Читать книгу It Might Get Loud - Ingrid Winterbach - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Plains of Huang-He

ОглавлениеSOMETHING, ONE DAY, starts closing in on Maria Volschenk. It manifests itself first of all in her body as a sensation of emptiness, exactly at the juncture of her last two floating ribs, approximately at the lowest point of the sternum, just to the right of the lowest point of the heart, more or less where the gullet enters the stomach between the tenth and eleventh dorsal vertebrae. Right there is what feels like an ice-cold, hollow spot – something closely akin to pain – gradually permeating the rest of her organs. The heart, the liver, the stomach, the gall bladder, the kidneys, the bladder, the intestine. Eventually the sensation of a percolating void, a vacuum, settles in her head as well.

All of a sudden everything seems pointless to her. Music she can no longer listen to. Nothing that used to give her pleasure does so any more. Neither lieder nor rock. Neither Charles Ives nor Stravinsky nor Mahler. Neither El Niño de Almaden, the Spanish flamenco singer (with his raw, discordant voice, his searing voice like acrid, fragrant moss). Nor the blind sheik Barrayn, making Sufi music from Upper Egypt, singing love songs and Koran psalms, deeply rooted in the ancient Bedouin tradition, accompanying himself on a little tambourine, held up close to his face, his fingers slapping, slipping, stroking its surface. Nor the family Lela de Permet from Albania, with the two toothless old men singing a duet in which one of them seems on the point of rending his shirt to expose the fragile, love-impaled heart. Nor Tallis, nor Monteverdi, nor Bach. Nor Berlioz’s settings of Baudelaire’s poems. Nor Schoenberg nor Alban Berg nor Britten nor Buxtehude.

She listens to her entire music collection, hoping that something in it can still appeal to her, but she feels an aversion to everything she listens to. An aversion such as she felt to certain odours when she was pregnant with Benjy.

Diminished, too, is her delight in the balminess and profusion of her tree-filled garden. She no longer inhales its fragrances with such sensual relish. The voluptuous excess of it rather disgusts her, truth to tell.

She thinks: How can everything have changed like that overnight? (It is at this time that she has the dream of her sister.)

Meticulously – because she’s a systematic woman, with a precise mind – she sifts through all the facets of her present and her past. Somewhere must lie hidden the key to this sudden beleaguered sensation in her body and her mind. She thinks of places where she’s lived, places she’s travelled to, people she’s known. She goes back as far as her memory allows. She compresses her memory, in an attempt to squeeze every last drop of information from it.

If she could, she would go back all the way to the womb, even to herself as an unfertilised egg in the body of her mother, but that is not possible. How far back must she go? To her parents, her grandparents?

Her father is seated on a big, loose boulder somewhere on a mountain with a woman, his first love. (Far beneath them a hazy landscape extends into infinity.) He’s wearing a tie and a white long-sleeved shirt. (Has he climbed the mountain in his shirt, tie and neat flannel trousers?)

Maria’s mother, not much older than four, is sitting on a tiny cane chair in front of her seated grandfather and grandmother. They were prosperous middle-class people. Maria’s grandmother (whose name she’s inherited) stands behind them. She is young, dressed in white like a girl. The expression on her face is unfathomable – the same expression she often has in photographs: aloof, reticent, wary of the camera. Is that where it started – in the undivulged, unrecorded disappointments and losses of her grandparents, her great-grandparents?

The same grandmother is standing, many years later, next to an elephant (with Indian trainer in knee boots and pith helmet: it must have been somewhere in Durban on holiday). She is no longer the same young woman, she’s dressed in something that looks like a dark, lightweight gabardine coat. Behind her is Maria’s smiling grandfather (an extrovert), his hand on his wife’s arm. Her grandmother’s arms dangle by her side, almost without volition; she is smiling faintly at the camera, but her gaze remains guarded and reserved, as if wanting to say: Don’t even try to unravel my secrets. (Is that where it started, this emptiness that feels like pain?)

Maria’s earliest childhood memories are sparse. An outside toilet (which she associates with one of her earliest dreams). Curtains billowing slightly, slightly in the wind. Red cement steps. The birth of her sister, Sofie. Her first day at school, the smell of Marmite sandwiches at break. The smell of poster paint (in powder form). The patterns they made with it on large sheets of paper. The way in which the sheets hardened as they dried, cracking where they were folded.

Was it this early school experience, does that perhaps provide a key? Perhaps one of many keys? School was not for the sensitive or the tender-hearted. Some of the children had an off-putting smell: of fish-paste sandwiches, of rancid butter, of pee. Mrs Roodt, her Grade Two teacher, one day yanked her own child from his desk and gave him an almighty thrashing, in full view of the startled class. Mrs Roodt had white-blonde, curly hair like a merino sheep. (Maria overheard her parents say that Mrs Roodt was much older than her husband.) She wore pearls and a shirtwaister with three-quarter sleeves, of which Maria can still recall the woolly texture. Her best friend, Dalena, once whispered to Maria that Mrs Roodt had big titties.

Is that where it started, in her first years at school – in the Grade One class of drab, depressive Miss Hendrikse, in the Grade Two class of Mrs Roodt with the merino hair and big titties? Early misery and misfortune, because school was a minefield of smells and unpredictable (often cruel and inconsistent) actions on the part of teachers as well as children.

She concludes that she feels neither longing nor nostalgia for any single place on the globe, nor for any single person – not even her deceased parents. The house in which she grew up feels to her like a place in which sorrowful, even violent, things happened. A house in which emotional damage was inflicted upon her, without the conscious intent or knowledge of her solicitous parents. The birth of her sister, Sofie, for instance. Impostor. For years she felt nothing for her sister. Only once she left home did she start finding Sofie’s singular take on things interesting.

Summer arrives, the rainy season commences for the umpteenth time. Everything ruffles its pelt and pinion, shell and carapace, in readiness for the season of brash unbridled burgeoning. Baby monkeys are born. They cling to their mothers who trapeze intrepidly from branch to branch high up in the trees. The monkeys gorge themselves on dates from the palm in front of her window; snap and eat the sweet young buds of the strelitzias. Maria dreams that she tries to garden in sandy soil; she sometimes cries in her sleep. Everywhere in gardens, in parks, there are trees and shrubs, big with gravid blossom clusters, the intensity of colour assails the eye. The flying ants are due any day now. They will launch their mating flights evening after evening in unstoppable swarms. Vulgar, Maria thinks, the profusion of this season, the fungiferous humidity and unquenchable fecundity. Only the loerie’s call remains modest.

She wonders if she needs an alternative vocabulary: Meek. Taciturn. Attentive. Forgiveness, purity, remorse.

