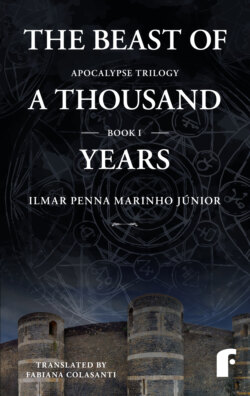

Читать книгу The beast of a thousand years - Ilmar Penna Marinho Junior - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

ON THE MONTH OF MAY, at 6 PM in Angers, the sun still touches the walls of thin layers of shale and limestone blocks of the imposing fortress. Its light shines and reflects on the seventeen towers and also on the helmets, shields, swords, spears, and crossbows of the Museum of Medieval Weapons. In the long eleven-thousand-square-feet gallery going through renovations, when the workers and the engineers left the site, at the lack of construction work and voices, in the silence of the nave of an empty church, the only thing left were the lights being tested for the approval of the new lighting system and the modern ventilation system that would be able to keep the environment controlled at a constant temperature of 68 degrees Fahrenheit.

Father Antoine Duvert was, as usual, late, this time by fifteen minutes. Curator Ferdinand de Sailly’s wrinkles looked more prominent on behalf of the inconvenience of his pudgy cleric friend’s tardiness. He arrived breathless, with his cheekbones on fire, ashamed for being late for such an important meeting. Ferdinand knew that the chubby, cheerful character liked to chat on the narrow streets, bistros, and flowery parks with no concern for his watch, already a few minutes forward to avoid the usual tardiness. Father Antoine Duvert had promised to himself to arrive in time for the honorable invitation to see the new forty-lux lighting before the official opening to the public. That would be a privilege for few, to attend a sneak preview of the reopening of the famous gallery. This was announced with a big fuss by the city, through billboards scattered throughout Touraine and ads on the internet — although the priest considered this “a tool of the devil” that corrupts men.

The priest immediately gave a huge smile to greet his friend, who waited for him on the castle’s drawbridge, frowning.

“Hurry up, I’m dying of curiosity. You know that God tends to forgive the careless and punish the grumpy” Antoine apologized jokingly.

The keeper of the castle, of the high nobility of Anjou, impeccable in his blazer and bowtie, went down the slippery stone stairway in hurried footsteps, followed by the sweaty priest.

“Be careful! Don’t stumble and fall down these medieval stairs! They are very steep, watch your step.”

“Oh, dear! These steps are still horrible,” complained father Antoine. “I almost fell, with your haste, like the world is coming to an end.”

They finally crossed the limestone portal, the boutique, the closed box office and, after going through the two doors, with a space between them to keep the acclimatization, they entered the long, lit hall of the gallery, which housed the tapestry.

Antoine took one step forward and stopped in front of the tableau of the first major character, sitting beneath a canopy, depicting St. John on the island of Patmos. He was in awe, silent, suspended in the contained admiring reverence before the embossed masterpiece woven by the magical hands of wonderful craftsmen. He shifted his eyes to the Seven Churches scene. He felt like he was walking on clouds with the new lighting. As if it was the first time he saw those biblical scenes of the canonical book and the four great characters, urging the viewer to be amazed by the contemplation and the allure of the exceptional masterpiece.

“Wow, it looks wonderful! It’s like the tableaus speak! This new lighting recovers the forgotten values of the Middle Ages. My eyes are thankful for being here” said Antoine, moved by the breathtaking longitudinal vision of the tapestry, completely restored and with its colors totally rejuvenated, that went on as far as the eyes could see on the large wall. The scenes came one after the other in six big tableaus, each one more dramatic and exceptional than the other. It became difficult for him to choose which one was more beautiful and illustrative, some abstract, others figurative.

“There have been several restorations on the seventy-seven scenes after the tapestry returned to the castle in 1906, because of the law of Separation Between Church and State. Although it remained linked to Catholicism’s worship, it was declared property of the State. It came back to Chateau D’Angers after a six-century absence. This time, for the gallery’s modernization, we’ve used cutting-edge technology” the administrator clarified while they slowly entered the perfect semidarkness of the room. This was guaranteed by the two-thousand diffusing lamps, powered by optical fibers, on the sequence of impressive images hung by thick Velcro strips, avoiding the use of nails that could damage the tapestry.

