Читать книгу Consorts of the Caliphs - Ibn al-Sa'i - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеكتاب جهات الأئمّة الخلفاء من الحرائر والإماء

المسمّى

نساء الخلفاء

لتاج الدين عليّ بن أنجب المعروف بٱبن الساعي

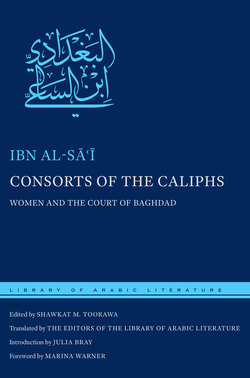

Consorts of the Caliphs

Women and the Court of Baghdad

Ibn al-Sāʿī

Edited by Shawkat Toorawa

Translated by the Editors of the Library of Arabic Literature

Introduction by Julia Bray

Foreword by Marina Warner

Volume editor Julia Bray

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

Table of Contents

Letter from the General Editor

Abbreviations

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Maps

Note on the Edition

Note on the Translation

Notes to the Frontmatter

Consorts of the Caliphs

1. Ḥammādah Daughter of ʿĪsā

2. Ghādir

3. ʿInān, daughter of ʿAbd Allāh

4. Ghaḍīḍ

5. Haylānah

6. ʿArīb al-Maʾmūniyyah

7. Bidʿah al-Kabīrah

8. Būrān

9. Muʾnisah al-Maʾmūniyyah

10. Qurrat al-ʿAyn

11. Farīdah

12. Isḥāq al-Andalusiyyah

13. Faḍl al-Shāʿirah al-Yamāmiyyah

14. Bunān

15. Maḥbūbah

16. Nāshib al-Mutawakkiliyyah

17. Fāṭimah

18. Farīdah

19. Nabt

20. Khallāfah

21. Ḍirār

22. Qaṭr al-Nadā

23. Khamrah

24. ʿIṣmah Khātūn

25. Māh-i Mulk

26. Khātūn

27. Banafshā al-Rūmiyyah

28. Sharaf Khātūn al-Turkiyyah

29. Saljūqī Khātūn

30. Shāhān

31. Dawlah

32. Ḥayāt Khātūn

33. Bāb Jawhar

34. Qabīḥah

35. Sitt al-Nisāʾ

36. Sarīrah al-Rāʾiqiyyah

37. Khātūn al-Safariyyah

38. Khātūn

39. Zubaydah

Notes

The Abbasid Caliphs

The Early Saljūqs

Chronology of Women Featured in Consorts of the Caliphs

Glossary of Names

Glossary of Places

Glossary of Realia

Bibliography

Further Reading

Index of Qurʾanic Verses

Index of Verses

About the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute

About this E-book

About the Editor and Translators

Library of Arabic Literature

Editorial Board

General Editor

Philip F. Kennedy, New York University

Executive Editors

James E. Montgomery, University of Cambridge

Shawkat M. Toorawa, Cornell University

Editors

Julia Bray, University of Oxford

Michael Cooperson, University of California, Los Angeles

Joseph E. Lowry, University of Pennsylvania

Tahera Qutbuddin, University of Chicago

Devin J. Stewart, Emory University

Managing Editor

Chip Rossetti

Digital Production Manager

Stuart Brown

Assistant Editor

Gemma Juan-Simó

Letter from the General Editor

The Library of Arabic Literature is a new series offering Arabic editions and English translations of key works of classical and pre-modern Arabic literature, as well as anthologies and thematic readers. Books in the series are edited and translated by distinguished scholars of Arabic and Islamic studies, and are published in parallel-text format with Arabic and English on facing pages. The Library of Arabic Literature includes texts from the pre-Islamic era to the cusp of the modern period, and encompasses a wide range of genres, including poetry, poetics, fiction, religion, philosophy, law, science, history, and historiography.

Supported by a grant from the New York University Abu Dhabi Institute, and established in partnership with NYU Press, the Library of Arabic Literature produces authoritative Arabic editions and modern, lucid English translations, with the goal of introducing the Arabic literary heritage to scholars and students, as well as to a general audience of readers.

Philip F. Kennedy

General Editor, Library of Arabic Literature

For Marianne

Abbreviations

| ad | anno Domini = Gregorian (Christian) year |

| ah | anno Hegirae = Hijrah (Muslim) year |

| art. | article |

| Ar. | Arabic |

| c. | century |

| ca. | circa = about, approximately |

| cf. | confer = compare |

| d. | died |

| ed. | editor, edition, edited by |

| EI2 | Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second edition |

| EI3 | Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three [Third edition] |

| EIran | Encyclopaedia Iranica |

| esp. | especially |

| f., ff. | folio, folios |

| fl. | flourished |

| lit. | literally |

| MS | manuscript |

| n. | note |

| n.d. | no date |

| n.p. | no place |

| no. | number |

| p., pp. | page, pages |

| pl. | plural |

| Q | Qurʾan |

| r. | ruled |

| vol., vols. | volume, volumes |

Foreword

“Muted” was the epithet used to describe female subjects by the anthropologists Edwin and Shirley Ardener in an influential critique of their discipline and its methods, published in 1975; they identified a systemic problem, that fieldworkers consistently sought out the men’s story, set down what they heard, and attended above all to male activities; in most cases, the researchers had little access to women, but they also did not try to listen to them or elicit their stories.1 Consequently, women disappeared from the record, their voices were not registered, and the whole picture suffered from distortion.

The Ardeners provided a polemical but persuasive angle of view on a widespread discomfort with cultural assumptions, and their work spurred a new generation of readers and researchers to begin listening in to “muted groups” of individuals from the past, those muffled female participants whose “labour created our world” (to borrow Angela Carter’s phrase about storytellers, ballad-singers, and other cultural keepers of memory). The impulse was part of the broadly feminist program of those years, but it grew larger than that political movement, as scholars in history, literature, social studies, and indeed almost every area of inquiry pursued the new archaeology, unearthing remarkable new material about women’s lives and deeds, and often bringing forgotten figures back to consciousness. The findings did not only fill in gaps in the view, but also transformed the whole horizon and realigned contemporary understanding in crucial ways. Historians such as Natalie Zemon Davis and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie excavated provincial archives and tuned in to the voices of female witnesses and defendants; literary scholars returned to and in some cases revived familiar and not unsuccessful writers (Christine de Pisan, Christina Rossetti, Emily Dickinson) to illuminate the social and psychological radiation of their works as women. Some of the ignorance—and the bigotry that arises from ignorance—began to lift, with many powerful reverberations for the position of women today. It is sobering to remember that less than a hundred years ago, Oxford and Cambridge did not award degrees to women (until 1920 and 1947 respectively), though they had begun to allow women to sit (successfully) for the exams. Now women have reached numerical parity at undergraduate and graduate levels in many subjects, and have entered every discipline as teachers and professors—Maryam Mirzakhani has won the Fields Medal in Mathematics and Julia Bray holds the Laudian Chair of Arabic at Oxford. (I do realize that Julia Bray, as project editor of this volume, may dislike being singled out for praise, but her appointment seems to me a great cause for pride and pleasure, and so I hope she will not mind my drawing attention to it.)

If low expectations, combined with misunderstanding and social prejudice, have muted women in the Western tradition, the silence that has wrapped women in the East is even deeper. In the United States and Europe, the voices of women from the Islamic past are often eroticized and trivialized—through harem romances and desert epics, advertising and propaganda. Rimsky-Korsakov’s luscious music for Shéhérazade was adapted for Fokine’s ballet of 1910 and accompanies a plot in which orientalist assumptions of savagery, lasciviousness, slavery, and tyranny are taken to torrid extremes. Ways of selecting and presenting stories from the Arabian Nights have exacerbated the problem: heroines who are adventurous and courageous and have strong, interior passions and resourceful ideas (Zumurrud, Badr, Tawaddud, and many others—they abound in the work) were overlooked in favor of the insipid love interest, like the princess in Aladdin, who is almost entirely silent and, when she does speak, foolish. Collections of the Arabian Nights selected for children frequently cut the frame tale and present the Nights as a bunch of stories, without the decisive organizing principle provided by Shahrazad’s stratagem, thus muting the female storyteller as pictured in the book and omitting the crucial rationale, her ransom tale-telling.

