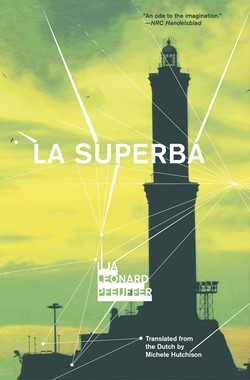

Читать книгу La Superba - Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer - Страница 8

ОглавлениеThe Most Beautiful Girl in Genoa

1.

The most beautiful girl in Genoa works in the Bar of Mirrors. She is neatly dressed like all the girls who work there. She also has a boyfriend who drops in on her from time to time at work. He uses hair gel and wears a sleeveless t-shirt with SOHO on it. He’s an asshole. Sometimes I watch them in the mirrors, kissing secretly in the cubbyhole where she prepares the small dishes they serve free with the aperitif.

This morning on the Via della Maddelena I saw someone who’d been mugged. “Al ladro!” he shouted. “Al ladro!” Then a boy came running round the corner. The man chased after him. He was wearing a white vest and he had a fat face and a fat belly. He looked like an honest man who’d learned to work hard for paltry pay from a young age. The boy ran uphill, to the Via Garibaldi, past the sundial and then carried on climbing, up the steps of the Salita San Francesco. The fat man who had been mugged didn’t stand a chance.

Later I sat drinking on the Piazza delle Erbe. It’s an unusual kind of place, evening just happens there without me having to organize anything. The little orange tables belong to the Bar Berto, the oldest pub on the square, famous for its aperitif. The white tables belong to the nameless trattoria where it’s impossible to eat without a booking. The red and yellow tables belong to various cafés and behind them there’s another terrace, a little lower down. I can look up the names if you’re interested. I was sitting at a blue table on the upper part of the square, looking out onto Bar Berto’s terrace. The blue tables belong to Threegaio, set up by three homosexuals who brainstormed for days on end and still couldn’t come up with a better name than that. I was drinking Vermentino from the Golfo di Tigullio. An impressive looking she-man wearing very dark sunglasses was sitting on a bar stool in front of the building. It was a reassuring sight, she was always there. Street musicians. Rose sellers. And then she spoke to me, “There’s something feminine about you.” She ran her fingers through my hair like a man claiming something as his own. “What’s your name?” Her voice was like a dockworker’s. “Don’t worry, I know. I’ll call you Giulia.”

That night there was a short but violent thunderstorm. I was on my way home when it started. I sheltered in an arcade. It had an official name I noticed later: Archivolto Mongiardino. The black sky lit up green. I’d never seen anything like it. The rain clattered down like two cast iron portcullises on either side of the vault. After a few minutes it stopped.

But the streetlights had gone out. In the alleys barely penetrated by daylight, a medieval darkness reigned. My house wasn’t far. I could find it by feeling my way, I was sure. Yes, the street went upwards here. This had to be Vico Vegetti. To my left and right, I felt scaffolding. That was right. There were renovations here. And then I almost tripped over something. A wooden beam or something similar. That’s what it felt like. Dangerous leaving something like that lying around in the street. I bent down to move it to one side. But it didn’t feel like wood. It was too cold and slippery for that. It was too rounded to be a beam. It felt strange, and a bit disgusting, too. I tried to use the light of my mobile phone as a torch, but it was too weak. I was almost home. I decided to push the thing behind the builders’ dumpsters and come back the next day to examine it. I was curious. I really wanted to know what it was.

2.

Prostitutes are for lunch. They appear around eleven or half past eleven. They hang around in the labyrinth of alleyways in the sloping triangle between Via Garibaldi, Via San Luca, and Via Luccoli, on either side of the Via della Maddalena, in small dark streets with poetic names like Vico della Rosa, Vico dei Angeli, and Vico ai Quattro Canti di San Francisco. In these alleys the sun doesn’t even shine at midday. They lean there casually against doorposts or sit in clusters on the street. They say things like “amore” to me. They say that they love me and they want me to come with them. They say they want to run their fingers through my hair. They are black. They are blacker than the anthracite shadows in this city’s entrails. They give off the smell of night in the afternoon. They stand there on haughty, towering legs, a flickering glimmer of arrogance in their eyes. They sink their white teeth into men’s pale white flesh. I don’t know how I’d ever get out alive. Civil servants with leather briefcases dart away skittishly.

Later I see them again in the Galleria Mazzini: Genoa’s magistrates in their shirtsleeves, dark blue jackets slung across their shoulders, their calf-leather briefcases filled with the few documents of any real importance in their sole charge. They like to walk on the marble floor, past the antiques on display, enjoying the lofty reverberations of their footsteps under the crystalline roof. Griffins with the Genoese coat of arms on their chests support the chandeliers, their beaks twisted with arrogance. If you walk through the Galleria from the Piazza Corvetto, you come out at the Opera. Where else?

I walked toward the sea. In the distance, a yellow airplane glided over the waves and scooped up water. There were forest fires in the mountains. I know people who can tell tomorrow’s weather from the height at which the swallows soar. But the low flight of a fire plane is the most reliable indication of a blistering summer.

I’ve bought myself a new wardrobe so that I can slip into this elegant new world a new man. A couple of Italian summer suits, tailored shirts, an elegant pair of shoes, as soft as butter but as sharp as a knife, and a real panama hat. It cost me a fortune, but I considered it a necessary investment to give my assimilation a boost.

That evening, I spoke to Rashid. He sells roses. I usually bump into him a couple of times a night. I offered him a drink. He came to sit with me for a while. He was from Casablanca, he said, an engineer who specialized in air-conditioning and refrigeration. In Casablanca, he has a large house but no money. That’s why he came to Genoa, but he can’t get a job because he doesn’t speak Italian. During the day, he tries to learn Italian from YouTube videos. In the evenings, he sells roses. Every evening he does the rounds of all the terraces to Nervi. Then he walks back. To Nervi and back is twenty-four kilometers. He lives with eleven other Moroccans in a two-room apartment. “Of course there are rats, but luckily they aren’t that big. All Moroccans think you can get rich without even trying in Europe. Of course they won’t go back until they’ve saved enough to rent a Mercedes for a fortnight and put on a show that they’ve become spectacularly rich and successful in Europe. It’s a fairy tale that gets better with every retelling. But I’ve seen the reality, Ilja. I’ve seen the reality.”

When I walked home, the flag was fluttering high on top of the Palazzo Ducale’s towers. It wasn’t the European flag, nor the Italian flag. It was a red cross on a white background: the Genoese flag. La Superba. Above the harbor and in the distance, above the black mountains of Liguria, I heard the griffins screeching.

And then it came back to me. The previous night I’d stumbled over an object in the dark on the Vico Vegetti. And I’d hidden the object behind a garbage can. Now the streetlights were working again and I was actually quite curious.

But the thing wasn’t there anymore. There was all kinds of stuff near the garbage cans down on the corner of the Piazza San Bernardo, but nothing you could stumble over. Well, perhaps it wasn’t that important. Besides, I realized that showing so much interest in garbage might look a bit funny to the few passersby. In any case, it wasn’t the image I wanted to adopt as a proud, brand-new immigrant to the city. I went home.

But a little higher up in the alleyway, near the scaffolding, there was a dumpster full of builders’ waste. I remembered clinging onto the scaffolding in the pitch dark when the power cut out. On the off chance, I looked to see whether the thing might be there. At first I didn’t see it, but then I did. I looked back over my shoulder to see if anyone was looking, picked it up, and got the fright of my life.

It was a leg—a woman’s leg. Unmistakably a woman’s leg. And when it had been in the right context, it had been attractive—slender and long, perfectly proportioned. It was no longer wearing a shoe, but it still had on a stocking, the long, old-fashioned kind that only models on the Internet still wore. To cut to the chase, there I was, in the middle of the night, in my new foreign city holding an amputated female leg, and, all things considered, this didn’t seem to me the ideal start to my new life. Maybe I should call the police. But maybe I’d better not. I put the leg back and went off to bed.

