Читать книгу Love's Orphan - Ildiko Scott - Страница 3

ОглавлениеLove’s Orphan

My Journey of Hope and Faith

Ildiko Scott

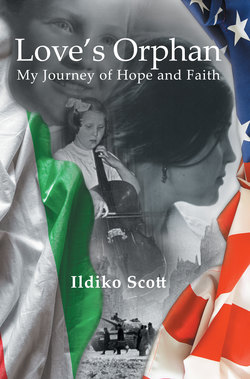

Love’s Orphan

My Journey of Hope and Faith

Ildiko Scott

Love's Orphan: My Journey of Hope and Faith

Copyright © 2016 by Ildiko Scott

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means without written

permission from the publisher and author.

Additional copies may be ordered from the publisher for

educational, business, promotional or premium use.

For information, contact ALIVE Book Publishing at:

alivebookpublishing.com, or call (925) 837-7303.

Book Design by Alex Johnson

ISBN 13

Hardcover: 978-1-63132-026-2

Paperback: 978-1-63132-030-9

ISBN 10

Hardcover: 1-63132-026-4

paperback: 1-63132-030-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930463

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

is available upon request.

First Edition

Published in the United States of America by

ALIVE Book Publishing and ALIVE Publishing Group,

imprints of Advanced Publishing LLC

3200 A Danville Blvd., Suite 204, Alamo, California 94507

alivebookpublishing.com

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Foreword..........................................................................................9

Prologue..........................................................................................11

1. My Father......................................................................................15 2. My Mother....................................................................................29

3. My Childhood..............................................................................45

4. The Orphanage.............................................................................59

5. The Revolution..............................................................................73

6. The Occupation.............................................................................91

7. Hard Years...................................................................................101

8. Young Love ..................................................................................117

9. Leaving Hungary.......................................................................125

10. America........................................................................................133

11. High School .................................................................................149

12. University Girl.............................................................................167

13. Back to Hungary.........................................................................177

14. Jud.................................................................................................185

15. True Love.....................................................................................199

16. Our Big Day................................................................................215

17. Career Years.................................................................................233

18. Our Family..................................................................................251

19. Faith and Hope...........................................................................259

Epilogue.......................................................................................273

Acknowledgments........................................................................277

Foreword

One early spring evening, I was driving home from work just as the sun was setting behind Mount Diablo in northern California. The sky was coral-red with contrasting puffy gray clouds, and the hills were vivid green and smelling fresh from the winter rains. I couldn’t help but say a simple prayer of thanks to God for all this beauty around me. As I drove into our beautiful and peaceful neighborhood I gave thanks, as I always do, for my many blessings, for my wonderful husband, for our amazing children, for our many special friends, and for all the opportunities I have been given in this great country called the United Sates of America.

How did I get here? Where did the master plan for my life come from? I do believe there is a plan for everyone’s life and that we follow the path set out for us. While I know all this I am still in awe of the fact that I am here and in America against all odds. Though I know I will never lose my Hungarian roots, I also know that the day I became an American citizen in 1971—when I pledged allegiance to the flag of this country—America became my homeland. It was a long road, but it has been worth it every step of the way.

I have often wondered if I should write about my long journey from Hungary to America. I would think, Who wants to read another life story? Doesn’t everyone have a story to tell? Though I resisted for many years writing about my life, the supportive prompting of many of my acquaintances, my friends, and most important my husband and children, helped me decide to write my story.

Though some of this now seems so long ago, from another time and place, I still believe it is a story that will inspire people. It is a story of survival and hope. It is a story of overcoming rejection, pain, and loneliness as a child. It is a story about finding faith in God.

It is my hope that as you read this book you will find that you can also change your destiny in spite of the current circumstances you find yourself in. You can let go of the pain and forgive everyone who hurt you. You can be free to become the person God intends you to be.

I would like to thank my husband, Jud, who encouraged me for so many years to write my story. I also would like to thank our son, Nathan, and our daughter, Lauren, because they convinced me that my story would be a legacy they could pass on to their children. After all, this is their story too!

Prologue

We visited Hungary, the country of my birth, with our children the summer before my mother got sick. Nathan was six and Lauren was almost three. The first thing I wanted to do was return to the orphanage to have a picture taken at the back of the courtyard where I used to sit by the iron fence and dream of freedom; where I would look outside and wonder what life would be like if I ever got out of there.

I spent some of the loneliest times of my life at this orphanage, and my “special” spot by the fence had taken on deep significance in my memory and heart. I would sit there hoping, nearly always in vain, that my mother would come see me. I would watch families walking by, parents holding the hands of their children, laughing, smiling, and loving each other with such natural ease. Wow, I thought; what is that like?

And there I was once more, this time with my loving husband, Jud, and our beautiful family. Never in my wildest dreams could I have imagined the turns my life would take, and that it would bring me so far from these humble, and often very sad, beginnings.

Being born in 1947, I arrived in the middle of a very tragic and difficult century for Hungary, and my childhood and early teen years seem now a mirror for the struggles of our people during that era. My life then, as with my former country, was trapped amid opposing forces and torn between conflicting ideologies against a backdrop of debilitating loss.

World War I had been devastating to Hungary, which had entered the conflict as part of the sturdy Austro-Hungarian Empire. Its wealth gone, economy ruined, and regional power shattered, Hungary lost more than half of its population and 70 percent of its territory. The Great Depression consequently hit the country very hard, and reliance on trade with Germany (and Italy) to stay afloat during those hardscrabble years precipitated an alliance with the Axis powers during World War II.

Hungary did its best to protect Jewish citizens from deportation during the early years of the war, but in 1944 Germany (after learning that Hungary was secretly negotiating a separate peace with the United States and Britain) occupied the country and began sending Jews to concentration camps in massive numbers. By the end of the war, in addition to the deaths of nearly one million Hungarian soldiers and citizens, more than half a million Hungarian Jews had lost their lives in the Holocaust. According to the Holocaust Memorial Center, approximately one-third of all Jews killed at Auschwitz were Hungarian. Many of my relatives lost their lives in this death camp, my father being the only one of his immediate family to survive its horrors.

Then the Soviets occupied Hungary and established a communist dictatorship. I came into the world at a time (only two years after the end of the war) of immense sadness, widespread poverty, political repression, and cultural confusion. There seemed to be tension everywhere: between Hungarians and Soviets, between “old” Europe and “new” America, between Jews and Roman Catholics. In terms of religion, the enforced communist doctrine of nonbelief attempted to supplant our Christian faith or Jewish orthodoxy. Our loyalties and traditions, indeed our very beliefs, were pushed and pulled in every direction.

These struggles were personified for me, as a young girl, in the tension between my father and mother. Their turbulent relationship and subsequent divorce, so indicative of the instability of the times, precipitated my being sent to the orphanage, where I spent most of the following ten years. For me, the reunion of my parents was the outcome I prayed for the most, as if the anxiety and confusion I sensed everywhere in the culture would be resolved through that one act of love and understanding.

The orphanage seemed like such an enormous and formidable place to me when I was a child. In 1991, when I took my family there, it seemed calm and safe, even quaint. Seen in light of the history of conflicts Hungary had endured, the orphanage seemed to me a symbol of quiet strength, formidable resolve, and protective energy. It was from another time, but the fact that it was still there, still functioning, still providing food, shelter, and education to children without home and family, gave me an immense sense of pride and well-being.