Sometimes she wonders, in a preoccupied sort of way, whether little strings are indeed what tie the universe together, and if, with our awareness of three dimensions, we are perched as on the spout of a teapot in a universe of nine or more dimensions.

*

But Maria Volschenk is plucky and pragmatic. She has an enterprising spirit. She knows that she has to adopt some strategy to hold her own against the onslaught of the beleaguering void.

She devises a plan of action – quite apart from her regular contact with her two neighbours. (With the one woman she plays cards once a week, with the other chess once a week.)

The university offers evening classes and she attends a lecture series on the nude in pictorial art. The six instalments cover the Apollo figure, the Venus figure, the nude as embodiment of energy, of pathos, of ecstasy. In the last instalment an alternative convention is examined.

It is especially the instalments on the nude as embodiment of energy and ecstasy that interest her. These lectures examine the multiple transformations, variations and subtle and not-so-subtle deviations from and interpretations of the classical ideal. In the nude as embodiment of energy the body is directed by the will. The nude as embodiment of ecstasy renounces the will – the body is possessed by some irrational force. Satyrs, dryads and nereides represent, in the Greek imagination, the irrational element of human nature, the vestiges of the animal impulse that Olympian religion tried to sublimate or tame.

The yearning for levitation and escape is the essence of the ecstatic nude. Like all Dionysiac art, this figure is a celebration of the welling up of exuberant forces erupting as it were from the earth’s crust. From earliest times the ecstatic figure has been associated with resurrection: from its depiction on sarcophagi in ancient religions to the depiction of the saved souls in representations of the Last Judgement. A representation of the most ancient of religious instincts – the rebirth of plant and animal life after a deathlike hibernation.

In the last instalment of the series, the alternative convention, the body is pale, unprepossessing and defenceless, reminiscent of a tuber or a root. The bodies of the damned in the depictions of the Last Judgement, in Gothic paintings and miniatures, the Adam and Eve of Van Eyck, Van der Goes, Memlinc. Dürer’s women in a bath house, his four witches, Urs Graf’s woman stabbing herself in the chest with a dagger, Cranach’s sly Venuses.

It comes as no surprise to Maria that these tuber- and root-shaped damned and cunning nudes should interest her. She now feels no rapport with harmony and wholeness – the ecstatic and the deviant, that she can identify with much more closely at the moment.

*

The second lecture series that Maria Volschenk attends at the university deals with the art of the Bronze Age during the Shang dynasty in China (from the eighteenth to the eleventh century B.C.). (Maria reasons that the wider she casts her net, the better her chances of outwitting her vigilant self.) The first lecture provides a general introductory background. The origin of Chinese bronze casting remains obscure, but it’s generally accepted that pottery and bronze castings from the Shang dynasty are the oldest forms of Chinese art. The Shang empire was situated on the plains of Huang He – the Yellow River.

Her father told them – her and Sofie, her sister – about the Huang He and the Yangtze Kiang. He was a geography teacher but he should really have been a world traveller, visiting and discovering places. From as far back as she can remember, the names of places fascinated him, he recited them like mantras: the Yangtze Kiang and the Huang He in China, the Popocatépetl and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico, the Sverdrup Islands at the North Pole, Mont Forel in Greenland. He was enchanted by the places as well as by their resonant names. In that respect Sofie was his child – she was also seduced by the melodious names. Maria wanted to know where the places were on the map, their degrees of longitude and latitude, Sofie wanted their father to repeat the names again and again.

Maria casts the net as wide as possible, and meets up with her father again. Hello Dad. We meet again, on the plains of Huang He, the Yellow River, at the time of the Shang dynasty in China.

The subsequent lectures examine examples of the bronze artefacts. A gu drinking vessel, a three-legged jue container with dagger-shaped feet, decorated with a motif of stylised songbirds. A three-legged jia with pointed feet, a handle in the shape of a ram’s head. A you container with three-dimensional ram’s heads as support for the handle, decorated with dragon’s heads with serpent bodies. A zun container with rams on all four corners, serpents and inscriptions – technically so complex that it took twenty-one separate steps from the casting stage to completion. Another you container, wonderfully ingenious and highly ornate, in a combination of high as well as low relief, with a tiger-eats-man motif; the lid in the shape of a deer. A three-legged jia container with prominent, upright handles.

The last lecture surveys the use of ritual, and in particular its use of the so-called oracle bones. Tortoise shells and the scapulae of oxen were heated with branding irons so that the shell or bone cracked, and the resulting patterns used to predict the future. These divinations were the main activity in the household of the king, who had divine status. Before any important enterprise of which the outcome was uncertain – like a hunting expedition or a battle – the ancestral spirits were invoked and the interpreted prediction was then engraved on the shell or bone. The pictographic symbols used are of the earliest examples of systematised Chinese writing. The oracle was posed such questions as: ‘On the first day of Chia-chien of the first month we want to do battle against the Land of the Horses. Will Ti be on our side?’

The oracle bones vary from deep ochre to ivory, they are about fifteen centimetres high, and the simple inscriptions are delicately carved on them in vertical rows. On some of the bones the inscriptions have not been deciphered. The many varied household articles, with green patina on the bronze, are attractive, but it is primarily the delicate, impenetrable words of the oracle that appeal to Maria.

*

Maria and her neighbour Vera Schoonraad, with whom she plays chess once a week, watch a DVD series in which a number of Dutch psychiatrists talk about their subjects and themselves. In the various instalments they discuss, among other topics, the therapeutic process, emotions, childhood, the use of pills as against the talking cure, and depression. Maria hopes in this way to gain some insight into her own emotional condition. In one of the instalments the psychiatrists are asked what each of them regards as the most basic emotion. Shame, says one. Fear, says another.

The professor of biological psychiatry dons blue rubber gloves, produces a bucket in his laboratory, takes half a human brain from the formalin in it, and with a cotton bud points out the part of the brain responsible for emotion. The shape reminds Maria of a bisected coral that she once saw in an illustration. The colour reminds her of the pale white thorax of the large, bulbous spider that every evening for one whole winter lowered her body and spun her web before the bedroom window of Maria and her sculptor husband. The web and the body of the spider were covered in minuscule drops of water, and in the morning there was no trace left of either her or the web.

*

Karl Hofmeyr packs his bag, gets into his car and hits the road to his brother in Cape Town, who has been more or less of a headache to him for as long as he can remember.

At the garage opposite the Pavilion he buys a road map and plans his route. At the Wimpy in Estcourt the woman serving him touches her nostril. Without any ado Karl gets up from the table, pays, and leaves. His meal untouched. He washes his hands thoroughly, and when he gets to his car, he turns round, walks back to the bathroom, washes his hands thoroughly for a second time.