But later I awoke with a start, bathed in sweat. How could I have been so stupid? Of course I could tell myself that I had my own reasons—which for that matter many would have found understandable—for not wanting to have anything to do with a chopped-off woman’s leg I’d accidentally discovered in a public place—but I’d stood there holding it in my hands. What I’m saying is I’d stood there groping it twice with my callow, canicular paws. Hadn’t I ever heard of fingerprints? Or DNA evidence? And when the leg attracted the attention of the carabinieri, which sooner or later it was likely to do, would they carelessly toss it to one side as yet another sawn-off woman’s leg found in the alleyways, or wouldn’t they possibly be curious as to whom it had belonged to, who had amputated it, and whether this had happened with the approval of its rightful owner? And wouldn’t they, once that curiosity had taken root, carry out a simple search for clues? And wasn’t an investigation of the neighborhood then quite an obvious next step? Wake up, you dope.

But I no longer needed to tell myself that. I was already wide awake. More than that, I was already getting dressed. It was still nighttime, dark, no one about. I had to act quickly. The leg was still there. I didn’t have any kind of detailed plan, but removing the corpus delicti from the public arena seemed a sensible place to start. I took it home with me and leaned it against the back of the IKEA wardrobe in my bedroom.

3.

I want to be part of this world. When I woke up, I heard the city starting to chew the day between her ancient, rotten teeth. In different parts of the neighborhood, her crumbling ivories were being drilled. Neighbors swore at each other through open windows. On the wall of the palazzo my bedroom looked out on, someone had written that all smiles are mysterious. Someone else had written that he thinks the Genoa football club is better than the Sampdoria football club, but in terms much more explicit than that. Someone else had written that he loved a girl named Diana and that to him she was a dream become reality. Later on, he or somebody else had crossed out the confession. There was garbage on the street. Pigeons pecked around in their own shit.

Today ships will arrive with Dutch, German, and Danish tourists on their way back from Sardinia and Corsica. They arrive dozens of times a day, and the tourists cautiously and reluctantly lose themselves a bit inside the labyrinth for an afternoon. They seldom dare venture much further than the alleys a few meters from the Via San Lorenzo. Others walk along the Via Garibaldi to the Palazzo Rosso and the Palazzo Bianco, oblivious to the dark jungle lying at their feet.

I like tourists. I can watch them and follow them for hours. They are touching in their tired attempts to make something of the day. When I was a boy, school used to give us lists of all the things we shouldn’t forget to take on our school trip. The last item on the list was always “a good mood.” That’s what tourists carry in their rucksacks when they trudge through the streets and look at the map on every corner to try to find out where on earth they are. And why was that again? Finding every building pretty, every square nice, and every little shop cute is a matter of survival. Sweat pours from their foreheads. They think they understand everything, but they’re suspicious at the wrong moments, while not fearing the real dangers. In Genoa, they are more helpless than anywhere else. Incomprehension and insecurity are written all over their faces as they hesitantly wander around the labyrinth. I like them. They’re my brothers. I feel connected to them.

But I want to be part of this world. I want to live in the labyrinth like a happy monster, along with thousands of other happy monsters. I want to nestle in the city’s innards. I want to understand the grinding of its old buildings’ teeth. I went outside and walked along the Vico Vegetti, the Via San Bernado, past the garbage cans and the Piazza Venerosa, down to the Via Canneto Il Lungo to do some shopping at Di per Di. I bought detergent, grissini, and a bottle of wine. Then I took the same route home. But I did happen to be walking along with a plastic bag from Di per Di. My bag was my green card, my residence permit, my asylum. Everyone could see that I’d been admitted. Everyone could see I lived here. I had spoken scarcely more Italian than the words “prego” and “grazie,” but when they spotted my plastic bag from the supermarket, no one could consider me an outsider any longer. I stopped at a kiosk and bought Il Secolo XIX, Genoa’s local paper. I had resolved to read it every day. I clamped it proudly under my arm, making sure it was folded in such a way that everyone could see that it was Il Secolo.

When I got home, I looked at the wall of my building. I live on the ground floor of a tall palazzo in a narrow alleyway that climbs steeply. “Ground floor” is a relative concept for an alley at such a steep gradient. To the right of my entrance, there must be a large area under my bedroom that is probably storage space for the restaurant at number one rosso, which has been closed since my first day here. The whole building is made of deeply-pitted, grayish chunks of rock, crumbling cement, and patches of old layers of plaster here and there. All in all, the entire thing is rotten, peeling, and decayed. But it has been for centuries. And proud of it. When this was built, there was no gas, electricity, running water, television, or Internet. All these amenities had been tacked onto the outside in a makeshift way over the years. There are wires running from the roof along the front wall, entering through holes drilled into the various apartments. The plumbing and sewage have been added to the outside too—a disordered tangle of lead piping. Next to my front door, I noticed a thick pipe entering my house through a hole. And then I saw the sticker again:

derattizzazione in corso

non toccare le esche

The same sticker I had spotted all over the city over the past days had been placed on the water pipes going through the wall into my house, too. I smiled contentedly. I didn’t live in a hotel. I lived in a real building, a real Genoese building with the same sticker as so many other buildings in the city. I must look up what it means at some point, just for the fun of it.

4.

My waitress has had a nasty fall. Or something else happened. I hadn’t seen her for a couple of days in the Bar of Mirrors. Then I saw her walking along the Salita Pollaiuoli in her own clothes. She said “Ciao” to me. She had a bandage around her left elbow and her left wrist was stained red with iodine disinfectant. There were red patches on her left leg and foot, too. Later I was relieved to see her serving in her neat waitress uniform. Her white shirt was short-sleeved so the bandage and the red patches on her arm were visible to all. The patches on her leg were concealed by her black trousers, but she’d rolled up the trouser leg to her ankle, probably because the seam irritated the wound on her foot too much otherwise. It was clearly visible because she was wearing open shoes. Closed-toe shoes would hurt too much, I was sure of that. I repeatedly ordered drinks from her, and each time I wanted to ask what had happened and whether she was alright. But I didn’t dare. I was worried she’d take the question the wrong way. I was afraid that she’d think of her tall boyfriend with the gel in his hair, that bastard, even though I didn’t see him that night.

I’ve noticed how good friends greeted each other. Imagine this: you’re a fat man wearing a dark blue polo shirt. You’re wearing your sunglasses on the top of your head. You heave yourself up onto the terrace, puffing and panting. With visible reluctance, you go and sit down at a free table as you remove your mobile phone from your trouser pocket all in a single, fluid movement. The waitress comes and asks you what you want to drink. The question is not unexpected but still it annoys you. You stare at the floor and in your mind’s eye run through all the drinks in the world. Each one seems even more disgusting that the previous. Finally you order a Campari and soda with a dismissive gesture. You order it in such a way that it is clear to everyone on the terrace that you understand that you’ll have to order something and you’ll just order a fucking Campari and soda then. After that, you immediately continue messing with your mobile phone, causing you to puff and pant again, meaning: I’m an important man and that’s why everyone’s bothering me, but I hate this damn thing, this phone, if I designed one it would be so much better, but that doesn’t interest me, and, what’s more, that’s how things always go in this country, no wonder the economy’s doing so badly and that it’s unbearably hot. It means: I just got a message from the prime minister but I don’t know how this phone works and I wish he’d leave me alone for a moment and decide himself whether to invade Afghanistan or not, but he’s incapable of it, he can’t even hitch up his own trousers without me. Next the Campari and soda is served. You don’t even glance at the drink, nor at the waitress who brings it. You’re much too busy puffing and panting and not understanding how your own phone works, not understanding how anyone can invent a device that even you can’t figure out. The waitress asks if you’d like anything to eat. You growl something incomprehensibly exotic like: just a small bowl of green, pitted olives with Tabasco on the side. Or: gnocchi with chili sauce, hold the pesto, lemon on a stick. Or: peanuts. Then your friend turns up. He’s happy to see you and particularly happy that he’s not the first one to arrive today and that you’re already there. He shouts, “Ciao!” even before he’s walked onto the terrace and then “Ciao!” again, and then a third time “Ciao!” as he sits down at your table. All this time you don’t look at him. You’re much too busy.