Ironically, the Soviet occupation had recently ended; in fact, the last of the Russian troops had finally left the country only weeks before we arrived in June 1991. Hungary, after decades bouncing between monarchies and fascist or communist dictatorships, was finally emerging as a democratic nation run by a parliament. Freedom, so scarce and fragile during my childhood, had returned to Hungary, and it moved me to my core.

As it was July when we visited Budapest, the orphanage was closed and all the kids were in foster homes for the summer break. We just walked into the courtyard, and I guided the children while Jud got his camera ready. My heart was beating fast as I sat on the stone base of the iron fence, holding Lauren in my lap and hugging Nathan standing next to me. For a moment it truly felt like a dream. I looked at my husband while he took our picture, and he was crying right along with me. These were happy tears we were sharing; tears of vindication and deep gratitude.

Alive Book Publishing

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my father

whose strong will, perseverance and love of America

set the path for me to follow in his footsteps.

For all these qualities, I am forever grateful.

Thank you

Ildiko

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

My Father

Tibor Kalman, my father, was born on June 4, 1913, in Esperjes, Hungary, to a very prominent Orthodox Jewish family. They moved to Miskolc for better business opportunities when Dad was four years old, and their hard work paid off. By the time he started school they owned the first and only vinegar factory in Miskolc, along with a chain of photo shops, the first of their kind in Hungary.

Miskolc was an industrial city at the time of my father’s birth. Though it wasn’t a battleground during World War I, many of its young men were killed fighting in the war, and a large number of civilians also died during that time from a debilitating cholera epidemic. The city suffered serious damage during the final months of World War II, and the postwar years were difficult, but Miskolc maintained its status as the industrial center of northeastern Hungary. These days, Miskolc has established itself as a cultural center as well, sporting many annual art and music events, including the International Opera Festival of Miskolc, which is also known as the Bartók + Opera Festival in honor of Hungary’s renowned twentieth-century composer Béla Bartók.

Dad was the youngest of three children. The oldest was my uncle, Odon, who became a successful doctor of internal medicine and also played the violin. Aunt Irene, the middle child, married a doctor and stayed home to raise her two children even though she had a university education. She was a wonderful pianist as well. Dad was the baby of the family, and the most gifted of the three when it came to music. He started playing cello at age five and excelled from the beginning. It was clear to everyone that my father’s future was in music, and they made sure that he received the best musical education possible. Initially, Dad took private lessons; later he studied cello in Budapest and graduated from the Royal Franz Liszt Music Academy and the Vienna Music Conservatory.

My grandfather, Izso Kalman, was also a gifted violin player, and he was my father’s biggest fan. They were very close. Grandfather Izso taught my father how to sing and harmonize, which the whole family did on many an occasion from the time Dad was very young. My grandmother, Elaine, was a very smart businesswoman, and she basically ran the family business.

My father had an ideal childhood in the city of Miskolc. His family gave him much love and support, and his musical career took off. He performed with the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra, under such famous conductors as Bruno Walters and Otto Klemperer; and his string quartet performed in Vienna, Austria, and Venice, Italy, as well as numerous venues in Budapest. Life was good. He was a very handsome young man and enjoyed dating young women, who were only too eager to be by his side. But Dad was really married to his cello, and was relentless in pursuing his dream to become a concert cellist.

I loved listening to his stories about practicing his cello eight to ten hours a day (and often much longer when he was getting ready for a concert). He told me that Grandfather would pull up his chair and sit there to watch him practice for hours, just to show his support. Grandmother would often come in to check on him, bringing treats. She would massage his fingers, sore from practicing so many hours. Music played a very important role in the Kalman family, and they spent many evenings singing together and having family concerts.

These precious memories of his loving family gave my father the will to survive the horrors of the Holocaust just a few years later. Nobody could have predicted how much everything would change when Hitler came to power in the early 1930s. The persecution of the Jewish people began in Germany but soon spread to both eastern and western Europe. Hitler, as we know, was determined to wipe out all the Jews, and eventually everyone else he didn’t consider a member of the “superior” Aryan race.

Hungary was basically powerless to resist Germany’s influence during World War II. Her close proximity and dependence on

German trade all but ensured Hungary would become aligned with the Axis powers. And at first there were benefits, such as newly negotiated territorial borders and financial assistance that helped the country recover from the Great Depression. Under economic and political pressure, Hungary officially joined in alliance with Germany in 1940, and we participated in the invasions of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.

While fighting the Soviets and suffering increasing losses, Hungary began secret peace negotiations with America and the Allied powers. When Germany became aware of this, they occupied Hungary and began deporting Hungarian Jews by the thousands to concentration camps in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. In spite of this, and the horror stories people soon heard, many of the Jews in Hungary really didn’t believe that they would be taken to these camps. But life for Jews in Hungary became increasingly difficult. Everyone had to wear the Star of David on their arm and all businesses with Jewish proprietors were closely monitored. Still, many people remained in denial and continued to conduct their lives as if things were normal.

Auschwitz has become an international symbol of the horrors of the Holocaust; for me and my father it was the place where our relatives were murdered by ruthless anti-Semites. In 1935, after the enactment of the Nuremberg Laws, German Jews were stripped of their citizenship because they didn’t share “Germanic or related” blood, and this discrimination escalated into a systematic attempt to eradicate the Jewish race, a policy that was formalized at the Wannsee Conference in 1942. After the Germans occupied Hungary in 1944, Hungarian Jews were deported en masse to the Auschwitz camp, where most perished in the gas chambers.

According to the selection process at the camp, anyone deemed not “fit for work” was immediately put to death, while those that could perform physical labor were sent to nearby labor camps, where they were worked until, in most cases, they literally dropped dead from starvation and fatigue. More Hungarian Jews died at Auschwitz than any other group, with an approximate loss of 438,000. The next-largest group was Polish Jews, of whom 300,000 lost their lives in the camp. It is estimated that one in six Jews murdered in the Holocaust died at Auschwitz.

My grandfather, Izso, died in June 1944, right before my father and his family were taken to this hellish death camp. The men and women were separated, and the children were taken away from their parents. My father was put to work in a labor camp, in Galicia near the Hungarian-Polish border. But the rest of his family was taken straight to the gas chambers. He never saw or heard from them ever again, and didn’t find out how they died until after the war was over.

Life in the labor camp was brutal. Prisoners were forced to build railroads in the Hungarian countryside not far from the gas chambers. The only positive thing was that some of my father’s former colleagues from the string quartet ended up in the same camp with him. Occasionally they were required to perform at night for the German officers and guards, who craved entertainment. Germans were known for their love of classical music, and, as luck would have it, Dad’s gift of playing the cello helped him (and his fellow musicians) receive slightly better treatment than the rest of the men in the camp. Eventually it played a role in their escape from the camp a few months later.

When the Germans began losing the war—after the United States joined the Allies—things got increasingly disorganized and chaotic in the camp. The German soldiers routinely got drunk every night. There were constant changes in leadership as people were either moved to different posts or ran off, afraid of what might happen to them after the war. They knew that once everyone found out about the atrocities commited upon hundreds of thousands of innocent people, they would be held accountable.

One night, after Dad and his buddies had finished playing their obligatory concert for the intoxicated Germans, many of the guards fell asleep and others just left the camp. This was my father’s big chance to escape, and he and the other musicians sneaked out of the camp in the middle of the night.

