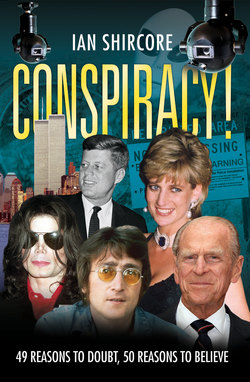

Читать книгу Conspiracy! 49 Reasons to Doubt, 50 Reasons to Believe - Ian Shircore - Страница 27

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление— SECOND YORKSHIRE RIPPER —

COULD THERE HAVE BEEN MORE THAN ONE?

Even those who were not alive in the late 1970s have heard of the Yorkshire Ripper, the cruel and elusive murderer who killed time after time and baffled some of Britain’s finest detectives for more than five years.

When lorry driver Peter Sutcliffe was finally arrested in January 1981, the nation heaved a sigh of relief. Altogether, there had been at least 13 murders – mainly of sex-trade workers in the West Yorkshire area – plus a number of vicious attacks on other women.

Sutcliffe was a violent, brutal paranoid schizophrenic, though he was deemed to be sane enough to stand trial. He attacked his victims with ball-peen hammers, knives and sharpened screwdrivers, killing and mutilating them because, he claimed later, he heard voices in his head telling him to kill prostitutes. The voices, he said, were the voice of God, and the former gravedigger claimed to believe they came to him from the headstone of a long-dead Polish immigrant.

Sutcliffe confessed and was tried on 13 charges of murder and seven of attempted murder. He was found guilty on all the charges and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Because he was held to be sane, Sutcliffe was sent to an ordinary prison to serve his life sentence. He was seriously assaulted by another prisoner and soon reassessed and sent to the secure psychiatric hospital at Broadmoor. In 2010, after a legal application that could have opened up the possibility of parole had been turned down, he was told he would be spending the rest of his life in Broadmoor.

No one doubts that Peter Sutcliffe was rightly found guilty of committing a string of horrific murders. But did the numbers add up?

There were rumours that Sutcliffe knew the gruesome details of some of the murders, but couldn’t say anything at all about some of the others. And there were claims that the forensic evidence clearly pointed to two different killers.

Thirty years on, the questions remain. Were there two Yorkshire Rippers? And did the police, anxious to clear up a long-running, high profile case, conspire to cover up the facts, even though it meant a ruthless serial killer was still at large?

During the years before Sutcliffe’s arrest, the man leading the hunt, Assistant Chief Constable George Oldfield of West Yorkshire Police, had been taunted and teased by messages that claimed to be from the Yorkshire Ripper. These were taken seriously, as they seemed to include unpublished details only the killer could know, and they served to confuse the investigation. One message was on a cassette tape and the voice was quickly identified as having a distinctive Wearside accent, pinpointed as coming from the Castleton area of Sunderland. Sutcliffe was 80 miles away and spoke very differently. While the police followed up the Wearside connection, Sutcliffe went on killing.

In 2006, more than a quarter of a century later, an unemployed alcoholic called John Humble was convicted of perverting the course of justice, after a cold-case review had done some clever DNA matching with a saliva trace from one of the original envelopes. Humble was from Sunderland, within a mile of Castleton.

That finally dealt with the mystery of the Wearside Jack tape. But the bigger questions about the Yorkshire Ripper case still won’t go away.

REASONS TO DOUBT

There is one very simple reason to believe that, whatever the apparent inconsistencies, the police got it right.

The murders stopped, as far as we know, when Peter Sutcliffe was arrested, convicted and jailed. That isn’t conclusive proof, of course. If there was a second Yorkshire Ripper and he had been deliberately exploiting Sutcliffe’s murderous activities as a distraction and cover for his own crimes, you might expect that those would come to an end, too – assuming the second murderer was able to stop himself from killing again.

From a public safety point of view, the fact that the murders ceased was obviously a welcome development. But the ending of the long sequence of killings of prostitutes and other women in West Yorkshire didn’t necessarily mean there was no longer a murderer to be brought to justice.

REASONS TO BELIEVE

For the suspicious and the sceptical, the whole Yorkshire Ripper case has never been successfully solved.

Many of the witnesses and most of those who took part in the investigation are long dead. But one person who was deeply involved was Ron Warren, who was deputy chairman of the West Yorkshire Police Authority at the time of Sutcliffe’s arrest. He never had any doubt that there were important aspects of the 13 murders that were concealed from the public and the legal system.

‘There were definitely two murderers involved in the thirteen,’ Warren told the Yorkshire Post in 2005. ‘It was well known in the operations room that there had to be two, because of the blood evidence. I do believe Sutcliffe was found guilty of more murders than he could possibly have committed.

‘I suppose the police were more interested in getting it all wrapped up than in getting at the whole truth.’

Even more recently, at the age of 89, Warren was asked if the police had really been aware that Sutcliffe was not the only killer (see bit.ly/ripperblood).