Consorts of the Caliphs is a work of historical biography, not an anthology of fictions, and it gives voice to the spirited, learned, influential women of the medieval past in the Abbasid empire. It unbinds our ears and eyes to some of what they said and did. The author/compiler Ibn al-Sāʿī was himself a poet and a librarian, and through patient sifting of archival memories, both oral and written, he communicates precious echoes and fragments from a period spanning five hundred years: the earliest woman whose life he sets before us was the wife of Caliph al-Manṣūr (reigned 136–58/754–75), while the latest, Shāhān, died in 652/1254–55. In the entry on Zubaydah, who died in 532/1137–38, Ibn al-Sāʿī’s epitaph is brief: “She was lovely and praised for her beauty.” This is uncharacteristically reticent. For the early years, Ibn al-Sāʿī fills in the blanks with stories he has gathered from chains of sources; for the later period, within living memory, he passes on what he has heard. Women’s words rise from the page in many registers—passionate high poetry, mordant quips and sallies, and prayerful thoughts. The effect is vivid and fleeting, a series of lantern slides within a laconic yet impassioned account that comes across clearly now and again but then breaks up or fades. Slaves, “dependents,” lovers and wives are glimpsed—dazzlingly accomplished individuals in some cases, who survive by their wits, risking all with their tongues; their adopted sobriquets give a flavor of their spiritedness: Ghādir (“Inconstance”), Ghaḍīḍ (“Luscious”), Qurrat al-ʿAyn (“Solace”), Ḍirār (“Damage”), Sarīrah (“Secret”), and even Qabīḥah (“Ugly”).

In other cases, the women, august or beggared, full of years or plucked before their time, pass by in a roll of honor, on a pervasive note of reverence and elegy. Ibn al-Sāʿī’s book conveys their mobility, the complexity of the roles they fulfilled, the variety of their ethnic and religious origins, and their high status. Their circumstances reveal the intermingling of ethnic origins and faiths. The term “slave” itself, used here after careful thought on the part of the translators and their editors, clearly needs more attention from historians, since the term, as habitually used in English, does not capture the ambiguities in the situation of Faḍl, for example, whose raunchy flytings the translators have met with matching boldness:2

He moaned and groaned and whined all night,

And creaked just like a door-hinge.

Some of Ibn al-Sāʿī’s material reads like fabulist literature. Anecdotes and personalities have intermingled with the stories of the Arabian Nights and grown into the stuff of legend: the passion of Maḥbūbah and al-Mutawakkil, for instance, a brief, dramatic tale of mutual dreaming and reconciliation, appears in the complete cycle of the Arabian Nights (as rendered by Malcolm Lyons for Penguin or Jamel Eddine Bencheikh and André Miquel for the Pléiade). Hārūn al-Rashīd and the Barmakids, including the vizier Jaʿfar, have become mythic as well as historical heroes. However, the historically-minded author of Consorts of the Caliphs is also an accountant, and the enormous prices paid (one hundred thousand gold dinars to the slave ʿArīb for her own slave Bidʿah, for example) or spent on wedding gifts (thousands of pearls and heavy candles of ambergris for Būrān) are entered admiringly into the record. Munificence of this princely order occurs in the Arabian Nights, but it is rarely bestowed by powerful women, as we see here: even women who are slaves, if in favor, can dispose of treasure as they wish. This contradiction is one of myriad social details that raise further questions about the nature of women’s subjugation in the oriental, and specifically Abbasid, past.

This volume is the sixteenth title in the Library of Arabic Literature, and a most valuable addition to an invaluable series that is revolutionizing access to the corpus for non-Arabic readers like myself as well as establishing meticulous editions for those who can read the works in the original language. Ibn al-Sāʿī’s gallery of women poets, wits, singers, chess players, teachers, benefactors, and builders (of waterways, libraries, and law schools) transcends the collective, stereotypical character of great ladies as femmes fatales, wives, mothers, or concubines; his report lifts a veil of silence and allows us to overhear the hum of lyric, argument, wit, and elegy from women’s voices in the past. Its rich retrievals will prove marvelously inspiring, both for scholarship and for other creative work. One might dream of a new opera—about ʿInān? about Faḍl? about Būrān?—to do justice to the women who sing out from Ibn al-Sāʿī’s revelatory and enjoyable archive.

Marina Warner

Oxford

Preface

Nine of us, namely the editorial board of the Library of Arabic Literature (LAL)—Julia Bray, Michael Cooperson, Philip Kennedy, Joseph Lowry, James Montgomery, Tahera Qutbuddin, Devin Stewart, and Shawkat Toowara—and LAL managing editor Chip Rossetti, intensively and collaboratively workshopped the translation of Consorts of the Caliphs over the course of three editorial meetings, two in Abu Dhabi and one in New York.3 I was tasked by the group with editing the Arabic and with putting the volume together, and Julia Bray was designated the project editor, that is, the editor from the LAL board chosen to work closely with the editor. Given her expertise, she was also asked to write the introduction.

In 2010, when we first told colleagues how LAL would work—numerous stages and levels of close editorial scrutiny, the assigning of in-house project editors to each and every volume, master classes in editing and translating, and collaborative, workshopped translations—most, if not all, were skeptical. We hope that this volume, which was produced according to these principles and norms, will help alleviate any doubts about the possibility, viability, and desirability of such an enterprise, and that it will come to be seen as one model for how things can be done and—such is our hope—done well.

Shawkat M. Toowara

Ithaca

Acknowledgments

The editorial board is grateful to the members of the collaborative academic alliance Radical Reassessment of Arabic Arts, Language, and Literature (RRAALL) for passing the Consorts of the Caliphs translation project on to the Library of Arabic Literature (LAL), and in particular to Joseph Lowry, the project’s spiritus auctor, who has been tirelessly committed to it.

We would like to thank Ian Stevens for early encouragement; Muhammet Günaydın of Istanbul University for obtaining a copy of the manuscript; and Gila Waels, along with Nora Yousif, Manal Demaghlatrous, Antoine El Khayat, and Farhana Goha, for cheerful and expert assistance in Abu Dhabi. The feedback we received from audience members at the public panel discussion “Caliphs and their Consorts: Translating Anecdotes and Poetry in Ibn al-Sāʿī’s Nisāʾ al-Khulafāʾ” in December 2012 in Abu Dhabi was immensely helpful—especially as we were reminded how important it is to translate for readers, not just for ourselves. The expert feedback of Richard Sieburth was invaluable, as were the participation of Maurice Pomerantz and Justin Stearns in an intensive translation workshop in Abu Dhabi in December 2013. Everyone at NYU Abu Dhabi and at NYU Press has been unfailingly supportive of us and of LAL.

*

I am grateful to RRAALL for nurturing in me a love of collaboration in scholarship and to Philip Kennedy for turning the fantasy of the Library of Arabic Literature into reality and including me in that fantasy/reality. I know I must have done something right for so much of my “work” now to involve spending time in the superlative company of Philip Kennedy and James Montgomery. When you add Devin Stewart, Tahera Qutbuddin, Joseph Lowry, Michael Cooperson, and Julia Bray to the mix, the company becomes unmatchable.

I must single out Julia. Not only did she save me from all manner of goofs and gaffes as I prepared the Arabic edition, and not only did her meticulous attention to every single word in this volume make it vastly superior—she also provided me with the opportunity to collaborate, on a daily basis, with a consummate scholar and a dear friend. For this I am truly grateful.

It is also an honor to work with the outstanding scholar-translator-manager-editor-gentleman Chip Rossetti, the wonderful and resourceful LAL aide and assistant editor Gemma Juan-Simó, and our magician of a digital production manager, Stuart Brown. Martin Grosch’s and Jennifer Ilius’s maps adorn the volume beautifully, and Rana Siblini, Wiam El-Tamami, Marie Deer, and Elias Saba contributed invisibly but crucially.

The Department of Near Eastern Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University continue to provide me with superb milieux in which to thrive.

As for my family—Parvine, Maryam, Asiya (and Cotomili)—they are spectacular in indulging my obsessions and provide a constant and welcome reminder of what is truly important.