By this time, in the early days of 1945, the Russians were advancing into eastern Europe as the American troops swept in from the west. My dad and his three friends just kept on walking trying to get as far away from the camp as possible. The second day of their long walk there were shots fired around them, and they ran into an abandoned farmhouse to hide—after all, they were escaped Jewish prisoners and had no idea who was firing the shots.

Then there was a big explosion as an artillery shell hit the house. Dad was injured badly and his right arm was nearly severed by the shrapnel. When he regained consciousness, he was being carried on a wagon covered in blood and suffering excruciating pain in his right arm. The Soviet soldiers eventually brought him to a vacant church that had been turned into a makeshift emergency center. Their doctor explained to my father that he was losing too much blood, and for him to survive they needed to amputate his right arm to stop the bleeding. The last thing he remembered was the unbearable pain as his arm was cut off just below the shoulder. He remained unconscious for days after. He was thirty-one years old.

The next few months were a nightmare as Dad went through a slow and painful recovery in a local hospital. After he was well enough to be discharged, he made his way back to Miskolc, where he learned that none of his immediate family had survived the concentration camp in Auschwitz. He was now completely alone, with one arm, his beloved family gone, and his life-long dream of being a concert cellist shattered with the loss of his arm.

After the war was officially over, the Soviet Army occupied Hungary along with most of Eastern Europe For several years after the war, the Soviets used political pressure to ensure that communists would be the governing majority in the Soviet Union’s neighboring Eastern European countries. In February 1946 the Hungarian monarchy was officially abolished and replaced with the Soviet-controlled Republic of Hungary. After the mutual assistance treaty between Russia and Hungary in 1949, Soviet troops in Hungary became a mainstay until the fall of the Soviet empire in 1991.

When Dad returned to Miskolc, he found the family home destroyed, the vinegar factory bombed out and badly damaged, and most of the photo shops in ruins. The family fortune had been buried in Miskolc. This was a common practice among the Jewish people when the persecution began. They were trying to protect their assets for family members so they could rebuild their lives in the event they were lucky enough to survive the Holocaust. My father used this money (and sold the family’s jewelry) to pay the costs of rebuilding the vinegar factory.

My father had a distant aunt who was, like him, the only survivor of her immediate family from the Holocaust. She owned a very small grocery store in Miskolc, and Dad stayed with her while he rebuilt the vinegar factory, the family home, and his personal life.

One day Dad went to his aunt’s store to pick up some groceries. When he was paying for the food he saw a beautiful young girl in her teens at the cash register. The rest, as they say, was history. Gabriella Molnar was a stunning young beauty and Dad was a very handsome man in his prime. It was love at first sight for both of them. The pretty young lady would soon become Dad’s wife and my mother.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 1

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 1

The famous trio performed all over the country and Europe.

New Trio Image

Formal photo of my father when he began performing as a solo

cellist with the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra circa 1938.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Last picture of my father with two arms immediately after arriving at the labor camp. He is smiling for the camera, not really knowing what to expect.

Formal photo of my father when he began performing as a solo cellist with the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra circa 1938.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

The back side of the tombstone shows the list of the names of my father’s family killed in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

The tombstone of my paternal grandfather; the only member of the Kalman family who passed away right before the family was taken to the gas chambers. Our son, Nathan, is in the foreground.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Fred Balazs and my father: A lifetime of unbreakable friendship.

Last picture of my father with two arms immediately after arriving to labor camp. He is smiling, not really knowing what to expect.

Fred Balazs and my Father: a life time of unbreakable friendship.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

My Mother

Gabriella Molnar, my mother, was born on March 18, 1929 in Debrecen, Hungary. She was the third child out of six. When she was born her parents already had two girls, and soon after her, they had two boys and another girl. Mom never had anything new, only hand-me-downs from her two older sisters. She was closest with the firstborn, Aranyka, and oddly enough both of them married much older men and then divorced, and then married twice more. They also shared the similar trait that their lives were primarily focused on men. It seemed they were unable to live their lives alone.

Mom’s birth seemed a prophecy of hard times to come. My grandmother was on her way home from the outdoor village market when she could tell that her baby was coming and there was no stopping it. Grandfather was at work, but fortunately the two older girls, Aranyka and Mandi, were there to help. They were close to the famous Nine Arch bridge when my grandmother could not go any farther, and she lay down under one of the arches where there was shade and some privacy. It was not an easy birth, but it was quick. At that point some good-hearted women came with my two young aunts, and they cut the cord and wrapped my mother in some warm towels. Then somebody came back with a wagon to take grandmother home. The next day, the village doctor paid her a visit, but she was already up taking care of her family. Grandmother used to say that the birth was just the forewarning that there wasn’t going to be anything easy about raising my mother.

I know Mom got into trouble a lot for not minding, or not telling the truth, or just generally misbehaving. Grandmother always had to be there to rescue her, and the other children often felt that Mom got more attention than they did. It sometimes makes me think of the story of the Prodigal Son in the Bible, who caused so much heartache and pain for his father, yet was still loved and welcomed home regardless of what he had done in the past.

My grandmother, Margit Jassinger, came from a very poor Orthodox Jewish family in Debrecen, Hungary. There she met my grandfather, Miklos Molnar, who was a university graduate and an engineer by profession. He came from a very prominent Roman Catholic Family. Their worlds could not have been more different, but as they say, love is blind and nothing could come between them. They fell in love, and then broke with tradition by getting married without the approval of their families. In the early 1900 it was simply unheard of for an orthodox Jewish girl to date or be even in the same room with a man of Roman Catholic faith

While there had always been a tenuous relationship between Jews and Christians in Europe, the divide grew to its most dangerous level during the twentieth century. “Blood libel” accusations (the baseless claim that Jews were murdering Christians and using their blood in religious rituals) led to the immigration of approximately 175,000 European Jews to America in the mid-twentieth century. Unfortunately, anti-Semitism was also peaking in the United States during these years, with prominent American heroes like Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh openly supporting fascism and espousing the moral inferiority of the Jewish race. It was even worse, though, in Europe, and the rise of the Nazism brought the hatred between Christians and Jews to a fever pitch.

During these years in Hungary, it was unacceptable that an Orthodox Jewish girl with only an eighth-grade education would marry a well-educated, well-to-do Roman Catholic gentleman. Both were immediately disowned, and they never saw or heard from their parents again. I could never get my grandparents to talk about their parents or the families they had lost.

My grandmother converted to Catholicism long before the war, and my grandfather’s family was Roman Catholic going back several generations. Since she had had no contact with her family for so many years and had become such a devout Christian, nobody knew of her Jewish background. This likely saved her life during the Holocaust.

For the first five years of their marriage, Grandma and Grandpa didn’t have children. Grandmother started attending church with Grandpa on Sundays but didn’t convert to Christianity at that time. Then, one night, she had a very unusual dream. Here is how she told it to me:

One Sunday we did what we always do; we went to church, and then I was preparing our noon dinner. It was a quiet, ordinary day. I had been feeling something stirring inside of me after years of attending the Catholic Church services. I began to question my Jewish faith, and I wanted to know more about this Jesus person whom the Christians worshipped and the Jewish people denied. Your grandpa and I had long talks about our faiths, but he never pushed me to convert. He was waiting patiently for me to come around.

That particular Sunday night we went to bed and I had the most unusual dream, one as real as anything I ever experienced. In the dream, I was on my way home from our church and it was a very stormy night. I got so lost and I just could not find my way home. It was completely dark and all I could think about was my children waiting for me at home with Grandpa probably worrying about my whereabouts. The more I tried to find my way home, the more lost I got.