“You did it. The visitor feels blessed by God for being here, at the heart of Christendom and the renewal of faith.”

“We just have to tweak the placement of the tableaus.”

“It looks very good like this. Why mess with it? Leave it like that.”

“Look at this tableau of Christ and the sword, how the blues were enhanced,” said Ferdinand, slowly moving forward.

Antoine passed by the fifth scene, the one with St. John in tears, and thought of the miracle of the representation of the divine scenes, based on the saint’s apocalyptical visions. He squeezed his hands behind his body and stood before the sixth scene of the incredible vision of the world disfigured by the earthquake. He kept on walking in silence. He saw the grandiose scenes of the battlefields, of the terrible fight between good and evil, the land devastated by the seven plagues and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, the assault of the beasts sent by the devil, the beast from the Earth, the one from the sea, the frogs, the locusts. He contemplated the war of fire and the trembling of the earth. He took a few more steps and watched the fall of Babylon and, a little further on, with a hallowed eye, he saw the suspended New Jerusalem, triumphant, in the glory of eternal salvation.

“No one can imagine the work that has to be done to keep this masterpiece intact in the grandeur of its biblical dimension,” said Ferdinand, touched. “There’s been an immense effort in order to increasingly improve the state of preservation of this work of art so that the public could appreciate the prophetic vision of the Apocalypse and understand its message of hope.”

“These are paintings that explain the permanent struggle between humanity and evil. Look at this tableau, number 52,” said the priest. “It’s the scene of the Sleep of the Seven Righteous, who managed to resist the words of the Antichrist. They rest in their mortuary berths with their souls saved before ascending to the starry sky, taken by two angels.”

“Beautiful! The lighting canonized this image of the ascension to Heaven.”

“Look at this scene of New Jerusalem,” the curator pointed with his index finger. “It’s one of my favorites. It’s a shame we weren’t able to recover all the missing pieces of the tapestry. I’m heartbroken when I see, at the gallery’s exit, the frustration on the visitors’ expressions caused by the absence of the images of the Sixth Great Character, of the Horseman with the Horse the Color of Fire and War, of the Earthquake, of the Four Winds, of the Condemned Prostitute, of the Wedding of the Lamb, of God’s Verb, of the Birds Devouring the Ungodly and of the Final Judgment. I’ll never accept the fact that they’ve disappeared without trace. I won’t lose hope that one day they may find all the scenes and that they can come here, to complete the Revelation.”

“You didn’t mention the most important loss,” Antoine pointed out.

“Which one? I think I’ve mentioned all of them. Did I miss one?”

“You’ve skipped the scene of the Devil Caged for a Thousand Years.”

“You are right, Antoine. Forgive me. It’s so obvious I forgot! The visitors always leave frustrated because they haven’t seen the caged devil. Without a doubt, tableau 75 is the great absence in the gallery. Maybe the greatest one, because of its symbolism.”

“Do you have any idea of how the original scene looked?” asked the priest.

“Specialists have researched and came to the conclusion, based on the rigor of the color alternation throughout the tapestry, that the missing tableau 75 had a red background, since tableaus 74 and 76 have a blue background. And the devil was represented by a seven-headed dragon, the classic figure used as a representation of the Beast,” answered the curator.

“To the Catholics, it’s not the tableau itself that is important, but its message. The scene would show the insistence and the survival of faith. We imagine that, if the scene from the tapestry is traveling the world, with the devil on the loose, this explains so much crime, lust, perversion, and pornography, and the worst thing is that it may have worshipers all around the Earth…”

Father Antoine continued, as if preaching at the altar, and was totally taken by his pious, rapt inspiration before the curator’s admiring gaze, who saw him go from the state of artistic grace to that of divine grace.