In Ladysmith he pulls up at a small shopping mall in the centre of town. He first washes his hands and then orders a sandwich in a small coffee shop that seems clean enough.

The Josias fellow phones him again. He doesn’t sound very friendly. He sounds impatient, distracted, as if he’s talking to someone else at the same time; voices can be heard in the background, and animal noises – the honking of a goose or something. (Godaloneknows where Ignatius is hanging out this time. Though the presence of a goose on a farm, albeit a farm against the slopes of Table Mountain, is probably not all that odd. )

‘Are you on your way?’ he asks.

‘I’m on my way,’ says Karl.

‘Good,’ says the man. ‘Before Ignatius can cause any further havoc.’

They’re cut off before Karl can enquire into the nature of the havoc. (Does he want to know? No, he does not want to know.)

He washes his hands. At the CNA he sees a book that interests him, but he gives it a miss. The shelf on which the magazines are displayed looks gungy.

There are a few things that Karl doesn’t do: he doesn’t do oil, he doesn’t do contact with anything that’s been handled by people who touch or pick their noses, he doesn’t do rats, excreta or open wounds; certain numbers spell disaster. But for the rest he’s really quite okay.

*

While filling up in Harrismith, Karl phones the Josias fellow. A young child answers. Where’s your father, where’s Josias? Karl asks. But only the child’s breathing is audible at the other end.

In Ladybrand he phones again. Josias Brandt does not answer his phone. (Here he and Juliana overnighted once on their way to Cape Town. They stayed in an A-frame house among pine trees. It was cold. The duvets in the place were made of a thin, synthetic material.)

In the café where they had supper that evening, Juliana told him about the autopsy she attended at school with some of her classmates. It was the first time that she’d seen a dead person, and the first time that she’d seen a naked man. They went there that day for a biology lesson, a small group of children, five boys and five girls. The body was kept in a room behind the police station. On going into the room, the first thing that struck her was the smell. It was not a smell that one could get rid of. It seeped into everything. (She made vigorous rubbing motions with her arms, as if trying to get rid of something sticky.) You couldn’t wash off the smell, she said. Not for days. It was concealed inside other smells. In the smell of cooked food. There was first the smell, then the body. The body was lying on a table in the centre of the room. It was covered. Not one of them said anything. When the cover was taken off (she made a plucking motion in the air), the naked body of a black man was exposed. Everybody’s eyes immediately focused on the sexual organ. Crinkly pubic hair and all, she said, with a slight laugh (half-embarrassed, half-apologetic).

The body had already been opened up. A long incision (Juliana demonstrated on her own body) from the top of the sternum to above the pubic bone. The skin and muscles of the chest cavity had been pulled apart to reveal the internal organs. The sound of blood and body fluids, Juliana said, was like when an animal is slaughtered. She had seen it as a child on the farm. A wet, squishy sound. It’s the same as raw liver, she said, raw liver is never dead; it always keeps quivering slightly. The internal organs were like that. The doctor removed the heart and showed it to them. (She opened up the palm of her hand to demonstrate how the man had held up the heart to their scrutiny.) He pointed out the arteries, the veins, the ventricles. They all nodded to show their interest, observed politely. He replaced the heart. Then the lungs were pointed out to them. They lay splayed open, like a butterfly. (She demonstrated the position of the lungs with her hands, bent at the wrists, the open palms angled towards her chest.) This was a good man, the doctor said, he didn’t smoke. The lungs were pink. But when the doctor removed a thin slice from one of the lungs, there were little black dots visible on it, like small, black roses. When you heat the point of a pin over a flame, Juliana said, and you prick a piece of paper with it, it leaves a small, round scorch mark. (She stabbed the table with her finger.) That’s what the spots on the lungs looked like. The doctor said it had been caused by pollution in the location. That was what you were exposed to when you lived in the location, he said. The intestines were pale. A blue-green colour. The doctor explained that it hadn’t been necessary to open up the man’s head. The injury was confined to his body. He had been run over by a tractor. His spleen and liver had been ruptured.

After that the dead man was sewn up, Juliana said. The skin and muscles of the breast cavity were drawn together again and he was stitched up. With a big needle, she said. (With two fingers she demonstrated how big.) The needle had a big eye, a rounded tip. (She pressed her finger on the table so hard that the tip flexed.) The doctor used thick thread and big stitches. The man was stitched up roughly with blanket stitch because (she hunched her shoulders apologetically) he was dead. The body was ready to be buried. There was no need for fancy stitching. Then it was over. She remembers that her mouth was very dry, Juliana said. We said goodbye to one another: See you at school tomorrow. Sheepishly. We couldn’t look each other in the eye. Three taboos violated in one go: we had seen a dead person, we had seen a naked, black man, we had seen it as girls and boys together.

What was the exact colour of the organs? Karl asked her. Pink, she replied. Pink, and looked around for a matching pink. By chance the colour of the chairs on which they were sitting. The organs were light against the man’s dark skin, she said.

*

In Smithfield he once again phones Josias Brandt. Again a child at the other end, with the gabbling of birds in the background. Geese or something. Once again the child doesn’t react, just breathes.

Karl has a pub lunch in the bar. The bar counter, when he places his order, seems reasonably clean. At the table next to him are four men. He can hear scraps of their conversation. As far as Karl can make out, they’re talking about people shot in an ambush. (He can’t remember reading about something like that in the paper recently.) It’s a fucking disgrace, says one (a big, solid man with shaggy sideburns). Just for that, says one of the others (with bushy, white moustache), just for fucking that. They were fucking cretins, says number three (with gold neck chain). I wouldn’t have let myself be caught like that. They should have known they could never pull it off that way. Were fucking not thinking straight from the start. Which still doesn’t mean it was okay, says Sideburns, not the hell. Shows you the savagery. Godalmighty, says Bushymouth, if I could climb in there, jesus, I would go ballistic mowing down that lot of pissheads. It was a ballsup, says Chainman, they should have moved in from the Bosfontein direction, around, they should have crossed the border further along, but then they went and fucked across at Witwater. Shit move, says Bushymouth. Shit. Old Nick was never one of the brightest. Not crafty enough. Crafty, that’s what you have to be. Crafty as a crocodile. I know him, he was my cousin. They all thought it was fun and games. (They order more beer.) We saw it all. On television, says Bushymouth. Fuck, says Sideburns, I couldn’t believe my eyes. That’s no way for a Christian to go. Fucking blood everywhere. Old Nick was shot in the chest. He didn’t die straightaway. As he was sliding down like that you know, half-slipping out of the car seat, his fucking hands in the air, they say he was still saying the Lord’s Prayer. But no, those people don’t understand Afrikaans do they, never mind the Bible. So-called police. Give him a gun, and he shoots anything that moves. Barbaric. No mercy. Pot him just like that while he’s praying. Blood everywhere. I’ll pot the lot of them in the trot, says Sideburns. (They laugh.) Blood everywhere, Bushymouth says again. The car’s a write-off. Merc 310 Diesel. Old Nakkie, reckon, bought it second-hand from the garage in Ventersdorp, so then he lent it to them for the occasion. Good condition it was in. Only seventy-six thousand on the clock. No, man, says Sideburns, it was also a blue Merc, but it wasn’t that one. So which one was it? asks Chainman. Which what? asks Sideburns. Which garage? asks Chainman. Man, that garage on the corner opposite the church. Oh yes, but that man went bankrupt, didn’t he? No man, that was the garage at the far end of town. Only seventy-six k’s on the clock. Yes, says Sideburns, but in any case, who wants to buy a car full of fucking bullet holes? And that blood smell you’ll never get out of the seats, you can have it valet serviced till you’re blue in the face, says Chainman. Fucking disgrace, says Bushymouth. Fucking disgrace, don’t think we’ve forgotten. We’re biding our time. Those buggers will never ever again get away with such a thing. Let one, let just fucking one put as much as the tip of a shoe over the border. Not that they wear shoes with their loincloths (Karl doesn’t hear very well). Laughter. They’re talking about something else. Karl can no longer hear very well, their heads together. He thinks they sometimes look in his direction.