I was frantic with fear and the rain was coming down very hard. I was soaking wet, my feet sinking in the muddy road, which slowed me down and made me even more desperate. In my exhausted state, I finally just dropped down on my knees and cried out to Jesus for his help! I vaguely remember saying something like, ‘Jesus, if you really exist, please take my hand and help me to get home!’ I was sobbing so hard that I thought I was going to die. And then out of nowhere there was this soft light coming from behind me, and in that moment I knew that somehow I was going to be okay. Jesus had heard my plea! I was afraid to turn my head around, but felt a hand touch me and lift me up out of the mud. When I looked up, I saw our house with the lights on right ahead of me, and I just walked straight toward our door.

Grandpa was already standing at the door, waiting for me anxiously. I planned to tell him everything that happened to me after I cleaned off all the dirt and mud that covered me from the storm. When I looked down I could not believe my eyes. I was completely clean and dry and there was not a speck of mud or dirt anywhere on me.

I woke up in the middle of the night completely soaked with sweat, and I cried like a baby. Grandpa woke up quite concerned, thinking I must be ill, but I finally calmed down and slowly started telling him about my extraordinary dream. He held me in his arms for a very long time, and during that night I made the decision to convert to Catholicism and give my heart to Jesus. Then I fell into the deepest and most peaceful sleep. The next Sunday I became a Christian and never looked back. Three months later I became pregnant with our first child, Aranyka, and as you know we had five more children after that: Mandika, Gabriella (my mom), Imre, Klarika, and Bela.

A few months after I became a Christian, something else happened that was very unusual. We came home from church, and I was about to start preparing our Sunday noon dinner, but I got this sudden urge to leave the house. I felt I was supposed to go somewhere, so I just picked up my purse and took off. Grandpa was completely perplexed, and decided to follow me. He must have thought that I’d lost my mind! I remember stopping at some house not too far from our home, and without knocking I opened the front door. I saw about a dozen or so people sitting in a circle, and there was an empty chair in the middle of the circle. Then everything went blank for me.

When I came to, I was sitting in the middle of the room in that chair looking at all these people I didn’t know. They asked me who I was and where I came from, and I asked them the same thing. It was a relief to see Grandpa standing by the door, but he was as confused as I was, trying to figure out what had just happened. Apparently, this group of Christians had been meeting there every Sunday after church for some time, believing that God/Jesus would send them a spiritual leader. We started meeting with this small group after church every Sunday. Grandfather, who knew how to write shorthand, kept a pretty good record of what was I was saying while I was seemingly asleep in a trance. There was so much I still didn’t understand, but I knew that I was just an instrument of our Lord and if what I do helps people, then so be it. I just had to follow the path that God had set before me.

My mother always seemed to be struggling while she was growing up. From what I was able to gather from aunts and uncles back home, she was likely sexually abused as a child, either by my grandfather, or, more likely, some friends of the family. It also could have been somebody in the church, perhaps one of the priests. I base this on overhearing some verbal exchanges between my grandmother and grandfather, in which they discussed my mother’s lack of willpower (as well as that of Mom’s older sister) when it came to resisting the attentions they received from the opposite sex. They were also talking a lot about how they would have to watch out for all the girls in the family and keep them away from some of the clergy in their church. Knowing my grandparents’ moral values, I suspect it was someone who was close to the family who molested Mom. I have no other explanation for her behavior regarding her constant need to be with men. As I understand it, this kind of behavior is not unusual for a girl who has been molested as a child. When Mother was growing up, nobody talked about it. Adults had a lot of authority over children, and if you tried to speak up, nobody would have believed you anyway.

It was also hard on my mother’s family during the war, especially with four young girls. Rape was very widespread during the World War II years, and was not even considered a serious crime by the Soviet or German military. Of course, Jewish women were particularly vulnerable during the reign of Hitler, and in fact, if a German soldier was found guilty of raping a Jewish woman he would be reprimanded for mixing the races, which was strictly forbidden, but not for the rape itself. For both the German and Soviet armies, rape was used as a weapon of war, and Hungarian women were constantly in danger. It is estimated that the Red Army alone raped upward of two million women over the course of the war and its aftermath, mostly in Eastern Europe and Germany.

Knowing that the Russian and German soldiers were committing these crimes routinely, and with girls as young as twelve, my grandmother would smear shoe polish on her daughters’ faces and dressed them in baggy clothes so they would hopefully be ignored. Grandmother told me there were a couple close calls, but with God’s grace they were spared that horror. She said the Soviet soldiers just looked so young, and often she would feed them because they were cold and hungry. She prayed that would shift their attention away from going after her girls.

Mom never finished high school, but some of her more sophisticated and well-educated male friends exposed her to literature, the arts, and (thanks to my father) classical music, opera, and ballet. As an adult she was closest with my uncle Imre, who had a doctorate in literature and became a poet laureate in Hungary. Imre taught my mother poetry and exposed her to classic writers like Arthur Miller, Thomas Mann, Anton Chekhov, Steinbeck and Hemingway. Imre and Mom also enjoyed the nightlife in Budapest, and Mom particularly loved to be around members of Imre’s famous literary circle.

She had a good heart, but that quality often got her into trouble. I remember a story my grandmother told me. My grandfather had gotten a big promotion as an engineer for the railroad, and to celebrate he had a brand new pair of shoes made. One afternoon as a child, Mom was home alone and a beggar knocked on the door asking for food. He was barefoot and it was winter, and Mom felt so sorry for him that she ran into the bedroom, grabbed grandpa’s brand new shoes, and gave them to this poor man. Needless to say, she received a very memorable spanking when my grandfather came home.

My parents were married in the spring of 1946. Dad was thirty-one and Mom was only sixteen. He was a well-educated and well-traveled man, while she was only in her second year of high school. I don’t think either of them realized at the time the obstacles they would face because of their age differences and different family and religious backgrounds. Dad was raised in an Orthodox Jewish family and Mom was baptized Roman Catholic.

The marriage was complicated from the beginning. Dad wanted a family right away, but Mom didn’t want children at all. Nevertheless, she got pregnant soon after they married, and I was born on April 24, 1947 in Miskolc, Hungary. This was two months before her due date and one month after her eighteenth birthday.

Dad was busy rebuilding the vinegar factory, and he moved his new family into a bigger home where they would have room for more children. Mom did convert to Judaism and tried to please my father, but it was clear from the beginning that she didn’t want to be a full-time wife and mother. She was just not emotionally prepared for the responsibility. My grandmother and a nanny took over my care, and that really disappointed Dad. He needed a strong partner and instead found himself with a child bride.

My grandparents had opposed the marriage from the very beginning. The age difference was a big concern, not to mention the different religions. But, ironically, they had done exactly the same thing, my grandfather being from a Roman Catholic family and my grandmother from an Orthodox Jewish one. The age difference between my grandparents was also significant—twelve years as compared to fifteen for my parents. One needed to convert, so Grandma converted to Catholicism and had six children, all raised in the Catholic faith. While they were both disowned by their parents the day they got married, my mother was able to keep in touch with her family after she got married, perhaps because my grandparents identified with her situation even though they opposed the marriage. My grandmother was deeply concerned that, being so young, Mom would not understand the horrors that my father suffered during the war and would not know how to be a supportive partner to my father.