A waitress comes over to him, too, and he orders a drink. You’re just in the process of sending your message to the prime minister and you can’t understand why the damn thing won’t send. Your friend says “Cheers,” but you try the prime minister’s other number first. Doesn’t work, either. You huff and puff. Things are like this all the time in Italy these days. You slap the phone onto the table dejectedly. Only then do you look at your friend and say something like, “If Milan bought Ronaldinho, I could have told you Abramovich would put down 150 million for Kaká. It’s crazy they’re not investing in a center back this season. Crazy!”

The Bar of Mirrors is like a porcelain grotto inside. People walk up and down the inclined street outside. The street goes up to the Piazza Matteotti before the Palazzo Ducale. You might also say that it goes to the Via San Lorenzo or the Piazza de Ferrari. It goes down, too. But not many people dare go that way. You get to the San Donato, the touristy bit, which is alright, but then it begins to rise up again. The Stradone Sant’Agostino is the least adventurous. It leads to the monastery and Genoa University’s Faculty of Architecture and, behind that, the Piazza Sarzano. From Piazza Sarzano you can go back down again to the harbor, the sea. If you really have to. But it’s not recommended. The medieval Barbarossa Walls are in the way. And the small streets that do exist can’t be found on any map. “Small streets” is not a good description, they’re more like staircases or improvised temporary walkways over crumbling stones.

The street that ascends and descends is called Salita Pollaiuoli. If you dare turn right before San Donato, you come out on the Via San Bernardo. As the crow flies it is about another fifty meters or so to the Torre dei Embriaci where there’s a good bar. But just try finding it. I’d be interested to know if I’d ever see you again.

Of course I’ll see you again. I bump into the same people all day, even though the labyrinth stretches from Darsena to Foce, from the sea to the mountains, from the harbor to the highway, from Principe Station to Brignole Station. I’ve asked myself how that’s possible. You’d expect a maze to have been built so that people would be out of sight of each other, so they wouldn’t bump into each other all the time—a maze of this size ought to reduce the chances of bumping into the same people to zero. But now I understand that it’s the exact opposite. People can avoid each other in a city of straight lines with clear boulevards and avenues between home and office, office and gym, gym and supermarket, supermarket and home, departure and destination. The person who knows where he’s hurrying doesn’t notice a thing and is no longer observed. In a city of straight lines, people are like electrons in a copper wire—fast, interchangeable, and invisible. The stream can be measured, but individuals cannot be observed with the naked eye. A labyrinth is precisely the place to encounter other people. You can never find the same place twice. But because no one can, everyone wanders around those same alleyways all day. Some spend their whole lives wandering around here. Or longer. I’m sure I’ll see you again, my friend. It’s impossible to find the same piazza twice or walk along the same alleyway twice, unless you are trying not to.

5.

Today I thought about all the different kinds of girls in Genoa.

Some women don’t fit into any category, that’s true. Like the girl in the Bar of Mirrors. She’s made of different fabric than other girls—the same stuff smiles are made of: pathos and summer days. Her mere existence makes me as happy as a small child, and I imagine myself sobbing against her soft shoulders. We’ll leave her aside then. We’re talking about girls, not the rare epiphany of a goddess.

I used to think were two kinds of girls: pretty and ugly. But in light of my most recent research findings, that dichotomy is no longer valid, although I fear the simplicity of the model will always retain its charm.

Of course there are pretty girls. That’s not the problem. You’d like to sketch them carefully with a pencil. You’d like to skate over their smooth undulations with precise fingertips. You’d like to briefly taste the perfect balance of their curves, lines, forms, and volume with a connoisseur’s tongue. Even more than that, you’d like them to take their clothes off and then not to have to do a thing. They might be like a photo you’d be all too happy to download—perfectly suggestive, or explicitly spotlighted.

Girls like that are the way Milo Manara draws them: hieroglyphs of promise. They’re never not posing, though they don’t even need to pose since they already fulfill every standard just standing there. You’d never actually be able to smell them, never be able to tease them by playing with a minuscule roll of fat, nor lick the sour sweat from their armpits, if only because they’re imaginary, just drawn that way. There is something artificially innocent about them, something oo-la-la-ish. Of course they end up in army barracks without their panties, but that’s just because they happened to be kidnapped by soldiers when they were in the middle of undressing. You get that a lot. But they’ll never ring your doorbell without their panties asking if they can give you a handjob in the rain because they’ve never done that before. They’ll never sit on your silver candelabra without further explanation, then lick your table clean before disappearing on home without saying a word.

Recently I got one of those celebrity magazines free with Il Secolo XIX, full of photos of real Manara girls in little more than bikinis. In the accompanying interviews, they say stuff like, “I love men who are honest”; “My daughter is the most important thing in my life”; “I’ll never have sex if Love with a capital L isn’t part of the picture”; and “I’ll always have a special place in my heart for God.” Seriously, just give me the ugly girls then. At least they understand they have to do their best. Or the pretty girls, but then without the interviews, for God’s sake. Or just the bikini-less ones, preferably captured on film.

I saw a tourist girl at San Lorenzo with her tourist boyfriend. He had a camera, she had pink high heels, a yellow handbag, and a scandalous denim miniskirt. They were Russian, you could see that. I checked it for you just to make sure, my friend: they spoke Russian. He wanted to take a picture of her in front of the cathedral. She protested. She wasn’t looking her best today. But when he got ready to take a shot anyway, she put her middle finger to her bottom lip and her other hand to her crotch. They took dozens of photographs like that: next to one of the lions, then the other, in front of the big door, on the steps next to the tower, and so on and so on. She adopted a porno pose for every shot. She wasn’t particularly good-looking, more shameless than refined. She was bored but not so listless to not realize she’d have to do something for a sexy result. I watched her, breathless. There wasn’t a spark of humor or fun in her poses, no fiery lust in her eyes. She bent her body mechanically for the predictable desires of the photographer and all those future browsers who’d click the thumbnails into a cliché of lust. And that was exactly what was so irresistibly sexy.

You’ve also got women with spunk lighting up their eyes in anticipation. In a manner of speaking. They’re usually too young for their age. Lacey nothings frame their gym-fed, well-baked muscles. Someone like that is dry and unpalatable. She dresses like an unwrapped mummy, like that woman of indeterminate age somewhere in her late forties, with short black hair and skirts that get shorter by the day—the one who pays a neighborly visit a couple of times a day, smiling mysteriously, to Laura Sciunnach’s jewelry shop in the Salita Pollaiuoli, across from the Bar of Mirrors, because Bibi with all the tattoos works there, the perfect Don Juan, whose scorn for women causes them to swoon. She’s ugly, but she walks along the street as though she’d inserted two vibrators before closing the door and stepping out onto the street. She never double-locks the door when she comes home drunk at night. She’s like a hungry keyhole through which she wants to be spied. If only somebody would ravish her, for God’s sake. Dripping with lust, she’d report it to the disbelieving carabinieri half her age in their shiny boots, their shiny, shiny boots. And she’s not that ugly, really. I tried to make eye contact with her. I try to make eye contact with her several times a day from the terrace of the Bar of Mirrors.

On the terrace of the Doge Café on Piazza Matteotti, I saw a girl who had painted a girl on herself. She was Cleopatra behind her own death mask. Or maybe she was someone completely different behind Cleopatra’s mask, the only people who know that are the ones who wake up beside her the next morning, rub the sleep from their eyes, full of disbelief, and begin the difficult process of reconstructing the night before in an attempt to figure out the identity of this pale, unknown lady who has so obviously nestled herself between their sheets. And it’s not until she has restored her façade for hours in the bathroom that they remember. Women like that cost money. They don’t just need lotions and potions but designer clothing for every hour of the day, in line with the fashion of the moment, and a lot of shoes, in particular, a lot of shoes. All of those clothes and shoes are only bought to take off again. But to achieve that goal, they have to be expensive, everyone knows that. Each morning she turns herself into the woman she thinks a woman should look like—as she thinks I want her to look. It doesn’t matter whether she knows what I want or not. It’s more important that she does her best to satisfy her image of my image of her.

