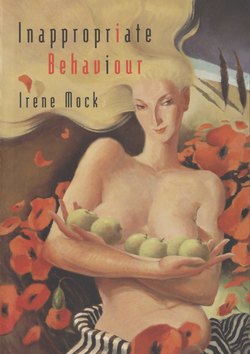

Читать книгу Inappropriate Behaviour - Irene Mock - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

What We Have

ОглавлениеOur beginnings are utterly mysterious—why are we born? Why when and as we are?

ON NIGHTS WHEN SHE COULDN'T SLEEP Julie would go into the room meant for the baby. She would look at the bassinet, the tiny clothes, the stuffed animals. Then she would come back to bed.

"Michael?" She touched his shoulder. "Michael, I keep thinking about the baby."

He struggled to wake up, put an arm around her. "Jules—honey, you know these things happen."

Yes, she thought, but there's got to be a reason. The two glasses of wine on Michael's birthday. Or maybe the week she was sick with flu in her first trimester? Or perhaps something larger. Some lack of faith?

"Michael," she said. "Promise me you won't tell anyone what's wrong with the baby."

She touched his hair but he frowned and pushed her hand away. "You know, it's not easy for me either."

She shuddered, drawing her hand over her swollen belly. Inside my body, my husband and I have created an abomination. In primitive times such a baby wouldn't be allowed to live. Probably the mother, she thought, wouldn't be allowed to live either. Maybe her mate would have killed her. Even twins—normal twins—were put to death because only animals had litters, so the mother must have mated with an animal. Did Michael know what they'd created? Did he have any idea?

"Michael," she said, "will you promise me please?"

It hadn't moved for several days, maybe longer. But the baby had never moved much anyway. She didn't want to bother Michael so she distracted herself, painting the baby's room, going to all the fitness and pre-natal classes. Still, when her father had greeted her over the phone with his proud, "Hello, Mother!" she had to protest. "Dad, please don't say that. I'm not a mother yet."

Why didn't she tell Michael then that she felt something was wrong with the baby? She knew all the things that could go wrong. It had annoyed her when friends said how well it was growing. When some would pat her belly and laugh. And wasn't it just like the doctor, when he couldn't find the heartbeat—three days ago at her regular eighth month check-up—to jiggle her belly, to say jokingly to the baby, "Wake up!" Finally, though, he'd given up, sent her for an ultrasound . . . .

The baby had been her idea. When they were talking about having it in their second year together, Michael was uncertain. Once she became pregnant, he began buying her vitamin supplements, talking about the trips the three of them would take, starting a special bank account for the baby. He built a little table and chair set for her thirty-fourth birthday.

Put the baby things away, people told them. Put them away. There'll be another time.

But whenever she went out Julie noticed how cautiously they approached, their trapped look as they avoided her big belly.

"You'll try again. Won't you?" they'd say.

SHE COLLECTED THE CLOTHES in a bag. Bending over, annoyed at her big belly, she helped Michael dismantle the crib. They put away the stroller, the Snugli, the bassinet. She felt him keep his distance, afraid, even accidentally, to touch.

Just as they were finishing, Bob and Andrea stopped by. She and Andrea had gone through their pregnancies together discussing everything from her Cheerios and ice cream, Julie's pickled herring and cheese, to birth positions ("On my side," Andrea joked, "like a voluptuous Rubenesque painting.")

Once she'd asked how Andrea felt about bringing a child into today's world and she said, "Not hopeful. But even five or six years with a child would be better than nothing."

Not long ago, at a party, she'd overheard a man say, "You know when a war's going to break out because right before it happens everyone gets pregnant. Something to do with survival of the species. . . ."

She looked at Andrea's big belly now, then down at her own. "Is there anything more you need for the baby?" she asked. "Please. Go upstairs and see."

When Andrea came back, her hands hung empty at her side. "We still need a bassinet, but … are you sure?"

The bassinet. It was one of those silly things—white, with pink and blue cats. Julie had found it at a garage sale. She and Michael had sung as they brought the bassinet into the living room, falling exhausted on the couch. Andrea had complimented them on their good fortune. "I've gone to all the garage sales and haven't come across one bassinet yet. You must be lucky."

"My, what ridiculous looking cats!" Andrea laughed nervously now, as Michael helped Bob carry the bassinet downstairs. "It's bad enough you can't get anything for a baby that isn't pink or blue. But cats with both colours?"

Julie waved as Bob and Andrea pulled away. When they were gone, Michael turned to her and they held each other in the driveway. "I love your hair, Jules," he whispered, stroking the fine red strands that fell to her shoulders.

A WEEK PASSED. It had been four weeks since the doctor last heard the heartbeat. He was concerned. "If another week goes by you could risk spontaneous haemorrhages which can be fatal, but," he tried, seeking to reassure them, "there's still only a small chance of this occurring."

She nodded. How calm, professional he was. She could feel her eyes glaze over. "What would you recommend?"

The doctor appeared thoughtful. "You could have it out right away, of course."

A C-section. Michael agreed. "They're quite common, honey. Lots of women have them."

She nodded again, but she felt cheated. "Actually, I'd prefer not to." Couldn't she have anything?

