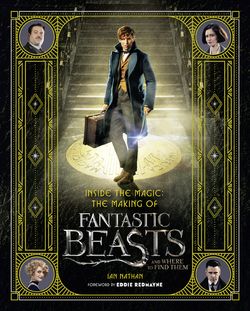

Читать книгу Inside the Magic: The Making of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them - Ian Nathan - Страница 8

A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO MAGIZOOLOGY

ОглавлениеPUBLISHED IN 2001 IN AID OF COMIC RELIEF AND OTHER CHARITABLE CAUSES, J.K. ROWLING’S FANTASTIC BEASTS AND WHERE TO FIND THEM IS THE FICTIONAL VERSION OF NEWT SCAMANDER’S TEXTBOOK FOR TEACHING CARE OF MAGICAL CREATURES.

Scamander, we are informed, is the wizarding world’s foremost Magizoologist. The fact this is a pursuit frowned upon by some of the magical community in Newt’s time (beasts are considered far too dangerous to be dabbling with), does not diminish a lifelong study of all the weird and wonderful creatures of the magical realm.

Written in Newt’s upbeat, lightly meticulous voice it was a slim but wholly delightful extension of the Harry Potter universe, and it got Lionel Wigram thinking.

The experienced British producer can still remember the momentous day in 1997 when his counterpart David Heyman sent over a copy of the debut novel by a then unknown author, saying he thought it would make a really good movie. Wigram was equally smitten. He still treasures that faded copy of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, even though, he admits, it’s not one of the 500 rare first edition copies credited to ‘Joanne Rowling’ and not ‘J.K.’, which have sold for upwards of £26,000.

Their instincts would, of course, prove spot on. Over the following fourteen years, Wigram was the Warner Bros. executive on the first four films and then the executive producer of the final four, which makes him, alongside Heyman, the longest-serving filmmaker in the Harry Potter world.

‘It’s been a great privilege, probably the greatest of my career,’ he says, and coming from a man who has also produced the big-screen Sherlock Holmes films and The Man from U.N.C.L.E., that means something.

J.K. Rowling’s storytelling is, he thinks, attuned to something universal and timeless, like in the great fairy tales. She understands the human condition. Profound ideas and themes are communicated in a way that’s very accessible and entertaining. ‘And that,’ he emphasizes, ‘is a very, very rare thing.’

When they finally brought the eight-film Potter saga to a close in 2011, he admits he felt bereft. ‘Was that really it?’ he wondered. ‘There had to be something more.’ However, J.K. Rowling had been adamant there were to be no more Harry Potter books. So Wigram began to think more and more about the possibilities in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.

‘Newt came to life for me on the page,’ he says, ‘this amazing character making his list of magical creatures, their different habitats, and how they behave. I couldn’t help imagining him traipsing through various exotic environments, and the adventures he would have along the way.’

Newt mixes a magical potion.

This newspaper fragment gives a clue to the location of the Appaloosa Puffskein.

Eddie Redmayne & Dan Fogler rehearse a scene with director David Yates.

The boom camera zooms in on Eddie Redmayne and Katherine Waterston surrounded by a sea of extras.

For J.K. Rowling, the relationship between her wizard and his beasts lay at the heart of her story: ‘Newt has an affinity for them, a love of creatures that goes beyond our innate desire to cuddle something cuddly. Newt finds beauty in the most dangerous creatures.’

Wigram wondered if it was possible to transform what is essentially a catalogue of outlandish faunae into a fictional nature documentary. He admits it was just the glimmer of something, but you would follow this very eccentric explorer in search of different creatures.

Warner Bros. was receptive to the idea. Here was a chance to keep the Harry Potter flame alive while pursuing something entirely new – extending the universe in modern Hollywood jargon. So they pitched it to J.K. Rowling.

‘I think she quite liked the idea,’ laughs Wigram, ‘and quite sensibly went off and came up with her own completely different story, which was much better, much richer, and more fantastic.’

J.K. Rowling explores the world of magic in New York in 1926. Newt Scamander has come to the city with his research almost complete, on his way to return a Thunderbird to its natural habitat in Arizona. But if asked, he will say that he’s merely looking to pick up an Appaloosa Puffskein for a friend’s birthday – one of the few Puffskein breeders is somewhere in the city. It will prove an eventful trip, filled with the full bounty of J.K. Rowling’s enchanting sensibility.

‘Nobody could possibly do it better than her,’ insists Wigram. ‘I don’t think anybody but the creator would dare to take the creative licence to push the boundaries, to give you something new.’ Rather than a series of new books, J.K. Rowling decided to cut out the middleman and compose the scripts herself, her first experience of writing directly for the screen.

‘I really, really, really enjoyed it,’ she confirms. ‘And that’s utterly different to being a novelist, where you’re alone for a year, completely alone for a year, and then one person gets to read it. I thought, you know, I really want to write this screenplay. There’s a story I want to tell.’

The camera looks up to Eddie as it films Newt’s arrival at the Customs Hall.

Even though she was exploring a ‘new muscle group,’ director David Yates has been flabbergasted at how easily she has adapted to the task.

‘She can turn on a six-pence,’ he says, amazed not just by her gifts for storytelling but her speed. Yates and producer Steve Kloves (responsible for seven of the eight screenplays for the Harry Potter films) would sit with J.K. Rowling, feeding through ideas from producers Heyman and Wigram at every stage. Every note sent her off in a fascinating new direction.

J.K. Rowling would then depart for her hotel and spend two nights at her keyboard, returning having not slept but rewritten huge portions of the script, sometimes producing an entirely new draft. Yates was staggered by the sheer output of that imagination. Even while making their changes she would come up with something entirely new. ‘I know it’s crazy but I just had to do it,’ became almost a catchphrase.