The worst are fat American women who are under the misapprehension that intelligence is more important than looks. That’s such a stupid concept. They talk about immigration laws in slow, clear English. She was on the terrace of the Doge Café in front of Palazzo Ducale, too, but she was a misunderstanding. With her tits like burst balloons in a comfy summer dress like a pre-war tent, she had no right to talk about any subject whatsoever. She should withdraw to a dark sitting room in Ohio and sit at her computer with shaking fingers and send messages to Internet forums for women with suicidal tendencies under the pseudonym FaTgIrL. She was eligible for a postnatal abortion. Her mere existence was bad enough. The fact she wasn’t ashamed, that she marred, insulted the elegance of Genoa’s, of Liguria’s, of all of Italy’s Piazza Matteotti with her pontifical presence, and the fact she also thought she had the right to be considered a human being rather than an ugly, fat woman, was repulsive.

Fat women as such aren’t the problem, particularly when they’re blonde. Don’t get me wrong. I’ve been able to treat a few to breakfast in my time, I’ll be damned if it isn’t true. They’re animals. You’ll have the best sex of your life with fat girls, believe me, my friend. If they want to. If they don’t want to, they’re pointless and pathetic. But usually they do want to. They’ll rule your bed like six porno films at the same time. They won’t lie photogenically on their backs and wait for what you will or won’t do with your automatic libido; they’ll ride you until you bleed in the full realization that they have to make amends to be considered women.

There are only two kinds of women: those who understand and those who talk. Those who get the game and understand they’ll first have to make a woman of themselves to be allowed to play, and those who knowingly disqualify themselves with the crazy idea that it’s about something other than the game. That’s the truth, my friend. That’s the truth. And I discovered it. And the game is complicated enough, so don’t come to me with your improvements or complications. You know I’m right. And I’m not a sexist or a racist. Exactly the same rules apply to black women as far as I’m concerned.

The ideal women are men. In their attempts to become desirable women, they have to exaggerate. As a parody of sexy women, they transform themselves into inflatable dolls of tits and erectile tissue, and that’s exactly what’s so sexy. They know exactly what they’re there for—but women like that don’t exist. Although I have seen them on occasion down by the harbor, on the roadside near the Soprealevata highway’s exit ramp. And later I saw two more near the Palazzo Principe train station. But I’ve forgotten where and have never been able to find them there again, nor near the harbor. Maybe I keep going back at the wrong time.

6.

But in the meantime, the fact was that I had an amputated female leg in my house. Although I needed to come up with a solution as fast as possible, of course, in any case before it began to smell a bit funky, it was also exciting in a peculiar kind of a way. I went home earlier than usual. But I didn’t take the leg out of the cupboard. I could spend hours thinking about not doing things like that. And then I thought of something. Was it true? Yes, it was true. Was I sure? I was sure. I’d only touched the stocking. I hadn’t touched the sexy bit of naked thigh above the garter. I certainly would have remembered how that felt. I was immediately grabbed by an almost irrepressible urge to do it anyway. But that wasn’t the point. I realized that I could get rid of all the fingerprints and traces of DNA by taking off the stocking.

It was a sensible plan. No, it wasn’t exciting; it really was a sensible plan. The best plans are. Exciting and sensible. In inverse order, but in this case that didn’t matter. It didn’t matter in any single case, except for the fact that the question whether something was exciting or not almost always takes priority and the question whether it’s sensible or not usually tends to get pushed to the background, at the most being claimed retrospectively, as a means of justification, which is not really that regrettable given that this all too human mechanism contributes significantly to the preservation of the human race.

I was raving, I know I was. I was nervous. I opened my bedroom wardrobe. As though I was removing an easily broken ivory artifact from a safe with white gloves to allow a scholar, who had traveled from afar, to study it, or as though I was scooping a delicate, fragile algae from the surface of a forgotten, glassy lake of unfathomable depths—that was the way I took the leg from the IKEA wardrobe and laid it on the table. In other words, slowly and carefully. The pompous comparisons are only intended to maintain the tension. Well, not only. With a bit of good will, they also evoke the reverent trembling of my hands.

I stroked the curves of her foot, her heel, instep, and ankle. I gently pinched each toe. “You have such tiny little toes,” I said. She began to laugh. It tickled. The back of my hand slid along her shin. The jagged edge of a nail caught in her stocking for a moment. “Sorry.” I followed the soft lines of the subtle contours of her knee with my index finger. I let my hand descend to the tender, vulnerable skin of the back of her knee, where I lingered a while so I could summon up the courage to take her whole calf in my hand. The bulging muscle filled my reverent hand like a breast. Shapely yet bashful, firm yet soft, sturdy yet cute, she was light in the palm of my hand, which she perfectly filled. We were made for each other. “You probably say that to all the ladies.” I didn’t reply. I moved my hand excruciatingly slowly up along the inside of her leg to her thigh. She began to moan. “What are you doing?” she whispered. But I wasn’t doing anything. I teasingly tugged at her garter with little, absent-minded, detached movements. And then I climbed the sloping mound of her thigh muscle. I let my fingertips and my thumb rest in the shallow, barely noticeable hollows on both sides. I began to knead, gently and carefully. She liked it. She made growling noises like a purring cat. And as my hand crept farther and farther upwards, like a hungry animal, she began to moan more and more loudly.

I stopped abruptly where the stocking ended. With a surgeon’s precision, I took the garter band between the thumb and index finger of each hand and, without touching the skin, peeled the stocking slowly from her increasingly bared leg. I denuded her copper thigh, her round, funny knee, her mirror-smooth shin and her cheekily rounded calf, her chiseled ankle, where I faltered for a moment to change direction and finish my work with an elegant maneuver by which I freed her heel, her curved instep, and her giggling toes. I laid the stocking next to her on the table. She shivered but not from the cold. The minuscule, scarcely visible blonde hairs were now standing on end. She sighed deeply and moved her leg to the side to allow me access. “Please,” she whispered. I kissed her mouth and came.

7.

And that was how I ruined everything. Fuck, what a moron I was. A big blob of my sperm on an amputated woman’s leg. That was exactly the kind of DNA the CIA folks liked best. With the certainty that a man was involved in the unsavory affair, and the bonus of quite a big hint as to the motive. And then to try coming up with the excuse, in the face of such persuasive evidence, that you’d just happened upon the leg in the street during a storm-induced power outage, and that that blob was only there thanks or no thanks to the fact that she had moved her leg aside with a sigh, after I’d carefully taken off her stocking, and had whispered that it was alright. “But you must believe me, your honor, I swear to you, that’s what happened.”

I live in my imagination too much. And look what comes of it. Problems come of it. Sperm on a ripped-off, rotting limb comes of it. What a fine mess I’d gotten myself into. How humiliating. How could I have let myself get carried away like that? Of course it’s also part of my job to represent the thoughts and motivations of others as vividly as possible and if necessary, to create characters from nothing, characters onto whom I can project myself so vividly that they become flesh and blood, allowing me to set down a convincing portrait of them on paper. But that doesn’t mean that when I’m not holding a pen, I should start believing in my own delusions and consider one leg sufficient to project the rest spread-eagled onto it, breathe life into a whole new willing mistress and throw myself, panting, upon her. That would get me into another fine mess. Worse, it already had.

I decided I had to get rid of the leg as quickly as possible. But first, of course, I had to give it a thorough cleaning. Naked skin is easy to wash, easier than skin clothed in nylon. That was what I told myself as I tried to apply some kind of logic to my actions and retrospectively give the stocking striptease a rational justification. I put the leg in the shower. It was a strange kind of automatism, if I can use that word for something I’d never done before and, with a probability bordering on certainty, would never do again. All things considered, it was an object and you washed objects in the sink, but clearly I thought legs belonged under the shower, as though there were still a woman attached to it.

And then I realized that I’d miss her. I undressed and got into the shower with her. But that was only intended as a sweet gesture, like having a shower together after sex. I washed her gently, carefully and attentively. It was our farewell. After that I got a garbage bag and pulled it over the leg without touching the freshly-washed skin or leaving any evidence. I tied the bag tightly shut, got dressed, went outside and threw the bag into the builders’ dumpster. Sure enough, I felt a little sad.