And it’s not long before Bushymouth gets up and comes to his table. Ponderously he approaches, a big, overweight guy with a T-shirt that doesn’t look particularly clean, till he’s standing next to Karl.

‘Do we know each other, friend?’ asks the man.

He’s wearing a two-tone shirt, a copper bracelet, his moustache takes no prisoners, a mole on his right cheek and his hair was surely blow-dried with care this morning.

The man extends his hand. ‘Ollie,’ says the man, ‘Ollie of Steynsrus.’ Karl hesitates a moment before shaking Ollie’s hand.

*

Ollie was born in Kroonstad. His father worked for the municipality. After school he went to an agricultural college in Pretoria. It was his ambition to farm. His grandfather had a farm in the Heilbron district, between the Klip and Wilge Rivers. In the last few months Ollie has been feeling stitches in his prostate when he walks, but he can’t very well stand in one place all the time. He inherited part of his grandfather’s farm; the rest was lost to a land claim. His neighbours on an adjoining farm were recently murdered. Now his wife no longer wants to live on the farm. She says she doesn’t want to be scorched with an iron and strangled with an electric cord. That after being raped and dragged all over the house by her hair. No thank you, she says, then she’d rather die of misery in town. In the early morning he sometimes dreams of other women. Their skins gleam like copper in an unnatural light – the light of alien heavenly bodies threatening to destroy the earth. Sometimes he feels dizzy when he suddenly stands up straight. Sometimes it feels as if there’s a little hair at the back of his tongue all day and in his mouth there’s a sweet, metallic taste. Eating meat helps, and drinking beer. A cousin of his was one of the guys who were murdered that time in Bophuthatswana, when the AWB invaded the country just before the elections. In primary school Ollie was a Voortrekker. In high school he played in the cadet band. Three years ago he joined the Orde Boeremag, and rose quickly through the ranks. Now he is one of the executive officials, but what he’s really aiming for is one of the top positions.

*

‘What brings you here?’ asks Ollie of Steynsrus.

‘I’m on my way to Cape Town,’ says Karl.

‘You look familiar to me, friend,’ says the man, ‘I’ve come across you somewhere. Come and drink something with us,’ he says, gesturing towards the corner table, where his three pals are gazing at them expectantly.

‘Sorry,’ says Karl, ‘I’m in a hurry.’

‘Now I recognise you – you’re one of the chaps helping with the programme. You’re with subsection C, not so?!’ says Ollie.

Before Karl can reply in the negative, one of the others also comes up to his table (Sideburns).

‘This is one of the chaps from subsection C,’ Ollie says to him.

The other man also extends his hand. ‘Hercules of Senekal,’ he says, ‘pleased to meet you.’ He is big, his paunch precedes him, he has nose hairs and sideburns that would be the pride of any walrus. There’s a bit of food on his upper lip. It looks like egg, or chutney, it could also be bacon, or a bit of boerewors from the mixed grill. Or a piece of tomato, or toast, or onion, or a bit of kidney. Or liver. Minced liver fried with an onion. As children neither Karl not Iggy would put their mouths to liver. Hercules has a small mouth of which the upper lip has an unhealthy red tinge. His T-shirt reads ONS VIR JOU, we for you. To the left of the U there are three grease spots.

*

Hercules’s grandfather’s name was Hercules. He fought in the Anglo-Boer war and was seriously wounded at the battle of Senekalsdrift. His grandfather took him on his knee and told him about the war, and about the battle, and about all his comrades who fell in battle, and how they fell in battle, and about the pebbles and the blades of grass and the little footpaths and the sparse bushes and the low hills and the rock formations of the battlefield. Evidently it was all indelibly imprinted upon his grandfather’s memory. His grandfather said that the English were their arch-enemies and the blacks betrayed them. His father’s name was also Hercules. His eldest son’s name is Hercules. Hercules likes Karate Kallie’s videos. He likes Wild Life magazines. He likes liver and kidneys and tripe. Curry tripe. He likes meat potjie. He likes Kurt Darren. He has the hots for Patricia Lewis. He sometimes has filthy, filthy dreams. Sex with chickens and that kind of stuff. He likes large dams at sunset. The light on them is fucking awesome, especially when there are large trees on the opposite bank. Between three and four o’ clock in the afternoon is his worst time. Sometimes he thinks he’s going mad. He’s terrified that he’ll start hearing voices. The voices of women wanting to get filthy with him. He slips away from the office, he takes up position next to the wall behind the garage, and listens attentively. He can defecate only when he leans far back on the toilet; then sometimes he starts trembling inexplicably. His urine flows sluggishly. Sometimes at night his footsoles are sensitive and they itch, then he has to crawl to the toilet on his knees. Then he thinks: Now I’m an honest-to-God chicken-fucker.

*

Ollie brings his head up conspiratorially close, Karl edges back, on the man’s breath he smells beer and mixed grill. ‘Kleinfontein’s entrance is now also manned.’ He brings his head even closer. ‘You people are doing good work in the mobilisation section. Keep it up. Remember, our deliverance from uhuru will not depend on weapons and guns, but that doesn’t mean that we must not be fully deployed militarily.’

Behind Ollie of Steynsrus stands Hercules of Senekal. Rock-like. Is it Karl’s imagination, or is Hercules not quite as taken with him as Ollie? A bit mistrustful even.