The doctor looked down. "Well dear, it could be difficult. Without a head . . . ."

"Without a head?" Why say that? She glanced at Michael, then back at the doctor.

"What I mean is, since the head's not fully developed .... Since it may not dilate the cervix. . . ." The doctor shrugged to indicate how useless it was to explain. "Well Julie, you're a nurse, I'm sure you understand."

"Why not get a C-section?" Michael argued. "Surely you don't need to carry it any longer."

"It. Why does everyone make it seem as if I'm walking around with a rotten vegetable," she said, "a turnip or cabbage."

He put his arm around her. "Don't you just want to get the baby out and be done with this?"

No. She did not. Though just why she couldn't explain. She took Michael's hand from her shoulder and pressed it between her own hands which were cold, shaking. Inside my body, my husband and I created a baby with no head. No brain, she thought. Not human. But the baby didn't feel that way to her. This baby was her dream. Even a dream that died, you didn't stop carrying.

She would not have the baby taken from her.

TO DISGUISE HER PREGNANCY, she wrapped herself in Michael's huge raincoat. She didn't want strangers cooing over her now. She didn't want anyone patting her belly. Above all, she didn't want to have the baby where everybody knew her; where all the nurses she worked with would offer their sympathy, and see the child. She and Michael had decided on Vancouver. It was well over five hundred miles away but they had friends there—or could, if they wanted, remain anonymous. Maybe she wouldn't need the C-section; a specialist could induce labour. In case she had any problems with the airline, the doctor had given her a note: May travel by air, thirty-four weeks pregnant, not in labour.

This was not entirely true. She was over thirty-six weeks, actually, and women are not supposed to fly in their last month of pregnancy. She'd started having irregular contractions the night before. But that morning when the doctor examined her and referred her to a specialist she had been reassured it would be safe to fly.

Now she was afraid she might have the baby on the plane. She didn't want anyone to see it. She wasn't sure if even she and Michael would want to.

Before they'd decided to go to Vancouver, she'd told the doctor they planned to look at the baby.

He advised against it. "You never know how you or your husband will react. And then it will be too late to wish you hadn't."

"But I'm a nurse," she'd said. "I've seen babies like this."

"An anencephalic?" He looked at her as if she were crazy. "Usually these babies are miscarried early because the brain is absent or so poorly developed. But," he shrugged, "I'm sure you already know that."

He could have said anencephalic monster, that's what the medical books called it. She read in one text, A sizeable number of cases have been suspected to be environmental: a maternal fever in early pregnancy, pesticides and herbicides, recent potato blights in the United Kingdom. There was a small photograph in a book by a lay-midwife who wrote, These babies have, for some reason, disproportionately long arms and legs. But the baby, who had lived a week, wore a scarf around its head.

"I can always decide at the time, can't I?" she'd told the doctor.

He shrugged. "The decision's yours. But if it were up to me—if you were my daughter—I certainly wouldn't want you to."

She stared at him.

"You know, you might be risking your marriage."

"My marriage?" She looked at Michael and laughed.

"It may affect how you make love. Sometimes it can produce such guilt . . . ."

She sucked in her breath.

"This kind of baby is worse than anything you've seen. Not even nurses like these babies," he said.

HALF PAST MIDNIGHT. The delivery room was dark except for a small lamp in the corner. Julie's doctor—the new one, a specialist—stood bent over the baby and talked to the nurse. Julie couldn't hear what he was saying but when he approached the bed he told her, "I always encourage my patients to see the baby. I think it helps."

Now she and Michael were alone in the delivery room with the baby and nurse.

"Does the baby look human?" Julie asked.

The nurse said, "Yes."

"Are you sure?"

"Yes. Let me show him to you."

There was nothing left to do now but to look. The nurse brought the baby close. She had wrapped him carefully, so that the back of the head was covered by the blanket. The baby had no forehead. He didn't look like a baby at all. "Please," Julie said, "take it away." But just as the nurse turned to go, Julie whispered, "No, please, wait."

"I see an old person," Michael said. Julie cried and looked away.

She reached out and touched the baby's feet. Cold, very cold, but the toes were perfect. Each had a tiny nail, and the skin at the joints was wrinkled.

Then the hands.

Cold, but again, perfectly formed.

Michael took the baby in his arms and held it out to her.

"No," she said, "I can't. I can't."

He turned away with the baby but the nurse said, "Are you sure?"

Michael cradled him in one hand while the other stroked his small feet. "Julie . . ." he said quietly, holding the child toward her.

THE NEXT MORNING the doctor told her she could go. It was over. Leaving the hospital, Michael took her hand and they walked the few short blocks to Queen Elizabeth Park. The sun was hot, the sky clear, and the world suddenly full of people.

"Remember when we first heard the baby's heartbeat in the doctor's office?" he asked.

She looked at him. Yes.

"And that time on the patio, when I put my hand on your belly and just at that moment he kicked?"

They stood at a rock wall looking out over the gardens. Below, amidst a profusion of colours, people walked, couples posed in front of flower beds. Young people, old people, men in tuxedos, women in bright wedding gowns.