I was almost one year old when the vinegar factory was ready for the grand opening. The day after the grand opening, Dad went to the factory to open for business, only to find that government officials had taken over the building. Unfortunately, by this time Hungary was a Communist country under Soviet occupation, and the party was in the process of taking over all the privately owned businesses. They informed my father that the factory was now officially government property, and he was told to leave. When he asked if he could go in to pick up his work jacket and the briefcase he left in his office, he was not even allowed to do that.

The Soviet Union asserted legal authority to seize private assets from occupied territories. Beginning with the Communist revolution, it became policy for the Soviet state to take lands and assets from the nobility and redistribute this wealth among the peasantry. Following the Potsdam Agreement between the primary Allied countries (Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union) in July 1945, which laid out the laws governing Germany’s demilitarization and war reparations, the Soviets were able to take advantage of loopholes to justify nearly any property seizure they wished under a veneer of legality. For instance, if any company was wholly or in part owned by German or Austrian interests, the seizure of that asset was justified as war reparation. This affected Hungary greatly because many Hungarian companies were partnered with Austrian companies. In any event, this essentially gave the Soviets carte blanche—they could take any property or business they wished and dedicate it to their agenda.

This happened everywhere in Hungary and all over Eastern Europe. Of course, the Communist government waited until the factories and other businesses were rebuilt before they took them over. This was a common practice by the communists—letting the private businesses do the rebuilding at their own expense so that when the factories were surrendered the government could start operations immediately and reap all the benefits without those expenses.

My father was again facing an uncertain future, and this time with a young family. Losing the factory—which was the only thing left from his family’s business and in which he had invested all the remaining family’s assets—was devastating. These were hard times for everybody, and I don’t believe that my mother ever fully realized the pressure my father was under. She was a beautiful young woman, but had no idea how to be a supportive wife and partner to my father during those trying years.

After losing the factory, Dad moved his young family to Budapest, the largest city and capital of Hungary, where he thought he might have more opportunities to find employment. But Budapest was struggling to rebuild after the war, and life was very hard there, too. The city had suffered major damage and casualties in the last year of the war, after Germany occupied Hungary. In February 1945, the city was nearly destroyed in the Battle of Budapest. After being subjected to massive air raids by the Allied forces and ground fighting between attacking Soviet forces and defending Hungarian or German forces, nearly forty thousand civilians lost their lives, and every bridge over the Danube had been destroyed.

I was two years old when we moved to Budapest. By this time my parents’ marriage was floundering. Dad wasn’t getting the support he needed from my mother, and she had no concept of the magnitude of his losses—emotionally, physically, and financially. He had lost his entire family, he had lost the factory (and the family money he used to rebuild it), and he had lost his right arm and with it his dreams of becoming a concert cellist. Now even his marriage was falling apart and he did not know where to turn next.

Dad was beginning to lose hope of being able to start over again. As luck would have it—I would rather say it was God’s intervention—he ran into an old friend in Budapest one afternoon when he was just taking a walk and wondering how to go on, almost ready to give up the fight to survive. His friend, Katinka Daniel, a respected piano teacher, knew my father from the time when they were both studying at the Budapest Music Academy. Her husband, Dr. Erno Daniel, was a young conductor.

When Katinka saw Dad she was overjoyed that he was alive and had survived persecution during the war. Katinka had a lot to tell my father, also. Her beloved husband, Erno, left Hungary to go west just before the war ended, with the promise to build a better life for her and their two children in America. Katinka was left by herself to raise her children alone, but her faith was strong and she knew her husband would keep his word and that they would eventually reunite. They did, but it took twelve years.

The friendship between Katinka and my father came at the right time, and they helped each other a lot. Dad was obviously struggling, but Katinka, a deeply religious Christian woman, was very encouraging. She helped my father get a job teaching cello to young students, and he also started conducting the Hungarian Communist Party Chorus, with Katinka accompanying him on piano. During this time Dad also went back to school and got his master’s degree in music. Eventually he became one of the most well-known and highly regarded cello teachers in the country, and his close friendship with the Daniel family lasted throughout their lives.

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 2

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 2

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 2

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 2

Picture of the young bride.

The newlyweds: mom and dad.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

First year of marriage; still a happy couple before my early arrival.

One of my favorite pictures of my handsome dad.

Last family photo taken on April 25, 1949; the day after my second birthday. The marriage was already in trouble.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Last picture of my grandmother, the year before she passed away.

Grandmother, dressed for church.

The only picture of my maternal grandmother and grandfather together; they were married almost 60 years.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Chapter 3

My Childhood

My full birth name was Ildiko Judit Kalman. My mother named me Ildiko after the last wife of Attila the Hun. Some legends say that the teenage bride Ildiko killed Attila on the night of their marriage for forcing her into it, or for the murder of her family, while others say he died on their wedding night from a sudden hemorrhage. While lost in the fog of legend, the name itself is certainly Germanic in origin, sharing the same root with Hildegard and Hildchen, and has come to mean “fighter” or “fierce warrior.” Considering the trials of my life in Hungary, I feel this is quite appropriate, and I am proud that my name is a symbol of the strength I needed to survive those difficult years. My middle name, Judit, was in honor of my father’s niece (the daughter of his sister, Irene) who perished at Auschwitz.

According to my grandmother, I surprised everyone by arriving two months earlier than expected. She would often joke that I was in such a hurry to enter this world, and that nothing much has changed since that time. I still tend to be in a hurry in everything I do. I like to be early whenever possible, especially when I promise to be somewhere for our children; and I am fanatical about arriving early at airports!

Since I was premature, things didn’t look too good for me at first. Mom told me that I was not a pretty baby, and that at first she didn’t want my father to see me because she was afraid he would not believe that I was his child. I think she really had no idea how to take care of me. Mom had no interest in nursing me at all, so we had a nanny with enough milk for babies. She fed me while she was nursing her own baby, too. I was a sickly infant, very colicky, and didn’t grow at the normal rate. My grandmother, having raised six children, quickly realized that I wasn’t getting enough nutrition, and this was why I wasn’t growing and kept losing weight. According to my folks, I cried constantly and slept very little. For a while it was questionable whether I was going to

survive. The family doctor kept giving me shots to keep me alive, but that is not what I needed.

One day my feisty grandmother happened to visit when our doctor was at our house administering one of my many shots. Of course, I was crying, and according to Grandmother it was mostly from hunger. She loved to tell me the story of the time she literally threw the doctor out of the house because he was giving me shots and collecting money from my parents when all I needed was some food. Grandma then brought in a live chicken and some fresh vegetables from her garden. She prepared a big container of chicken soup, poured it through a strainer, and put the nutritious liquid in a bottle. She fed me and for the first time I slept more than twenty-four hours. When I finally woke up, I didn’t cry. From that moment on Grandma took over my care and I began to grow at a fast pace.

Six months later my grandmother ran into our former family doctor when she was taking me for a walk in the stroller, and he did not recognize me at all, confusing me with my cousin Agi, who was only ten days older than me. Within a couple of months under my loving grandmother’s care I had filled out, my eyes changed from brown to blue, and my dark hair slowly fell out and was replaced with blond curls (I did begin to resemble Agi, as we were both blond children). Until the end of her life my grandmother swore that her chicken soup saved my life. To this day, chicken soup is still one of my favorite foods.