8.

Come si deve. If there’s a concept that characterizes and unifies Italy (in so much as that exists), it is this life philosophy that everything has to be the way it should be, come si deve. Of course everyone has different ideas about that—how things should be—but everyone does agree that it must be as it should be, not necessarily because that’s good, but because it has always been that way. The most obvious example is food. Each region, each province, each city, each quarter has different ideas about how spaghetti al ragù should taste. They even call it different things. But everyone agrees that it should taste like it has always tasted. A chef ’s creativity is not appreciated. The chef should be a craftsman like a cobbler, not an artist. The chef, like the best cobbler, doesn’t spring any surprises on you. That’s why you always eat so well in Italy. And that’s why they have such nice shoes.

But that’s what all of life is like in Italy, from the cradle to the grave. You’re born, grow up, get married and leave home, have children who leave home when they get married, and you die. You celebrate Christmas at Christmastime and eat roast lamb at Easter. You go to the seaside in August. All the shops will be closed. In Genoa, it’s an entire month of scarcely being able to buy the bare necessities. There are only two tobacconists open in the whole city center, one newspaper kiosk, and one liquor store. If you’re lucky. And just try to find them. Bewildered tourists wander around among the closed shutters. The mayor calls for legislative measures, and rightly so, but just try to do anything about it, because everyone goes to the seaside in August and not in June or July, which would be much more sensible since at least there’d be a place on the beach and everything would cost half what it costs in August. But that’s not come si deve.

It is life according to a liturgical calendar of recurrent, annual family parties, family outings, birthdays, name days, home and away matches, qualifying rounds and finals. It’s a spiral that ends after seventy or eighty rotations with a memorial plaque on the gray walls of a church, formulated and designed like all the other memorial plaques. We look back with pride and gratefulness at a rich and full life that progressed just like other lives, in the same streets, on the same squares, in the same houses, and on the same beaches, with breakfast at half past seven, pranzo at half past twelve, cena at nine o’clock, blessed with children and grandchildren who will do everything exactly the same. Stanno tutti bene. Tutto a posto. Come si deve.

I’ve seen a woman who was exactly like that. I see her all over the place because she’s always at the right place at the right time. She has breakfast at Caffè del Duomo on San Lorenzo. She lunches at Capitan Baliano on Matteotti. At six on the dot she comes into the Bar of Mirrors for an aperitif. She has a glass of Prosecco and then, why not, another glass of Prosecco. She always says that as she orders it: “Oh, why not, another glass of Prosecco.” As though it were an exception. And she’ll never order a third glass of Prosecco. She always says that, too: “I never have three glasses of Prosecco as an aperitif. Two is enough for me.” She’s an exemplary Italian in every way. I couldn’t imagine her in any country but Italy. She’s so come si deve that outside of Italy she’d wither and die like a tree that had been transplanted out of the specific, precious microclimate of its natural habitat. On Saturdays she meets her friend on the square at exactly the right time on exactly the right day at exactly the right place to eat pizza. She is exactly fifteen minutes late for the meeting and her friend is exactly fifteen minutes later than she. They then have a fixed ritual of apologies from the lady who’s too late, resolutely waved off by the lady who was less late. It’s a stainless steel routine that’s repeated to the second, time after time, week after week, year in year out, generation after generation.

Two days a week, she has her granddaughter, a notorious redheaded diva of about three years old. She’s called Viola. I know this because that’s what everyone keeps calling her. Her, too. Each time the little girl does something, it doesn’t matter what—climb up onto her lap, climb down off her lap, walk in circles around the parasol stand, stir the Prosecco with her finger—she says, “Viola, don’t do that!” As an aperitif she gets an acqua frizzante with a straw and a bowl of patattine—what do you call those again? Fries? Then she says, “Look, Viola! Here’s Viola’s aperitif!”

The most beautiful girl in Genoa, who works at the Bar of Mirrors, is besotted by Viola. She kisses her, strokes her red curls, cuddles her, and babbles away endlessly to her about the fries, about her new shoes, about the color of the straw, pigeons, parasols, freckles, dancing, and the bandages on her cuts and scrapes that haven’t healed yet. It’s astonishing. It’s a holy miracle to witness. The magic of the fairy-tale harmony between a little tyke and a good fairy. The most beautiful girl in Genoa should be as unapproachable as a glimpse of an image you catch in a mirror, but before my very eyes she turns into the most endearing essence of approachability. The old lady watched with the smile of an Italian grandmother who found it only natural that her granddaughter should be adored by waitresses. I decided to speak to her.

I loved speaking Italian. I wasn’t very good at it, but I liked to, which seems to me to perfectly fit the definition of an amateur. Whenever I was on a roll, or at least thought I was, it felt like swimming in the waves of a warm sea. I could bob on the rhythm of the long and short syllables. I would stretch myself out on long, clear vowels and then make a playful, thrashing sprint across the staccato of consonants. I’d dive down into a daring construction, knowing I’d need a subjunctive sooner or later, but would come up spluttering. It didn’t matter what it was about or whether it was about anything. It was a game. I didn’t need to swim anywhere; it was enjoyable enough just to be in the water.

Although I loved Italian and tried my best to learn it, I didn’t really take it seriously as a language. It’s a language for children, a language that tastes of rice with butter and sugar. The language is perfectly suited to a month at the seaside in August with the whole family, when the world can be easily organized and divided into clear categories like bello and brutto, buono and schifoso, libero and occupato, pranzo and cena. The language is also exceptionally suited to shouting at children the whole damn day that they shouldn’t do that, whatever it is they’re doing, and to say that’s enough. You can also say goodbye to each other the whole day in it. It’s a language that makes a racket and that’s the only thing that counts, like when children are happy, weeks-on-end happy, drive-you-crazy happy with a rattle.

But I was, too. I was happy. I wanted to make a racket. And the fact, the more than obvious fact, that I had to practice and improve my Italian gave me a wonderful excuse to address complete strangers on any random subject. I would never do that in my own language because those people don’t interest me, let alone what they have to say, and because my own language isn’t a toy. And if I accidentally say something insulting in Italian, I can always add a few grammatical blunders and then sit there smiling naively like a screwball foreigner. I could get away with anything—that was what was so fun about it.

So that was how I spoke to Viola’s grandmother. She was so Italian and so come si deve I thought she’d prove entertaining training material.

9.

“My name is Franca. But it’s better that you call me Signora Mancinelli and use the formal mode of address because you have to practice your Italian and the formal modes are more difficult. And you? What? Giulia? Giulian? Gigia? Leonardo. That is a bit easier, indeed. Like Leonardo da Vinci. I can remember that. Or, if you asked today’s youth, Leonardo DiCaprio. I’m an elderly lady of the upper class. They still had education in my days. I know who Leonardo da Vinci was. See that man over there? Look hard.”

He sits on the terrace at the Bar of Mirrors almost every day, a bon vivant, suffering from some subsidence, who acts too young for his age. He has white hair and wears brightly colored Hawaiian shirts from the plastic boxes of remainders at the market. When he comes shuffling along with his plastic bags from the Di per Di, he looks like a tramp. But once he’s sitting down he orders a mojito. Tramps don’t drink cocktails. And he has plenty of chitchat. Everyone who says hello to him is treated to an undoubtedly priceless anecdote, freshly plucked from the riches of his daily life. He bares his teeth as he smiles and draws passersby and waitresses into his monologue. He wears glasses on his forehead, which are supposed to give him the air of an elderly intellectual. But I don’t fall for that. He has holes in his shoes. His eyes are deep-set, his cheeks have caved in, and his stubble sticks to his chin like the frayed edges of an unwashed bathmat. He nods briefly at fellow tramps passing by over the gray paving stones.

