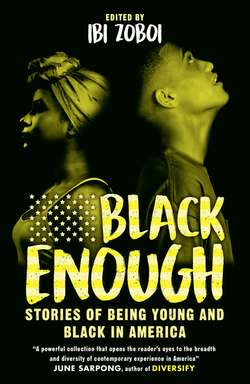

Читать книгу Black Enough: Stories of Being Young & Black in America - Ibi Zoboi - Страница 7

INTRODUCTION IBI ZOBOI

ОглавлениеI was born in a country known for having had the first successful slave revolt in the world. Way back in 1804, Haiti became the very first independent Black nation in the Western Hemisphere. If global Blackness had a rating scale of one to ten, the Haitian Revolution has got to be at level ten, being the most Blackest thing that ever happened in history.

But none of that mattered when I first immigrated to the United States as a child. The Black and Latinx kids in my Brooklyn neighborhood didn’t know and didn’t care that my native country had once been a hub for freed slaves from America. According to them, I wasn’t Black enough. I wore ribbons in my hair and fancy dresses to school, and I had a weird accent and a funny name. Most important, I didn’t know how to jump double Dutch or separate a sunflower seed from its shell with just my front teeth, and I was off-key and off-beat when stomping, clapping, and singing to the latest cheers. These were all definitions of Brooklyn’s summertime Black girlhood.

By the time I started high school, I had mastered all of those things and could easily blend into New York’s particular brand of teen Blackness, even while tucking away the quirky parts of myself—my love of sci-fi, disco music, and John Stamos.

In college, my small Black world expanded when I met my first roommate, who had the thickest Southern accent I had ever heard. My best friend in high school was African American and I’d been to her big family cookouts and even to visit her cousins in a small Black town in South Carolina. I’d been a little jealous that she had such a big family and at a moment’s notice could be surrounded by a plethora of aunts, uncles, and cousins. This was my first glimpse into African American culture—one with deep roots in the South. But that new roommate of mine with the Southern accent was from Rochester, New York, and her family had lived there for as long as she could remember.

Once I met new friends from Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, and even England, my idea of Blackness began to expand. It was only then that I started to connect my own Brooklyn Blackness to a global idea of Blackness. After all, while the girls in my neighborhood teased me about not knowing how to spit out sunflower seeds, they didn’t know how to properly eat a mango, or know Creole or Patois or any of the Caribbean ring games. But before long, I knew there was a fine thread that connected all of these cultural traditions to each other.

Blackness is indeed a social construct. Within the context of American racial politics, there can be no Black without white. No racism without race. But the prevalence of culture is undeniable.

What are the cultural threads that connect Black people all over the world to Africa? How have we tried to maintain certain traditions as part of our identity? And as teenagers, do we even care? These are the questions I had in mind when inviting sixteen other Black authors to write about teens examining, rebelling against, embracing, or simply existing within their own idea of Blackness.

Renée Watson’s opening story, “Half a Moon,” places Black teen girls outdoors, among trees, and swimming in lakes—and yes, there is the common understanding that the hair situation is already handled. Jason Reynolds and Lamar Giles fully capture #blackboyjoy in their respective stories “The Ingredients” and “Black. Nerd. Problems.” There are no pervasive threats to their goofing around and being carefree. The intersectional lives of teens who are grappling with both racial and sexual identity are rendered with great care and empathy in Justina Ireland’s “Kissing Sarah Smart,” Kekla Magoon’s “Out of the Silence,” and Jay Cole’s “Wild Horses, Wild Hearts.” From Leah Henderson’s story of appropriation at a boarding school to Liara Tamani’s story of inappropriate nude pic games at a church beach retreat, the teens in Black Enough are living out their lives much like their white counterparts. They are whole, complete, and nuanced.

Like my revolutionary ancestors who wanted Haiti to be a safe space for Africans all over the globe, my hope is that Black Enough will encourage all Black teens to be their free, uninhibited selves without the constraints of being Black, too Black, or not Black enough. They will simply be enough just as they are.