Читать книгу Four Legs Move My Soul - Isabell Werth - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 RHEINBERG

ОглавлениеThose who look a good horse in the eye do not need any explanations. A horse is a horse is a horse. The beauty of the horse lies in him being a horse. He looks at us, attentively and calmly, and we see ourselves anew in his dark gaze. We smell his lovely aroma—tangy grass and grain, the cozy warmth of the barn, the sweetness of apples and carrots. And what else? Wanderlust? A longing for closeness? With a satisfied crunch, the horse bites into a carrot while holding our gaze.

The horse allows us to touch his nostrils—so soft, comparable to the skin of a baby. His nose wrinkles when he collects a piece of apple from our hand. He breathes out with a snort.

When the horse slowly moves forward in the field, step by step, eating grass constantly and carefully, he radiates peace. He gives us a sense of quiet presence. When he canters up a hill, he transforms into a cloud of speed and oxygen.

Horses can captivate us, never to let go again.

With hardly any other living being can a human connect as closely over so many years as a rider can with her horse.

The rider takes care of the horse, grooms and brushes him, allows him to rub his nose on her shoulder. She mounts the horse, enfolding him with her legs, sometimes for hours. She follows the fascinating mechanics of the horse’s movements with her body—rocked, swayed, tossed, and caught again. The rider does not move her horse, but is moved by her horse. The horse is willing to carry her.

But why are horses so interested in us? Why are most of them motivated by the desire to please us humans? To do right by us? Why do so many of them have the need to be led by us? It is a gift they give us, and one for which they have paid a high price over the course of the centuries. Still, they stand by us persistently.

The connection of the rider with the horse is always mutual, physical, sensual. And, ideally, two souls from different worlds correspond in one time and place that only they call their own.

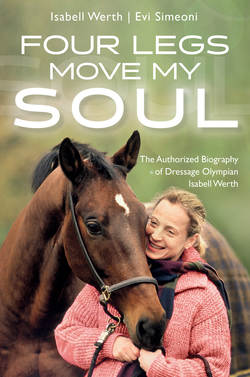

Gold-medal-winning Olympic dressage star Isabell Werth’s passion for horses does not start with ambition. She is living a long love story. It is, however, part of this love story that she asks a lot of her horses, that she works them intensely. For her, as an athlete and entrepreneur, discipline and self-criticism are self-evident. The many tears she has cried on all possible winner’s podiums during her unparalleled career show exactly this when the performance pressure finally eases off. Euphoric happiness hardly ever waits for her up there on the podium. Up there, she feels pride, gratification, reassurance, satisfaction…and relief. When she does experience perfect moments of happiness, it happens quietly, at home, without an audience, when she is just with her horses in the here and now.

Imagine winter is over, spring is close, and everything is starting to turn green and bloom. You are outside with your horse, you are riding, and you are thinking that it could not possibly be any more beautiful than that very moment. For me, that is utter happiness on a horse—to feel completely independent of competition, to feel only that the horse is with me and I am with the horse. That is bliss.

Those who visit the horses at Isabell’s facility in Rheinberg, Germany, can look forward to ample scratches, pats, and friendly interactions. The herd is all lined up, ears pricked, next to one another in a neat and tidy barn, the superstars of the dressage world: Weihegold, the black beauty. Bella Rose, the Kate Moss of horses. The once unpredictable Satchmo, long since retired and increasingly turning into a “horse-Buddha.” Emilio, the shooting star. Belantis, Isabell’s great hope for the future, who stands in his stall like a Pegasus in the mist. They all turn a friendly face to their visitor, sniff you, and start to communicate in their individual ways. Obviously, they are just as sociable as the boss herself.

Even Don Johnson, called “Johnny,” the cocky hooligan, has a look so gentle and attentive, you would almost believe he was up to no mischief. A closer look in his stall, with its strange safety devices and rubber toys, reveals all: when this horse is overcome by the urge to play, he shreds everything around him to pieces, such as his automatic waterer, regardless of whether he hurts himself in the process. In doing so, Johnny has missed several important competitions—the 2016 Olympic Games among them. There is no piece in his stall that has not had to be replaced. Don Johnson has even managed to kick in a mirror in the indoor arena. Isabell nonchalantly waves this observation aside—yes, he is just a naughty boy. He also likes to buck every once in a while when she is in the saddle, and he has come close to throwing her in the dirt. Of course, she defends herself and puts him in his place: “Johnny, stop this nonsense!” Maybe he knows that, truth be told, Isabell enjoys being his sparring partner from time to time. Later, with a soft smile on her face, she will offer excuses: “He was only offended, as I have not given him enough attention lately.”

