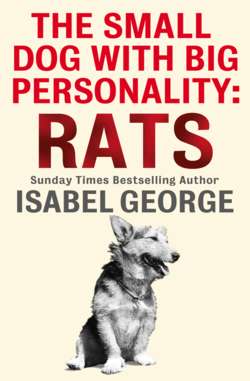

Читать книгу The Small Dog With A Big Personality: Rats - Isabel George, Isabel George - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter 2 Rats – Delta 777

January 1979: a crisp winter morning and a four-man ‘brick’ patrol was on duty in the town of Crossmaglen, South Armagh. Plumes of cold breath rose into the cool air as the tread of heavy, black boots cracked the silence on the streets. Brick Commander, Sergeant Kevin Kinton of 2 Company, 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards, was leading the way. A small, scruffy, rust-brown dog jogged at his heels.

Experience had taught Kinton to be wary of parked cars and he ordered his men to take to the middle of the road, not the roadside, to avoid a purple car parked at the kerbside. Better to take the risk of being picked off by a sniper than accept the virtual certainty of being blown to pieces by a car bomb. They were coming to the end of their patrol and were now close to the heavily guarded gates to the British Army base when another patrol approached. They were, in Army terminology, ‘working the pavements’: two soldiers taking each side of the road. The little dog left Kinton’s heels. Maybe he decided to say hello to the soldiers in the other brick. Maybe he saw a friend from the base or just preferred to go into town with the others rather than return to barracks with Kinton. Whatever his reason the bristly mongrel wagged his fox-like tail as if to say ‘see you later chaps’, and trotted away. As Kinton and his men entered the huge barbed-wire topped gates, their grey frosted morning flashed orange. Time stood still. One soldier took the full blast and ran, engulfed in flames. A cloud of black ash and burning debris fell as the others fought to smother the fire covering their friend’s body. It was most likely a radio-controlled petrol bomb placed in the boot of the purple car. The IRA would sometimes mix explosives with petrol to create the effect of a firebomb. By adding a ball of soap-powder flakes the explosion would force a spray of flaming soap mixture into the air. It would stick to and scorch anything and anyone it touched.

Fire and ash filled the sky. The sound of soldiers shouting orders mingled with the rumble of an armoured car and the distant thud of a helicopter. Soldiers attended to their injured friend, his clothes blackened and smouldering. The purple car was a raging ball of flames covering a dark metal skeleton. As the cold air smothered the heat and the smoke began to clear, Kinton caught sight of another casualty. Singed and smelling of burnt fur, the little brown dog had limped his way back to the main gates of the camp. His coat spattered in the soapy mixture released in the explosion, the dog was badly burnt and half his tail was missing.

Once more the dog had endured the same horrors as his soldier friends. His desire to run with the men on duty had earned him their respect. Over and over he proved that he was not afraid. That day, the soldiers nearly lost a comrade and their faithful little mascot dog lost half his tail. But it was not the beginning or the end of this dog’s relationship with the British soldiers. It was one more chapter in the story of a remarkable dog called Rats, Army number Delta 777, the ‘soldier dog’ of Northern Ireland.

Mystery surrounds the real date that Rats joined the British Army. The sectarian ‘Troubles’ (as history has labelled them) in Northern Ireland attracted the presence of the British Army from 1969 onwards. Regiments arrived and then left four or five months later, each soldier spending their tour of duty constantly on the front line defending the territory and protecting the people who came under Sovereign rule. For the soldiers who served in Northern Ireland it was, in their words, the worst kind of guerrilla warfare, fought against a politically feverish terrorist group, the IRA, fuelled by Protestant and Catholic differences. During the height of the unrest in the 1970s the province was a part of the United Kingdom where even hardened soldiers knew they were wise to feel fear when they walked the streets. It was not a safe place for a soldier or a dog.

Rats grew up in Crossmaglen. On the surface, this small Ulster town was nothing more than a collection of houses, a church, a primary and a secondary school and 13 public houses, serving a population of just over a thousand people. Lying on the River Fane, this seemingly tranquil place boasted a castle, a heritage of fine lace making and a typically large market square where local farmers brought produce and where the townsfolk met to trade and talk. The place was no stranger to the bustle and chatter of an active community but the memorials in the square were testament to a darker facet of this community’s identity. A memorial ‘to those who have suffered for Irish freedom’ stood a stone’s throw away from a statue erected in memory of a British paratrooper killed by an IRA bomb. Blood ran on the streets of Crossmaglen and bullet holes peppered its walls and walkways. Republican and Catholic, the town was a strange dichotomy: it was both peaceful Irish community and a war zone.

It was the location of Crossmaglen that controlled and maintained the air of simmering hostility and the reason why its inhabitants kept a self-protecting silence. Crossmaglen was a frontier town. It lay just one and a half miles from the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland to the south, across which the terrorists slipped at will. No one knew if it was safe to speak to anyone, so they chose caution and said nothing at all. The natural warmth of the Irish had to be stalled as anyone showing any friendly behaviour towards the soldiers could risk reprisals.

