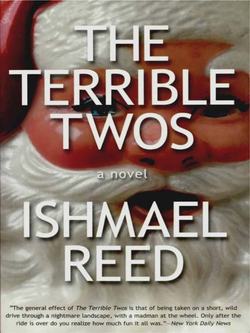

Читать книгу The Terrible Twos - Ishmael Reed - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

Оглавление“This parade ought to perk up the trade,” said the first boss, sipping a scotch and holding a cigar with a free hand. “Weather’s just right. Maybe the industry will top the six billion we made last year.”

“We’ll be lucky if we break even. Things look pretty bad to me. You heard about Korvettes, didn’t you? Out of business, interest rates too high. J.C. Penney’s phasing out some of its stores, too. It’s going to cost them fifteen million dollars to close them down,” the second boss said. “It’s all Carter’s fault. Him and the Federal Reserve.”

“Don’t blame it on Carter. Blame it on the Arabs.”

“The Arabs don’t have long. They’ll run out of oil in the late eighties and then we’ll have to bail them out. You see them in Paris, dancing with French girls and in London spending cash on every frivolous thing. I heard that one of them wanted to buy the Alamo, in San Antonio, Texas.”

“The Alamo? Why would he want to buy the Alamo?” A huge replica of Kermit the Frog floated by.

“Because his son went to school near there, and was impressed with the legend of the Alamo.” A group of clowns holding balloons walked by.

“We’re taking a beating on those quilt down coats. The women say they can’t move comfortably into their station wagons wearing those coats.”

“Yeah, but the toys are selling well. Especially the computer games. There’s also a rush on microwave ovens.”

“If American labor made better stuff we could sell it. If it isn’t sick leave they cost us money by carrying home the goods. They have no loyalty to us any more. That’s why the Japs are ahead of us. Did you see that little Jap sucker on TV the other night? He said that America can’t be good at everything all the time and that we must allow some nations to be at least pretty good at some things. I felt like pushing my fist right through the TV and mashing in that little Jap’s face. Boy, was he rubbing it in. Reagan will take care of them. The Japs and Iranians, the blacks and all the rest.”

“A fine fellow. He has a closet full of Levi Strauss jeans. They got him on the cover of Hour-Glass magazine in a blue denim shirt. He’ll help the industry. He’s a sharp dresser and well-groomed. Every sixteen days he gets a haircut.”

“That issue of Hour-Glass isn’t even out. How did you know all of that?”

“There’s this kid down in hardware. His name is Oswald Zumwalt. He has some great ideas. His wife is a copy editor at Hour-Glass. She gets advance copies. He’s always bringing me copies of Hour-Glass before it reaches the stands. I like the kid. He’s very ambitious. He’s inviting me over for dinner, later this afternoon. You know, since Grace died, I haven’t gone out so much. It’s nice to have someone make dinner for you. Anyway, Zumwalt says that we could cut costs if the whole industry got behind one Santa Claus and made this Santa Claus available only to those who could pay. We would charge people admission to come into the stores and have their kids consult Santa Claus. He said that Santa Claus is too dispersed as it is. Zumwalt’s very smart. Hyperkinetic, but smart. He says we could cut down on labor costs by doing what the Japanese do.”

“What do the Japs do?”

“Hire robots. He says that in Japan the robots work alongside humans so that the humans have to work harder to keep up. He says that they already have robots who can take over from the models.”

“The women would never go for that. They want flesh and blood, ass and tits.”

“They can create women. You ever see that film, The Stepford Wives? Well, in this film there’s this mad professor in a New England town who is turning all of these women into robots. All of them pushing shopping carts, smiling, behaving themselves. You couldn’t tell the difference.”

“I see what you mean, Herman.” Cinderella in a low-cleavaged gown danced on a float with her Prince Charming. The float was shaped like a castle. The two men stared.

“Maybe you ought to give this Zumwalt kid a promotion. See what he’s got. Rare to find a kid who’s ambitious these days. I think Reagan’s going to bring back the sixties. I don’t want to go through that again. Cities burned. Insurance rates shooting sky high.”

“He cooks, too. He’s cooking dinner today.”

“What’s the matter with him?”

“Plenty of fellows do that these days. Cook, babysit.”

“How’s your son doing?”

“He’s still in the seminary. I got a card from him. It was covered with strange-looking stamps.”

“Yeah, what did he have to say?”

“He said he was having some kind of dispute with his superiors. He said they were too devoted to orthodoxy and ritual. He claims that he’s a part of a new church. A church devoted to social and political issues. His position was the source of his troubles.”

“That’s a mouthful. My nephew always did have a head on his shoulders.”

“There’s something that worries me, though, George.”

“What’s that, Herman?”