“Watch out,” the signora says. “He’s a very important man. Bernardo is his name, Bernardo Massi. He’s rich.” She leaves a meaningful silence. “Very rich. Although they say his wife left him. But I know he still has a palazzo on the Piazza Corvetto.” I nodded to show I’d understood how significant that was. I tried to get a better look at him but some tourists had sat down at the table between him and me. They were seriously blocking the view with an excess of cameras and sticky body parts, peering at a map. The waitress came and they ordered a beer and an iced tea. The waitress asked whether they wanted anything to eat. They have the charming habit here of serving a range of snacks with the aperitif, with the compliments of the establishment. But the tourists became acutely suspicious, suspecting it was a dirty trick to make them pay for more than the two drinks they’d ordered and which would certainly be too expensive, here right in the center, and you know, you have to be very careful in these southern countries because they’ll rip you off right in front of your nose, and in any case we’re never coming back here, it’s much too expensive, but why am I fussing about it, are you fussing about it, we’re on holiday, so we’d better enjoy it, otherwise you don’t really have a life do you, that’s what I always say, it’s pretty important to enjoy yourself in life, even on holiday, so let’s just drink our drinks.

I don’t know whether it’s shamelessness, indifference, or a cultural code. But why in God’s name do tourists have to wear their dirty underwear as soon they sit down in a southern country and block my view? He was wearing a stained t-shirt from a German football club and shorts that had been washed to shreds; she was wearing comfy, baggy holiday shorts. They looked like intelligent, wealthy people to me. No doubt they had a house in Dortmund and a delectable DVD collection in their designer shelving unit, a car with fancy wheel trims in the garage, and evening wear for their work’s New Year’s reception in their recessed wardrobe.

In the Pré quarter, where Rashid lives along with the rest of Africa, every underprivileged illegal immigrant spends the first sixty euros he earns on a fake Rolex with imitation diamonds so that he can begin to fit in a little bit with the respectable Europeans, and those heirs of the wirtschaftswunder were just sitting there in their underwear. What kind of an impression do you think that made? And what do you think it means? What did they mean to say by this? If you’re on the beach by the Deiva Marina or at a campsite in Pieve Ligure I can understand it. But this was right in front of my view, on the most precious terrace in the city, in the shadow of centuries, in the historical center of Genoa, La Superba, the heart of the heartless one that had allowed them to penetrate to the roots of her pride. Does it mean they don’t understand or they don’t want to understand? Or are they sending out a special message? Like: We just happen to be on holiday here, nice to get away from all the stress, and that’s why we’re doing what we want, just having a lovely nice time being ourselves for those three weeks a year, you know. Or: Those Italians don’t know a thing, it’s just one big hip-hip-hooray beach from the Costa Brava to Alanya. Or is it actually intended as a status symbol dressing like that, does it mean you can permit yourselves to go on holiday without caring about anything whatsoever?

“Don’t be fooled by appearances,” the signora said.

“My apologies, signora, I was distracted for a moment.”

“He looks like an unmade bed. He dresses as though he has shares in the illegal sewing shops in the Pré. It wouldn’t surprise me if he did. I must ask Ursula some time.”

“Who are you talking about?”

“Ursula Smeraldo. She has a countess in her family. By marriage, though. And just between you and me, she’s rather down on her luck, if you get my meaning. But we’re practically neighbors on the Via Giustiniani, and it would be strange if I didn’t greet her. What’s more, she knows what’s going on.”

The tourists’ shamelessness reached a new low. They’d unfolded their map and asked the waitress where something was. They had the goddamn guts to speak to her! Probably about something ridiculous like the aquarium. She stood bent over their table for minutes on end, giving them all kinds of explanations. My waitress. She was sacred. No one can ask her the way to the aquarium in their underpants. She’s not allowed to reply, and certainly not so extensively and sweetly and prettily. Not so sweetly and prettily. Not so extensively. Not so bent over and so much in my line of vision it hurt.

“I know about her, too.”

I gave the signora an irritated look.

“Ursula told me that Bernardo Massi broke up with his wife. But everyone knows that he’s powerful and important, that he’s rich, I mean, even though he dresses like a tramp. Don’t be fooled by the exterior. Everything is hidden in Genoa. We don’t have any squares with fountains, no palazzi with fancy façades. All the gold and art treasures are hidden away behind incredibly thick walls of common gray limestone. A true businessman stashes away his fortune in an old sock and goes out onto the street wearing tatters in the hope of receiving alms. In Milan and Rome, everyone wants to show off everything, fare bella figura, with a flamboyant display of good taste and excess. In Genoa everyone understands that it doesn’t give you an advantage. To the contrary. The man who splashes his wealth about ostentatiously has far too many friends, as the saying goes. The saying is a bit different from that, but you understand what I’m saying. Do you understand what I’m saying? You have to learn how to behave in this city. It’s a porcelain grotto.”

“I think I can only see the exterior,” I say. Only then did the waitress turn around. She asked us whether we might like something to eat. She asked it coolly, unapproachably, and proud, like someone with a countess in her family, like the marble duchess herself—La Superba.

10.

If I think about these notes, my friend, and think about how I’ll turn them into a novel someday, a novel that needs to be carried along by a protagonist who will sing himself free from me and insist on the right to his or her own name, experiences, and downfall in exchange for my personal confrontation with my new city, which is more like a triumphal tour than a tragic course toward inevitable failure—and, on the grounds of that alone, is not suitable material for a great book—then I think about how crucial it will be to make tangible sense of the feeling of happiness that this city has given me time after time, even if only as a sparkling prelude to the punches of fate. Happiness, I say. I realize you could no longer repress a giggle when I said that. I realize that it’s strange to hear such a weak and hackneyed word come out of my mouth. Happiness is something for lovers before they have their first fight, for girls in floral dresses at the seaside who don’t see the jellyfish and the ptomaines, or for an old man with a photo album who can no longer really tell the difference between the past and the present. Happiness is basically a temporary illusion without any profundity, style, or class. The candy floss of emotions. And yet, for lack of a better word, I feel happy in Genoa, in a golden yellow, slow, permanent way. Not like candy floss, but like good glass. Not like a carnival, but like a primeval forest. Not like the clash of cymbals, but a symphony.

It is also remarkable, or I daresay unbelievable, that happiness is dependent upon location, on longitude and latitude, city limits, pavement, and street names. I’ve read enough philosophy, both Western and Eastern, to realize that wisdom dictates you should laugh at me and dismiss my sensation as an aberrance. So be it. That’s the point. The more I think about it as I write these words, the more I become convinced of the importance of putting into words this impossible, undesirable, unbelievable feeling of happiness.

Street names and pavement. That’s the way I formulated it. In the first instance as a stylistic device, of course, sketched with the rough sprezzatura that characterizes my writing. But in the second instance, it’s true, too. I’ll give you an example: Vico Amandorla can make me so happy. It’s an insignificant alleyway that runs from Vico Vegetti to Stradone Sant’Agostino. It’s a short stretch, and you don’t encounter anything of any importance along the way. The alleyway isn’t even pretty, at least not in the conventional manner. Normal, ugly old houses and normal, smelly old trash. But the alley curves up the hill like a snake. A little old lady struggles uphill in the opposite direction. The alley is actually too steep, built wrongly centuries and centuries ago or just sprung into existence in a very awkward manner. The alley is pointless, too. You come out too far down, below the Piazza Negri. If you want to be there, at San Donato, it’s much better to just take Vico Vegetti downhill and then turn right along Via San Bernardo. That’s faster and more convenient. And if you want to be in the higher part of the Stradone Sant’Agostino, at Piazza Sarzano, it’s much quicker and more convenient to follow the same Vico Vegetti in the other direction, past the Facoltà di Architettura straight to Piazza Negri. All of this makes me very happy. And then the pavement. This alley isn’t paved with the large blocks of gray granite you get everywhere in Genoa, but with cobblestones as big as a fist. You can’t walk on them. There’s a strip of navigable road laid with narrow bricks on their sides. Half of them have sunk or come loose. There hasn’t been any maintenance here since the early Middle Ages. And then that name. Who in the world wouldn’t want to stroll along Vico Amandorla? It’s a name that smells like a promise, as soft as marzipan, as mature as liquor in forgotten casks, in the cellar of a faraway monastery where the last monk died twenty years ago one afternoon with an innocent child’s prayer on his lips in the cloister gardens, in the shadow of an almond tree, as happy as a man after a rich dinner with dear friends. Say the name quietly if you are afraid and you won’t be afraid anymore: Vico Amandorla.