‘She doesn’t have any of the fear,’ says Yates. ‘She doesn’t have any of the experience of working in a system where ideas are constantly knocked back.’

If there was any downside at all it was that J.K. Rowling fed them too much goodness. As they homed in on the kernel of their story, she would provide layers of incredible detail, entire histories for even the most marginal character. ‘She has so much flowing through her head,’ says Yates, and he had to politely suggest they postpone some of her ideas to later movies.

It was never an issue. The director can look back on an entirely positive process. There were no prickly egos to negotiate, only a shared sense of purpose and the honesty that comes with familiarity.

‘There’s a huge amount of responsibility and pressure to go back to this universe and deliver something special,’ he admits, ‘but that is easier to bear when you are with friends and colleagues that you’ve worked with before.’

The finished script cast a remarkable spell – it was a Harry Potter film that was not a Harry Potter film. While set in the same wizarding world with many shared reference points – not least that Scamander is a former pupil of Hogwarts – this was a different kind of magical film. One less about the fulfilment of a childhood destiny than the consequences of magic spilling out into the real world, albeit one as thrilling as New York in the 1920s. Newt has to fix his own mistakes, and in doing so fix himself. It is a film about grown-ups learning to grow up.

The wizard looks to be in jeopardy in MACUSA’s Death Cell.

Newt’s leather journal is decorated with a gold monogram of his initials.

Concept art by Peter Popken of Newt’s steamship arriving in New York.

When several of Newt’s fantastic beasts escape from his battered leather case, Newt must reclaim his extraordinary escapees before they become front-page news in one of the newspapers belonging to magnate Henry Shaw Sr. (Jon Voight). He is aided in his dilemma by a disgraced Auror (one of the wizarding world’s police force) named Porpentina ‘Tina’ Goldstein (Katherine Waterston), as well as her beautiful, free-spirited younger sister Queenie (Alison Sudol). And, indeed, a luckless No-Maj (the American wizarding community’s word for Muggle), and aspiring baker named Jacob Kowalski (Dan Fogler), who is about to have his horizons significantly widened. Assuming that no one Obliviates his memory.

Complicating matters, New York is not receptive to magic. Led by the glowering Mary Lou Barebone (Samantha Morton), The New Salem Philanthropic Society (or ‘Second Salemers’) agitates on street corners about the threat of a magical revival. Mary Lou has in tow three sullen, adopted children: Credence (Ezra Miller), Chastity (Jenn Murray) and Modesty (Faith Wood-Blagrove). Credence, especially, appears to be deeply troubled.

The Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA) therefore has to operate in secret and any public demonstrations of magic are expressly forbidden, by either man or beast. Suave, elusive Percival Graves (Colin Farrell), Director of Magical Security and head of the Auror division, is paying very close attention to what Newt and Tina are up to. And as Newt’s ship docks, an even greater peril has stirred in Manhattan – one that could have far more dangerous consequences than the odd missing Niffler or Erumpent.

All of the filmmakers are keen to point out the themes that run through the story. Darker ideas concerning prejudice and repression, and ecological and political veins that touch upon the way our world works right now. And more intimately, the Rowlingesque celebration of discovering kinship in the unlikeliest places, and being who you are without apology.

‘Jo is interested in outsiders, people who are misunderstood or slightly out of kilter with the rest of society,’ says David Yates. ‘In this case one of our characters, Newt Scamander, is an outsider because he’s a Brit in New York. He’s an outsider because he believes and cherishes and collects extraordinarily dangerous, beautiful, exotic magical beasts that are banned from the wizarding world. So he’s a classic Jo outsider. Yet he hooks up with some other characters in New York and sort of finds intimacy with them. It’s really a beautiful journey for Newt.’

A MAGIZOOLOGIST’S UNIFORM

Costume designer Colleen Atwood calls Newt an ‘off-the-page character’. Everything she needed to know about him was right there in the script. ‘He’s been living in the wilderness,’ she says. ‘Therefore he adapts everything to what he needs in his own world.’

Nevertheless, he still needed to be able to blend in with the world of the 1920s. The trick was to take the general look of the age – what Atwood likes to call its ‘silhouette’ – and make his clothes a little mismatched and ill-fitting. There would be something quirky about him, but not clownish. If there tended to be a lot of warm tones in the menswear of the era – browns and so forth – Newt would wear something cooler.

‘So I chose a dirty peacock blue for his coat,’ Atwood explains, ‘and that was sort of his defining look – he wears that the most. The layers underneath sort of work with the jungle and other places that he has been.’

Naturally, there would be more to Newt’s overcoat than meets the eye. ‘We had all kinds of pockets that had purposes in the script,’ says Atwood, whose designs are as influenced by requirements of plot as much as character. ‘His little friends hide in there and then he has some of his medicines in there, and his cures. So I researched magician’s coats and learned how they had all these secret pockets.’

Atwood actually begins her design process during rehearsal, studying how an actor moves, all the little character traits he might be giving the part. The most important element in any costume is how it fits not just an actor’s body but also their performance. Reaching that indefinable moment when actor, role and costume become one and the same. And she loves how Eddie Redmayne became ‘integrated’ with his costume. ‘He sort of lives in it,’ she laughs. ‘He makes it feel like his own clothes.’

Redmayne has loved that he really only wears one outfit the whole way through the film, but changes as he does: ‘The collar pops open. The trousers go into his boots. I suppose there’s a slightly eccentric, nerdy quality to him that turns into more like an adventurer by the end of the film.’

Sketch shows how the interior of Newt’s coat might look. Costume designed by Colleen Atwood, drawn by Warren Holder.

‘WE HAD ALL KINDS OF POCKETS THAT HAD PURPOSES IN THE SCRIPT’