Isabell has dedicated herself to horses with her head and heart, body and soul. She is a person who radiates a sense of security and peace of mind, a solid groundedness, a steadfast stability. Nothing about her is aimed at trying to make an impression—for her, what counts is what happens. Her nerves seem to be made of steel, she looks out at the world with a confident glance, and she makes absolutely clear that nothing and no one can scare her. And yet, her horses, these large, sensitive animals, throw her into periods of deep doubt, time and again, and sometimes even into despair.

The public hardly knows this side of Isabell. She can be beaming and funny during interviews or at parties and receptions—and sometimes she laughs so heartily that people turn around. This is the cheerful side of her, a characteristic originating in her native Rhineland, rather than the sensitive soul that is hidden from view most of the time. When we see her competing at horse shows or on television, we see her lips pursed in concentration, we see her frowning out of sheer willpower, we see her tongue pushed below her lip, into her chin, and we can tell that every fiber of her body is geared toward maximum performance. This was the way it was when Isabell first picked up the reins at the highest level of dressage sport, and it has not changed three decades and many medals later. It sometimes even seems as if the doses of the “competition drug” she needs to consume regularly have gotten bigger and more frequent. She hungers for that adrenaline, even when it requires a sort of game of cat and mouse: If Isabell has to face the victory of a fellow competitor in a particular class, her opponent better not be so foolish as to think her luck might continue. The Isabell Empire will strike back the next day, shattering her opponent’s resistance, all the more painfully. It will seem as if she prepared the carpet and immediately pulled it out from under the other rider. This is how she recharges. This is her very personal warfare.

Isabell Werth, competition monster?

Of course, such results require a horse of superior quality and training to help her control the field, and yet, it is still never guaranteed, not even when the rider is Isabell Werth. She has gone through hard times over and over, periods when success eluded her because of a lack of top-level horses, and where, for a while, only tenacity kept her in the game. Nevertheless, in the later stages of her career, Isabell succeeded bringing several aces to the game. It is not a coincidence that she managed to sit in several top positions in the world rankings at the same time. She became the most successful rider in history following her performance at the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro in 2016: She has won six Olympic gold medals in twenty-four years, nine World Championship titles, and twenty European Championship titles. What is most astonishing about this is the plurality: While even the most formative figures of her sport generally ride to top-class international success with only one horse, two at the most, Isabell has qualified a total of eight horses for championships, including Olympic Games, World Equestrian Games, and European Championships. She has brought approximately thirty horses to the highest levels of the sport—a monumental achievement to which no other rider has even come close. This is most likely why, after years of fighting for respect and justifying her success, her role is slowly beginning to change: Isabell is becoming more and more a respected “Grande Dame” of dressage, one who no longer has to prove anything. Sometimes, now having advanced beyond the stages of competition that house envy and resentment, she experiences the third stage of her career—one where, during its best moments, the battle, the competition, and the proven experience are no longer at the forefront. Instead, it seems as though stars rain down on her, as during her win at the World Cup Final in Omaha in 2017. There, all of a sudden, everything seemed to be easy. She beamed on the podium and sprayed celebratory champagne instead of crying painful tears. A new Isabell! She turned the ceremony into a joyful party.

It’s moments like these where I stop and think sometimes: Have I arrived? Have I come full circle? All those challenges still waiting for me, all the young horses that I still want to bring on, my business and my family—these take up my thoughts in such a way that there is no time for sentimentalities. Most of the time, I collapse into bed exhausted at night, knowing that the next day will be just as precisely timed and organized, whether at a show, in our own arena, or at promotional events. But one thing is clear: Best of all, I like to fall asleep at home, at our farm in Rheinberg, surrounded by my family.

The podium, on horseback, in the dressage arena—this is where Isabell has belonged since the day she was born on July 21, 1969. It was the same day the first person set foot on the moon. Isabell, however, has remained grounded. She needs the place where she grew up; it mirrors her whole life, her personality, and her dreams. It is where she longs to be when she is racing along a highway somewhere. And it is, where she recharges the energy she needs for a constant and tightly regimented daily routine.

