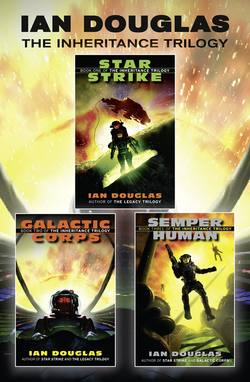

Читать книгу The Complete Inheritance Trilogy: Star Strike, Galactic Corps, Semper Human - Ian Douglas, Matthew Taylor - Страница 52

Platoon Commander’s Office UCS Samar Dock 27, Earth Ring 7 0910 hrs GMT

Оглавление“What the hell were you thinking, Marines?” Either Lieutenant Kaia Jones was furious, or she was one hell of an actress. The muscles were standing out like steel rods up the sides of her neck, and the anger behind her words could have melted through Type VII hull composite. “Switching off your AI contacts like that?” She paused, sweeping the six Marines standing in front of her desk with a gaze like a gigawatt combat laser. “Well?”

“Sir, we were not thinking, sir!” Ramsey snapped back, his reply militarily crisp.

“No, I should think the hell you weren’t.”

The six of them stood at attention in Jones’ office on board the Samar. After an uncomfortable night in the SP brig ashore, they’d been escorted back to the ship by a pair of square-jawed Navy petty officers with no-nonsense attitudes and little to say. Master Sergeant Adellen had met them at the quarterdeck, signed off on them, and ordered them to stay in the squad bay, except for meals, until they could see the Old Man.

“Old Man,” in this case, was a woman; long usage in the Corps retained certain elements of an ancient, long-past era when most Marines were male. The commanding officer was the Old Man no matter what his or her sex. Just as a superior officer was always sir, never ma’am.

Of course, the joke in Alpha Company was that in Jones’ case, you couldn’t really tell. She’d been a Marine for twenty-three years—fifteen of them as enlisted. She’d been a gunnery sergeant, like Ramsey, before applying for OCS and going maverick, and her face was hard and sharp-edged enough that she looked like she’d been a Marine forever.

Rumor had it that she’d been a DI at RTC Mars, and Ramsey was prepared to believe it.

“What about the rest of you?” Jones demanded. “Any of you have anything to say?”

“Sir …”

“Spit it out, Chu.”

“I mean, sir, everyone does it. If we didn’t have some privacy once in a while, we’d all go nuts!”

Jones leaned back in her chair and watched them for a moment, her gaze flicking from one to the next.

“Privacy to jack yourself on nanostims,” Jones said at last.

“Sir!” Gonzales looked shocked. “We would never—”

“Spare me, Gonzo,” Jones said, raising her hand. “You were all medscanned at the Shore Patrol HQ, and I’ve downloaded the reports. You were all buzzed. The wonder of it was that you were still able to stand up … much less incapacitate that group of … young civilians.”

“Sir, you … know about that, too?” Ramsey asked.

“Of course. Your little escapade was captured on three different mobile habcams, as well as through the EAs of two of your … targets the other night. As it happens, you single-handedly took out half of the hab’s local militia.”

“What?” Colver exclaimed. “Those punks? Sir! There’s no way!”

“Don’t give me that, Colver. You’ve been in the Corps long enough to know about gangcops.”

Ramsey digested this. He’d run into the practice at several liberty ports, but he’d not been expecting it at a high-tech, high-profile facility like Earth Ring 7. Gangcops and police militias were widely tolerated and accepted as a means of ensuring the safety of the larger cities and orbital habs.

It was the modern outgrowth of an old problem. Police enforcement could not be left entirely to AIs, neither practically nor, in most places, by the law. When local governments had problems recruiting a police force, they sometimes resorted to enlisting one or another of the youth gangs that continued to infest the more shadowy corners of most major population centers. The idea was to clean them up and give them a modicum of training—“rehabilitate them,” as the polite fiction had it—and send them out with limited-purview electronic assistants tagging along in their implants. Whatever they observed was transmitted to a central authority, usually an AI with limited judgment, keyword response protocols, and a link to city recorders that stored the data for use in later investigations or as evidence in criminal trials.