We moved into one of the nicer neighborhoods in Budapest in 1949. Our address was 84 Vaci Street. Our flat was on the fourth floor, and was nicely furnished as I recall. From our window I could see Gellert Mountain with the Freedom Statue, where they had fireworks for Worker’s Day every May 1. My kindergarten was just a few blocks away, as were the Danube River and the Freedom Bridge. Once we moved to Budapest, we no longer had domestic help the way we had in Miskolc, and my mother did not adjust well to her new circumstances. She was not willing to take on the responsibility of being a supportive wife to my father and mother to me. She was then twenty years old.

Dad began to teach cello, and he became the head conductor for the Hungarian Communist Party Chorus. We had a lot of company in the evenings, mostly musicians who were either playing in the Budapest Symphony or teaching music like my father. Dad worked very long hours, and money was tight. Everyone was just trying to survive under the new Communist regime. I clearly remember the constant quarrels between Mom and Dad each night after the guests left. I could tell something was very wrong, but I didn’t really understand any of it. Somehow, though, I suspected that my parents might have cheated on each other, and I was filled with fear that they might abandon me. I could tell that my father was angry with my mother for not taking care of me, while she would make excuses and blame Dad for my existence. Clearly, motherhood was not her calling.

In the winter of 1951, I got very sick with the mumps and was running a very high fever. I still remember the nice, elderly family doctor who came and gave me medication. I was happy when he came over because my parents wouldn’t quarrel in front of him. One particular night I woke up from a feverish sleep and heard the yelling between Mom and Dad. It was frightening. The next thing I remember, Dad stormed out of the apartment and left. Mom was crying, and then minutes later she grabbed her purse and took off as well.

Thank goodness they left all the lights on. I got out of bed to run after them, but the door was locked. This was exactly what I feared the most—that I would be left alone without my parents. In my confused state I imagined all sorts of frightening things. I was sure that I was going to die and nobody would care. I started crying, and I must have cried for so long and so loud that our next-door neighbor heard me and became concerned. He called the building manager who came up with his wife. They broke the lock on the door to our flat and stayed with me until the morning. I remember that when my parents finally did return it was getting light outside. This feeling of being left alone so often at such a young age (I was then four) really affected me as I began raising my own children. It became almost an obsession never to leave them alone, especially our daughter. Even when they were away at college I was always asking them if they were alone. I just could not relax until I was certain that they had a friend, a roommate, or someone with them.

When I asked my parents why they left me, Dad told me he thought Mom would stay with me. Mom said she thought she would only be gone a short time. The truth is, they were busy dealing with their own issues and forgot about me. When their fighting continued it became obvious to me that both of them spent that night with other people And my existence made their lives a lot more complicated. To this day I don’t know how I knew this, but somehow I did. Sadly, I learned later that my suspicions were correct. During their constant quarrels I recognized some of the names of the people with whom they suspected each other of being unfaithful. It broke my heart, and I just wanted to disappear. Did my mother and father ever love each other?

The following week Dad moved out of our home and into a one-bedroom studio apartment not far from our Vaci Street flat. He left everything behind for my mother. He took only his clothes and the grand piano and music books that he needed for his teaching jobs. The divorce proceedings were concluded fairly quickly. Mom cried a lot and kept asking me to ask Dad to come back home. A few times I made an attempt to convince him to try again, but he was very bitter and wouldn’t even talk to me about Mom. He tried very hard never to look back but at the same time did his very best to take care of me under these difficult circumstances. He worked long hours, six to seven days a week, and I was grateful to be with him during the early morning and late in the evening. During the week Dad took me to kindergarten in the morning, picked me up at six o’clock and I stayed with him at his school until he finished teaching usually around ten o’clock at night. He was teaching or performing with his chorus most weekends but he always took me with him. It meant a lot to me that he never left me alone, he was always on time to pick me up from kindergarten and he made me feel that I was important to him.

During my preschool and kindergarten years, I was always the last kid to be picked up after school when it was my mother’s turn (if she even came at all). Most of the time, the person who would come for me was my father. Mom rarely made it, and when she did, it was always very late and I would often be out on the street waiting for her after the school closed at six in the evening. Sometimes I just walked home because I was too embarrassed to be the last one left at school all the time. I would make up stories about how my mother had to work and that was why she could not come and get me. In truth, I never knew where she was. Sometimes the neighbors would feel sorry for me and invite me into their flats to wait for Mom to show up. I was very grateful for their kindness, especially in the freezing winter when being on the street was no fun at all.

When I was walking around on the streets looking for my mother, it never occurred to me that I might be molested or that somebody could really hurt me. Sometimes, when I had no place to go, I would take the streetcar to be with my grandmother, who always welcomed me with so much love and concern. I knew I would be safe with her and my grandfather. We would always pray together for my mother and father. Of course, I always prayed for the impossible: that my parents would one day reconcile so that we could become a normal family.

I spent a lot of time sitting on the staircase by our front door until Mom came home. Sadly, she usually had a male companion with her, so even when she did come home I felt like I was in the way most of the time. Men were attracted to my mother like bees to honey. She was very beautiful and had the most amazing laugh. Whenever I was with her I always noticed how men just looked at her in a way that made me feel very uncomfortable. I sensed that my presence was not always welcome. Mom loved all the attention from the opposite sex and seeking that attention consumed her life.

Looking back now, I realize that my mother had no idea what I was feeling. She was totally absorbed in her own life and her own needs, and had no knowledge of all the tears I shed through so many nights while she was sleeping with different men. I tried hard to be a good kid, and I could never understand why I wasn’t wanted by my own mother. I was grateful that I at least I had my father, who never broke a promise to me. Although he was not overly affectionate, whenever it was his turn to take care of me, he never let me down. I was vaguely aware that my father also had some lady friends, but it never interfered with his parental responsibilities.

Dad’s hours teaching cello were long. Often, his days began at 8:00 a.m. and didn’t end until 10:00 p.m. He often picked me up from kindergarten at six in the evening and took me back to the school where he was giving cello lessons to his gifted students late into the night. We would have supper in his tiny studio apartment. Our meals were very simple. We usually drank tea with some day-old bread with dried salami and maybe an apple, if they were in season. I was just happy because I had my dad all to myself. I was also eager to help my father in any way I could so I could stay with him longer. I began helping him wash his socks and undergarments in a small sink by his room after I saw him struggling to do this simple task with one hand. I always helped him fix our supper and cleaned up afterward so I could prove to him that I was useful and could take care of things around his place.

I used to wonder why the divorce judge didn’t award custody of me to my dad, since he did his best to look after me. It never occurred to me that the judge looked at him and saw a man with one arm who worked long hours trying to make ends meet. Dad was living in a small one-room apartment, sharing a common bathroom with three other tenants. Though this was not ideal for a little girl at age five, obviously the judge didn’t know that my father could do more with his one arm than most people could with two.

Mom got a job at a café in Budapest and started to make some money. I knew she got good tips from male customers because she was attractive and fun to be around. She also received child support from my father, which she apparently spent mostly on new clothes and going out with friends. I don’t believe she did that to hurt me in any way; she was just young and irresponsible. I also think she simply wanted to be independent and enjoy her life. She never finished high school but was curious, smart, and eager to learn about the world around her. She was young and beautiful and loved all the attention she got because men were attracted to her. Although her formal education was not completed, she loved to read and was knowledgeable about the arts.

She met her second husband while working at the café in Budapest. He was everything my mother wanted at the time. He was good-looking and well-educated, very sophisticated in my mother’s eyes. She became totally obsessed with this man. His name was George, and he took Mom to the theater, opera, poetry readings, and the horse races (later I learned he was addicted to both gambling and sex). Unfortunately, this relationship hastened a long downward spiral for my mom.