When Isabell was a child, the remoteness of her home sometimes bothered her. She had to be driven everywhere, the riding club included. Today, she is happy about the idyll it provides and feels tremendously privileged to have been raised in such comfort. There might not have been any vacations together with her parents—someone always had to stay home to take care of the animals at the farm—but when she was home, her parents where always there and always available for her, not just when she had problems.

The Werth family is down-to-earth. They’ve been farmers for generations and still live on the farm at the Winterswicker Field in Rheinberg on the Lower Rhine like happy islanders, offering each other protection and safety. Family is everything. Four generations lived at the farm at the best of times. Her grandmother, who was one hundred and two, only showed serious signs of weakness and age in her last two years. Her parents, Heinrich and Brigitte, two lively but not very tall people, give the farm every ounce of who they are. Isabell is the “boss” nowadays, with her partner Wolfgang Urban and son Frederik, and her sister Claudia (older by three years) with her family. That Isabell is now the one making the decisions does not bother her father Heinrich—a cheerful man with plenty of natural “Rhineland wit.” On the contrary.

“She is the king in our family clan,” he says proudly during tea time at Isabell’s long dining table.

When Isabell was a child, he tilled over fifty acres of land almost alone. Mother Brigitte ran the household, which was considerable. (Father Heinrich’s parents lived in the house for twenty-seven years.) Isabell’s father produced barley, oats, corn, and beets in the fields. In addition, there was livestock: dairy cows to manage, pigs to breed and rear, chickens complete with a rooster, geese, ducks, rabbits, dogs, and cats.

“All animals were created by the good Lord,” says Heinrich Werth.

For a while, he even bred nutria and pigeons. And, of course, horses, which today are not bred for work, but rather for pleasure only.

Isabell’s father operated a classic “mixed” farm, which were once common in their area, remaining unchanged for centuries, but which are almost extinct today. Today, all the farms on the Winterswicker Field are shut down, the buildings have been converted into houses, and the families have leased their land to large agricultural businesses. The “old way of life” is dying. Now, everything is about quantity and large spaces, fertilizers are used intensively, and the land is worked with large machinery—small farms just aren’t profitable. Heinrich Werth belongs to the last generation of farmers that operated in the traditional way. He is a farmer, through and through, but his life was even harder than that of his ancestors. Unlike his parents’ generation, he could not afford employees. Brigitte Werth also had to go about her tasks differently from her mother and mother-in-law—both had employed a maid for all their lives. The farm no longer yielded that kind of profit. Even using a “swarm” of children as a means of free labour was no longer a solution, as compared to the times where families with twelve or more members were not uncommon, they had few offspring.

As a child, Heinrich Werth witnessed the days when horses were still used to plow the fields. Through all of his work life, he had to carry heavy loads, day in, day out, since the mechanization was not as advanced as it is today. Thus, the arrival of the combine meant a great relief, although Heinrich Werth still worked industriously on his farm, got up at the crack of dawn to feed and to milk, sat on his tractor for days, and was, eventually, exhausted. He reports that he felt way worse at fifty than at eighty. His back refused to function, his discs, his sciatic nerve—he had to use a wheelchair temporarily. But he never complained. Happiness is what is most important to him, he says.

And a family who sticks together.

My sister and I grew up among all these animals. We loved and cuddled the piglets and the calves, and it was our chore to take care of the bunnies. We could count on a new “fur baby” every day, and we ran over, petted them, and thought they were cute. Of course, we knew that these animals were going to be butchered and, eventually, eaten. But that is how it was; we lived off what the farm produced. We also had no problem providing the obligatory pig eye for our biology teacher’s class on dissection in school. (Our classmates were horrified and started to scream!) As soon as a piglet weighed over a hundred pounds, “its time had come.” Whenever a pig was slaughtered, we girls looked forward to the vet’s attendance, as he examined the meat for trichinae. He let us look through the microscope. Making sausages was a natural next step for us and certainly nothing repulsive—quite exciting, actually, and quite yummy! A piece of the fresh meat was roasted or cooked that night and everyone looked forward to it and enjoyed it.