“When he came home for the holidays he brought this strange man with him called Brother Andrew. This Andrew kept addressing my kid as Bishop. He kept referring to him as the Bishop this and the Bishop that. He wouldn’t call my kid by his right name. My son ain’t no Bishop. I’m wondering what the hell is going on.” A float passes by carrying Dean Clift, the top male model of the United States. He is modeling some snug-fitting jeans. Men and women struggle with the police. They want to touch him, to feel him. There are a few anxious moments as they almost turn the float over.

Look at them. They’d cut out my heart if I’d let them. Take parts of it home as souvenirs. I have dreams of their fanglike eyes staring at me. My public. My audience. My life. When I’m in bed at night I see hands reaching through the walls, trying to get me. Will they always crave this body? This body which has never shown an inch of flab. It’s becoming more difficult to keep this body in shape. Maybe I should think of a new career. Sometimes I can’t distinguish between the real me and the billboard me. My life’s story seems to be a series of billboards, television commercials, beer ads, cigarette ads, shirt ads. I live between the covers of magazines like the commercial Buster Brown who lived in a shoe.

The crowd surges once again to get their grips on Mr. Dean Clift. The whole country wanted to cling to him, to become treacly over him. It had been a pretty easy life except for the tragedy occurring a few years before, and now there were muscle spasms, and palpitations, backaches, and sometimes on cold mornings he couldn’t move his index finger.

Soon I will look like Santa Claus, and what then? If Elizabeth hadn’t made those wise investments there would be no future for me at all. She manages the house on the Hudson and the apartment in New York. But what good is it? The city is overflowing with bag people, trash people, beggars of all kinds, refugees. Maybe I should accept those politicians’ offers. Run for Congress from the silk stocking district. Looks easy being a congressman. “You don’t even have to show up for work half the time. You meet interesting people and get to travel a lot. Something to think about.

They have to speed up Dean Clift’s float. Some of the crowd has pushed through the barricade and have to be clubbed by the police.

“Handsome fellow, huh, George? He looks like Steve Canyon. That set square jaw and those comic-book blue eyes.”

“He isn’t queer, is he?” asked Herman.

“Naw. He’s married and he’s got two kids. Well, one kid now. A girl. The oldest kid was killed in a bizarre accident at Harvard. He was trying to hoist a Confederate flag over his fraternity house and this other kid, a campus radical, started wrestling with him and the kid fell. He was impaled on a spike and was carried off wriggling on that spike. They had to cut off part of the fence to take him away to the hospital. He was dead on arrival. The kid that did it got away. He dropped out of sight.”

“How awful. Did you hear the news?”

“No, what news?”

“They’re thinking about running Clift for Congress from the silk stocking district.”

“What?”

“But he doesn’t know anything about anything. I’ve never heard him express a thought. At the parties, he’s always smiling at you, flashbulbs popping, beautiful women on each arm, the hostesses outdoing themselves to see that he gets what he wants.”

“Yeah, but he’s not just a jock. He does more than lift weights. He’s the highest-paid model in the United States. His face is everywhere. He gets as much as twenty thousand an hour. If a man like that had a brain he’d be dangerous. He’s got his wife managing his investments, according to an interview I read in Women’s Wear Daily. Calls her Mommy. Mommy this, Mommy that. Totally dependent on her. She packs his clothes and draws his bath water. A shrewd woman, though. Besides, who knows, they may become so cautious they won’t even want an actor fronting for them. He may pull a Mr. Smith on them.”

“What do you mean?”

“That movie. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. In this one scene, Mr. Smith gets up and makes a speech in Congress in which he exposes all of the corruption in the land, and this one Senator, played by Claude Rains, becomes so agitated he leaps to his feet and confesses it all. I have a cousin who puts it this way: a dancer’s greatest fear is losing his legs, a painter’s his vision; an actor sometimes forgets where the real him ends and the character takes over. Writers too. You know, this guy Simenon, he said he quit writing because his characters began to dominate him, tell him what to do. So just like in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the actor may tear up the script, ignore the teleprompter, and really say what’s on his mind. They might decide to replace him with a robot.”

“Aw, George, things will never get that bad.”

“Don’t count on it. A university in Santa Monica is working on a doll that will be so real it will be macabre. They plan to have it on the market by Christmas ’eighty-four.”

The men chuckle. “What do you say we go over to the club for a drink? I’m tired of the parade.”

“I can only stay for one martini. I have to fly to Texas tomorrow. Are they going to be sore when they see the bad sales figures.”

“Yeah, it must be tough on you, Herman. Arguing before those Texans. These slumps occur, but business ought to pick up. You’d think they’d give us more time.”

“What do they know about time? All they know is money and filthy bathroom humor.”