A third chap, Chainman, has in the meantime got up and also come over to Karl’s table. (What’s going on here, is he being surrounded? What if they dragged him out of here and beat the shit out of him? Nobody would even know.)

‘Bertus of Holfontein,’ the man introduces himself. (Do these people have codenames or what?)

Bertus is likewise large of stature. Gold chain around the neck. (Isn’t that a bit ostentatious?) He’s wearing glasses with pink-tinted lenses (pink!) and the skin on his face has reddish blotches. His arms don’t look too great either – freckly and scabby. Skin must be exceptionally light-sensitive.

Behind Bertus stands a fourth chap. He’s the one who’s said least. He’s leaner than the others and his eyes in particular strike Karl – an unusual pale-green, and sorrowful, the saddest bloody eyes Karl has seen in a long time. The man extends his hand and says: Johan. The only one of the four who doesn’t have a crazy code name.

*

Johan’s father was a science teacher. He had something going with the PT teacher at school, she had bandy legs and blonde hair on her legs. His mother was always very merry, nothing bothered her, and then she had a stroke, must have been shock about his father and the PT teacher. After that she couldn’t talk or walk, his father had to care for her. She sat in a wheelchair, her puny legs were thin and hairy, she sometimes had a ribbon in her hair. Her pretty, tanned skin turned a pale yellowish-brown. So one Christmas she shot herself with the gun from the built-in cupboard in the guest room. He was twelve years old at the time. He always had a little fox terrier. He taught the dog tricks, like jumping through a hoop. The day his mother died, he knew that he would feel like an orphan for the rest of his life.

*

‘Can we buy you a beer?’ Hercules of Senekal nevertheless asks. (Menacingly?)

‘I’m on my way, thanks,’ says Karl, ‘my people are expecting me by early afternoon.’

‘See you at the national management meeting,’ says Ollie of Steynsrus.

Again he brings his head closer. ‘They mustn’t think we’re going to put up with being mown down. We have news for them. Or what am I saying?!’

The three men shake his hand before turning round and returning to their table. Ollie gives him a firm (encouraging?) slap on the back, but turns back halfway to the other table to say something else to Karl. He once again brings up his head conspiratorially to Karl’s and says: ‘You’re informed, aren’t you? You know that the time is approaching, don’t you? You know that the prophecies are going to be fulfilled in these days, don’t you? It’s more important than ever to be prepared, check your emergency provisions carefully, never stop praying for your country and your family. It’s not only Siener who predicted it all, it’s also Johanna Brandt. It’s Johanna Brandt in particular. We can all recognise the signs of the times; I’m just mentioning it. A man doesn’t want to feel later that he may have neglected his duty.’ He gives Karl another encouraging slap on the shoulder and before turning round performs some kind of salute that seems hideously suspect to Karl. Far from kosher.

Once more Ollie of Steynsrus turns round and says: ‘Your wife’s name wouldn’t be Suné by any chance, would it?’

But before Karl can reply, Hercules of Senekal gives Ollie of Steynsrus an almighty slap between the shoulder blades and says: ‘You’re thinking of Bertie of Henneman’s wife, you cunt!’ One of the others adds something inaudible, which the others laugh at raucously. Two of the others, not the Johan chap. (Party’s getting out of hand. He must get out of here.)

Karl abandons his half-eaten plate of food just like that; he can’t get into his car and drive away quickly enough. Before they discover their mistake and pot him on the trot as well. But not before he’s washed his hands thoroughly in the bathroom. Slap me with a wet fish, he thinks – uhuru. And what the hell did Johanna Brandt see? He’ll google her sometime.

When he walks past the four-by-four outside with OLLIE prominent on the number plate, a black dog inside the vehicle suddenly starts barking furiously. Karl half shits himself with fright. Why does the man have a black dog, shouldn’t he by rights have a white dog? A white wolfhound.

*

On his way to Colesberg he is phoned again, this time not by Josias Brandt, but by someone else. Where is he headed? asks the person, he has something for him from his brother. Should he believe the guy? How did the man find his number? Is he being watched? He’s headed for Colesberg, he says. Well, then he must travel via Bethulie, says the man, the parcel is there. When does he expect to be there? He can’t say with any certainty, Karl says cautiously. In that case he’ll just leave the parcel for him at the Total Garage on your right as you come in. In the Seven Eleven shop at the counter. (Eleven is not a good number, but fortunately the seven neutralises it.) Ask for Milos. What’s in the parcel? Karl asks cautiously. No, how the hell must he know, says the man. He was just asked to drop off the parcel. Who asked him? asks Karl. Man, says the man impatiently, he doesn’t know. Somebody. (Ignatius’s name hasn’t been mentioned once.) Somebody, okay? says the man and disconnects.

Karl considers ignoring the whole story, but there on his right as he enters Bethulie is the Total Garage and there is the Seven Eleven, and what the hell, let him collect the parcel and have done. Provided there is a parcel and it’s not some plot to bump him off.

Behind the counter is a woman wearing a cap at a jaunty angle. She’s chewing gum.

Karl asks to speak to Milos.

Without replying, the woman turns to the open door and shouts for Milos.

Milos appears from the back. He looks like the picture of King Francis I of France that Karl pasted into his history book in Standard Two.

Somebody left a parcel for him here, says Karl. His hands feel sweaty.

Milos in his turn says not a word, turns round, and reappears with a small parcel, wrapped in brown paper and tied with string.

Before touching it, Karl inspects it closely. His name is written on the parcel, and the handwriting is indeed Iggy’s. Unlikely to be a letter bomb.

He picks the package up warily by the string, because one corner looks rather greasy, and places it on the back seat of his car. He’ll open it later.

Before leaving, he buys a packet of small Jiffy sandwich bags from the Spar.

He decides to overnight in Colesberg. The hotels look like cheap joints (cockroaches and dirty baths; although nothing could ever beat the sulphur fumes of the bathroom in Bilbao). He checks into a guest house that looks acceptable enough. Diagonally across the street is an eating place and bar, explains the hostess. She looks like a game girl, but he is wary of this type – she looks like the kind of person who’ll turn out to have odd notions, such as that the fillings in her teeth are poisoning her whole body. Scrupulously he avoids her inquisitive gaze; she feels like chatting, he does not.

The place across the way fronts straight onto the street. There’s a small stoep with wooden railings in front and a few tables and chairs. Inside, the whole place glows like the interior of one of those lamps constructed from a big shell: both the dining room (where Karl eats a tough chop) and the smallish bar, and the little courtyard with its coloured lights. (Recollecting the scene later, he can’t remember whether he noticed the source of the pink glow – the red table cloths or perhaps the red walls in the dining room? The apricot-pink walls in the bar?)