Isabell’s father knew every single cow and pig and took responsibility for their well-being. It was a life both with and off the farm animals. Even if they were slaughtered one day, the children learned to never lose respect for them. They were close to the animals physically and not repulsed. If the livestock were sick, they were treated, and nobody rested until they were well again. The family looked after the animals and cared for them three hundred and sixty-five days a year. Nevertheless: They were still livestock and not toys.

As a child, you are completely impartial; you don’t think about it. The horse is there; the dog is there. And you don’t develop an inherent kind of fear, but the animal is part of your daily life, almost part of the family. You go into the barn in the morning, the animals are fed; it is a rhythm, it is simply responsibility, and that is how you grow up.

Isabell knew everything. For example, when the sows had their piglets, they were allowed to romp about in the field. There was also a boar. One aggressive fellow put the fear of God into Isabell one day.

My dad had bought a new boar. Usually, a boar had his tusks sawn off right away as they can be razor-sharp, but this one hadn’t had this done. There was a cow field next door, and this boar apparently had never seen cows in his life. He went completely crazy, and cut open three cows, one so badly she could only go to the butcher. Attempts were made to stitch the others back together. To experience something like that, to see firsthand how fast something can turn on you and become dangerous—I found that deeply impressive.

Growing up closely with different animals, Isabell developed a natural relationship with them, one that was elemental and instinctual. The animals got involved with her, and she expressed interest in them, opened up to them, formed relationships with them, which cannot be described with words. Rural children approach animals without immediately expecting something from them. They do it simply because the animal exists. It is impossible for a city child to obtain such genuine access. The city child cannot imagine what it is like to grow up so closely together with an animal and to enter into a mutual interdependency.

The affection for all animals that started in her early chilhood is the key to Isabell’s joy in her life with horses—and also to her success. Over the years, she has further developed this special understanding, has refined it, enriched it with new experiences. And she has made it more professional. Anthropomorphized, is what she calls the instrumentalization of a skill she acquired as effortlessly as other children learn Spanish, French, or Portuguese from a nanny. Isabell was able to open up not only one country with the language that came to her, but an entire universe. The animals seem to speak to Isabell, and she seems to be able to hear them.

“A gift,” her father says. “We did not teach her it.”

“We have been asked where she got it from,” says her mother. “It was the Lord who gave her so much feeling.”

Isabell’s skill to anticipate is legendary. She knows what a horse is about to do, even when an outsider cannot perceive any signs whatsoever. Thus, she is able to take preventive measures, to guide reactions into sensible directions, or to prevent worse outcomes. She can latch onto a horse’s sense, understand his individual behavior, and find ways to interpret it.

I can feel it somewhere in a fiber of my body. In a nerve that was unknown to me before. In my hands, my seat, in my side, somewhere in the body. Somehow, the horse shortly freezes, he appears a tiny little bit nervous, reacts a tad differently than usual. I can’t explain it, but the feeling is there. Just a small perception sometimes, an instinctive hesitation, a gut feeling, which is confirmed later. Then I say to myself: Look at you, you were right, and I integrate this aspect into my experience. It is a form of communication and instinct. Instinct plays a large role. It has become very refined over time and has developed through the many different horses I have ridden. From my little fat pony to the Grand Prix competitor.

Gigolo, my first gold-medal mount, was a generous teacher with regard to communication. He offered himself to me and brought an extremely honest willingness to perform. I listened to him and learned to manage his overboard ambition. He managed to focus on me and the competition situation and always played along. As a Grand Prix debutant, I took this for granted. But the reliable heart of this horse was a great gift for me at that stage of my career.

Gigolo made it possible for Isabell to withstand Anky van Grunsven’s competitive onslaught for years. Anky was her biggest rival from the Netherlands, with whom she “fought” some nail-biting duels in the international ring.

Later, Satchmo would wreak havoc on everything that Gigolo had taught Isabell. Satchmo was also a very forward-oriented horse, but with such a moment of surprise! Isabell listened carefully, sharpened her perception, used her brain, and turned her nervous system on “high”—but he remained unpredictable, even for her.

Nobody has challenged and sharpened my sense of perception as much as Satchmo has; he was my second great teacher after Gigolo.