I remember always asking my father to let me live with him because it was unbearable when George was around my mother. I was losing my mother completely to this man. I also started noticing that we had less and less furniture in our flat. I learned later that Mom had started to sell some of the furniture, giving the money to George to feed his gambling habit.

In our one-bedroom flat there was very little room for me, and it was apparent that George didn’t particularly like having me around. Often I would take the long bus ride to the suburbs of Budapest where my grandmother and grandfather lived, just to get away from him. I was too embarrassed to tell my father all the things that went on between my mother and George at home, but I was always asking Dad to take me to his place. I never complained about his long working hours as long as I could be there with him.

One day my father sat me down and told me that things needed to change so I would have more stability in my life. He told me it was very important that I get a good education so I could be successful when I grew up. He said that he had arranged for me to move into the Jewish Orphanage in Budapest in the fall of 1953. I would be six years old. Since technically I was not an orphan, I was getting some special considerations and Dad would pay a nominal fee for my keep. He was allowed to come to see me twice a week to give me cello lessons, which I was about to start during my first year in school. He also promised me that every summer when school was out we would spend our vacations together.

This was a very confusing time for me. I thought, If I have a mother and father, why do I have to be in an orphanage? What have I done that my parents don’t want me to be around? Why don’t they love me? I also wondered why, if I was baptized Roman Catholic, I was going to a Jewish orphanage. I was certain that there had to be something wrong with me. Was I being punished for something? I spent so many sleepless nights praying and wondering what I could do so my mom and dad would get back together again and want to be with me.

When my mother found out that Dad was enrolling me in the Jewish Orphanage, she became very upset. For a very brief moment I thought she might fight for me and would decide to look after me after all. Sadly, I think that she was upset because she was about to lose the child support that Dad paid her for my care. After I moved into the orphanage these payments would no longer be required, and she would lose part of her monthly income.

I recall my last Christmas at home on Vaci Street before moving into the orphanage. Mom and I were decorating the tree with George. My father was coming over to visit and celebrate Christmas with us in the afternoon, and I was both excited and nervous because he was going to meet George, whom I hated with a passion. This man was destroying my secret dream that somehow my parents would get back together and we would be a normal family once again. I was also sad for my father because I didn’t know how he would feel seeing my mother so close to another man in the same home which they had shared together.

When my father arrived I was overjoyed. I just ran into his arms and hung on for dear life. He had a little box for me, and in it was a beautiful little Danish doll. The minute I took the doll out of the box I loved it more than anything in the world. That Danish doll was going to be my most special possession.

There was also a beautiful doll from France under the tree in a big box. Mom said the doll was a special gift from George to me. Now, it was very important to me that my father knew how much I loathed George and wanted to get away from him. I also wanted my mother to know that I hated the French doll and didn’t want to stay with her and George. So I took their fancy doll and tore the clothes from her body, pulled her head off, and literally destroyed her within seconds.

After my father left I got spanked for ruining the French doll, but frankly, I didn’t care. I just had to do something to show my anger and pain. I also intuited that the French doll was not a gift from George, that really Mom had bought it and told me it was from him in an effort to get me to like him. Unfortunately, George stayed in my mother’s life for many years. Mom told me, when I was an adult, that the physical attraction between them was so powerful that she simply didn’t have the willpower to leave him. Even after she lost her home and everything that my father left for her, she kept George in her life for a long time.

The little Danish doll my father gave me was my treasured toy for many years. She was my friend, and I took her with me everywhere. When I moved into the orphanage I took her to my grandmother’s place for safekeeping, so nothing would happen to her. Every time I stayed with Grandma I would play with my little Danish doll for hours on end. She was dressed in the traditional Danish clothing with lots of underskirts, a printed blouse, a vest, a colorful apron, and a traditional Danish hat. She had lace socks and clogs. Her beautiful blond hair was braided and long. I would redo her hair and redesign her clothes over and over.

I made many outfits out of her underskirts and apron and was always trying to come up with different looks. Grandmother used to watch me and say, “I wonder what you are going to be when you grow up?” Little did I know (and I never would have dreamed it then) that most of my professional life would be spent in the fashion industry, dressing people, doing runway shows, and making regular fashion presentations on a popular morning television program in San Francisco!

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 3

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 3

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 3

Love’s Orphan

Chapter 3

My classmates from middle school. My best friend Bea is in the second row, fourth from the right; I am in the last row second from the left.

My first solo performance during one of the fundraiser events for the Orphanage.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Picture from second grade in 1954.

Love’s Orphan

Chapter

Chapter 4

The Orphanage

In September 1953 my father moved me into the orphanage, and it was to be my home for most of the next ten years. It was on Delibab Street, just on the outskirts of the famous City Park. It was a big yellow building with a tall wrought-iron fence surrounding it. The view from the courtyard was very nice, overlooking the statues of Hungarian kings, which stood in a half-circle on what is appropriately called Heroes Square. On one side of the square was the world-famous Hungarian National Art Museum, and on the other was the Museum of Modern Art. I spent many hours in those museums on school field trips.

To my surprise, Mom did come to see me the day I moved into my new home. For a moment I thought maybe my parents were feeling sorry for me and had decided I didn’t really belong in an orphanage after all. Instead, they began to argue again about everything, and it escalated as usual. They said a lot of hurtful things to each other, and it was embarrassing and uncomfortable. Mom kept screaming at my father that there was no reason for me to be in the orphanage, and Dad kept saying that she was not fit to be my mother. I felt that my heart was going to break. They were arguing in front of me as if I didn’t exist. I still remember having the same thoughts I had before: Have they ever really loved each other? Do they really love me? It seemed to me that I was always the problem.

I was sobbing uncontrollably and begged Dad not to leave me, but he kept assuring me that this was the right place for me to be for now, that this was a better situation for me than being on the street waiting for Mom to come home, or sitting in a classroom late into the night waiting for him to finish teaching. He explained to me that I needed stability and structure in my life and that, more than anything, I needed to be in a place where I was safe. I was only six years old, and I was trying really hard to understand and accept my new life. In my heart all I felt was complete rejection. And then it was time to say good-bye. My mother promised she would get me out of this place soon, but she never did. In fact, she hardly ever came to see me.

The Jewish Orphanage was supported by Holocaust survivors in Budapest as well as people who had emigrated from Hungary to Israel or the United States before the German occupation. This was an Orthodox Jewish institution. The headmistress was named Aunt Olga. Her office was on the first floor. She seemed stern and cold to me (and I thought at the time that she was probably the most unattractive-looking woman I have ever seen). Throughout my time at the orphanage I was scared to death of her.

Aunt Olga knew my father and spoke of him with great respect. Everyone seemed to know Dad, who by this time was making a name for himself as a noteworthy cello teacher. He made arrangements with Aunt Olga to see me on Wednesdays and Sundays to give me cello lessons, and this was when he surprised me with my first cello. I started dreaming about becoming a great cellist. I thought if I worked hard the way he did I could fulfill the dream of my father. I could bring back to him something so valuable that he had lost, and also make him proud of me.

For a long time I was terribly lonely in the orphanage; I just could not make friends with anyone. I remember looking around the courtyard and seeing many girls of all ages running around playing games, but no one seemed to pay any attention to me. Looking back, I think I know why that happened. I wasn’t an orphan like nearly all the other children. Also, though my hair had grown darker by then, I noticed that I was the only blond-haired, blue-eyed kid out of eighty-five girls. Everyone else had dark brown or black curly hair, so I just stuck out. They used to tease me nonstop about my looks. The first couple of years I cried myself to sleep almost every night.