‘All the police knew there were two men involved,’ he said. ‘It was fairly obvious from the forensic evidence that there were two, because there were two different blood groups involved.’

There has been an argument for many years about Peter Sutcliffe’s blood type. The police stated he was blood type B, while others have claimed that his father insisted it was type O, which might seem to be supported by Warren’s comment.

But this issue is not as critical as it might seem. Physical evidence from several of the Ripper murders pointed to a killer who was not just type B, but a B secretor. This means that the B antigens are secreted and show up in body fluids. Those who stated Sutcliffe was type B also said that he was a non-secretor, which would mean that the body fluids found at the crime scenes were not from him. Whether he was identified as a type B non-secretor or as a type O, either way he could not be linked to those particular murders.

And, since there is no way of changing or disguising your blood group, that is decisive, damning evidence that there were two killers, two Yorkshire Rippers.

In fact, not long before Sutcliffe’s arrest and confession, George Oldfield, the man leading the police inquiry, was quoted by Sunday Times journalists as conceding the point: ‘There is not one Ripper, but at least two.’

No one doubts that Peter Sutcliffe committed at least some of the murders. But it took a long time for even that to be established.

Between November 1977 and February 1980, Peter Sutcliffe was interviewed and eliminated from police enquiries nine times. Over and over again, enquiries about his cars, his movements, sightings of his vehicles in the red-light districts – even about a new £5 note from his pay packet that was found in the handbag of one of his early victims – were apparently contradicted by alibis or because his accent and handwriting did not match the messages from the Sunderland hoaxer.

One bright policeman, Detective Constable Andrew Laptew, had a strong hunch that there was something not quite right about Sutcliffe. DC Laptew and his colleague DC Graham Greenwood didn’t know Sutcliffe had already been questioned about the £5 note. But, as they interviewed him, they realised that he fitted almost everything the police knew about the man they were looking for. He was the right height and build, with dark hair and complexion, a beard and a walrus moustache. He had small feet and the odd gap between his front teeth that one of the attack victims had mentioned. He also worked as a lorry driver.

If Laptew had talked to Sutcliffe’s workmates, he’d have found out his topical, ironic nickname. With his dark, brooding presence, they called him ‘The Ripper’.

‘He stuck in my mind,’ Laptew said. ‘He was the best I had seen so far and I had seen hundreds. The gap in his teeth struck me as significant. He fitted the frame and could not really be taken out of it.’

This was the fifth interview with Sutcliffe. When Laptew followed up afterwards and found Peter Sutcliffe was one of the possible recipients of the telltale £5 note, he wrote an urgent two-page report, recommending Sutcliffe should be re-interviewed by senior detectives. The report was passed on, left in a pile, considered and dismissed nine months later and eventually marked ‘to file’.

The police have always avoided going into too much detail about how and why they repeatedly eliminated Sutcliffe from the investigation. But the answer is straightforward. He was ruled out, time after time, because he didn’t appear to fit the evidence. Despite all the witness descriptions and evidence about £5 notes, vehicles, tyre tracks and boot prints that could have incriminated him, his alibis, mainly provided by his wife, seemed to put him in the clear.

And, of course, if you accept the forensic evidence that there were two Yorkshire Rippers at work, it’s not surprising that the clues didn’t all point the same way.

By early 1981, the pressure on the police to get a result was almost intolerable. The build-up of public anxiety and negative publicity over more than five years of failure blighted the careers of all the senior officers involved. After Peter Sutcliffe was finally arrested in Sheffield – for having false number plates on his car – it was a huge relief to West Yorkshire Police when Detective Superintendent Dick Holland persuaded him to confess to all 13 murders.

Holland, it later turned out, had form. He was the officer who had suppressed forensic evidence five years earlier leading to Stefan Kiszko’s wrongful conviction for the murder of 11-year-old Lesley Molseed. Kiszko spent 16 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit and died a year after being released.

There has been no serious legal attempt to establish the identity of the second Yorkshire Ripper, despite occasional complaints by some relatives of the murder victims, who have become increasingly convinced that there was a cover-up.

At present, no one knows whether the second killer, who was presumably a good deal smarter than Sutcliffe, actually ended his murderous career or carried on killing in less obviously connected ways and places. There is one extraordinary, impassioned and controversial book, The Real Yorkshire Ripper, by Noel O’Gara, that denounces the whole conspiracy of silence and names the man O’Gara believes was the killer who got away with it. O’Gara says this man was the ‘real’ Yorkshire Ripper and killed a total of ten women, while Sutcliffe was a copycat, used and manipulated by the first killer and only responsible for four deaths.

Others have given up on trying to do the criminal detective work but still hope for answers about why the police were allowed to pretend Peter Sutcliffe’s conviction tied up all the loose ends.

The conspiracy to declare the case closed, in defiance of the evidence and only a matter of months after detectives were telling national newspaper reporters there were two Yorkshire Rippers on the loose, still leaves a nasty taste. And there must be big questions about how high the tentacles of such a cover-up would reach.