After eating (so much for the celebrated Karoo mutton), he has a drink in the bar. Here there is a motley display. There are several mounted antelope heads as well as a warthog head on the wall, a baboon skull and a stuffed baby ostrich on a shelf, several draped flags (among which a Sharks flag – in the Karoo?), a Harley Davidson T-shirt against the wall, and many posters. The ceiling, floors and door are made of wood. A chandelier in the centre of the ceiling.

Outside, in the small courtyard, a group of men are sitting. One of the people in the bar informs him that they have just attended the heavy metal festival at the Gariep Dam (the former Hendrik Verwoerd Dam), the festival that Hendrik told him about. Karl is interested. He takes a seat outside, so that he can listen in on their conversation.

A big man has the floor. He’s clearly the main man. Slightly overweight, short, curly hair, somewhat sallow complexion and thick-lensed black-framed glasses. He’s wearing a cool T-shirt sporting a reproduction of the cover of Budgie’s Bandolier album. This meets with Karl’s approval. He puts him at more or less his own age – early forties. He is addressed as Stevie.

Two of the other guys he puts at more or less the same age – a man with a thin, cynical face, and another man whose hair sticks up straight on his head in a kind of long, trendy brush cut, a small mouth and a big chin (in profile his face seems decidedly concave). The other four chaps seem younger. They are arguing about metal bands and rock groups.

‘What about Wolfmother?’ asks one of the younger chaps.

‘No, man,’ says Stevie, ‘why would you listen to that kak? You should listen to Uriah Heep. They do it much better. They were doing in the seventies what these guys still can’t get right.’

‘What about DragonForce?’ asks another chap, ‘you must admit …’

‘What,’ Stevie asks menacingly, ‘what must I admit? It has no substance, it’s all fancy fretwork and macho spectacle.’

‘Yes, but …’ says the other man, ‘at least they know …’

‘They know fuckall,’ says Stevie. ‘They know fuckall, and the chances that they’ll ever know anything are fuckall. Save yourself the trouble of listening to them. Listen to Primal Fear – then you’ll hear what people sound like who know. Power metal extraordinaire, it wipes the others off the table, there’s no comparison!’

(Ralph Scheepers’s voice soaring like an eagle, thinks Karl.)

‘What about Rammstein?’ one of the young ones tries again, a chap with red hair and a big, round, open face.

‘So what exactly is it they play,’ demands Stevie, ‘is it metal or is it German industrial pop? Rather listen to Kiss if you’re looking for rock and roll with pyrotechnics. They were doing it way back in the seventies with much more panache and flair. Spectacle was their speciality, their theatre effects were sheer genius. And they were influential – Gene Simmons put Van Halen on the map. Or listen to Die Toten Hosen if you want to listen to a punk band. The real thing – real aggression.’

‘Killswitch Engage is amazing,’ says one of the chaps.

Stevie laughs disparagingly. ‘For Pete’s sake,’ he says, ‘that’s designer metal, man! In Flames is a much better band – much more authentic. Death Metal at its best. And if you want to go really heavy, listen to Machine Head – raw angst, raw pain, real!’

‘Nobody comes close to Yngwie Malmsteen, you can’t deny that, he’s a master,’ says the younger guy.

‘He’s a fucking Christmas tree! If you want to hear neat fretwork, or inventive shredding, listen to John Petrucci of Dream Theater. The man takes progressive metal to a new level. Malmsteen has been listening to too much Ritchie Blackmore. That’s not rock, man, that’s showing off. Guys like Petrucci and Robertson, they play rock! Those guys haven’t forgotten their blues origins. Malmsteen fancies himself as the avant-garde, but he’s forgotten where he came from. Ritchie Blackmore did it better long ago. Long ago. I repeat, if you want to hear genuine metal guitarists, listen to John Petrucci and Brian Robertson.’

‘Hasn’t the old metal age had its day?’ ventures one of the others, a tall, thin, nervous, dark-haired guy. ‘Shouldn’t they be making way for the new bands? Who’s still listening to Led Zeppelin or Judas Priest anyway? Aren’t Avenged Sevenfold and that class of band, My Dying Bride, Bullet for My Valentine, Trivium, the bands of the future?’

‘Come,’ says Stevie, ‘let me give you some advice. Drop this nonsense and go and listen to Thin Lizzy. Drop it all. Forget the lot. All those you’ve just mentioned. Purge yourself! Go back to the roots. Listen well to Brian Robertson and Scott Gorham of Thin Lizzy. Robertson turns the guitar into an extension of his body – it’s not superficial posturing, it’s gut-level creation and it rocks, it cuts to the bone. Blistering leads burning adrenaline for fuel. Guys like Robertson helped design rock – metal was just the natural next level. Drop those kids in their poser garb. Forget those skulls and wings and fake death-wish fantasies. Go and do your homework.’

The dark-haired guy leans forward with his head in his hands.

‘How can you compare something as powerful as Trivium with the old bands?’

‘Trivium were still in their nappies when Judas Priest and Motörhead were laying the foundations of modern heavy metal. There’s no comparison. These guys were the spearhead, the young upstarts are just the rabble in their wake – teenage angst, no more than that. Judas Priest and Motörhead did the groundwork. They stormed the castle. They were the battering ram. Guys like Trivium can’t top that. And they know it.’

One by one the young ones take on Stevie, or try to take him on, but he’s like a great, irritable bear, just lowering his head and growling menacingly to keep the snapping dogs at bay. The man with the cynical face says nothing all the while, just chortles covertly after every one of Stevie’s salvos. And the other fellow, the one with the chin and the quiff, his attention is elsewhere. (If Karl had to guess, it’s with his sorrows. Extensive sorrows, by the looks of it.)

‘Armored Saint,’ says Karl (when he can’t contain himself any longer), ‘they’re great. The best.’

Stevie turns on him sharply.

‘Were you at the metal festival in Benoni?’ he asks.

‘No,’ says Karl.

‘At the Aardskok metal festival in Roodepoort?’

‘No,’ says Karl. ‘I was at the Graspop Metal Meeting in Belgium.’

‘Great concert,’ says Stevie.

‘Michael Schenker Group,’ says Karl.

‘Waited for years to see Schenker live,’ says Stevie, ‘and then there nearly was a fuckup with the sound system.’

‘He almost walked off-stage in a rage,’ says Karl. ‘He’s one of the reasons why I attended the festival, and then his show was a great let-down.’

‘Yep, agreed,’ says Stevie, ‘but amazing that Saxon played.’

‘Old Biff Bayford still jumps about onstage like a salamander on a frying pan,’ says Karl, ‘even though his hair is as white as snow.’

‘Amazing energy,’ says Stevie. ‘Did you check out Arch Enemy in one of the tents?’

‘They were great,’ says Karl. ‘Awesome. Angela Gossow is beautiful – she growls like a tiger when she sings. Beauty and the beast all in one.’

