collection)

The sequence of events from conception of the design of a warship, through the tendering process to the construction, completion and trials is largely the same for all the vessels described here. The information used to describe this process is based on two sources: the Ships’ Covers held at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and the archives of John Brown & Co Ltd, Clydebank, held at Glasgow University Archives. The Ships’ Covers were used to retain documents relevant to individual ships from the conceptual phase through construction and subsequent service careers. They reflect Admiralty thinking through internal memos, letters, reports and other material across a range of subjects pertinent to a particular ship or class of ships. The shipbuilder’s records are concerned exclusively with the tendering and construction phases of the ship. Together, both sources throw some light on the relationship between the Admiralty and the shipbuilding firms in what has generally been a neglected area of study. The Covers are, however, somewhat haphazard in their organisation with some documents out of chronological order and others undated. Where the Cover for one ship might give a full report on steam trials, for example, this might be missing entirely in another. The John Brown archive, although voluminous, is also incomplete and inconsistent in part. For those reasons, an even treatment of the five ships that concern this book is not possible. However, a particular strength of the John Brown Archive is the large number of glass plate negatives which record the building process from keel laying to trials. These excellent images provide the pictorial basis for this book.

John Brown & Co Ltd

By the time Inflexible was laid down at their Clydebank shipyard in 1906, the yard had been in existence since 1871. Many prestigious liners had been constructed over the years and a lasting relationship had been formed with Cunard, the most recent example of which was the order for Lusitania. However, the Clydebank works did not assume the title John Brown & Co Ltd until 1899 when the Sheffield company of that name purchased the yard for a little under £1 million. The Sheffield company wanted a secure outlet for their steel forge and armour products and correctly foresaw a great opportunity in warship construction not simply because of the Royal Navy’s pre-eminent position in the fleets of the world but also in the emerging naval race between Britain and Germany. During the 1890s a number of well-known British companies with armour and armament manufacturing capacities had also ventured into shipbuilding, such as Vickers at Barrow and Cammell at Birkenhead, as a means of extending and consolidating output. In all probability, the reality of this contest as measured by the volume of warship orders that ensued exceeded their wildest dreams.

Even before the acquisition of Clydebank by John Brown, the yard had completed an interesting number of warship orders. From the mid-1880s, onwards, a series of small cruisers were built for the Admiralty as well as a protected cruiser for the Spanish (Reina Regente) and Japanese (Chiyoda) navies. More orders followed for larger vessels including Terrible (1897) and many torpedo-boat destroyers. The first battleship order was Ramillies (1892), followed by Jupiter (1895), Asahi (1899) for the Japanese government and Hindustan (1903). Under the ownership of John Brown & Co Ltd, the Clydebank Works had a high degree of autonomy although major decision making was referred to the main John Brown Board, under the chairmanship of Lord Aberconway, which met at either the Sheffield Works or at the company’s London offices at The Sanctuary.

By 1906, the Clydebank Works covered 80 acres comprising two yards separated by a fitting-out basin and a large engine and boiler works. The town of Clydebank grew up around the shipyard which by 1899 had a population of 19,000. By 1906, the Clydebank Works was well equipped, highly efficient and an experienced shipbuilding and marine engineering facility employing up to 10,000 workers.

Sir Thomas Bell

The Managing Director of the John Brown works at Clydebank was Thomas Bell, knighted in 1918 for his services to the nation as Deputy Controller of Dockyards and War Shipbuilding for the period 1917–19. Bell was a marine engineer and responsible for the introduction of the Brown Curtis turbine to Clydebank. This turbine found favour with the Admiralty and was used in propelling Tiger, Repulse and Hood as well as many other warships. Bell attributed the success of his firm in winning these orders to that turbine. In 1919, on his return as Managing Director of the Clydebank works, he said that ‘Clydebank stood in the Admiralty records easy first, not alone for excellence of work but what was at that time of still greater importance, absolute fidelity to their promises of dates of delivery.’

The Naval Construction Industry

Britain’s pre-eminent position in the fleets of the world, both naval and mercantile, ensured a very large shipbuilding industry. While the Royal Dockyards had traditionally built the ships the Royal Navy required, increasingly the private shipyards were participating in warship building programmes. The Admiralty nurtured these firms by ensuring sufficient orders were distributed across the industry. To be eligible to build warships, a builder had to be on the Admiralty List. This required that a shipbuilder had the requisite experience and suitable plant and facilities for any given class of warship or equivalent experience in mercantile work. Constructing the battle fleet that went to sea in the First World War, required the resources of a large portion of the private shipbuilding industry in addition to the Royal Dockyards. The following firms in addition to Portsmouth and Devonport Dockyards, participated in the construction of battlecruisers and battleships from 1906 onwards.

