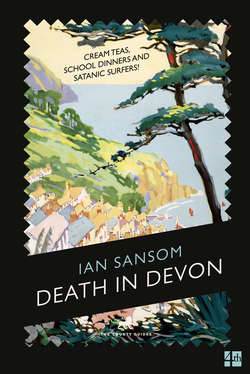

Читать книгу Death in Devon - Ian Sansom - Страница 9

CHAPTER 1 GOOD TO BE BACK

Оглавление‘AH, SEFTON, MY FECKLESS FRIEND,’ said Morley. ‘Just the man. Now. Rousseau? What do you think?’

He was, inevitably, writing one of his – inevitable – articles. The interminable articles. The inevitable and interminable articles that made up effectively his one, vast inevitable and interminable article. The über-article. The article to end all articles. The grand accomplishment. The statement. What he would have called the magnum bonum. The Gesamtkuntswerk. ‘An essay a day keeps the bailiffs at bay,’ he would sometimes say, when I suggested he might want to reduce his output, and ‘The night cometh when no man can work, Sefton. Gospel of John, chapter nine, do you know it?’ I knew it, of course. But only because he spoke of it incessantly. Interminably. Inevitably. It was a kind of mantra. One of many. Swanton Morley was a man of many mantras – of catchphrases, proverbs, aphorisms, slang, street talk and endless Latin tags. He was a collector, to borrow the title of one of his most popular books, of Unconsidered Trifles (1934). ‘It takes as little to console us as it does to afflict us.’ ‘Respice finem.’ And ‘May you never meet a mouse in your pantry with tears in his eyes.’ Morley’s endless work, his inexhaustible sayings, were, it seemed to me, a kind of amulet, a form of linguistic self-protection. Language was his great superstition – and his saviour.

To stave off the universal twilight that evening Morley had rigged up the usual lamps and candles, and had his reams of paper piled up around him, like the snow-capped peaks of the Karakoram, or faggots on a pyre, like white marble stepping stones leading up to the big kitchen table plateau, where reference books lay open to the left and to the right of him, pads and pens and pencils at his elbow, his piercing eyes a-twinkling, his Empire moustache a-twitching, his brogue-booted feet a-tapping and his head a-nodding ever so slightly to the rhythms of his keystrokes as he worked at his typewriter, for all the world as if he were an explorer of some far distant realm of ideas, or some mad scientist out of a fantasy by H.G. Wells, strapped to an infernal computational machine. A glass and a jug of barley water were placed beside him, in their customary position – his only indulgence.

It was already well after midnight. I had returned to Norfolk and St George’s after two days in London, attempting to put my affairs in order and succeeding only in disordering them further.

‘Rousseau?’ I said. It was my job in these exchanges, I had soon realised, to bat the ball gently back to him, the warmup to his Fred Perry, as it were, throwing him balls or titbits, that he might leap up and devour them. ‘My interlocutor’, he would sometimes introduce me to new acquaintances, or, alas, worse, ‘My bo’, one of those terribly unfortunate phrases he’d picked up from his beloved hard-boiled detective stories, and which got us into a number of scrapes over the years. Damon Runyon, Ellery Queen: I could never quite understand his enthusiasm for purveyors of what he might, in the argot, have called shtick.

‘Rousseau. Yes.’ I was finding it hard to think. I had, admittedly, in London, been drinking and indulging, even though I had promised myself not to return to my former habits and haunts, but had found it impossible to resist. Just forty-eight hours away from Morley and his high thinking and I had descended back down to the depths of my depravities.

‘Come, come, Sefton. Rousseau?’ He clapped his hands.

‘Well …’ I’d managed to catch the last train out of Liverpool Street for Norfolk, in the full knowledge that if I stayed a day longer the die would be cast for ever, and I would be adrift and out of employment again, at the mercy of Messrs Gabbitas and Thring, and worse …

‘Hello? Dial 0 for operator?’ He rapped his knuckles against the table. ‘Hello? Operator? It’s ringing for you, caller! Remind me why I employed you again, Sefton?’

I had at that stage been Swanton Morley’s amanuensis, his assistant, and his ‘bo’ for approximately two weeks. And I had to admit that – apart from my time in Spain – it had been the strangest, most utterly disorientating and exhilarating two weeks of my life. It had also – not insignificantly – helped to solve certain personal and practical problems I had been facing in London. Which is why, after a hectic few days, I had returned again to the wilds of Norfolk ready to clock in promptly for work on Monday morning.

‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau,’ I offered, fossicking around in my rather disordered mental store cupboard. ‘Philosopher. Educationalist—’

‘No! No! No! Come on, man. Wrong Rousseau!’ said Morley. ‘Henri. Or Henri, pronounced in the continental fashion.’

‘Ah.’ As if I should have known which continental Rousseau he had in mind.

‘Here, here. Come, come, come.’

Morley beckoned me towards him. I edged carefully around the books and papers and looked over his shoulder at one of the large volumes spread out on the desk.

‘Well. What do you think of that?’

The moon shone down brightly from the high window above the table, illuminating the book, which showed an illustration of an extraordinarily vivid, disturbed sort of painting, like the work of a brilliantly gifted child, depicting what was presumably supposed to be a lion sinking its teeth into what was presumably an …

‘Anteater?’ I said.

‘Antelope,’ said Morley. ‘Though granted it’s not entirely clear. The gaucheries of the self-taught, eh, Sefton?’

‘Yes.’

‘Not that you’d know anything about that, eh?’

‘Well, no’ – my privileged upbringing and education were a constant source of amusement to Morley, who had raised himself by his proverbial bootstraps, and who found it hard to take anyone seriously who did not possess bootstraps that needed raising – ‘although—’

‘Quite extraordinary,’ he said.

‘Quite extraordinary,’ I agreed. ‘Remarkable.’ I was rather groggy from the after-effects of my journey, and all the tobacco, and drink and too little sleep – and even under the best of circumstances it was simply easier to agree with Morley.

He turned the page to another illustration. A lion eating a leopard. And another page: a tiger attacking a water buffalo. And another: a jaguar bringing down a white horse.

‘Wonderful stuff, isn’t it, Sefton?’

‘It’s certainly … interesting, Mr Morley,’ I agreed.

‘Interesting?’ he said. ‘Interesting?’ ‘Interesting’, I learned over time, was a trigger word. There were others. ‘Literally’, for example, used incorrectly, would send him – literally – mad. ‘Effect’, as a cause, infuriated him. His ‘instant’ was never quick. And he could never see the irony in ‘irony’. His moustache bristled. ‘Is that really an aesthetic category, Sefton, do you think? Interesting? Hmm? Acceptable to the philosophers and critics of taste in your alma mater, in the old wisteria-swagged ivory towers of Cambridge, do you think? Mr Wittgenstein? Mr Leavis? “Interesting”? A common term of approbation among your peers, is it?’

‘Well …’

‘God save us from “interesting”, Sefton. God Himself save us. Jesus Christ? Hmm? What do you think?’

‘What do I think about Jesus Christ, Mr Morley?’

‘“Interesting” sort of fellow, would you say? And what about – I don’t know, take your pick – Tutankhamun? Captain Scott? Napoleon? Christopher Columbus? Any of them “interesting” in your books? J.M.W. Turner perhaps? J.S. Bach? “Interesting” at all, at all, at all?’

‘Erm …’

‘Never left France, Rousseau.’ Morley suddenly switched tack, as he was wont to do. ‘All this exotica derived entirely from images in books and magazines. And up here, of course.’ He tapped his head with his fingers, one of his favourite gestures in his wide repertoire of gestures: he would have made a fine actor in rather broad Shakespearean roles, I always thought, or perhaps an understudy to Charles Laughton, though in looks of course, as has often been remarked, he resembled rather more a mustachioed Fritz Leiber, in his heyday in The Queen of Sheba. ‘And the Jardin des Plantes,’ he continued. ‘Dioramas in museums and what have you – look at the lion there, looks like a stuffed toy, doesn’t it? Product entirely of the imagination, Sefton. An orchestration of images, ideas and desires. And yet an instinctive understanding of the mysteries of the tropical, wouldn’t you say? Look at that undergrowth.’

‘Yes.’

‘I think our friend Herr Freud would have something to say about Rousseau, wouldn’t he, eh? Monsieur Henri, eh? Eh?’

‘I’m sure he would, Mr Morley.’ Though I wasn’t sure entirely what it was Freud would have to say. Nor did I entirely care.

‘Hmm.’ He stroked his moustache. ‘The tangles, you see, Sefton. Tangles. Tangles. You see the tangles?’ I saw the tangles. ‘And the deep lush vegetation. Vines. Lianas. Terrible confrontations in deep dusky dells with mysterious hairy beasts. Look at these gashes and wounds here.’

‘Yes.’

‘One doesn’t have to be Viennese, I think, to have a guess, does one?’