Then, when I was in third grade, Bea Frank came to the orphanage. She soon became my very best friend. Our friendship helped both of us to get through those tough times. We had a lot in common: like me, she wasn’t an orphan, either. Her mom was not in good health, and her dad just disappeared one day, leaving home to pick up a pack of cigarettes and never coming back. During the early fifties it was not unusual for people simply to vanish for no apparent reason. The KGB controlled everything, and you never knew who was listening in to your conversations.

Bea and I were complete opposites in looks. She was skinny and sick all the time with asthma. She had very thick brown hair, light olive skin, and big brown almond-shaped eyes. I was lily-white with rosy cheeks, plump and healthy-looking. But Bea and I loved all the same things. We would make up stories about what we would do when we left the orphanage. We had big dreams for our futures.

We were lucky because Bea sat next to me in the study room in the orphanage and her bed was also assigned next to mine. We studied together and loved reading, theater, and movies. We started a scrapbook about all of our favorite actors and actresses. We were definitely star-struck! We were completely infatuated with the same actors and imagined what we would say if we ever met them. We created our own fantasy world and had a lot of innocent fun.

We also started writing a daily diary. I think we got our inspiration from the book The Diary of Anne Frank. We both instinctively knew that we lived in unusual times that should be recorded. We would often compare our entries and share our most secret thoughts and dreams. And we shed many tears talking about our lives, yet we could also make each other laugh and forget about our often difficult daily reality.

We used to save every penny to buy tickets to the movies or theater. We talked a lot about going to America, where it seemed everybody wanted to go. In school, however, we were taught that America was evil and that it was about rich people taking advantage of poor people. We were brainwashed with daily dogma from The Communist Manifesto that the only way to succeed was to support the Communist Party, where everybody was equal and had the same rights.

We were always told that we had to give everything to the Soviet Union because they “liberated” us from the Nazis and we owed them our freedom. We studied the lives of Stalin, Lenin, and Marx in school, and their statues were displayed everywhere. We had red stars on every building and all the children were required to become Pioneers, members of a youth Communist organization. All of us had to wear a red kerchief around our necks showing our solidarity with the Soviet Union. Our streets were renamed after “Soviet heroes.”

Under Communist rule there was no freedom of religion, though at the Jewish orphanage we had religious instruction weekly. In public school classes, however, the story was completely different. Both Bea and I believed deeply in God, but in school God was never mentioned, as if He didn’t exist. In books and poems the word God was never capitalized, and when we asked the teacher why God’s name wasn’t written with a capital G she answered, without blinking an eye, “Because there is no God.” Then we saw that very same teacher in the Jewish temple the following Friday at the evening services. We were so indoctrinated with the Communist ideology that we just accepted these double standards as a way of life.

There was one thing we never understood, though. If America was so bad, then why did people want to go there? If the Soviet occupation was so great, then why were people always talking about leaving Hungary to go west for a better life? Bea and I would try to see every American movie, and we would dream about this other world. Even though we knew nothing about it, we both knew we wanted to go there!

The schedule at the orphanage was like being in the military. We wore uniforms to the public school, but underneath we had to wear dresses made by the in-house seamstress at the orphanage. Everybody had a number that was sewn into our towels and our clothes. I was number 11. At school we were always so embarrassed about our clothing because everyone knew that we were the girls from the Jewish orphanage. I remember how humiliated I felt because nobody in school wanted to be friends with us. Even though the war was over, Jews were merely tolerated but not particularly liked. Anti-Semitism was rampant in Hungary and all over Eastern Europe, but nobody talked openly about it.

We had to wake up every morning at six o’clock sharp. Usually, a supervisor would be at the door of the large bedroom where most of us slept. They would have a bucket of cold water ready in case someone decided not to jump out of bed immediately. I tried always to be up early to avoid the cold water treatment!

We had to line up at the communal bathroom sinks to wash our faces, brush our teeth, and then be dressed by 6:30 a.m. Beds had to be made neatly, and then we lined up for breakfast. We had a long main dining room in the basement where we ate at assigned seats, usually decided by what grade we were in school. Breakfast was always the same: coffee with milk and a thick slice of bread (sometimes buttered). It ended at 7:00 a.m., and then we had to go back upstairs to get our school bags, snacks, and coats. After that we lined up downstairs for roll call at 7:15 a.m. We then walked to the nearby public school, which started promptly at 8:00 a.m.

There was an incident that happened one morning at roll call that I could not forget, mainly because it involved my best friend, Bea. We were not allowed to have bangs, and our hair had to be completely out of our faces. Bea did have bangs, but she carefully combed it under her cap, secured with some hairpins. Her hair, however, was very thick in texture and hard to control. She was trying to hide her bangs to get through roll call. Unfortunately, this particular morning her hair would not cooperate and her bangs slipped out just as we were being checked. Aunt Olga was livid and proceeded to get scissors and cut Bea’s bangs completely off. It was a miserable scene. Bea cried, and I cried with her. Oh, how I hated that woman in that moment! To this day I still don’t understand what she had against bangs; I thought they looked really pretty on Bea.

We got out of school at 2:00 p.m., and then we walked back to the orphanage and had our main meal in the dining room. It was a regular meal with soup, vegetables or potatoes, and sometimes meat or a stew. Then it was time to do homework until 7:00 p.m. All our assigned work was always checked by our supervisor before we finished for the day. At 7:30 we had supper, which usually consisted of hot tea and some buttered bread. Then we had playtime, but I usually took this opportunity to practice my cello. At 9:00 it was bedtime.

There was a temple in the orphanage building that we attended every Friday night and Saturday morning. We also had religious instruction every Wednesday evening, taught by the wife of the rabbi who conducted the services on Fridays and Saturdays. Her name was Aunt Margaret, and she was a wonderful storyteller. I always looked forward to Wednesdays, when I would see my father in the afternoon for cello lessons and would then be with Aunt Margaret in the evening.

I loved being in our temple. It was the place where I practiced my cello and got to spend time alone with my father. I still remember the special smell in the temple, a combination of the fragrance of candles, the dark oak pews, and the old Hebrew prayer books. I always felt safe there.

It was a very spiritual experience practicing my cello on the podium where the rabbi gave his sermon every week. There were two large oil paintings in the temple covering the walls facing the pews. One of them was the painting of Moses parting the Red Sea as the Jews were escaping from forty years of captivity in Egypt. The other painting was of Moses with the burning bush. I always practiced my cello as close to these paintings as I could because they made me feel protected and safe. I felt as if a guardian angel were watching over me when I looked at them. I used to pretend there was a big audience in the temple, and it definitely helped me to be less nervous when I later actually started performing in front of larger audiences.

The food in the orphanage was prepared in the Jewish Orthodox tradition, but I never liked it much. We had to say our prayers in Hebrew before every meal. Our supervisors would walk around and watch us eat until we finished our meal. We were not allowed to leave until our plates were completely empty. Most Fridays we had liver and some kind of grits that I simply could not swallow. When the supervisors weren’t looking, Bea and I would wrap the liver in our napkins, hide it in our apron pockets, and then flush it down the toilet as soon as we left the dining room. I remember thinking that if I ever got out of there my lips would never touch liver ever again. I have kept that promise!