The more sensitive a horse is, the more difficult he is. A horse that has an “ordinary” disposition causes few problems for his rider; however, this type of horse is not ideal for the kinds of requests Isabell is likely to make in the international dressage arena. This horse will be able to learn movements, but he will not be able to “play his part” in the performance in the kind of way that is needed for success on this stage. He will not know when it’s all or nothing; he will not fight with all he has left in the decisive moment. He will not unfold magically in a way that touches the audience. He lacks that “something special.” And this horse would demand too little in return from Isabell Werth.

Isabell loves and, in fact, needs those horses that, amongst riders, are referred to as “hot.” She tends to load up on a kind of mental electricity, to work herself into a state of fervor that matches the horse. The hotter her horses, the more impressive their performances together—it is almost to the point where everything falls apart, where Isabell can no longer reach them, and where they lapse into complete hysteria due to pure overeagerness. This is the major challenge for a world-class dressage rider. She must work along this fine line. Every competitive outing is a borderline experience, where the genius of the horse threatens to turn into insanity at any moment. There, on the brink, is where the competitor who is Isabell Werth feels most comfortable. These moments do not leave her paralyzed with fear. She savors them like an acrobat does when waiting to drop from the very top of the circus tent. She draws her own energy from them.

Besides, Isabell does not see her goal as reaching the top as smoothly as possible. Every step needs to have something special. The way she gets there is even more important than getting there: Her pursuit is the art of bringing the most different, and sometimes difficult, of horses beyond their weaknesses to optimal performance.

Isabell’s parents are constantly amazed by their daughter.

“She will look at a day-old foal,” her father Heinrich says, “and will pretty much tell you where his career path will take him.”

As a farmer, he finds this ability especially impressive.

Or consider the story of Amaretto: The poor horse was technically the next “Crown Prince,” the one to follow in Gigolo’s footsteps, but he was not healthy. Frequent colics tortured the gelding so often that, finally, he had to be taken to live at a veterinary clinic. Whenever she was not on the road competing, Isabell visited him whenever she could, observing her horse in his medical stall for hours, standing next to him and trying to figure out how she could possibly help him. After some time, she took Professor Bernhard Huskamp, the head of the clinic, aside and said: “Whenever Amaretto pulls up his lips and curls them, that is when the next colic episode is about to announce itself.” The veterinarian ignored her at first, then began to wonder, and finally took a chair himself and sat down in Amaretto’s stall for a few hours. He discovered that Isabell was right. Whenever Amaretto pulled up his lips in a certain kind of way, another colic was about to begin and the horse would lie down soon after.

Her father, the experienced farmer, just said, “You simply cannot learn something like that.”

Isabell is deeply concerned whenever horses in her care become ill. After all, one virus can threaten her entire stable. Early in 2018 a mysterious infection spread through Isabell’s barn only days after a glorious show performance. The feverish illness manifested itself dramatically—in fact, she lost two horses. The fight against the virus brought Isabell and her entire team to rock bottom—they had no strength left. More than a hundred horses had to be checked several times a day for weeks on end—not only her own, but also precious boarding horses for which she had taken responsibility. It seemed the vet was a permanent guest at the barn—when he was not on site, he was constantly on the phone. At one point, several thermometers actually stopped working due to overwork and had to be replaced.

It was so cold outside the barn that canisters full of disinfectant were frozen. Double-door systems with disinfection mats were put in place to try to eliminate transfer of the virus. Luckily, Isabell’s current competition horses had stalls in a separate barn aisle and were given medication to strengthen their immune systems, so they were not affected by the wave of infection. But the entire Team Werth had to fight a downright battle for weeks.

Isabell, the tough one, the woman who accepts any athletic challenge almost with pleasure, was more anxious than she’d ever felt before—she was faced with an uncertain situation and a certain powerlessness. Only days before the outbreak she had told the press that, during her career, she had never been so happy and relaxed than in her current streak of athletic achievements. But only a day later the old wisdom was confirmed: Problems always arise when you least expect them. This can apply to many things but is even more true when you are dealing with vulnerable living beings. It is in those moments that your entire life’s experience still will not help you.

The Werth family has always interacted with horses. Heinrich fox hunted. Isabell’s mother, Brigitte, the daughter of vegetable and fruit farmers close to the city of Bonn, brought a mare called Palette with her when she married Heinrich. Brigitte rode Palette leisurely on hacks and had some fun with her at the local riding club.

Isabell, somewhat disrespectfully, calls this “housewife riding.”