“We should have never sold Rehab Oil those shares. They know absolutely nothing about the department store business. Our grandfather comes over here from Germany. Builds the store from a pushcart peddling pots and pans. And then we modernize it and bring it into the twentieth century with high class merchandise, but how could we compete with these big merchandise chains and their discounts and their computers and space-age marketing techniques?”

“Maybe we’re done for, George. Maybe they’ll get rid of us and bring in some younger blood, some anonymous clean-shaven face who’ll do their bidding. The East is dying. We’re dying. Everything is shifting to the West. The sunbelt, and the gold coast of California. The Japs have bought up about three states in the West.”

“The East will never die. The East will suffer some setbacks, but it won’t die. Too much sun out there. Genius thrives in bad weather.”

The first boss signaled the driver. The huge fossil-fuels monster turned from the parade barricades and slowly headed towards the East Side. As it moved away, Sister Sledge rode by on a float shaped like a huge turkey.

Vixen, standing near the curb, knew about Sister Sledge. She remembered their song, “We Are Family,” the theme song of the Pittsburgh Pirates. “We Are Family.” It never occurred to her that it was sung in march time. She wished she and her husband, Sam, were a family. They were drifting apart. During the holidays, she began to yearn for the old values. Of home and hearth. Maybe it was her New England background. The white steeples, the cemeteries, and the fir trees of New Hampshire and the white birch of Vermont. She’d cooked a Thanksgiving feast for herself and Sam. Turkey, corn, pumpkin pie. That’s how much the holidays got to her. She would always get the blues during the holidays. But Sam hadn’t come home. He had said he was going down to one of the East Side piers to hear a jazz concert, but he hadn’t returned. Maybe there was another woman. She caught him once with another woman and he said that he had to do it because the creative drive is connected to the libido and that he had a painter’s block. She wondered was he fucking that dark-haired slinky-looking waitress down on Prince Street. She wondered if he knew she was fucking Romeo, his best friend. Unlike Sam, who sometimes made her feel like a human doughnut, Romeo took his time. He looked like Julius LaRosa and did it elegant like Marcello Mastroianni.

This marriage was the pits. She was tired of the painters coming over to her house, smoking pot and drinking beer and referring to painters who weren’t present as prostitutes and faggots. She wanted to have Sam’s baby but he’d smoked so much dope that his sperm, instead of containing the population of a small town, held that of a bus stop in Oakland. Plus, he had a chronic cough now. She’d read that marijuana contained some kind of fungus similar to that one finds in the damp dark corners of a house. She was tired of working as a busgirl and ticket taker while he painted. She was better educated than his friends were and if they’d listen to her she could tell them why nobody would give them a show. The stuff they were heralding as new was done thirty years ago in Belgium. She was tired of New York. She didn’t have any girlfriends she could relate to. New York was grimy and the sky always had the color of an embalmed oyster. In her elevator, they’d found a woman who had been brutally raped and murdered; she had been stabbed thirty-two times. Drunks urinated at the entrance to their loft. They were three months behind in their rent because Sam had quit his shipping-clerk job in order to, as he put it, devote full time to his “art.” He was in bad shape. He wouldn’t even clean underneath his nails. He was always scratching his scalp. He gave her the crabs, and his belly was beginning to drop over his belt, and all he did was lie around or talk a lot of feverish incoherent meaningless jargon full of “O Wow.” He used to say “heavy” a lot but he met a French painter at a party and now he was saying formidable a lot. She was having fun today watching the Macy’s parade.

The parade looked like an illustration by a well-known American illustrator who smoked a pipe and owned a prominent Adam’s apple. Melba Moore sang atop a float sponsored by the Daily News. It was made of a miniature skyline of New York dominated by a huge apple. Melba sat on the apple singing “I Love New York.”

Sam’s friends would ridicule Vixen for taking delight in this Thanksgiving Day Parade. She was wearing the same black bear coat she’d worn in college. She had blown hair. Her hands were shoved into her pockets. She had a feeling of well-being because she was close to a decision. She always had this feeling when her mind was being made up and she was about to take another step. She’d been dreaming of her father recently. He’d died of a heart attack a few years ago. Her mother was smart and glamorous and didn’t have much time to be a mother. She’d run away to New Mexico and, when last heard, she was drinking herself to death.

Her friend Jennifer had moved to Alaska. Jennifer had written that there were lots of jobs and men available in Alaska. A poet, Ed Dorn, had said that Alaska reminded him of Raquel Welch. She wondered what he meant by that. Perhaps one day she would find out.

The Rockettes marched by. They towed a swan-shaped sleigh whose passenger was none other than Santa Claus himself. He was waving and wishing everybody a Happy Thanksgiving and a Merry Christmas.