Shawkat M. Toorawa

Introduction

Tāj al-Dīn ʿAlī ibn Anjab Ibn al-Sāʿī (593–674/1197–1276) was a Baghdadi man of letters and historian. As the librarian of two great law colleges, the Niẓāmiyyah and later the Munstanṣiriyyah, and a protégé of highly placed members of the regime, Ibn al-Sāʿī’ enjoyed privileged access to the ruling circles and official archives of the caliphate4 and contributed to the great cultural resurgence that took place under the last rulers of the Abbasid dynasty. This was an age of historians, and most of Ibn al-Sāʿī’s works were histories of one sort or another, but only fragments survive. The only one of his works that has come down to us complete is Consorts of the Caliphs. This too is a history insofar as it follows a rough chronological order, but in other respects it is more like a sub-genre of the biographical dictionary. It consists of brief life sketches, with no narrative interconnection, of concubines and wives of the Abbasid caliphs and, in an appendix, consorts of “viziers and military commanders.” This last section, however, is slightly muddled; it includes some concubines of caliphs and wives of two Saljūq sultans, as well as one woman who was neither;5 has a duplicate entry; and is not chronological, all of which suggests that it is a draft.6

For the later Abbasid ladies of Consorts of the Caliphs, Ibn al-Sāʿī uses his own sources and insider knowledge, but for the earlier ones, he quotes well-known literary materials, drawing especially on the supreme historian of early Abbasid court literature, Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī (284–ca. 363/897–ca. 972), author of the Book of Songs (Kitāb al-Aghānī). In this way, two quite different formats are juxtaposed in Consorts of the Caliphs: the later entries follow the obituary format of the chronicles of Ibn al-Sāʿī’s period; the earlier ones are adapted from the classical anecdote format of several centuries before, which combined narrative and verse in dramatic scenes. Many of the entries from both periods are framed by isnāds — the names of the people who originally recorded the anecdotes and of the people who then transmitted them, either by word of mouth or by reading from an authorized text. The names of Ibn al-Sāʿī’s own informants give an indication of what interested scholars and litterateurs in the Baghdad of his day. The meticulousness of the isnāds signals that Consorts of the Caliphs is a work of serious scholarship, as does the fact that Ibn al-Sāʿī’s personal informants are men of considerable standing.7

Ibn al-Sāʿī survived the Mongol sack of Baghdad in 656/1258 and lived on unmolested under Ilkhanid rule. Consorts of the Caliphs, which was written shortly before 1258,8 survives in a single late-fifteenth-century manuscript.9 This one small work is unique in affording multiple perspectives on things that have, over the centuries, been felt to be fundamental and durable in the Arabic literary and cultural imagination: the poetry of the heroines of early Abbasid culture; the mid-Abbasid casting of their careers and love lives into legend; a reimagining of the court life of the Abbasid period, along with the idealization of the court life of their own times, by Ibn al-Sāʿī and his contemporaries; and finally, the perspective of some two hundred years later in which the stories retold by Ibn al-Sāʿī were still valued, but lumped together in a single manuscript with an unrelated and unauthored miscellany of wit, wisdom, poems, and anecdotes.10

Ibn al-Sāʿī’s Life and Times: Post- and Pre-Mongol

What is it like to live through a cataclysm? When Ibn al-Sāʿī finished writing his Brief Lives of the Caliphs (Mukhtaṣar akhbār al-khulafā’) in 666/1267–68 (as he notes on the last page),11 it was as a survivor of the Mongol sack of Baghdad ten years earlier, in which the thirty-seventh and last ruling Abbasid caliph, al-Mustaʿṣim, had been killed. With al-Mustaʿṣim’s death came the end of the caliphate, an institution that had lasted more than half a millennium. Although the caliphate had shrunk by the end from an empire to a rump, the Abbasid caliphs, as descendants of the Prophet’s uncle, still claimed to be the lawful rulers of all Muslims. The late Abbasids ruled as well as reigned, asserting their claim to universal leadership by propounding an all-inclusive Sunnism and bonding with the growing groundswell of Sufism.12 Baghdad remained the intellectual and cultural capital of Arabic speakers everywhere.

After the Mongols arrived, all this changed. Egypt’s Mamluk rulers—Turkic slave soldiers—became the new Sunni standard-bearers, and Baghdad lost its role as the seat of high courtly culture. Ibn al-Sāʿī wrote Brief Lives in full consciousness of the new world order. The work dwells on the zenith of the caliphate centuries before and tells stirring tales of the great, early Abbasids, underlined by poetry. This is legendary history, cultural memory. After noting how the streets of Baghdad ran with blood after the death of al-Mustaʿṣim,13 Ibn al-Sāʿī recites an elegiac tally of the genealogy, names, and regnal titles of the whole fateful Abbasid dynasty, of whom every sixth caliph was to be murdered or deposed.14 The tailpiece of Brief Lives, by contrast, an enumeration of the world’s remaining Muslim rulers, is a prosaic political geography.15 Baghdad no longer rates a mention on the world stage. Culture is not evoked. The question that hangs unasked is: what was left to connect the past to the present?

Consorts of the Caliphs, Both Free and Slave, to give it its full title, is a kind of anticipated answer to that question. It is an essay in cultural memory written in the reign of al-Mustaʿṣim,16 but it shows no premonition of danger, even though the Mongols were already on the march. It represents the last two hundred years—the reigns of al-Muqtadī (467–87/1075–94), al-Mustaẓhir (487–512/1094–1118), al-Mustaḍīʾ (566–75/1170–80), al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh (575–622/1180–1225), al-Ẓāhir (622–23/1225–26), al-Mustanṣir (623–40/1226–42), and the beginning of the reign of al-Mustaʿṣim (640–56/1242–58)—as a golden age for the lucky citizens of Baghdad, thanks to the public benefactions of the great ladies of the caliph’s household.17 It is a miniature collection of vignettes juxtaposed with no reference to the general fabric of events, designed as a twin to Ibn al-Sāʿī’s now lost Lives of Those Gracious and Bounteous Consorts of Caliphs Who Lived to See Their Own Sons Become Caliph (Kitāb Akhbār man adrakat khilāfat waladihā min jihāt al-khulafāʾ dhawāt al-maʿrūf wa-l-ʿaṭāʾ). Using wives and concubines as the connecting thread, it yokes the current regime to the age of the early, legendary Abbasids.

Today most of Ibn al-Sāʿī’s prolific and varied output is lost, although much of it was extant as late as the eleventh/seventeenth century18 and scattered quotations survive in other authors. Scholars disagree whether Brief Lives is really by Ibn al-Sāʿī, probably because, unlike Consorts of the Caliphs and the Concise Summation of Representative and Outstanding Historical and Biographical Events, the only other surviving work indisputably attributed to him,19 it has no scholarly apparatus.20 But it is certainly the work of a Baghdadi survivor of the Mongol sack, typical of a period which produced quantities of histories of all kinds (as did Ibn al-Sāʿī himself).21 As for Ibn al-Sāʿī, he was sixty-three when Baghdad fell. Outwardly, little changed for him in the eighteen years he still had to live: his career as a librarian continued uninterrupted.22 Perhaps the real cultural rift had occurred before the arrival of the Mongols. The supposedly happy and glorious reign of al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh, “Champion of the Faith,” in which Ibn al-Sāʿī was born, was unprecedentedly totalitarian: according to one contemporary, the caliph’s spies were so efficient and the caliph himself so ruthless that a man hardly dared speak to his own wife in the privacy of his home.23 Courtly life centered on al-Nāṣir as the teacher of true doctrine and keystone of social cohesion.24 The latter-day ladies of the caliph’s household showcased by Ibn al-Sāʿī in Consorts of the Caliphs partake, in his eyes, of this godly ethos, and are public figures with political clout. On the face of it, they have nothing in common with the vulnerable aesthetes whose hothouse loves and whose music, poetry, and wit set their stamp on the early Abbasid court, and who are given far more space in Consorts of the Caliphs.25 These figures so fascinate Ibn al-Sāʿī that he stretches his book’s brief to include a life sketch of one, the famous poet ʿInān, who may not have been a caliph’s concubine.26