Isabell started riding so early that she can hardly remember her first pony, Illa. She first sat on Illa at five years old. Her first ride was on “a little black horse”—this is all she remembers. Then it was the mare Sabrina. Isabell was not yet eight years old when she had to pass her first crucial horse test: Sabrina got scared right in front of the house for some reason and spooked. Isabell fell off and landed on the stairs, right on her face. She still has a small scar from the little stone that bored into her forehead. Her nose was torn, her lips burst open on the inside—she was taken to the hospital for stitches. In addition to the face wounds, she had a concussion. She had to spend a week in the hospital, eating and drinking with a feeding cup only. She told her dad furiously that she was done with riding, and that he could give Sabrina away. But one day later, remembers Heinrich, she changed her story completely.

“Listen, Dad,” she announced from her hospital bed, “I will teach her to listen to me.”

Ultimately, however, the gray mare was not allowed to stay. Sabrina was just too spooky for little girls.

Isabell and her sister Claudia grew into the German riding club lifestyle almost automatically, just what you would expect of social butterflies from the Rhineland. A large part of their youth was spent at Graf von Schmettow Eversael, the riding club not far from their farm.

We smoked our first cigarette behind the indoor arena. And we drank our first apple schnapps behind the embankment.

Three times a week, Claudia and I showed up for riding lessons with our ponies: twice for dressage lessons, once for jumping. On the weekend, we went on hacks with ten or fifteen kids, all with backpacks. We played games: skill games, gymkhana games, jousting, circus tricks. The horses had to wear hats, hearts, glitter, and glimmer—they were just as fancifully dressed up as we were. We chased across fields and swam with our horses in the river. I was always desperate during pony races because my pony, Funny, was smaller than Claudia’s (named Fee), and despite the utmost efforts on my part, I could not beat my sister. Funny was a 12-hand Welsh pony. Fee was half an inch taller and more wiry. In best-case scenarios, Funny made it to Fee’s tail during our races. But she was still awesome. Well-behaved, lazy, small, a little chubby. She did not like jumping at all, and I regularly came off, despite my persuasive powers (always once, sometimes even twice or three times in a lesson). It became my personal challenge to finish a jumping competition, just once, without falling off.

Despite the challenges of her pony, Isabell remained tough, and her mother managed to keep calm at the sight of her daughter being catapulted through the air. She only wondered where her daughter got the energy to climb back on the horse, again and again, after she had fallen off! Brigitte did not only drive her daughters to the riding club but also to their first horse shows, supporting their passion as best as she could. With their ponies, the sisters rode against other children on full-size horses.

Isabell’s father’s parents, with whom the family shared the house and who were still rooted in the traditional view of agricultural, were perhaps less supportive. Keeping horses for pleasure? Just for the children? Pointlessly driving the kids and ponies around when the time could be better used for work at home? Brigitte disregarded their objections, and the girls were allowed to ride. But, their resolute mother told them, “If you only want to ride for fun, we do not need to make all this effort. If you want to compete, then it needs to be serious. Then we will do it properly and it’s not just a game.”

From that minute on, the girls and their mother were on the road together every weekend. The question some ask, “Who instilled such ambition in Isabell?” has just become superfluous.

For her early schooling, Isabell studied at night, which is similar to what she would do later in life with her law studies, when she was already reaping international riding success. She always got away with it—although not necessarily with the best possible results. Her sister Claudia specialized in eventing, riding homebred horses, but did not want to devote herself “body and soul” to riding like her little sister did. Isabell rode everything she could get her hands on, no matter the discipline or the horse. Only when Dr. Uwe Schulten-Baumer, the most famous horseman in her neighborhood, took notice of her, did she specialize in dressage. She started riding his horses regularly at seventeen years old. He brought to the table his experience—a long life as a successful riding coach. She had the intuition and the courage. Both wanted to make it to the top. They complemented each other, eventually growing together as a team. They were a terribly successful duo! But Isabell did not only need her exceptional courage to handle the young horses and to take on the seemingly superior opponents in the dressage arena, she also needed it to stand up to Dr. Schulten-Baumer.

Isabell’s dad, who supported her vigorously during what were difficult years, said categorically when asked, “You don’t need to assess their relationship. It is enough if I do.”