‘Whitesnake,’ says Stevie.

‘I went to see Whitesnake just for Reb Beach,’ says Karl.

‘Lord of the strings, as David Coverdale calls him,’ says Stevie.

‘Do you remember what Lemmy of Motörhead said,’ says Karl, “We’re Motörhead. Don’t forget us. We play rock and roll.”’

‘Rock and roll,’ says Stevie and chuckles. His whole body shakes.

‘Oh, man,’ says Karl, also laughing.

Stevie leans across to him, shakes his hand, and in his eye Karl recognises the unquenchable glint of the true initiate.

But when he returns from the toilet (with the same deep-pink glow as the rest of the place), somebody in the bar grips his arm firmly. Firmly as in firmly. With this firm grip the man steers him all the way up to the bar counter, making sure that he remains close to Karl at all times. Much too close, but manoeuvring space is in short supply, because the room is small and as it is he’s pressed up virtually against one of the other clients. (Where do all these customers crawl out of at this time of night in a Karoo town?)

The man has shoulder-length hair and dark glasses. (Like Jeff Bridges in The Big Lebowski. He and Juliana watched it with huge enjoyment. More than once.) And where is Karl headed? the importunate fellow demands. To the Cape, says Karl (trying to get away, make a duck). A family visit, perhaps? asks the man. Business, computer business, says Karl. Is he sure it’s not perhaps a family visit? What’s he having? asks the man. Nothing, thanks, he was just on his way out. And again he tries to slip away, give the guy the slip, get out of his vital sphere.

Wait, says the man. Places a gentle, but firm, hand on Karl’s arm. Just a moment, he says. Karl looks down at the hand on his arm. It’s not a hand, it’s closer to a deformed talon – its colour is a deep, deep, no-holds-barred – shocking – purple-red, a colour he wouldn’t normally associate with human skin. Instinctively he glances at the other hand too, now resting lightly on the counter. Same colour.

Skiing accident, says the man, following Karl’s gaze. Almost didn’t survive. Frostbite in both hands. The age of miracles hasn’t passed, has it? I think I know who you are, says the man. Karl says nothing. The brother of Ignatius Hofmeyr? (Oh no, Karl thinks, oh no.) Am I right? Karl considers for a moment saying it’s not him, he’s never heard the name Ignatius. The man takes off his dark glasses. Now he looks even more like Jeff Bridges. Pale eyes. It looks as if they’ve been exposed to too much snow glare; the irises have a weird, flat glitter, as if the Big Bang is reflected in them. Karl nods lightly, affirmative. In that case, says the man, we have an urgent matter to discuss. Shall we have something to drink first? Karl’s mouth is dry. A beer, thanks. Ignatius is in trouble, says the man, he’s in serious trouble. Call me Joachim, he says, and extends one purple talon to Karl. Karl hesitates before shaking the man’s hand. It is cold, with a squamous texture, like the hide of a leguan.

Over the man’s shoulder Karl sees them still arguing outside, he think he hears Stevie saying kak, kak, it’s all kak they’re listening to, forget it all, start from scratch, before the Joachim guy closes in with still greater persistence, wholly claiming Karl’s attention and totally obstructing his field of vision with his obdurate presence.

‘You have been sent to me tonight,’ says Joachim, ‘because I have an important message for you.’ (What does the man mean – who sent him?’) ‘Your brother Ignatius and I are friends. I don’t know if you’re aware of it, but Ignatius is in mortal peril. I happen to know that you’re on your way to him. That’s good. You must make him understand that he must get in touch with me urgently before it’s too late. I may be able to help him. If anybody can still help him, it’s me. I have the necessary knowledge. You may well understand nothing of all this now, but believe me when I say that Iggy has ventured into dangerous territory. Take my word for it. He’s walking a tightrope. There are powers battling for possession of his soul. It’s not a foregone conclusion that he’ll survive psychically. The adversaries are strong. They are cunning and demonic. Look at my hands,’ says the man, and holds out his two hands to Karl as if for closer inspection. Karl stares, he’s never beheld anything like it – two beetroot talons.

‘I got off lightly,’ says the man. ‘I suffered damage only to my body. On the face of it a skiing accident. But much more than that. Call it a close encounter. Call it a confrontation with a hostile power, call it evil, call it what you will. Call it a power dormant in all of creation – a hard, bitter rind enclosing the sweet fruit of truth. I was lucky to escape with my life. Damage to the body – that’s the least. Iggy may not be so lucky. He is very close to the abyss. Once he’s in it, nobody can reach him. Do you want another beer, or perhaps something stronger?’

‘Something stronger, thanks,’ says Karl. His mouth is exceptionally dry, even after the beer.

‘You do realise the gravity of the situation, don’t you?’ asks the man. Karl nods. ‘You understand that Iggy’s soul, his being, is imperilled, that he’s moving on the brink of a bottomless abyss?’

Karl nods. He rubs the thumb and index finger of his right hand gently and unremittingly against each other; he has an overwhelming urge to wash this hand, with which he’s shaken Joachim’s hand.

‘I am afraid that Iggy may already be moving in the Sitra Achra, the other side, the realm of the demons, the Sheddim. He’s already had too long an intimate conjunction with it. He has focused for too long on these things – bridges have been built, intimate conjunctions established. This imperils his life, as I’ve said.’

Karl gulps. ‘How do you know this?’ he asks.

Joachim regards him for a moment in surprise.

‘I know it,’ he says, ‘because I’m an initiate. Iggy and I have been walking the same road for a long time. It’s because Iggy possesses knowledge that his situation is so perilous.’

‘Knowledge of what?’ asks Karl. Though soft, his voice sounds shrill to his ears.

‘Knowledge of the world,’ says Joachim, ‘and of the worlds behind the observable world – the material or physical dimension of reality, the lowest of the four spiritual worlds.’

Karl nods. A wrong number has suddenly popped up in his head. He has to get away from here. Quickly. Before something bad happens.

‘I’ll do that,’ he says, ‘I’ll definitely convey your message to Iggy. Thank you.’ And before the chap can get in another word, Karl turns round and makes his way nimbly and fleet-footedly through the other customers in the bar, but the man is equally nimble and fleet-footed, because before Karl has reached the front door, Joachim has clutched his arm again with one of the beetroot talons, forcing Karl to turn round and face him.

‘You think I’m talking rot, don’t you, you think I’m a freak and a charlatan,’ says the man (for sure, thinks Karl), his face close to Karl’s, his crazy, white-pale Big Bang eyes keeping Karl’s gaze captive.

‘More dedicated, more sincere people than Ignatius have perished before now,’ he says.

‘What is it that you people are engaged in?’ Karl asks.