Consorts of the Caliphs as Abbasid Loyalism

Why was Ibn al-Sāʿī so interested in Abbasid caliphs’ wives and lovers? Why was he equally committed to the aesthetes and to the doers of good works? There are two answers. The first is that he was a fervent loyalist. About one third of all the writings ascribed to him were devoted to the Abbasids. Of the nineteen such titles listed by Muṣṭafā Jawād in the introduction to his 1962 edition of Consorts of the Caliphs, under the title Jihāt al-aʾimmah al-khulafāʾ min al-ḥarāʾir wa-l-imāʾ, the following were clearly designed to please, and as propaganda for, current members of the ruling house: Cognizance of the Virtues of the Caliphs of the House of al-ʿAbbās (al-Īnās bi-manāqib al-khulafāʾ min Banī l-ʿAbbās);27 The Flower-Filled Garden: Episodes from the Life of the Caliph al-Nāṣir (al-Rawḍ al-nāḍir fī akhbār al-imām al-Nāṣir),28 along with a life of a slave of al-Nāṣir, his commander-in-chief, Qushtimir (Nuzhat al-rāghib al-muʿtabir fī sīrat al-malik Qushtimir);29 a life of the caliph al-Mustanṣir (Iʿtibār al-mustabṣir fī sīrat al-Mustanṣir) and a collection of poems—“ropes of pearls”—in his praise, most likely composed by Ibn al-Sāʿī himself (al-Qalāʾid al-durriyyah fī l-madāʾiḥ al-Mustanṣiriyyah);30 a life of the caliph al-Mustaʿṣim (Sīrat al-Mustaʿṣim bi-llāh); and a book “about the blessed al-Mustaʿṣim’s two sons: how much was spent on them, details of their food and clothing, and the poems written in their praise” (Nuzhat al-abṣār fī akhbār ibnay al-Mustaʿṣim bi-llāh al-ʿAbbāsī).31

The caliphs were active in endowing libraries: al-Nāṣir that of the old Niẓāmiyyah Law College as well as that of the Sufi convent (ribāṭ) founded by his wife Saljūqī Khātūn,32 al-Mustanṣir that of the law college he had founded in 631/1233–34, the Mustanṣiriyyah. For grandees to add their own gifts of books was a way of ingratiating themselves with the ruler.33 Ibn al-Sāʿī was a librarian in both colleges, before and after the Mongol invasion, as already mentioned,34 so the following titles should be counted as part of his loyalist output: The High Virtues of the Teachers of the Niẓāmiyyah Law College (al-Manāqib al-ʿaliyyah li-mudarrisī l-madrasah al-Niẓāmiyyah) and The Regulations of the Mustanṣiriyyah Law College (Sharṭ al-madrasah al-Mustanṣiriyyah).35

How do the early Abbasid concubines of Consorts of the Caliphs fit into this program of glorifying the dynasty’s virtues? The first entries on them describe only their subjects’ physical and intellectual qualities. But about halfway through the book comes a pivotal entry, that on Isḥāq al-Andalusiyyah, concubine of al-Mutawakkil and mother of his son, the great regent al-Muwaffaq. When she died in 270/883, during the regency, a court poet composed a majestic elegy on her, describing her public benefactions and her private, maternal virtues, which were also public in that her son was the savior of the state.36 Ibn al-Sāʿī lets the poem speak for itself, but the reader might be expected to know that al-Muwaffaq had been engaged for years in putting down a rebellion of black plantation slaves in lower Iraq, which had caused widespread damage and panic. He finally crushed it in the year of his mother’s death.37 Contemporary loyalist readers would certainly have made a connection between this tribute to the virtuous mother of a heroic son and the elegies collected by Ibn al-Sāʿī on “the blessed consort, Lady Zumurrud,” mother of the caliph al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh (Marāthī al-jihah al-saʿīdah Zumurrud Khātūn wālidat al-khalīfah al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh).38

As Consorts of the Caliphs progresses, the theme of feminine virtue becomes more frequent. Thus Maḥbūbah, the slave of al-Mutawakkil, mourns him defiantly after his murder, at the risk of her life, and dies of grief for him.39 Ḍirār, concubine of the regent al-Muwaffaq and mother of his son, the caliph al-Muʿtaḍid, another great ruler, was “always mindful of her dependents.”40 The princess Qaṭr al-Nadā, wife of al-Muʿtaḍid, was “one of the most intelligent and regal women who ever lived”—sufficiently so to puncture the caliph’s arrogance.41 Khamrah, slave of the murdered caliph al-Muqtadir (son of al-Muʿtaḍid) and mother of al-Muqtadir’s son Prince ʿĪsā, “was always mindful of her obligations and performed many pious deeds. She was generous to the poor, to the needy, to those who petitioned her, and to noble families who had fallen on hard times”42—the kind of encomium that Ibn al-Sāʿī goes on to apply to late-Abbasid consorts. Khamrah ends the sequence of early-Abbasid concubines; after her begins a series of virtuous Saljūq princesses and late-Abbasid models of female virtue whose merits clearly redound to the honor of the dynasty as a whole—merits which in Ibn al-Sāʿī’s time, at least before the Mongols, were highly visible in the streetscape of Baghdad, in the shape of the public works and mausolea ordered by these women.43 In this, important ladies of the caliph’s household were following the example of Zubaydah, the most famous of early-Abbasid princesses, well-known to every citizen of Baghdad and indeed to every pilgrim to Mecca,44 and Ibn al-Sāʿī, in recording their piety, good works, and burial places, is following the example of his older contemporary, Ibn al-Jawzī.45 According to Jawād, Ibn al-Sāʿī means “Son of the Runner” or merchant’s errand-man; if it is not a surname taken from a distant ancestor, but instead reflects a humble background—as Jawād argues, on the basis that Ibn al-Sāʿī’s father Anjab is unknown to biographers46—then Ibn al-Sāʿī’s grateful descriptions of the later consorts’ public works may reflect the feelings of ordinary Baghdadis.

Virtue, however—loyalty or piety-based virtue that finds social expression—is not the whole reason why Ibn al-Sāʿī devotes so much space to the early-Abbasid concubines, since most of them are not virtuous at all by these standards.

The Early-Abbasid Consorts as Culture Heroines

The majority of the early-Abbasid consorts were professional poets and musicians. Ibn al-Sāʿī and his sources, which include nearly all the great names in mid-Abbasid cultural mythography,47 rate them very highly: ʿInān “was the first poet to become famous under the Abbasids and the most gifted poet of her generation”; the major (male) poets of her time came to her to be judged.48 No one “sang, played music, wrote poetry, or played chess so well” as ʿArīb.49 Faḍl al-Shāʿirah was not only one of the greatest wits of her time, but wrote better prose than any state secretary.50 Above all, they excel in the difficult art of capping verse and composing on the spur of the moment.51 Their accomplishments are essentially competitive, and it is usually men that they compete with. The competition is not only a salon game. For the male poets—free men who make their living by performing at court—losing poses a risk to their reputation and livelihood. The women who challenge them or respond to their challenge are all slaves (jāriyah is the term used for such highly trained slave women). Of the risks to a slave woman who fails to perform, or to best her challenger, only one is spelled out in Consorts of the Caliphs, in the case of ʿInān, whose owner whips her.52 On the other hand, the returns on talent and self-confidence can be great, as is seen in the case of ʿArīb, whose career continues into old age, when her verve and authority seem undiminished and she has apparently achieved a wealthy independence.53 We are shown how, between poets, the fellowship of professionalism transcends differences between male and female, free and slave. But even in the battles of wits between a jāriyah and her lover, where the stakes are very high—if she misses her step, the woman risks not just the loss of favor and position, but the loss of affection too, for many jāriyahs are depicted as being truly in love with their owners—there is often, again, a touch of something like comradeship: a woman’s ability to rise to the occasion can compel her lover’s quasi-professional admiration. We should remember that nearly all the early-Abbasid caliphs composed poetry or music themselves, and they all considered themselves highly competent judges. Though the consorts’ beauty is routinely mentioned, when we are shown a cause of attraction, it is the cleverness, aptness, or pathos of their poetry that wins over the lover. The workings of attraction and esteem can be imagined and explored in the case of slaves as they rarely are in that of free women; and this, in addition to their talents and exquisite sensibility or dashing manners, is what makes the early-Abbasid jāriyahs culture heroines, whose hold on the Arabic imagination persists through the ages.