Isabell’s family supported her when her partnership with Dr. Schulten-Baumer ended in 2001, after sixteen years. And Madeleine Winter-Schulze, who would become Isabell’s friend, patroness, and horse owner, came just at the right time. She bought several horses from Dr. Schulten-Baumer and invited Isabell to live and train at her and her husband’s facility in Mellendorf, Germany, close to Hanover. It was the perfect way out: it was a way forward into the future.

Dr. Schulten-Baumer paved the way for Isabell in the beginning; he helped her get her foot in the door of major sporting circles. He also taught her everything that she needed to school and train horses herself, and then lead them to success. Madeleine, her friend and sponsor, supported Isabell as she found a newfound freedom, buying horses for her. (Madeleine has Isabell’s back to this day.) Other riders often have to compromise and sell horses every now and then to keep their business profitable, but Madeleine ensures that Isabell can fall back on a solid financial footing. Both Madeleine and Dr. Schulten-Baumer came into Isabell’s life at the right time—it was almost magical, as if it was meant to be.

Talent alone is never enough; luck has to be added to the mix.

Isabell worked as a lawyer in a practice in Hamm, Germany, and also for the German department store chain Karstadt. This is where she met her future partner, former Karstadt CEO Wolfgang Urban.

He is my greatest support, the most important person by my side…he gives me direction, helps me in many situations with his experience, and is the one I can hold on to. He asks the right questions and shows me quite plainly where I sugarcoat or where I am kidding myself, even though he is not a horse or dressage expert.

Isabell’s life became divided, thematically and geographically with her work and her horses, as she covered thousands of miles on crowded German highways. From Rheinberg to Mellendorf, from Mellendorf to Hamm, from Hamm to Mellendorf, from there to a show in Munich, Stuttgart, or Neumünster. Things could not go on as they were. She had to make a choice. Isabell decided to leave both her jobs as a lawyer and as store manager, and to instead start her own business as a professional rider and trainer. So far, her professional life had been the background music to her true passion, a sideshow. Now she turned her passion into her profession.

After this came a night when Isabell became the “head” of her family. She was sitting on the couch at home with her father as they discussed the family farm and her own professional goals, and he said, “Maybe you can buy a facility somewhere close by. So many farms are vacant now, that could be an option.”

“Are you saying you don’t want me at home anymore?” Isabell asked.

Heinrich Werth did not say much in reply, only, “Thank you, Isabell. That’s enough.”

The next morning, Heinrich told his wife, “Let’s put our money where our mouths are. Let’s write the farm over to Isabell. I don’t want her to think that we don’t want her here.”

With that, the formalities were taken care of within a few weeks, and a fair solution was found for both Isabell and her sister, with clear conditions.

“When they ‘close the lid on me,’” said Heinrich Werth, “I don’t want them to have a falling out.”

Isabell took over the family farm. It became her residence in the fall of 2003, and her sister lives in her own home on the property. With the support of Madeleine Winter-Schulze, Isabell expanded the facility and built a new house for herself and her family. Every tree, every shrub that she can see has been planted during her lifetime. She also planted hawthorn hedges throughout the property to help structure the space. She is now in charge of a competition barn, a training facility, a small horse breeding venture that her father runs, and an agricultural business, which produces some of the feed for her herd. Forty to fifty horses are in training on the farm, from the three-year-old newcomers to the Grand Prix competitors. Together with the broodmares, the foals, the boarders, and a herd of retirees happily grazing in the field, the facility accommodates around a hundred horses. Fourteen employees take care of the horses’ well-being and their training. (Isabell very rarely accepts private students.) The veterinarian is on the grounds almost daily.

Technically, the business and the entire team revolve around one person and her system: Isabell. And she whirls around from morning till night.

Every morning, whenever Isabell is home, Brigitte—her mother—brings a glass of fresh-squeezed orange juice to the indoor arena. This is the opportunity for a quick exchange, regarding the farm.

Isabell asks from the saddle, “How are things going?”

If something is wrong or in question, mother and daughter discuss it over the arena wall. Nobody on the farm accepts long-lasting disagreements. Isabell left the belligerent part of her behind with Dr. Schulten-Baumer.

When you live in the country, you can always go to town every now and then. If you live in the city and wish to get out to the country, it is more difficult. I have my island here. Everyone needs an island, especially when you are away as much as I am. You learn to appreciate “home” even more.