Of course talking to a dog was quite different and it was here, in an environment of fear and hostility, that Rats came into contact with British soldiers for the first time. Like them he often patrolled the Ardross estate on the outskirts of Crossmaglen. It was his territory and where he ate and slept, although there was nothing visible to eat or to sleep on. The grim grey houses looked in on each other as if they were ganging up on anyone who dared step too close. Certainly the soldiers experienced a palpable sense of intimidation from each net-curtained window. There was rare comfort to be found there for a stray dog either, although Rats never gave up hope and never deviated from his daily routine: first an early morning tour of the houses, paying particular attention to the odd one or two where he had found or scrounged a scrap in the past.

Tour complete he headed for the wasteland that stretched like a no-man’s land beyond the houses. Nothing more than a bare patch of earth this place had once known grass and maybe there had even been a playground for the children, but neglect and the persistent Irish rain had reduced it to part scrubland and quagmire. Tethered piebald horses left to fend for themselves dragged their dry lips over the ground in the hope that they could conjure up a blade of grass to eat. And stray dogs snapped at their hooves for sport. Rats set himself apart from the pack. He was always his own dog and that’s one reason why he endeared himself to the soldiers.

He could have attached himself to any of the British soldiers that served in Crossmaglen, and maybe he did in part, but the history of this mascot dog started to be plotted in 1978 thanks to 42 Commando Royal Marines. The regiment, assigned its six-month tour of duty in Armagh, decided to tolerate the playful antics of this persistent little dog and it all began with bootlaces. Rats loved them and the men admired this playful rust-coloured puppy-like animal for stepping forward and fearlessly lunging at the soldiers’ big black boots and making a grab for the long laces. The locals may have wondered why such a small dog didn’t fear a kick from those boots but he didn’t. It was fun and fun was a big part of Rats’s personality. Anyone asked to give their first impressions of Rats would say ‘scruffy’! Then dirty, flea-ridden, revolting, determined, cheeky, charming, happy, intelligent and loyal to his friends. He was all of that and so much more besides. Corgi-like in looks and stature, Rats stood about eighteen inches off the ground on four sturdy legs. His body was as bristly as a broom head and his fox-like face was topped off by a pair of fox-like ears. And where he wasn’t coloured copper and brown on the top he was (after a bath) a dazzling white on his chest and underbelly. What 42 Commando saw when they first met Rats was the muddy, scruffy version, and not a puppy at all but a dog that had already seen six or seven years of life in the bomb-scarred border town. This dog had been born into the Troubles.

To find such a happy little dog in such a dismal place was a pleasant surprise to the soldiers, who had soon became accustomed to being largely ignored by the human residents of the town. The game of tugging bootlaces with this playful stray became a regular feature of the patrol of Ardross. After a short while the soldiers even looked for the cheeky brown mongrel. They told their comrades to look out for him too. They didn’t need to feed him; he was happy to have their attention and he gave them a cheerful respite from their isolated duties. But it was Rats who decided that he was going to stay with his new friends and one day he simply followed them ‘home’.

Home, to the outside world, did not have many fireside comforts. The high steel fences, rolls of barbed wire and concrete towers of the British Army base in County Armagh looked forbidding by day and night. The site took in the old police station, which was clad with sheets of corrugated iron and hidden behind thick walls of barbed wire to protect the helipad. Offices, accommodation and the cookhouse shared the confines of the narrow building which just about had room for a small brown dog. His first bed was a blanket on the floor of the briefing room. His second bed was any vacant or warm and occupied bunk he could squeeze into.

It didn’t take long for Rats to settle in and soon he was a constant member of the Army’s daily patrols. He had an unusual waddle rather than a walk but it didn’t hamper his speed in following the soldiers. His loyalty to his soldier friends was instant and he was quick to learn that he could be useful to the troops. When he was out on manoeuvres Rats would sense the approach of strangers and warned the soldiers with a soft growl. His canine sense of hearing being so much more acute than a human’s, the advance warning saved lives in an ambush situation. Soon Rats’s reputation as a lucky mascot spread and he was in demand by almost all brick commanders. Some saw a dog as a liability rather than an asset to a patrol, but one good experience with the dog was enough to convince them of Rats’s loyalty.

Regiments came and went in Crossmaglen. Faces changed with the arrival and departure of the ever-present helicopters that flew from dawn to dusk between six locations. Company commanders came over from the mainland four or five days ahead of their men. They had probably spent three or four months familiarizing themselves with the terrain and the problems they would face on arrival. Section commanders would be in position a week before the start of their tour and finally the men of the three platoons that would form each company on duty arrived on site. The airlifting and dropping of the men was well rehearsed for security and accuracy: the helicopter dropped eight men in and lifted eight men out and repeated this until the operation was complete. As the men of 42 Commando Royal Marines departed in October 1978 they handed over to 2 Company, 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards, and brick commander Sergeant Kevin Kinton was one of two non-commissioned officers (NCOs) in the advance party. He was heading in for his first tour of Northern Ireland.