Ibn al-Sāʿī’s Contribution

Unlike Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī, the authority most cited in Consorts of the Caliphs,54 Ibn al-Sāʿī seems far less interested in music than in poetry. He was a poet himself, as indeed was almost any contemporary Arabic speaker with any claim to literacy and social competence. He and all his readers knew the wide range of available poetic genres, both ceremonial and intimate. As children, they would have been taught the ancient and modern Arabic poetic classics, and as adults, they might have written verse on public occasions and would certainly have composed poems to entertain their friends, lampoon unpleasant colleagues, or give vent to their feelings about life. The poetry of the jāriyahs has its own place in this spectrum. It is occasional poetry: even when they write accession panegyrics or congratulations on a successful military campaign, the jāriyahs keep them short and light.55 What is poignant about their poetry is its ephemerality: it captures and belongs to the moment. And what is especially moving about it is that (in the eyes of Ibn al-Sāʿī, who simplifes but does not traduce the complex vision of Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī) it is identical with the woman who composes it and her precarious situation. As Ibn al-Sāʿī tells it, the poetry of the slave consorts is an act of personal daring and moral agency, which finds its reward in the love of the caliph and sometimes even in marriage.56 This is something considerable, contained in the small compass of the anecdote format.

There have not been many attempts, in modern scholarship, to make distinctions between the jāriyahs as poets and cultural agents, on the one hand, and as romantic heroines and objects of erotic and ethical fantasy, on the other. There are basic surveys of the sources;57 there is a pioneering study of the world of Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī’s Book of Songs;58 and, most recently, there is an exploration of the values underlying the competition between jāriyahs and free male poets and musicians.59 Medieval contemporaries were alive to the social paradox of the woman slave performer as a leader of fashion but also a commodity, an extravagance but also an investment for her owners, able to some extent to turn her status as a chattel to her own profit by manipulating her clients—and they satirized it unsympathetically.60 By comparison, modern reflection on female slavery and its place in medieval Islamic societies is unsophisticated.61 The time span of Consorts of the Caliphs is wider than that of the mid-Abbasid classics which have been the focus of modern scholarship until now, and the life stories it presents of female slaves bring together a greater range of backgrounds and situations and open up more complex perspectives.

Ibn al-Sāʿī’s special contribution to the subject is his seriousness and sympathy, the multiplicity of roles within the dynasty that he identifies for consorts, and his systematic, and challenging, idealization of the woman over the slave.

Julia Bray

Maps

| 1 | The Abbasid Caliphate |

| 2 | Early Baghdad |

| 3 | Later Baghdad |

| 4 | Later East Baghdad |

Note: The maps of Baghdad are based principally on Le Strange, Baghdad (1900), Jawād and Sūsah, Dalīl (1958), Makdisi, “Topography” (1959), Lassner, Topography (1970), and Ahola and Osti, “Baghdad.” In cases where precise locations are not known, the aim has been to give readers of Consorts an idea of the relationships between different places topographically. Outright conjectures are followed by a question mark.

The Abbasid Caliphate

Early Baghdad

Later Baghdad

Later East Baghdad

Note on the Edition

The Manuscript

There appears to be only one extant manuscript of Ibn al-Sāʿī’s Jihāt al-aʾimmah al-khulafāʾ min al-ḥarāʾir wa-l-imāʾ, which is in the Veliyyuddin Library in Istanbul, bearing MS no. Veliyyuddin 2634. Muhammet Günaydın of Istanbul University kindly obtained a copy for us on CD from the Beyazıt Devlet Kütüphanesi (Beyazıt State Library) in 2012.

The manuscript has 58 folios, the first 48 of which consist of Jihāt al-aʾimmah. Folios 49–58 comprise a miscellany of stories, some humorous, some moralistic, culled from the adab literary tradition.62 The colophon to Jihāt al-aʾimmah appears on the verso of folio 48. It states that the copying of the manuscript was completed on 4 Rajab, 900 [March 30, 1495] by one Muḥammad ibn Sālim al-Ḥāniʾ.63 It also mentions the fact that the book has been supplemented with “the consorts of princes and important viziers” (maʿa mā uḍīfa ilayh min mashhūrī [sic] jihāt al-sādat al-umarāʾ wa-l-jullah min al-wuzarāʾ). This refers to the fact that in the latter part of the book, Ibn al-Sāʿī includes entries about the consorts of a vizier and of several Saljūq sultans.

There are nine lines to each page in a legible Naskh hand. The text is in black ink. Red ink is used to indicate headings, thus the names and affiliations of the consorts; quotations, e.g. a horizontal line above the lām of (قالـــ) and other such verbs; the ends of paragraphs or subsections; and the beginnings and endings of verses. In only one place (the “Saljūqī Khātūn” heading) is the manuscript illegible, but the missing words can be divined from the entry itself. There is the occasional—and by no means untypical—omitted word that is then written in the margin. That the scribe was also hasty, or even sloppy, is evident from the fact that the tail end of one anecdote and the beginning of another pertaining to one consort is entirely misplaced in the entry about another consort, and from features such as the listing of ordinal numbers out of order, or the misnaming of famous authors. The scribe also appears not to have been very knowledgeable about the subject.64

Previous Edition

There is one previous edition of the work, published as Nisāʾ al-khulafāʾ, al-musammā Jihāt al-aʾimmah wa-l-khulafāʾ min al-ḥarāʾir wa-l-imāʾ (lit. Women of the Caliphs, known as Freeborn and Slave Consorts of the Imams and Caliphs), first published by Dār al-Maʿārif in Cairo in 1962 as volume 28 in the “Dhakhāʾir al-ʿArab” series and reprinted in 1968 and 1993.65 Manshَūrāt al-Jamal issued a handsome reprint in 2011.66 The editor, Muṣṭafā Jawād (1905–69), like Ibn al-Sāʿī a son of Baghdad, had learned of the existence of the work from the French scholar Louis Massignon (1883–1962). He obtained a photograph of the manuscript from Ahmed Ateş of Istanbul University in 1952, then produced a photostat copy on which he based his edition. Jawād’s edition includes the manuscript pagination.

Jawād had a broad and deep knowledge of Ibn al-Sāʿī and of Baghdad;67 this is reflected not only in the edition, but also in his introduction about Ibn al-Sāʿī and his times, as well as his detailed footnotes identifying places, events, individuals, and references in other works. Jawād’s occasional faulty readings can be attributed to the quality of the manuscript reproduction. He is also more at ease with the political history of the 5th–6th/11th–12th centuries than with the literary history of the 3rd–4th/9th–10th centuries. For instance, he replicates a scribal error about Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī’s uncle;68 he has Ibn Abī Ṭāhir report an event that happened after Ibn Abī Ṭāhir died; and he tries to make sense of the scribe’s (أبو جز) when it appears to be an error for (الجماز).

This Edition

In preparing this edition, I have had the benefit of access to a high-resolution full-color digital copy of the manuscript.69 This has allowed me to correct some of Jawād’s misreadings and to include material that he missed or omitted. I have also benefited greatly from Jawād’s edition and accordingly signal in the notes when I have adopted his reading or accepted a word he has interpolated to improve the sense. In keeping with LAL practice, I confine the notes to information about editorial choices. I do not provide references to other sources. Thus, in the entry on ʿArīb, for example, Jawād lists other entries and references to her in other works. The only time I do this is when Ibn al-Sāʿī himself quotes another extant work; if the work is not extant, or the quotation undiscovered, I so indicate.