(Drawing by the author)

A midships view taken on 13 July 1916 of Repulse with two ‘R’ class destroyers fitting out alongside. Painting is underway on the forward superstructure including bridge, tripod foremast and fore funnel. The spotting top of the monitor Erebus, brought to Clydebank to have her 15in mounting fitted can be seen bottom left.

(NRS UCS1-118-443-275)

In this 1918 view from the stern of a river steamer, the 150-ton cantilever fitting-out crane dominates the skyline with the East Yard behind. Reflecting the heavier loads being lifted, the shipbuilding berths have now been equipped with steel lattice derricks capable of lifting five tons. (Imperial War Museum Q19400)

Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick and Walker (no associated engine or boiler works)

Beardmore, Dalmuir

John Brown, Clydebank

Cammell Laird, Birkenhead

Fairfield, Govan

Palmers, Jarrow

Scotts, Greenock

Thames Iron Works, Blackwall

Vickers Son & Maxim, Barrow in Furness

Other major shipbuilders such as Harland & Wolff and Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson, who were on the Admiralty List, either declined to tender or were unsuccessful in winning contracts.

While the shipyards brought ships into existence, vital parts of the ship such as armour and armament were manufactured elsewhere and transported by rail or sea to the shipyard concerned. There were five large armour-rolling mills in Britain at the time of the First World War but only three firms capable of manufacturing heavy gun mountings. The same applied to the construction of main propelling machinery. While most of the large shipbuilding firms mentioned here had integrated or associated engine and boiler works, some did not. Where a warship contract was awarded to a shipbuilder without an engine works, it was the shipyard’s responsibility to sub-contact this work to an engine works acceptable to the Admiralty. The Royal Dockyards relied on private firms for the manufacture of engines and boilers and, for example, when the contract to build the battlecruiser Indefatigable was given to Devonport Dockyard, the machinery contract was won by John Brown at Clydebank.

The Coventry Ordnance Works (Coventry Syndicate)

Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers Son & Maxim effectively cornered the market for the design and manufacture of heavy gun mountings, highly complex and time-consuming mechanisms to construct. This conferred a distinct advantage to these firms when tendering for warship contracts. In an attempt to break this monopoly, John Brown, Cammell Laird and Fairfield developed the Coventry Ordnance Works from 1905 with the capacity to design and construct guns and mountings. The Works comprised an ordnance factory at Coventry where mountings were designed and guns manufactured. A new ordnance works was built at Scotstoun, on the Clyde where mountings were assembled and tested in gun pits from where they would be taken by barge or ship to the shipyards.

Hundreds of other firms were involved in the supply or manufacture of materials and products for HM ships. Together, the industry that produced warships in Britain was a very large one that in the years before and during the First World War accounted for a significant portion of the public purse. The decade and a half prior to 1914 was dominated by intense naval rivalry between Britain and Germany, which had begun in 1897 when the German legislature passed the first of Admiral Tirpitz’s Naval Laws. These, in effect, committed Germany to building a fleet to rival the British. While this initially seemed an impossible target to meet, the British battlefleet was made obsolete by the British themselves with the introduction of the all-big-gun battleship Dreadnought in 1906. This ship outclassed all preceding classes of battleship, and, in effect, reduced the Royal Navy’s lead in modern battleships to just one. Germany, with a formidable industrial base of its own, thus had the opportunity to keep pace with British construction. Against this background, a ‘naval race’ ensued between Britain and Germany, a trial of industrial strength as much as political will in which British resolve, resources and shipbuilding capacity won the day.

PRINCIPAL ARMOUR AND ARMAMENT COMPANIES:

| Armstrong Ordnance: | Elswick Works, Newcastle |

| Armour and Forgings: | Openshaw Works, Manchester |

| Gun Mountings: | Elswick Works, Newcastle |

| Vickers Ordnance: | River Don Works, Sheffield |

| Armour and Forgings: | River Don Works, Sheffield |

| Gun Mountings: | Barrow |

| Beardmore Ordnance: | Parkhead Works, Glasgow |

| Armour and Forgings: | Parkhead Works, Glasgow |

| John Brown Armour and Forgings: | Atlas Works, Sheffield |

| Cammell Laird Armour and Forgings: | Grimethorp Works, and Cyclops Works, Sheffield |