From Piazza Negri you can walk, during museum opening hours, through the cloister gardens of Sant’Agostino to Piazza Sarzano and the city walls. The passage through the cloister is triangular, undoubtedly as an architectonic compromise with exceptional topographical circumstances. The tip points toward the tower, which is sprinkled with colorful mosaics that clash with the strict and sober gray of the cloister. What’s the statement? What must the monks who wore away the pavement of the cloister passage with their footsteps have thought at the sight of their own festive tower? That it was Mardi Gras outside? That the gray life in the cloister clashed with that path upwards to heaven, a path as garish and variegated as a rocket, ready to be fired so that it can burst out into a cascade of colors?

Piazza Sarzano is a square that I still don’t really get, a square like a formless mollusk with a Metro station I never see anyone going into or coming out of. But just to the right of it, left of the church, is a secret passageway to another city—a medieval wormhole. With its profound and contented pavement, the street swings steeply up the hill to a forgotten and abandoned mountain village straight out of Umbria or Abruzzo. A handful of narrow, abandoned little streets that rise and fall around a shell-shaped village square that slumbers in the sunshine. But in the distance you don’t see any mountaintops, no hills crosshatched with vines, no goatherds, but the docks of Genoa. This is a magical place you cannot be in without realizing that you actually can’t be there because the place cannot exist. This is Campo Pisano, a perfect name euphonically, an ideal marriage between sound and rhythm. Its meter is the triumphant final chord of a heroic verse. The name fits perfectly after the bucolic diaeresis of the dactylic hexameter. The succession of a bi-syllabic and tri-syllabic obeys the Gesetz der wachsenden Glieder and creates a charming auslaut after the first unmarked element of the dactyl, by which an ideal alternation between a falling and a rising rhythm arises. The sound is carried by the open vowels that shine like the three primary colors on an abstract painting by Mondrian. The falling movement from the a to the o finds a playful counterpoint in the high i before it is repeated.

The cool hard consonants articulate the composition like the black lines on the same painting, with the racy repetition of the p right in the middle. It is a name like an incantation to evoke a magical abode. A spell of otherworldly sophistication is needed to bring to life an impossible place. If someone were to unscrew the street’s nameplate from the wall, Campo Pisano would vanish into the mists of the docks, only to reappear when an ancient high priest remembered the name and it passed through his wrinkly lips between the Barbarossa walls and the sea. Campo Pisano. It’s a happy place with a tragic past, in the same way that only people who have known pain can be happy because people who are painlessly happy like that blow away like a Sunday paper in the wind of an early day in spring. This place was once a kind of Abu Ghraib. Prisoners of war were locked up here after La Superba’s army and navy had finally put down their archenemy Pisa for good. The curses of the defeated and humiliated Pisani still ring out to this day. Symbols of Genoa’s power are worked into the pavement in mosaics made of uneven pebbles. I’m the only person about at this time of day. The green shutters on the houses are closed. The wine bar won’t open until the evening. In the distance I can hear a goat bleating, or a ferry honking.

Vico Superiore del Campo Pisano is a dead end, but Vico Inferiore del Campo Pisano isn’t. Or the other way round. It depends which day it is. One of the two of them is a new wormhole, not back to Genoa and the present, but to America and yesterday’s future. The road curves gently downhill to the left and leads to a grotto. Dampness and vegetation seep from moldy walls. These are the vaults of the bridge that links Piazza Sarzano with the Carignano quarter. The high priest lives under the last arch. His skull is older than the city. High above him, the people of Genoa go in search of parking spots and bargains. Closer to the sea the fast traffic races along the Sopraelevata, the raised motorway along the coast.

The grotto opens out into a post-apocalyptic landscape, or to be more precise: this is the perfect location to film an old-fashioned science fiction film, preferably in black and white. Its official name is Giardini di Baltimora, but people know it as Giardini di Plastica, the plastic garden. It’s a gigantic dog-walking spot that also serves as a shooting-up area for heroin addicts and a kissing zone for young couples without places of their own. It looks like a 1960s or ’70s version of the twenty-first century. Desolate green with charmingly gray mega-office-blocks. Above-ground nuclear bunkers in a field of stinging nettles. Pre-war spaceships that have crashed in a forgotten hole in the city and gradually been reclaimed by nature.

All kinds of pathways go back up to the Middle Ages from here, or to Piazza Sarzano or Via Ravecca. But you can also walk under the supports of the rusty behemoths, across the underground car park beneath which the motorway runs to the sea, past peeling bars and clubs with unimaginative names, under the skyscraper, to Piazza Dante. The city will reveal itself to you there once again, with an ironic smile. Yes. After your epic journey, you’re simply back on Piazza Dante. Thousands of Vespas, Porta Soprana, Columbus’s house, the cloisters of Sant’Andrea, in the distance the fountain on Piazza de Ferrari and, on the other side, Via XX Settembre. You know every street here. It’s just a three-minute walk to your favorite bars. You burst out laughing in surprise. But how am I ever going to write about this, my friend? How can I ever make people believe that a city makes me happy?

11.

Religion is the opiate of the masses. Although Italy has flirted more often and more intimately with Marxism than most other Western European countries, it is one of the most drugged up countries I’ve ever seen. The Holy See actively gets involved in politics. The pronouncements of the Holy Father are even widely reported in progressive and left-wing newspapers. Not a week goes by without a public debate that is only a debate in that the Vatican has regurgitated one of its anachronistic opinions in a press release. There are few politicians who have the courage to commit electoral kamikaze by distancing themselves from the dictates of the Holy Mother-Church or casting doubt on the authority of the old right-winger who believes himself Christ’s terrestrial locum.

Genoa is a civilized, northern, and even explicitly left-wing city, where money is earned, where people can read and write, and where all the old people go to church. Or they take communion at home if they live on the seventh floor, with their fluid retention and their walker and the lift’s out of order again. The tabloids scream outrage. In Genoa, a salesman’s healthy skepticism is the norm, just as the pleasant shadow in the alleyways doesn’t evaporate under any amount of sun. Jesus said that Peter wanted to build his church on a rock. Peter’s church in Genoa is on Piazza Banchi and it is built on shops. The foundations of trade still lie under the church’s foundations. But even here, the mayor only has to come up with the idea of organizing a Gay Pride parade for the archbishop to put a stop to it the next day.

Being a Catholic doesn’t have to be a conscious choice, not like the existential struggles in Dutch Protestantism that go with being doubly, triply, quadruply Reformed or Restored Reformed. In the fatherland, conversion to Catholicism is for men of my profession worthy of a press release, guaranteed fodder for an endless series of discussion nights in community centers. In Italy, it’s something you’re born into, just like being born a supporter of Genoa or Sampdoria, and just as you’re born someone who eats trofie al pesto and not egg foo young with noodles. God isn’t someone you search for on a hopeless path with your hands cramped into a begging bowl, but someone like the coach of a football team or the chef in a restaurant: he’ll be there, and no doubt he’ll do his best, because that’s how it’s always been. So you get baptized and you marry in a church, not because you particularly want that, but because it makes Granny happy and because that’s the way it’s always been. Catholicism is the default, the standard setting, and too many complicated downloads and difficult processes are needed to deviate from it. Most people won’t go to all that trouble.

But this wasn’t what I intended to talk about at all. Religion is a bit of a woman’s thing after all. The men in Italy celebrate their own holy high mass every Sunday at three o’clock on the dot. Since time immemorial the year has unfolded around the cycle of friendly duels and preliminary rounds that lead to the championship and the final position. The religion is called Serie A. Mass is each team’s weekly match. At three o’clock on Sunday afternoons, millions of Italian men sit in their regular parish to be flagellated for ninety minutes by the live coverage on Skynet or some other subscription channel. Sampdoria’s church is the Doge Café on Piazza Matteotti; Genoa’s church is Capitan Baliano, diagonally opposite. At halftime during the service, everyone smokes a fraternal cigarette together on the same square before returning to their own temple at exactly four o’clock for the second half and another forty-five minutes of suffering, hell, and damnation.