“Then Satan would symbolically win the battle against faith if the scene is roaming free around the world, as he would also be. That’s why we, men of faith, preach to our believers to not use condoms, because sex is meant for procreation, never for pleasure and lust. They don’t understand that. The plague of AIDS is nothing but the victory of lust and degradation! They don’t want to hear us when we are against abortion and researches with stem cells from human beings who didn’t have the right to be born. They don’t understand that they are killing the embryos because life exists since conception, the soul is already present. They don’t understand why we are against human cloning, because only God can give and take life. They don’t want to hear God’s voice anymore in the Babylon of our time. Enough! I don’t want to talk any further. ”

“I’ve tried to recreate the lighting so that the visitors can find the hope of New Jerusalem again,” explained the curator, emphasizing his interest in the renovations.

“You definitely did it. Congratulations on the beautiful work of renewing the message of faith and hope in today’s frantic world. But this is not enough. We need to show the defeated devil. We have to lock up Satan for another thousand years.”

The curator didn’t immediately agree. He took the priest by the arm and led him to a spot where he’d left a blank space.

“Look at this, Antoine. Do you know why I left this space empty, between tableaus 74 and 76?”

The priest was silent. His eyes stared at the throne of God’s emerging river, which irrigates the hills of fruit trees.

“About six months ago there were news that the tableau with the caged devil had been seen,” confided the curator, whispering.

“Why did you wait until now to tell me this, you snake in the grass?”

“What good would it do to tell you if the Ministry of Culture wasn’t willing to finance its search, acquisition, and restoring? Now I can tell you because they have accepted to finance everything. I’m very hopeful. My intuition tells me that we’ll have the tableau back very soon. Our only problem is that we cannot have the police involved in the case as long as we are not sure about the authenticity of the tableau.”

“Where did this happy news come from? Can you tell me?”

“From Brazil,” answered the curator, raising his tone of voice.

“My God! From that far! You know, my nephew Aurélien was there during Carnival. He had his passport stolen.”

“Your sister’s son?”

“Yes. He liked it so much that he stayed for months. He told me he made good friends. He only came back because he didn’t want to lose his job at the Library of Historic Monuments in Paris. He graduated in Saint-Cyr, but decided not to become a gendarme.”

“Is he the researcher?”

“That’s the one. He’s a researcher and a police officer. Do you remember the case of the theft at the “Tiger’s” house in Paris? He was hired by the Clemenceau Museum and solved everything by himself. A fanatic had stolen the personal items and the manuscripts of the collection.”

“Of course, I remember it well. The case was in every newspaper.”

“He was here in October, spent hours visiting the halls in the Museum of Weapons. He praised the perfect state of conservation of the medieval crossbows. You know, he’s a crossbow champion, which is commonly known as bow and arrow, and has even won several medals as an archer in championships.”

“You gave me an idea. I’ll tell you later. Now I have to run home, or my wife will throw me in the lake of fire where the devil drowned. She has invited the mayor for dinner,” confided Ferdinand, nervous, walking quickly on the stone steps at the exit of the gallery toward the manor courtyard of the castle.

“Don’t tell me that coward is going to eat those delicious quenelles at your house?” teased father Antoine in the face of his exclusion from the gastronomic honor of the Rochemont de Sailly.

“We are very invested in the mayor’s reelection. He deserves it.”

“No, he doesn’t,” protested Antoine, looking at his watch. “My Goodness! It’s so late already… The boys must be worried about my delay. I’m late again.”

The curator made a sudden pause in his walk to ask the priest, still breathless as he climbed the stairs.

“Can you give me your nephew’s phone number in Paris?”

“Sure, I’ll send it to you by e-mail later,” the flustered priest said as goodbye.

Smoothing the folds of his bowtie, the curator took one last look at the twenty-four species of rose bushes planted in the garden facing the gallery’s outer wall. A refreshing wind hit his face when he crossed the castle’s draw bridge. In the silence, his lips smiled at the results achieved with the new lighting, which added to the biblical imagination a touch of the unimaginable, the halftone of the eternal temporality of the Apocalypse, as if the tapestry called for an exegesis, left hanging in the air. Or as if it wanted that the visitors always returned, as they return with tortured souls to the church masses or to the prayer before God’s altar so He can renew our certainty and the beauty of faith. Now the curator’s thoughts focused on the dream of bringing tableau 75 back to the gallery: nothing that a good sum of money couldn’t do — he laughed to himself.