The Photographs

Like many shipbuilding firms, John Brown & Co used photography to record the construction of vessels, usually starting with keel laying and ending with trials. The ship’s machinery, engines and boilers were also recorded. To do this, a photographic department was established at Clydebank employing up to five photographers and darkroom personnel. As this was an expensive overhead, many other shipbuilders opted to employ outside commercial firms to take progress shots as and when needed. The photographs tended to follow a similar pattern from ship to ship and established a clear record of progress at a given date. Although there was obvious interest in recording the construction of ships at Clydebank, many of which were large and prestigious, the exact purpose of the photographs is unclear. There is no evidence that they were routinely sent to ship owners and certainly no reference to them at all in correspondence with the Admiralty. Neither are they specified as a necessary part of the contract.

Presentation volumes showing the ship in various stages of construction were often given to owners on the completion of the ships, including the Admiralty. Beyond this thoughtful gesture, the photographs appear to have been for company purposes only and were often used by John Brown & Co in publicity materials and engineering articles.

That this photographic collection has survived at all the decimation that has taken place across British industry is remarkable in itself and has resulted in the preservation of one of the finest records of ship construction in modern industrial Britain. Throughout the period covered by this book, photographic exposures were made on glass plate negatives measuring 10 × 12in and occasionally on plates of 12 × 15in. The cameras used were necessarily large, and together with substantial tripods, made for a cumbersome and heavy load to be carried across the large area of a shipyard. Setting up to make an exposure was a time consuming event not to mention a hazardous and often high-wire activity given the need to climb cranes or scale hulls in various stages of completion in a dangerous working environment. Slow emulsions required time exposures which account for the sometimes blurred appearance of men working but compensated by allowing for images of exceptional detail. The growing use of photography at Clydebank can be seen in the number of exposures made for the five ships that make up this book: around sixty negatives were exposed covering the construction of Inflexible, rising to over 600 for Hood.

The first three ships, Inflexible, Australia and Tiger, were built under peacetime conditions where the due and lengthy process of tendering applied and no undue pressure was made on the shipbuilder during construction. This was in stark contrast to the urgency of wartime conditions where events moved much more quickly. So fast in fact, that in the case of Repulse, the shipbuilder was commanded to start work more or less right away with little by way of preparations, specifications or drawings to guide the way. On his retirement from John Brown’s in 1946, Sir Thomas Bell recalled the meeting that he and Alexander Gracie of Fairfield’s had with Lord Fisher at Christmas 1915 in order to impress on them the urgency of building Repulse and Renown rapidly and quoting him as saying ‘I am going to have these ships delivered on time and if you fail me your houses will be made a dunghill and you and your wives liquidated’, adding ‘I expect to hear tomorrow that you have started preparations for these ships.’ The environment in which Hood was constructed was completely different again, subject to delay through partial redesign in the wake of the battle of Jutland and then encountering an acute shortage of labour within a shipbuilding industry that was working to capacity.

The John Brown photographs of the five battlecruisers covered by this book offer an insight into this unparalleled period of industrial endeavour particularly when it is considered that a total of fifty-one capital ships were built in British yards from Dreadnought in 1906 to the completion of Hood in 1920.

Another feature of these photographs is the depiction of the ships ‘as built’, with the overall balance of the design as the naval architect or constructor originally intended, unadorned by service or wartime additions. The ‘as built’ ship provides an interesting alternative to popular images and models of warships that favour late configurations which often depict ships after years of modifications and additions with the invariable accumulation of often ungainly clutter.

Note that the NRS photo reference numbers, where applicable, are given at the end of the captions.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following persons for help in the preparation of this work: Ian Buxton and Brian Newman for reading the manuscript and Ian Sturton for kindly allowing me to use some information he uncovered in researching Hood’s unbuilt sisters. I am indebted to the following institutions for their help in accessing their archives:

National Maritime Museum

Historic Photographs and Ship Plans Section, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Jeremy Michel and Andrew Choong.

Glasgow University Archive Services

The Customer Services Team

National Records of Scotland

Image Library:

Matthew Fawcett, Leanne Jobling, Gill Mapstone, John Simmons, Pat Todd

Conservators:

Eva Martinez Moya, Linda Ramsay

Digital Services:

Paul Riley

A debt of thanks is also due to Rob Gardiner at Seaforth for his enthusiasm and assistance and to Stephen Dent for the design of this book.

Ian Johnston,

March 2011