‘No, Mr Morley.’ Or rather, What, Mr Morley? (Which is of course the title of his famous series of books of notes and queries, published annually, containing answers to questions posed in the form of the book’s title, thus, ‘What, Mr Morley, is the meaning of the term mah nishtana, which I have heard some of my Jewish neighbours exclaim, and which I believe may be either Hebrew or the Jewish language of Yiddish?’, or ‘What, Mr Morley, is the best way to remove coal dust from my antimacassar?’)

‘Not quite top rank though, is it?’ continued Morley. ‘In all honesty? I think we’ll grant him an accessit, shall we?’

‘A—’

‘Second prize medal. Forgotten all your Latin?’

‘Ahem. Well. That sounds about …’

‘The great untaught, you see, Sefton. All that power and originality combined with sometimes shocking naivety. The child’s perspective, one might say. The sublime cheek by jowl with the ridiculous. One of life’s great mysteries, wouldn’t you say?’

I couldn’t have agreed more.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Good.’

‘And who’s the article for, Mr Morley?’

‘Sunday Graphic. Just a little jeu d’esprit, as Mr Rousseau himself might say.’

He poured himself a fresh glass of barley water, and stared at me inquisitively.

‘So, my young fellow, how was London?’

‘It was fine, thank you, sir.’ I never spoke to Morley about my other life. It did not seem appropriate.

‘Good. Good. You’ll be delighted to know that in your absence I’ve finished Norfolk.’

‘Finished it?’

‘That’s correct. Aquila non capit muscas and what have you.’

We had only returned from our first adventure around the English counties on Sunday. This was a week later. Which meant that he had written a book … in a week?

It took me a moment to gather my powers of speech.

‘But I thought we were going to …’

‘We have a strict schedule to stick to, Sefton, remember. If we’re going to cover everything by 1940. Uphill all the way, I’m afraid. No time for slacking.’

‘No, of course.’

‘Or shilly-shallying.’

‘No.’

‘Or funking.’

‘No, absolutely. No slacking. No shilly-shallying. No funking.’

‘Precisely! So I took the liberty of writing up most of my notes myself – to save you time. You’ll be copy-editing and proofing this week. We want to have it more or less ready for the presses within two weeks. Photographs and what have you. Excellent photographs, by the way, Sefton – though a little bit more artistic, next time, eh?’

‘More artistic, Mr Morley?’

‘Well, you know. Something a bit more … Man Ray perhaps?’

‘Really? Man Ray?’

‘Yes, you’ve come across him?’

‘I think so, yes.’

‘Or … I don’t know, maybe not Man Ray, Sefton. But something. We need to capture the public’s imagination, man. Give them something new. Something fresh. Something … unexpected.’

‘I’ll do my best, Mr Morley.’

‘Good! Bit of experimentation, man. But not too much.’

‘Very good, Mr Morley.’

‘And then as I say, we should have everything ready for publication by the end of October. The County Guides – book number one.’

‘That’s … good.’

‘And in the meantime we shall move on swiftly to book number two.’

‘Right. I’ll be staying here then, to do the copy-editing and proofing on book one?’

‘Here?’

‘St George’s? Norfolk?’ I could imagine myself curled up by the fire in the library, leisurely correcting Morley’s proofs, cigarettes and coffee to hand.

‘Not at all, not at all, not at all, Sefton. Not. At. All. No, no, no. We’re all packed and ready to go again, my friend, first thing in the morning. You’re going to have to get accustomed to the pace of life here, old chap. You’ll be editing en route to our next county.’

‘I see.’ I was tired already. ‘Will Miriam be joining us?’

‘She will, indeed. For better and for worse. Until you’ve got the hang of things.’

‘I think I’ve probably—’

‘Also, she needs to … get away for a while. I have spoken to you about Miriam before, Sefton, you will recall.’ He narrowed his eyes rather as he spoke.

‘Yes.’

‘And you have clearly understood my concerns?’

A bit of experimentation

‘Yes, yes, of course, Mr Morley.’

‘Wild.’ He shook his head. ‘Untameable.’

‘Well, I wouldn’t say—’

‘And it’ll take a better man than you to tame her, Sefton. With all due respect. There’s talk of another engagement …’

‘I see.’

He gazed up at the window above the desk. It was a clear night sky.

‘There’s a storm coming.’

It wasn’t immediately clear to me whether he was speaking literally or metaphorically; he spoke often of gathering storms. It wasn’t always clear whether he meant rain, or Miriam’s doomed engagements, or the imminent collapse of human civilisation. Or all three.

‘Do you ever think about the future, Sefton?’

‘Occasionally, Mr Morley. Yes, I do.’

‘And when you think about the future, what do you think?’

‘Erm …’ An answer, obviously, was not required.