Nobody enjoys it, as befits a religion. I’ve watched a football match in a bar a few times back home. You have to drink a lot of beer and do the cancan together, and by the second half getting beer down each other’s throats becomes more important than watching the match. In Italy, on the other hand, it’s a deadly serious matter. The men drink coffee and swear.

There isn’t a single Italian male who doesn’t know about food. He can’t cook, his wife does that, but he knows better. It’s his job to deliver negative comments about each course in an indignant manner. And there isn’t a single Italian male who doesn’t know about football. He’s incapable of sprinting fifty meters, but he knows better. Each Sunday it’s his job to give an indignant and scornful commentary of every move made by the top athletes in the stadium.

But Italians don’t know a thing about football. They don’t understand it and they don’t even like it. Every time a player loses possession it’s the referee’s fault for not spotting a foul. Each goal conceded is proof of the scandalous inferiority and the appalling ignorance of the opponent who has gone and gotten it into his thick skull to score against their team. They cheer if a player on their team brings an adversary down with a violent tackle and jeer when the referee penalizes this action. And, in general, even with the best will in the world, no one can understand how, these days, the best-paid top players constantly make the most basic fuck-ups. The game is mostly unwatchable, because when Italian clubs compete with each other, they never take a single risk, and their lineups only have half a striker.

It’s the same every Sunday. No one takes any pleasure in it. But they wouldn’t miss it for the world. It’s ritual. The week exists by the grace of Sunday afternoons. It wouldn’t surprise me if the same match had different results in different parts of Italy. On the Genoese subscription channels, Genoa beat Palermo 4-0, after which an orgy of pretty things you can buy if you’re happy explodes onto the screen. Palermo probably won the same match 4-0 on the Sicilian subscription channels.

Like every religion, Serie A has a gospel. But it’s much better than those four books in rotten Greek the Vatican’s had to make do with for centuries. It’s printed on pink paper and appears daily with new messages of salvation every time: the Gazzetta della Sport makes it possible to lose yourself in fantasies about Sunday afternoon all week long, with retrospectives that are updated daily, prognoses, statistics, and charts. You don’t need any other newspaper if you want to be an Italian among the Italians. Tutto il rosa della vita is its slogan—everything pink in life. The world’s fucked, hundreds of thousands of poor bastards are landing on Lampedusa, the government has declared a state of emergency, there are soldiers in the streets, and people are dying of poverty, but if you read the Gazzetta dello Sport, none of that has to bother you. There, it’s just about the things that are really important, like the percentage of risky passes from the left wing in comparison to the 1956–57 season.

Italy lives in its imagination. The opium of its people is pink.

12.

I often thought back to my short and confusing relationship with the leg, or rather with the girl I’d fantasized onto it. I was ashamed. But I had to get over that. In a certain way, it had been perfect love. Because I’d dreamed her up myself, she was the woman of my dreams. And yet she was concrete, material and physical enough to have me believe that I wasn’t dreaming. I could actually touch her, stroke her, feel her, and she moved, sighed, and groaned exactly as I imagined in my loveliest fantasies.

The problem with complete women is that they can interfere with your fantasies. There’s a good amount of body to grope, but in fact you do exactly the same thing as when there’s only a single leg available to you. You quench yourself with her skin, while her melting thoughts become your thoughts. You moan sighs into her mouth. You create an image of her and expect her to live up to it. The more she manages to match your unspoken fantasy, the better she is.

Good sex is the illusion that the other finds your lovemaking good. Love is like a mirror. You see your own countenance in the delighted face of the other. You hope the other sees herself reflected in you, while you project your own longings onto the emptiness of her astonished eyes. I mean: everyone finds true love sooner or later. But there are at least six billion people on earth. How probable is it, statistically speaking, that the collection of limbs lying next to you in bed happens to be the one unique person who makes your existence complete? How likely is it that “The One” should drop onto your lap like a snow-white dove who has died in midflight right above your beseechingly outstretched hands? True love is the decision to start believing in the fantasy at hand, instead of fantasizing. My love for the leg was exactly like that. All things considered, it was exactly like that. Do you understand?

And unlike an un-fabricated girl with a mouth in a face on a head atop shoulders that has a mind of its own, my mistress could say nothing that impeded the illusion. She was perfectly identical to the image I’d made of her. And so she remained a concept, a work of art, the snow-white dove I could catch wherever I wanted her to fall. When I had sex with her, I had sex with my own fantasies, and so the sex was perfect. Because that’s how things are. Because every encounter is accompanied with wild assumptions about what the other is thinking, with her trembling little shoulders and her eyes so brown in the headlights of your rampant lust. At night, the other looks like the unlit motorway to the embodiment of your unclear dreams, but you haven’t realized that as you honk with your dimmed headlights, she is driving even faster toward an uncertain destination behind you. And after the head-on collision, once perfect limbs dangle off sharp edges of broken glass. I know you understand me. You’re not like the others.

And after having spewed out all of my so-called wisdom, you’ll also understand how stupid I was. It’s all about the garbage bag, dummy. You can fantasize as much as you like and have a nice shower, but if you go and casually wrap an accommodating, pristine, gray piece of plastic around her leg with your desirous sweaty fingers, you’ll leave impeccable fingerprints behind. She was still there. I carefully lifted her out of the garbage can and brought her back home with me.

13.

The butcher was a redheaded girl. She was wearing a white apron and sky-blue clogs as she pulled up the shutters. The metallic rattle spread like whooping cough through the neighborhood. The hours of the pranzo and siesta were over. The city went about its business, hawking and sighing. A street-cleaning vehicle from the sanitation department drove through the narrow streets with a noisy display of revolving brushes, sprayers, and vacuum cleaners, streets that were impossible to get clean after all those centuries. The vehicle was driven by a woman with a generous head of black curls and a formidable hook nose. Maybe she had an excellent sense of smell and that was why she’d been chosen for the job. She couldn’t get through. A beggar was lying on the street, refusing to get up; of course it was the dirtiest place in the greatest need of a clean. She got out, swearing. She was small, wearing a baggy green uniform. And when the tramp still didn’t react, she gave him a nasty kick. Yelping like a dog, he retreated under an archivolto.

“This is a city of women,” the signora had said to me a few days previously. “You have to understand that.” She’d appeared out of nowhere, as usual, around the San Bernardo in a long elegant dress and with a thin cigarette between her fingers. “A city whose menfolk are always at sea is ruled by women.” I said it was better that way, but she disagreed with me in no uncertain terms.

The cleaning truck carried on, leaving behind a trail of slime made up of half-aspirated, wet trash. A drunk Moroccan smashed a beer bottle. Someone threw a garbage bag onto the street from the fourth floor. At night, the rats have the place to themselves, but they’re not only around at night. This is Fabrizio De André’s street, which he sung about as la cattiva strada, the shit street, Via del Campo. With bright red lipstick and eyes as gray as the street, she spends the entire night standing in the doorway, selling everyone the same rose. Via del Campo is a whore, and if you feel like loving her, all you have to do is take her by the hand.

“Maestro, how are things? Terrible as usual?” It was Salvatore, the one-legged beggar. He’s from Romania, but he’s become welded to this city. Everyone knows him because there’s no escaping him. He knows how to find everybody. He speaks a kind of universal Romance language—a mixture of Romanian, Italian, Spanish, a couple of Rhaeto-Romance dialects, and a handful of Latin words. “One-legged” is the wrong word. He has both his legs, but when he’s begging, he rolls the left leg of his trousers up to his thigh to expose an impressive scar and then he struggles around with a crutch, as though that rolled-up leg no longer worked. I’ve seen him after work in the evening with both his trouser legs down and the crutch under his arm, running to catch the last bus. But from time to time I give him a coin. He’s a street artist. He amuses me.

“I’m sorry, Salvatore. I don’t have any change today.”

He gave me a friendly pat on the shoulder. “Don’t you worry, maestro. You’re my customer. You can pay me tomorrow instead.”