Joachim is silent for a few moments. Just fixes Karl with his stare. ‘The true nature of things,’ he says, ‘the truth behind the illusion.’ He’s silent again. ‘That’s what Ignatius should be engaged in,’ he says, ‘but at the moment he’s engaged in a struggle for the survival of his soul. And believe me,’ says the man, ‘that’s no mean struggle.’

At that moment Stevie and the two men who were with him, the two chaps who said nothing all the while, come in from outside, from the courtyard. As Stevie walks by Karl, on his way out, he flashes him the V-sign and says: ‘We’re Motörhead. Don’t forget us. We play rock and roll.’ Karl laughs, flashes the V-sign back, and over Joachim’s shoulder wistfully follows the little group with his eyes as they go out by the front door and turn right.

‘Here’s my number,’ says Joachim. He gives Karl a card, lets go of his arm and disappears again in the direction of the bar.

*

Iggy’s parcel is still lying unopened in his room. Not just yet, he thinks. He struggles to drop off to sleep. At three o’ clock he gets out of bed. He slips the Jiffy bags onto his hands and opens the parcel. He deftly chucks the brown paper wrapping into the dustbin.

Inside the package is a pile of A4 sheets, neatly folded in half, typed. (He remembers the holiday when Iggy taught himself to type.) On a separate sheet, in Iggy’s spidery scrawl – in case Karl still had any doubts that it really came from him – is written: To my brother, Karl Hofmeyr, this account of the months of my drawn-out agony. Read and reflect, but be assured, the time of my salvation is at hand.

He starts reading the document and wishes it was less legible.

In these days, Iggy writes, the plot against me is coming to fruition. A certain person is set on conquering my soul and if possible, on murdering it. I shall not mention the person’s name, but in due course it should become clear who it is.

After these opening sentences Karl can read no further. He thinks: Later. Not now. Where does the frostbite fellow fit into the picture, would Josias Brandt have anything to do with Iggy’s condition, and what does Iggy mean by the time of his salvation being at hand?

*

A few years ago Iggy had a paranoid incident. It lasted for a few months. He recovered.

When they were small, Iggy always had a saucer in his room containing a germinating bean in moist cotton wool. Always. He checked every morning to see how much the bean had grown during the night.

Iggy slept with his glasses on the cabinet next to his bed. Karl watched him closely. Perhaps he was waiting for Iggy to wake up and play with him.

Iggy made things. He was always busy. He made a volcano out of papier mâché. He fashioned things out of clay – ghosts in grottos with skulls and bats. Adroitly he folded the wings of thirty plasticine bats and suspended them upside-down in the clay cavern. Not one of the bats was bigger than one centimetre.

Iggy drew strong men, animals, birds, various breeds of dog, cars, whales, dolphins, dinosaurs.

Iggy did not like loud noises or sharp light, he was exceptionally sensitive to both.

Iggy was not into music, not like him, Karl.

*

From Colesberg Karl makes an early start for Beaufort West.

What was the last, the very last DVD he and Juliana saw together? Was it Werner Herzog’s documentary on Kuwait shortly after the Gulf War, Lessons of Darkness?

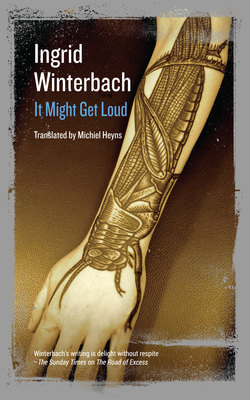

That evening he’d rather have watched It Might Get Loud once more. (That moment when Jimmy Page, with his long grey locks, takes the guitar and plays the first few bars of ‘Whole Lotta Love’, and Jack White and The Edge both give a tiny grin of recognition and pleasure.)

But Juliana prefers classical music (something else on which they don’t see eye-to-eye).

A hellish landscape. Vast surfaces of oil kilometre upon kilometre like dams of water; in which the air is reflected as if in fact in dams of water. And then the burning oil wells – pillars of fire ascending into the sky, and massive, billowing clouds of smoke. Herzog’s quotation from Revelations – the opening of the fifth seal – made the hairs on Karl’s arms stand on end. At one point two female voices interweave as the camera moves high above the devastated landscape. From the corner of his eye he saw tears trickling down Juliana’s cheeks. Do you recognise the music? he asked her. Arvo Pärt’s Stabat Mater, she said. Perhaps she was crying for the music, perhaps for the relationship, which so evidently was drawing to a close.

*

Just this side of Hanover, after he’s been on the road for about an hour, Karl suddenly wonders whether he did after all pack Iggy’s letters. He draws up at the very first garage in Hanover. Oh good fuck, he’s left the letters on the table in the guest house. Oh Christ. He knows it for certain and with a sinking heart. To make doubly sure he rifles through all his stuff. But he can see it lying there, on the table. At a café he asks for a telephone directory. Fortunately he remembers the name of the place. No, says the woman, the maid has tidied up there already, she saw nothing. He gives the woman his cell phone number. Please phone me if the parcel turns up somewhere. Will do, promises the woman.

Iggy’s letters are gone. He’s gone and lost Iggy’s letters. Iggy took the trouble to write to him and he’s lost them before he’s even read them. That as fucking well. If he’d read the letters he might have had a better idea of what’s up with Iggy.

He’s sitting at a table in a café, his head in his hands.

His cell phone rings. It’s Josias Brandt. Damn him.

‘When are you coming? You have to get a move on.’

‘I’m close to Beaufort West,’ says Karl (not quite true), ‘I’m coming as quickly as I can.’ He feels like telling the man to just fuck off. Just fuck off and leave me in peace.

‘Shouldn’t Ignatius perhaps see someone in the meantime, a doctor or someone?’ he asks.

‘A doctor,’ says Josias, ‘if a doctor were to see him now, he’d have him locked up in an institution at once. His condition is in any case no longer my responsibility, as I have said repeatedly. He has to get out of here before he burns the place down, as he’s threatening to do. He attacked one of the geese with a stick.’

Excuse me, this is Iggy we’re talking about here. Iggy used to cry when he or anybody else stepped on an insect by accident.

‘Couldn’t I perhaps talk to him on your cell phone?’

‘Are you also out of your mind!?’ says the man. ‘Do you think I want my phone smashed to smithereens? Nobody dare go near him today.’

‘Is he eating?’ Karl asks.

‘I don’t know if he’s eating. I can’t take that on as well.’

When he wants to get going, there’s clearly something wrong. The car won’t start.

Holy fuck, that fucking-well as well.

Now the car has to be seen to, in this godforsaken town. Why do these small towns depress him so, what’s wrong with him? Why on earth did they chop off the tops of the cypresses, didn’t they have anything better to do here?