Defenders of the policy pointed out that crime in targeted areas did indeed tend to drop; its critics suggested that the drop was due less to crime than to less reporting of crime; paying criminals to act as police militias was, they said, nothing less than sanctioned and legalized corruption.

In any case, a certain amount of graft, of intimidation, even of violence was unofficially tolerated, so long as the peace was kept. Wherever humans congregated in large and closely packed numbers, there was the danger of panic and widespread violence. Political fragmentation, religious fanaticism, rumors about the Xul or about government conspiracies all spread too quickly and with too poisonous an effect when every citizen was jacked in to the electronic network designed to allow a near instantaneous transmission of information and ideas, especially within tightly knit and semi-isolated e-communities.

Most citizens accepted the minor threat of being hassled by street-punk militias if it meant the authorities could identify and squash a major threat to community peace quickly. The Earthring Riots of 2855—in Corps reckoning the year had been 1080, just twenty-two years before—were still far too fresh in the memories of too many, especially within the orbital habitats where a cracked seal or punctured pressure hull could wipe out an entire population in moments. The Riots had begun less than twenty hours after the appearance of a rumor to the effect that the Third and Fourth Ring food supplies had been contaminated by a Muzzie nanovirus. That rumor, as it turned out, had been false—a hoax perpetrated by an anti-Muzzie fundamentalist religious group—but over eight hundred had died when the main lock seals had been overridden and breached in the panic.

And so the authorities had begun cultivating various street gangs and civil militias, with the idea that the more people there were on the streets with reporting software in their heads, the sooner rumors like the one about a terrornanovirus one could be defused.

“Sir,” Ramsey said, “we didn’t know those … people were militia.”

“That’s right,” Delazlo added. “They came after us, not the other way around! Started hassling us. They started it!”

“I don’t give a shit who started it,” Jones said. “As it happens, I agree that hiring young thugs off the streets as peacekeepers is about as stupid an idea as I’ve seen yet. Politicians in action. However, the Ring Seven Authority has requested that you be turned over to the civil sector for trial. The charges are aggravated assault and battery.”

Shit. Ramsey swallowed, hard. In most cases, civil law took precedence over military law, at least within Commonwealth territory. They could be looking at bad conduct discharges, followed by their being turned over to the civilian authority.

No … wait a moment. That wasn’t right. ABCD was a punishment that a court-martial board could hand out, not a commanding officer.

“Before we go any further with this … do any of you want to ask for a full court?”

That was their right under regulations. They could accept whatever judgment—and punishment—Jones chose to give them under nonjudicial punishment, or they could demand a court-martial.

But there was absolutely no point in that. They’d all been caught absolutely dead to rights—AWOL and fighting with the civilian authorities. Better by far to take whatever Jones chose to throw at them; whatever it was, it wouldn’t be as bad as a general court, which could hand out BCDs or hard time.

“How about it? Ramsey?”

“Sir,” Ramsey said, “I accept nonjudicial punishment.”

“That go for the rest of you yahoos?”

There was a subdued chorus of agreement.

“Very well. You all are confined to the ship for … three days. Dismissed!”

Outside the lieutenant’s office, the six Marines looked at one another. “That,” Colver said, “was a close one!”

“She could have come down on us like an orbital barrage,” Chu added. “Three days?”

“I don’t get it,” Delalzlo said, shaking his head. “A slap on the wrists. What’s it mean, anyway?”

“What it means,” Ramsey told them, “is she’s keeping us out of worse trouble. Two days from now we’re shipping out.”

They’d learned that fact yesterday, shortly after coming back on board the Samar, but with other things on their minds, they’d not made the connection. The civil authorities might request that the six miscreants be turned over to them for trial, but unless and until they were handed over, they were part of Samar’s company. The needs of the ship and of the mission always came first; by restricting them to quarters, Lieutenant Jones was making sure that the civilian authorities didn’t get them.

Marines always took care of their own.