The principles used in establishing the Arabic edition are as follows:

| • | I have abided by the LAL policy of minimal and crucial voweling except in poetry and the Qurʾan. Fatḥah tanwīn is provided where deemed helpful. |

| • | All consonantal shaddahs have been included. |

| • | Waṣlahs only appear on conjoined alifs (e.g. preceded by wa- or fa-), in poetry, and in speech. |

| • | The manuscript has both إصفهان \ الإصفهانيّ and إصبهان \ الإصبهانيّ. I have adopted the latter as the standard forms. |

| • | The only punctuation used are periods at the end of paragraphs/sections and the occasional clarifying colon. |

| • | I have aspired to format, paragraph, and indent consistently and in such a way as to clarify syntax and narrative sequence. Following LAL policy, I have numbered paragraphs. |

| • | The entries themselves are also numbered for ease of reference. |

| • | Following LAL policy, I do not provide in-text references to the manuscript pagination. |

| • | Although I have “corrected” such things as irregular number use (أربع دواليب), these are in fact nothing more than a standard feature of Middle Arabic or at least non-formal Arabic. Other Middle Arabic features include disappearance of case (e.g. يزيد for يزيدا); unusual plurals (e.g. غانيات); avoidance/disappearance of hamzah (e.g. المستضية); agreement with nearest antecedent (e.g. جهات الخلفاء سأتبعهم); repetition of بين; words that are usually separate being written together (e.g. فيماذا); and use of ṣād for sīn (e.g. بالمصير). These are all recorded in the notes. The only silent changes have been the “restoring” of final hamzahs, e.g. in خلفا or عطا, and of alifs, e.g. to القسم. |

| • | In the poetry, I identify only the main meter family, not the particular variant used; these appear also in the Index of Verses. I am grateful to Tahera Qutbuddin for going over these. |

| • | The sigla used in the Arabic footnotes are: م = MS Veliyeddin 2634 and ج = Jawād’s edition. |

In undertaking the edition, I benefited immeasurably from the knowledge, expertise, guidance, advice, and friendship of the project editor, Julia Bray.

Shawkat M. Toorawa

Note on the Translation

The project of translating Ibn al-Sāʿī’s Consorts of the Caliphs was first suggested by Joseph Lowry to the academic alliance Radical Reassessment of Arabic Arts, Language, and Literature (RRAALL), of which he and three other Library of Arabic Literature editors are members—Michael Cooperson, Devin Stewart, and myself, Shawkat Toorawa.70 Having successfully published a collaboratively authored book on Arabic autobiography in 2001,71 RRAALL was looking for a follow-up project. Lowry made the case that Consorts of the Caliphs captured our various and varied interests (the Abbasids, art and archaeology, ethnomusicology, gender, history, language, law, literature, the Saljūqs), that it was short, that it was divided into manageable parts, and that it was of inherent interest. By 2008, eight of us had translated consecutive portions and we had a complete if uneven working translation. In 2009, Lowry, Stewart, and I met in Philadelphia to even out the translation and subsequently dispatched it to Cooperson, who made many changes and suggestions. Then the project went quiet.

In 2009, when Philip Kennedy asked me what kinds of works I thought one might include in a “library of Arabic literature”—then still only an idea—I mentioned, among other works, Ibn al-Sāʿī’s little book. I even told him a “draft translation” was available. Later, when the Library of Arabic Literature (LAL) had become a reality, Kennedy (now the LAL’s General Editor), who hadn’t forgotten Ibn al-Sāʿī, mentioned the book to the board. In 2011, Julia Bray suggested that it was an ideal candidate for a collaborative LAL project and so, one morning in New York City, we resolved to take it on, with the blessings of RRAALL and of the LAL board. We realized—as we had been realizing and discovering with other LAL books that we had already edited—that the “draft translation,” in spite of the effort that had been put into it, was less a translation than it was an “Englished” version of the Arabic, in a prose that we have come to think of unflatteringly as “industry standard.”

Process

Our first act was to appoint a project editor from our own LAL editorial board, as we do with all our projects. We chose Julia Bray, who went through the “draft translation” and wrote a report describing what needed to be done to bring it up to LAL standard—something we require for all potential LAL projects. At the same time, we showed it to the distinguished translator Richard Sieburth. With Bray’s and Sieburth’s positive but critical feedback, we decided that it was best to start from scratch. We divided the book into five parts and assigned each part to a team of two; the ten people involved were the eight LAL board members, the managing editor, and Richard Sieburth. After our first workshop we presented our preliminary thoughts and samples of our work at a public event in Abu Dhabi. For the next workshop, we invited Justin Stearns and Maurice Pomerantz (both of New York University Abu Dhabi) to join us and we shuffled around the teams. After these teams had done their translations and conferred among themselves and with one another, I then collated their material, made the various parts consistent based on the principles and choices that we had agreed upon, and e-mailed the material to everyone to read through and ponder.

We held a final workshop during our May 2014 editorial meeting in New York City, where we projected the translation onto a screen and went through it all together, comparing it to the manuscript. At the end of three half-day sessions, we had thrashed out many issues, which involved, among other things, reversing course on certain key decisions. Then, in a final daylong session, Julia Bray (the designated project editor) and I (the designated editor of the book) spent a most genial day going through it all again line by line, establishing new principles, establishing consistency where it was not yet present, and deciding on shape and format. Julia then returned to Oxford and I to Ithaca.

I then went through the entire translation again, implementing all of our decisions, and when I was satisfied I sent it back to Julia Bray to vet carefully. I also sent it to Joseph Lowry for his feedback. After I had incorporated Joe’s feedback and intervened stylistically again myself, we sent the translation to Marina Warner, who very graciously agreed to write a foreword. Julia then sent me further detailed comments and annotations, which I addressed and incorporated, and she proceeded to write her introduction.

At that point, I set about producing fuller notes to the translation. I also prepared preliminary glossaries. LAL policy is to have one unified glossary of names, places, and terms, but in this case we felt that separate glossaries of the authorities (authors and transmitters cited) and the characters featured in the anecdotes, of place names, and of realia would be far more useful to reader and scholar alike; we also decided that we would gloss every individual in the book. As I finished each constituent part, I sent it to Julia, who went over it very carefully. We would often catch a problem, or discover a reference that we wanted to insert, on our third or fourth exchange or read-through.

Once everything—front matter, Arabic edition and notes, English translation and notes, glossaries, indices—was ready, I sent it all off to Julia, in her capacity as project editor, so that she could vet it one last time and make any final crucial interventions. Once she gave the go-ahead, an executive editor—in this case James Montgomery, who made numerous valuable suggestions—did an executive review and then gave the green light to our managing editor, Chip Rossetti, to put the book into production.

The reason I have given such a detailed description of the process is that I want to highlight the fact that this is in every way a collaborative translation, and has been from the very beginning. It is true that in the final stages, Julia and I ended up making many decisions without the input of the rest of the group, but these were generally very small and/or stylistic decisions or else instances where we realized we had misinterpreted and therefore mistranslated something. Macro-level decisions were always taken as a group, after protracted discussion. As for the front and back matter, Julia and I collaborated extensively. And as I have described above, Joseph Lowry and James Montgomery had the opportunity to weigh in again.

Principles

The first and easily most important question we faced was whether and how to translate names, designations, and titles. The second entry in the collection, for example, is devoted to “Ghādir jāriyat al-Imām al-Hādī.” “Ghādir” is a nickname or pet name meaning “treacherous” or “inconstant.” We could not initially agree whether to render the name in English or keep it in Arabic. Not to translate a nickname would be to shortchange the English reader; she could, it is true, learn from a footnote what a name means, but she might miss the fact that the name means what it means every time it is used. The group also agreed, however, that the “meaning” might constitute an undue distraction and sound odd besides. There are names that are meaningful but which one might not wish to translate; imagine a Spanish text featuring a woman named Concepción—one would likely not translate her name into the English “Conception.” We eventually decided to use Arabic names throughout. In the case of slaves, we provide a translation in quotation marks after the first occurrence (as it happens, typically in the heading), but use the Arabic name thereafter. In the case of the freeborn, however, we do not translate the name.

This decision extended to the titles of caliphs. The choice of a regnal title, whether made by the caliph himself or bestowed on him as heir apparent, was always significant and sometimes reflected a program; such is the case for al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh (husband of Saljūqī Khātūn, §29 below), who aspired to be “The Champion of the Faith,” but even though Arabic readers will be very aware of the meanings of such titles, it is not the norm to translate them. As for the title Imām preceding a caliph’s name, that is one standard way of referring to a caliph, but it was clear to us that to use the title “Imam” in English would cause confusion, whereas to use “Caliph,” as we have, would be unambiguous. We also decided that the caliphal title “Amīr al-Muʾminīn,” literally “Commander of the Faithful” and routinely used as a form of address, could sound clumsy in some contexts in English; we opted instead for “Sire” or “My lord” in many, though not all, cases.