Isabell and Wolfgang had a son, Frederik, in October 2009 when Isabell was forty years old. At the time, she had her life organized down to the most minute of details. She had a plan for every morning, and everything revolved around the horses. With a baby, it all changed. She had to learn to organize the horses around Frederik and make a drastic shift of importance in her mind from her four-legged family to her two-legged one.

Frederik was absolutely planned. He is my greatest joy, my greatest love, and he has expanded my horizon in the most meaningful way. Nothing else is really important, as long as Frederik is happy and healthy.

Often, Isabell feels bad because she is away from home so much, and Frederik developed an instinct early on to turn this to his advantage, seeking as much compensation from his mother as possible. Now, Isabell tries to choose competitions according to whether Frederik might enjoy them—for example, one with a petting zoo next to the showgrounds has a better chance of Isabell’s participation than one with lots of stress and obligations, where Isabell has to pose for selfies instead of being with her son.

In many ways, Frederik’s childhood has taken place on an idyllic island. His parents are intent on not turning him into a spoiled only child but instead teaching him the modest life of previous generations. The daily routine is due to careful decisions and planning. His world is more complicated and more organized than his mother’s was. He, too, is surrounded by animals, but he is not stuck on the farm. He has already been on a plane many times. And best of all, somebody is always there to take care of him—both of his parents are home with him almost every night.

When Frederik first came to the indoor arena, he always wanted to sit on my horse. Not on his cousin’s pony, which was immediately offered to him. No, he wanted up on his mom’s horse—not to ride, but to be close to me. This was often impossible because my horses were too wild. It bothered him, and he complained. To him, it felt as if the horses took away his mother.

Isabell’s parents no longer take long trips. In the past, they would gather a cheerful crew from the local riding club, get on the bus or plane, and accompany Isabell to her bigger competitions. This started at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona. The president of the local riding club arranged a bus for almost thirty people and a ski rack in the back for provisions (beer was obligatory). The cheering section from the Lower Rhine region crossed into France, laughing and chatting all the way to Spain, alcohol flowing freely. Each day, they trekked to the stadium as a boisterous fan club from their rental home in Barcelona. Four years later, at the Olympic Games in Atlanta, the loyal crew even got a house that was closer to the competition venue than the riders’ lodgings! The Isabell Fan Tour visited Rome, Lipica, Gothenburg, and Jerez de la Frontera, and Isabell’s parents made up for what they missed at home before, when responsibilities like animals needing to be fed and fields needing to be tended required the presence of their farmers.

Whenever Isabell returned home after a successful outing, a special celebration was in order. The riding club hosted glorious receptions, with more revelry and horses harnessed six-in-hand.

The Fan Tours only stopped traveling when, at the end of the World Equestrian Games in 2010, the president of the riding club suffered a heart attack. Fortunately, it did not have any serious consequences, and Isabell made sure he was safely transported home from Lexington, Kentucky, where the event was held—paramedics were waiting for him with a stretcher upon his arrival in Germany. The president of the club was part of her extended family, after all.

Today, the club structure has changed. Many of the younger generation of riders do not know Isabell personally. As a whole, the club life is no longer as central to the members as it once was.

And now Isabell’s father Heinrich only drives as far as his own fields. He grabs the dogs and his grandson Frederik and hops on his four-wheeler. The acreage that he used to plow is now his playground. Maybe, while zipping about, his thoughts wander back to the time when he was still working the land according to the old traditions…or perhaps even further back, to the era that even he only knows from stories.

Heinrich Werth’s grandfather bought the property in 1915. Industrialism dislodged him from his farm in Walsum, Germany, on the other side of the river Rhine. There was neither running water nor electricity on the farm—the well pump was operated manually. The family sat together at night by candlelight, but not for very long before their eyes started to close from fatigue. After all, they had to be up and running at four in the morning to milk.

“It’s true, people back then worked very, very hard,” muses Heinrich, “but they were not stressed.”

Maybe, as he’s driving around with his grandson, he remembers his childhood years, and the Second World War, when five of his uncles died on the battlefield and hungry townspeople came to the countryside to ask for food. The farm saw it all! American soldiers took up quarters there; you can even see bullet holes in the side of the main house, dating from this time.

But as Isabell’s mother Brigitte points out, setting her coffee cup down with emphasis, “We will be sitting here all night if we keep talking about the past!”