‘When I think about the future, Sefton, I think that what we are doing now will be seen largely as an irrelevance, alas. The book will become a decorative art object, and as for newspapers …’ He shook his head. ‘There will be endless wars. Famines. And the England that we know and love will have entirely disappeared. We will achieve a classless society, not because we have all been raised to new heights, but rather because we have all been dragged down to the same depths.’ When speaking of heights and depths, Morley illustrated the point with his usual gestures.

‘I see.’ This was a version of a speech I had already heard him utter on numerous occasions.

‘People’s bodies will seize up, Sefton, due to their unthinking reliance on machines. Men and women will balloon in size, like vast blimps, and go bouncing around our towns and cities, crushing one another in their hurry to acquire more and more of less and less that is truly good. Don’t you think it’s possible, Sefton?’

‘It’s certainly not im—’

‘But one day, I believe, man will overcome himself. He will rise from his slumber. He will slip the bounds and trammels of this earth. He will transcend his small concerns and reach for the stars! He will travel … to the moon! Do you think it’s possible, Sefton?’

‘Again, it’s entirely—’

‘Not in my lifetime, perhaps. But in yours. It will be wonderful: an opportunity to start all over again, eh? Not granted to every man, Sefton, is it?’

‘No, Mr Morley.’

‘But in this brave new world I believe there will be so much going on that no one will care to remember what we have lost.’

‘Indeed.’

‘Which is our task, of course, Sefton! To act as recording angels, if you like. No more. No less. Quite a calling though, eh?’ His rambling speech seemed to have cheered him – as his rambling speeches so often did. I wondered sometimes if he spoke merely for the sole purpose of his own encouragement.

‘Yes. Indeed.’

He stared at me again. ‘You seem rather liverish this evening, Sefton, if you don’t mind my saying.’

‘Yes, well, I …’

‘Time for your beauty sleep, perhaps.’

‘Well, I am rather tired, Mr Morley.’

‘Raram facit misturam cum sapientia forum, Sefton.’

‘Quite. So … unless there’s anything I can do for you here …’

‘No, no, no. The cottage won’t be ready for a while, I’m afraid. I’ve spoken to Wilson about it. It’s going to need quite some fixing up. In the meantime we’ll put you upstairs in one of the attic rooms, if that’s still OK? Same room as before. All set up for you.’

‘That’s wonderful, thank you.’

‘Eaten?’

‘I had a sandwich at Liverpool Street.’

‘Cheruntis pabulum! You can find yourself something in the kitchen if you’d like. Cook made a wonderful mutton and parsnip soup a few days ago. It’s maturing rather nicely.’

‘No, thank you.’

‘What’s the Korean dish?’

‘I’m not sure, Mr Morley.’

‘Kimchi! That’s it. Rather reminiscent. I was there just after the Japanese occupation. Pretty grisly. Merciless … Anyway. Probably best to avoid the soup in your condition. I’ll bid you goodnight. Must just finish this.’ And with that he turned back to his books and his typewriter, and the endless words began to flow again.

Upstairs, as I walked down the long corridor towards my room up in the attic, the echo of Morley’s typewriter in the distance, a door happened to open and Miriam walked out. She was smiling inwardly, it seemed to me: there was a look of satisfaction on her face, of satiation, one might almost say, as if she had … Well … I had enjoyed a rather long weekend in London and was tired; my imagination was doubtless running away with me. Her hair, I noted, was a blonder shade of blonde than I remembered, her cheeks were flushed, and she was wearing a nightgown made of a silvery silk, creating an effect that in the half-lit corridor might be described as simultaneously ethereal and electrifying, shuddering almost, as if one had bumped into Carole Lombard herself, made-up, half dressed, lit, on set, and ready to take her call …

‘Oh, Sefton. You’re here!’ she gasped, clutching her nightgown more closely to her. ‘Sorry, I was just …’

‘Yes. Good evening, Miss Morley.’

‘Back for more then? We haven’t put you off?’

‘No. No. Not at all.’

‘You were in London?’

‘Yes, I was.’

‘I hope you had fun?’

‘I … did. Yes. Certainly.’

‘Good. I think we’re going to have fun, aren’t we, Sefton?’ She was standing alarmingly close to me at this point, so close that I began to feel rather vulnerable, like the poor antelope in Rousseau’s painting.

‘I’m sure we will, Miss Morley.’

‘You … and me,’ she said.

‘And your father, of course.’

‘Hmm.’

She walked off then, turning only to wave goodnight and to cast the mystery of her smile before me, like a cryptic invitation, or a code I was supposed to crack.

I entered my room and lay down on my bed, exhausted.

God, it was good to be back.