The word jāriyah in the phrase “Ghādir jāriyat al-Imām al-Hādī” is often translated “slave girl” or “singing-girl.” While some of us thought that the demeaning aspect of the word “girl” was a positive feature of the word in this case, appropriate for describing someone who was a slave, no matter how accomplished or respected, others of us thought it would be more powerful (if that is the right word) to use “female slave” or “slave”—and this view prevailed. In the end, we settled on “slave” alone. The Ghādir heading thus reads:

Ghādir

“Inconstance”

Slave of the Caliph al-Hādī

As for the English rendering of the names of characters and transmitters in the text, we occasionally shorten long genealogies to make them less unwieldy for English readers. Names of well-known figures that appear in the text in a form unfamiliar to modern readers (which is usually an indication of how familiar Ibn al-Sāʿī himself was with them) are identified in the glossary.

Other decisions we made about the translation include the following:

| • | With a few exceptions (typically in the case of well-known figures or long genealogies), we render names the way they appear in the Arabic on first occurrence and thereafter shorten them to a standard form, e.g. Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī, al-Ṭabarī, or Thābit ibn Sinān. |

| • | We only translate a professional designation—e.g. “the trustee ʿAbd al-Wahhāb ibn ʿAlī”—when we are confident that it was the profession of the individual in question, rather than the equivalent of a modern surname. |

| • | We follow the spelling conventions of the Encyclopaedia of Islam Three. |

| • | We render Saljūq names in Arabicized forms. |

| • | In the longer isnāds—the succession or “chain” of transmitters of an anecdote or other item of information—we frequently use long dashes to separate the sources that intervene between Ibn al-Sāʿī’s own informant and the original source of the information, so as to make it easier for the reader to follow the transmission. |

| • | We routinely substitute pronouns for proper names to make the meaning clearer. Occasionally we do the opposite, expanding a pronoun, to make attribution clearer to the reader; thus in §8.8.3, where the Arabic has simply “He said that,” we render it “Here our source, Abū l-ʿAynāʾ, notes . . . ” |

| • | Because we use “Isfahan” for the city, we use “al-Iṣfahānī” for the personal name (even though we have retained the predominating “Iṣbahān” and “al-Iṣbahānī” in the Arabic, as explained in the “Note on the Edition” above). |

| • | We have striven to make the poetry rhyme when the context or verse itself required it and used devices such as half-rhyme or assonance when the meaning of the verse or anecdote depended on it. When forcing a poem to rhyme in English would have meant altering the original meaning, we have not done so. |

| • | Translations from the Qurʾan are our own. |

Note also:

| • | Though many anecdotes in Consorts of the Caliphs appear in other extant works, we do not provide cross-references (these are available in Jawād’s edition). |

| • | We italicize the poetry to make it stand out from the rest of the text. |

| • | The maps of Baghdad in some cases do not so much reflect precise locations as they do the topographical relationships between different locations. |

| • | The first three glossaries—of characters; of authorities (authors and transmitters); and of places—contain all the names that occur in Consorts of the Caliphs. We also provide a fourth glossary, of realia. |

Shawkat M. Toorawa, on behalf of the translators

Notes to the Front Matter

Foreword

| 1 | Ardener, “Belief and the Problem of Women” and “The Problem Revisited.” |

| 2 | See Ibn al-Sāʿī, Consorts of the Caliphs, §13.5 below. References to Consorts of the Caliphs hereafter referred to by the paragraph number of the entry. |

Preface

| 3 | Details of how we workshopped and translated the book can be found in the “Note on the Translation” below. |

Introduction

| 4 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 18, 20, in Ibn al-Sāʿī, Nisāʾ al-khulafāʾ . |

| 5 | The “daughter of Ṭulūn the Turk” “who married one of her dalliances” (§35). |

| 6 | See §30.5 and §§31–39 below. |

| 7 | See §10.2 and §16.2, where impressive isnāds serve in each case to introduce a two-line occasional poem. |

| 8 | See §30.4.1. |

| 9 | See “Note on the Edition” below. |

| 10 | See “Note on the Translation” below; for the text of the miscellany, see the “Book Extras” page of the website of the Library of Arabic Literature: www.libraryofarabicliterature.org. |

| 11 | Ibn al-Sāʿī, Mukhtaṣar, 142. |

| 12 | See Hartmann, “al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh”; and Hillenbrand, “al-Mustanṣir (I).” |

| 13 | Ibn al-Sāʿī, Mukhtaṣar, 127. |

| 14 | Brief Lives adopts this inaccurate periodicity for dramatic effect. In Consorts of the Caliphs, the following are mentioned as having been killed: the sixth Abbasid caliph, al-Amīn (r. 193–98/809–13) (at §11); the tenth, al-Mutawakkil (r. 232–47/847–61) (at §15.6); and the eighteenth, al-Muqtadir (r. 295–320/908–32) (at §23.1). |

| 15 | Ibn al-Sāʿī, Mukhtaṣar, 129–41. |

| 16 | See §30.4.1. |

| 17 | See §26 (Khātūn), §27 (Banafshā), §29 (Saljūqī Khātūn). ʿIṣmah Khātūn (§24) founded a law college in Isfahan; Shāhān (§30) spent huge sums with Baghdadi tradesmen, and Khātūn al-Safariyyah (§37) provisioned the pilgrim route. |

| 18 | Jawād’s bibliography gives the titles of fifty-six items. Items 1–7, 9, 12, 15, 17–24, 26, 34–37, 39, 43–46, 51, 53 and 55 are listed by the Ottoman bibliographer Ḥājjī Khalīfah (1017–67/1609–57); see Jawād, “Introduction,” 23–32, for references. |

| 19 | Ibn al-Sāʿī, al-Jāmiʿ al-mukhtaṣar. It originally went up to 1258, but of the original thirty volumes, only volume 9 (years 595–606/1199–1209) is extant; see Jawād, “Introduction,” 26, no. 21. |

| 20 | Against the attribution are Jawād, “Introduction,” 24, n. 4 and, seemingly, Lindsay, “Ibn al-Sāʿī.” Rosenthal, “Ibn al-Sāʿī,” 925, thinks it a “brief and mediocre history . . . unlikely to go back to [Ibn al-Sāʿī].” The attribution is silently accepted by Ziriklī, al-Aʿlām, 4:265, and Hartmann, “al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh.” Robinson, Islamic Historiography, 117, argues that it is an epitome composed by Ibn al-Sāʿī as part of “a large industry of popularizing history” that had been practiced for centuries. |

| 21 | Ibn al-Sāʿī wrote several histories of the caliphs, including one whose title suggests it was in verse: Naẓm manthūr al-kalām fī dhikr al-khulafāʾ al-kirām (Versified Prose: the Noble Caliphs Recalled). This was presumably meant as an aide-mémoire, verse (naẓm) being more memorable than prose (manthūr al-kalām). He wrote another “for persons of refinement” (ẓurafāʾ), Bulghat al-ẓurafāʾ ilā maʿrifat tārīkh al-khulafāʾ (Getting to Know the History of the Caliphs, for Persons of Refinement); see Jawād, “Introduction,” 32, no. 53, and 25, no. 17. Another example of his practice of recasting his own works was his commentary on the famous and difficult literary Maqāmāt (fifty picaresque episodes in rhymed prose and verse) of al-Ḥarīrī (446–516/1054–1122), which he produced in three sizes: jumbo (twenty-five volumes), medium, and abridged; see Jawād, “Introduction,” 32, no. 54, and 28, nos. 33 and 32. |

| 22 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 16–17, 19. |

| 23 | Ibn Wāṣil al-Ḥamawī (604–97/1208–98), MS of Ishfāʾ al-qulūb, f. 231, quoted by Jawād, “Introduction,” 8; see also Hartmann, “al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh,” 999, 1001. |

| 24 | Hartmann, “al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh,” 999–1002. |

| 25 | §§2–7, 9–11, 13–19, 31; see also 34, 36. |

| 26 | §3.2. |

| 27 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 25, no. 15; see also 30, no. 47: Manāqib al-khulafāʾ al-ʿAbbāsiyyīn (The Virtues of the Abbasid Caliphs). |

| 28 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 27, no. 27. |

| 29 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 31, no. 52. Ibn al-Sāʿī refers to this work in the year 596/1199–1200 in al-Jāmiʿ al-mukhtaṣar, 9:43. |

| 30 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 25, no. 12, and 29, no. 38. |

| 31 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 28, no. 29, and 31, no. 50. |

| 32 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 17, quoting al-Qifṭī (568–646/1172–1248), Tārīḫ al-ḥukamāʾ, 177. This seems to have been in addition to the library installed in Saljūqī Khātūn’s mausoleum: see §29.2.1; and §29.2.2 for the Sufi lodge which according to Ibn al-Sāʿī was built not by Saljūqī Khātūn, but by al-Nāṣir in her memory. |

| 33 | See a later source that quotes Ibn al-Sāʿī as a witness to such donations, cited by Jawād, “Introduction,” 21. |

| 34 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 18, 20. |

| 35 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 30, no. 48, and 28, no. 34. |

| 36 | §12.3. |

| 37 | On the Zanj rebellion, see Kennedy, The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates, 180–81. |

| 38 | See Jawād, “Introduction,” 29, no. 42. Zumurrud was a slave: see n. 100 in the main text below. She died in Jumada al-Thani, 599 [February, 1203], according to the sources quoted by Kaḥḥālah in his dictionary of notable women, Aʿlām al-nisāʾ, 2:39. Ibn al-Sāʿī records her death a month earlier, in Rabiʿ al-Thani, and quotes part of a long elegy by a court poet “which I have given in its entirety in Elegies on the Blessed Consort Lady Zumurrud, Mother of the Caliph al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh,” al-Jāmiʿ al-mukhtaṣar, 9:102, 279. |

| 39 | §15.6. |

| 40 | §21.1. |

| 41 | §22.1–2. |

| 42 | §23.3. |

| 43 | See the maps immediately following this introduction. |

| 44 | Zubaydah, the wife of Hārūn al-Rashīd, was famous for provisioning the pilgrim route with wells and resting places. |

| 45 | Under the caliph al-Muqtafī (530–55/1136–60), Abū l-Faraj ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAlī ibn al-Jawzī (ca. 511–97/1116–1201), head of two, then five, Baghdad madrasahs, enjoyed an “extraordinary career as a preacher . . . through his influence on the masses, he was politically important for those caliphs who, in their struggle with the military and the Saljūqs, followed a Ḥanbalī-Sunnī orientation. Diminishing influence under other caliphs was due to different policies adopted by them” (Seidensticker, “Ibn al-Jawzī,” 338). In his history, al-Muntaẓam fī tārīkh al-mulūk wa-l-umam, “Ibn al-Jawzī . . . several times uses the obituary sections of his regnal annals to highlight the virtues of the mothers or consorts of caliphs. It seems likely that this device serves to redeem the reigns of caliphs who are not themselves wholly satisfactory from Ibn al-Jawzī’s viewpoint, and that it is meant to suggest a continuity of virtue in the Abbasid caliphate as a political institution” (Bray, “A Caliph and His Public Relations,” 36). Ibn al-Jawzī records the funerals or burials of notables, especially women, in considerable detail; so too does Ibn al-Sāʿī in Consorts of the Caliphs: see §21.2, §22.3, §23.2, §24.1, §25.2, §27.4, §28.1, §29.2.1, §29.2.2, §29.3, §32.1 and §33.1. One of Ibn al-Sāʿī’s works was devoted to cemeteries and shrines: al-Maqābir al-mashhūrah wa-l-mashāhid al-mazūrah; it has recently been edited. The work is referred to by Diem and Schöller in The Living and the Dead in Islam, 2:312, but they do not cite Consorts of the Caliphs. |

| 46 | Jawād, “Introduction,” 12. |

| 47 | Ibn al-Sāʿī’s sources for the early- to mid-Abbasid consorts include Abū l-ʿAynāʾ, Abū Bakr al-Ṣūlī, Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī, ʿAlī ibn Yaḥyā the astromancer, Hilāl ibn al-Muḥassin the Sabian, Ibn al-Muʿtazz, Jaʿfar ibn Qudāmah, al-Jahshiyārī, Jaḥẓah, members of the al-Mawṣilī family, al-Ṭabarī, Thābit ibn Sinān, and Thaʿlab; for all of these, see the glossaries. |

| 48 | §3.3. |

| 49 | §6.4. |

| 50 | §13.1, §13.7. |

| 51 | §3.1: ʿInān; §6.5: ʿArīb; §6.7: an anonymous slave; §7.3: Bidʿah; §13.3; §13.5; §13.6; §13.9; §14.2: Faḍl; §15.3; §15.4; §15.5; §15.6: Maḥbūbah; §19.2; §19.3: Nabt. |

| 52 | §3.5; §3.7. |

| 53 | §6.5. |

| 54 | Ibn al-Sāʿī cites Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī as the author of the Book of Songs, but Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī also wrote a book devoted to women slave poets, al-Imāʾ al-shawāʿir, extant and available in two editions, both from 1983, one edited by al-Qaysī and al-Sāmarrāʾī (paginated), the other edited by al-ʿAṭiyyah (numbered). The texts of the two editions are not identical, but of our “consorts,” both have: ʿInān (pages 23–44/number 1); Faḍl (49–71/no. 3); Haylānah (95–96/no. 14); ʿArīb (99–112/no. 16); Maḥbūbah (117–20/no. 20); Banān (121–22/no. 21); Nabt (129–31/no. 25); Bidʿah (139–141/no. 29). These references are given here because al-Imāʾ al-shawāʿir is not among the otherwise comprehensive list of sources cited in Jawād’s footnotes to Jihāt al-aʾimmah. (For a more recent edition of al-Iṣfahānī’s book, titled Riyy al-ẓamā fī-man qāla al-shiʿr fī l-imā, see Primary Sources in the bibliography.) |

| 55 | §13.4; §7.3; §7.4. |

| 56 | According to Ibn al-Sāʿī, Hārūn al-Rashīd married Ghādir (§2.1); we find the identical story in Ibn al-Jawzī, al-Muntaẓam, 8: 349, but al-Ṭabarī does not list her among Hārūn’s wives (The ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in Equilibrium, 326–27). Farīdah the Younger is said to have married al-Mutawakkil (§18.3); in the Book of Songs, in the joint entry on Farīdah the Elder and Farīdah the Younger, Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī (Kitāb al-Aghānī, 3:183), cites al-Ṣūlī as the authority for this; again, the “marriage” is not mentioned elsewhere. There is a question mark over these stories: the jurists would certainly have disapproved of a free man marrying a slave without first freeing her, but perhaps manumission is implied by the very word “marriage.” Two other such women are said to have married free men: Farīdah the Elder marries twice, again with no mention of manumission (§11.1); and Sarīrah—who had borne her owner a child and thereby gained her freedom when he was killed—marries a Hamdanid prince (§36.1). |

| 57 | In addition to Jawād’s footnotes to Nisāʾ al-khulafāʾ, see Stigelbauer, Die Sängerinnen am Abbasidenhof um die Zeit des Kalifen al-Mutawakkil; and Al-Heitty, The Role of the Poetess at the Abbāsid Court (132–247 A.H./750–861 A.D.). |

| 58 | Kilpatrick, Making the Great Book of Songs. |

| 59 | Imhof, “Traditio vel Aemulatio? The Singing Contest of Sāmarrā.” |

| 60 | Al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 255/868), Risālat al-Qiyān/The Epistle on Singing-Girls; al-Washshāʾ (d. 325/936), Kitāb al-Muwashshā, also known as al-Ẓarf wa-l-ẓurafāʾ, chapter 20. German and Spanish translations, as well as a partial French one, exist of Kitāb al-Muwashshā: Das Buch des buntbestickten Kleids, ed. Bellmann; El libro del brocado, ed. Garulo; Le livre de brocart, ed. Bouhlal. |

| 61 | Ali, Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam, is an important departure. |

Note on the Edition